Journal of

eISSN: 2377-4312

Research Article Volume 3 Issue 1

1Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Mansoura University, Egypt

2Department of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Mansoura University, Egypt

3Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Mohamed Zakaria Sayed-Ahmed, Department of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Mansoura University, Mansoura, 35516, Egypt, Tel 00966 594 886878, Fax 00966 17 3216837

Received: January 20, 2016 | Published: February 4, 2016

Citation: Shoieb SM, Sayed-Ahmed M. Clinical and clinicopathological findings of arthritic camel calf associated with Mycoplasma infection(Camelus dromedarius). J Dairy Vet Anim Res. 2016;3(1):26-30. DOI: 10.15406/jdvar.2016.03.00068

Objective: The present study aimed to investigate the clinical and clinicopathological findings of arthritic camel calf associated with mycoplasma infection in district areas of Saudi Arabia.

Methods: Fourty-one camel calves from different farms with different sex and age from 1-12months were used in this study. Thirteen camels did not have any clinical articular abnormalities while twenty eight camels had gross articular problems such as lameness and swollen in joints either monoarthritis or polyarthritis. The synovial fluid was extracted from the arthritic joints. Then, the concentration of TLC, RBCs, and TP were measured in samples. The mycoplasmaisolates which were identified were further confirmed by disk growth inhibition test using a panel of specific antisera against selected reference mycoplasma spp.

Results: Concentration of all measured parameters in arthritic joints were significantly higher than clinically healthy joints (p<0.05). The synovial fluid concentration of TLC, RBCs, and TP were 9525±526cells/µl, 4804.4±91cells/µl, and 2.820±104g/dl in arthritic joints respectively. The most commonly isolated bacteria were Mycoplasma spp., followed by non-haemolytic streptococci spp. and Staphylococcus aureus.

Conclusion: This study gives us a spotlight on the significance of mycoplasmaarthritis in camel calves and significant increase of acute phase proteins and inflammatory cells in the synovial fluid. Information about the normal values of these parameters and their changing patterns may help camel rearing systems during arthritis by assessing the health status of joints in the camels; in addition, the information about normal values can be diagnostically valuable when considering diseased animals.

Keywords: camel calf, arthritic joints, mycoplasma spp, synovial fluid, clinical study

TLC, total leukocytic count; RBCs, red blood cells; TP, total protein; M. Bovis, Mycoplasma bovis; WBC,white blood cell; TNCC, total nucleated cell count; SD, standard deviation; FPT, failure of passive transfer; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase

Camel is an economically important farm animal used for meat, milk and hair production in the Middle-East and North Africa.1 Mycoplasmas are highly contagious organism capable of auto-replication and difficult to culture and slow growing.2,3 Camel joints are infected by variety of infectious diseases that may affect their racing performance. Mycoplasma spp. are considered the common causes of some diseases as arthritis, pneumonia and abortion.4 Camel calves are more susceptible to mycoplasma infection and developing clinical signs.5 Consequently, the pathogen cannot be detected during the incubation period. Moreover, the serological cross reactions among the Mycoplasma spp. are a critical problem.6,7 Synovial fluids analysis is the common method for diagnosis of various joint diseases.8 The most commonly isolated organisms are Staphylococcus spp., Escherichia coli, Arcanobacterium spp., Corynebacterium and less commonly Mycoplasma spp.8 Navel ill is considered the most common term which includes navel abscesses and umbilical hernia.9‒11 Reports on arthritis associated with mycoplasmosis in camels are scare. Consequently, the present study aimed to assess the clinical and clinicopathological findings associated with arthritis caused by Mycoplasma spp. in camel calves in district areas in Saudi Arabia.

Study area

The present study was conducted in Four areas in central province in Saudi Arabia including (Shaqra, Hermla, Dorm and Al-Qassim region) which are rich in camel population. Each area had been visited two times per month to collect the samples (synovial fluid, blood and serum) from affected camel calves.

Animals

A total of 41 camel calves at 1-12months of age from different farms were clinically examined for presence of arthritis. The morbidity and mortality rates of the disease were identified from camel owners in the areas of study. All the clinical data were collected from the camel’s owners in the areas of this study.

Clinical examination

Competent clinical examination of each camel was done consistent with Radostitis et al.12 Data concerned with the case history, clinical findings for each camel under investigation were recorded.12 A detailed clinical examination of the diseased camels, including examination of joints was carried out.

Synovial fluid collection

Five milliliters of synovial fluid were collected from each joint using a sterile syringe after joints anesthetized, clipped and scrubbed using povidone-iodine solution. The needle was inserted into the medial pouch of the joint. Only blood-free samples were included in the analysis. In cases that blood contamination was suspected based on visual examination, the sample was discarded and a second sampling was attempted at a remote site in the joint. The collected synovial fluid was placed in anticoagulant-coated tubes and stored at -20°C until use. Al-Rukibat et al.8

Synovial fluid analysis

The color, viscosity, presence of floccules and degree of turbidity of aspirated fluid were noted immediately after collection. One direct smear was taken on glass slides and another smear was prepared from resuspended sediment. Slides were stained with Wright’s stain and examined for cell morphology, differential leucocytic count (DLC) and Total nucleated cell counts (TNCCs) using a haemocytometer (L.W. Scientific Inc., Tucker, GA, USA). Total protein (TP) was analyzed using a regular refractometer (Caesar Instrument Co., Taipei, Taiwan).

Serum analysis

Blood was withdrawn from the jugular vein, centrifuged for serum separation and stored at -20°C until use. Glucose, cholesterol, AST and LDH were determined by their commercial reagents in an autoanalyzer (Alcyon 300/300i, Abbott). Serum proteins were determined by using 7.5% acrylamide gel (Laemmli UK, 1970, HSI, 1993).

Isolation of Mycoplasma

Few drops of synovial fluid were inoculated into PPLO broth then incubated at 37°C for 24hour; the incubated broth were platted on PPLO agar plates in humidified candle jar with low oxygen tension. The Mycoplasma colonies were examined after 48hours then daily up to 7-10days for fried egg colonies.13

Gross examination of joints

The affected joints were examined for pathological lesions such as thickening of the joint capsule, abnormalities in the synovial membrane and other cartilage deformities.

Bacterial culture

Few drops of synovial fluid were inoculated into colombia blood agar base (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) enriched with 5% defibrinated sheep blood then cultured on MacConkey agar plates (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland). The inoculated plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 hours. Growing colonies were picked up, inoculated on nutrient broth and then subcultured on tryptic soy agar (Difco). The bacterial isolates were classified by species according to Barrow & Feltham14 and Quinn et al.15 Samples not showing any bacterial growth after incubation were 10-fold diluted (10-1 to 10-6) in deionized water 10% (v/v) and cultured in agar and broth Mycoplasma experience media (Reigate, Surrey, UK) using a standard procedure.3 Broths were examined daily and for 1week for signs of growth opalescence or changes of pH indicated by a color change in the media. Plates were also examined for 7days under 35X magnifications for typical fried egg appearance.

Statistical analysis

SPSS software (SPSS for Windows, version 11.5, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois) were used for data analyses. The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Physical examination

41 camel calves with arthritic joints varies from lameness with or without swelling of the joints, the swollen joint either single or multiple swollen joints. Camel calves were lame for a variable period of time. The age of these camel calves was 1-12 months. Lameness was graded on five scales. Scale 1 (normal gait) and scale 5 (severe lameness with arched back) according to Spercher et al.16 The joint swelling was assessed as mild, moderate and severe. Fetlock joint considered the most frequently affected joints (6 animals; 21.4 %), the carpal joint (4 animals; 14.2%), the tarsal joint (3 animals; 10.7%), the elbow joint (3 animals; 10.7%), the stifle (3 animals; 10.7%), the fetlock and carpal (3 animals; 10.7%), fetlock and tarsal (2 animals; 7.4%), and elbow and carpal (4 animals; 14.2%) (Table 2). The mycoplasma arthritis showed polyarthritis or monoarthritis with respiratory signs and lameness (Table 1). The affected joints were mildly to moderately swollen and painful to manipulation. Most of polyarthritis involved wound in joints may be fistulated and oozing some pus. The affected camel calves were feverish, anorexic, runny eye and in some cases were recumbent.

Clinical Finding |

Mycoplasma positive (n= 28) |

Mycoplasma negative (n= 13) |

||

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

|

Anorexic Calves |

25 |

89.2 |

8 |

61.5 |

Fever |

19 |

67.8 |

6 |

46.1 |

Depressed Calves |

18 |

64.2 |

5 |

38.4 |

Cough |

19 |

67.8 |

4 |

30.7 |

Runny Eye |

12 |

42.8 |

2 |

15.3 |

Watery Nose |

18 |

64.2 |

6 |

46.1 |

Monoarthritis |

19 |

67.8 |

2 |

0.15 |

Polyarthritis |

9 |

32.1 |

2 |

0.15 |

Lameness without Swelling in Joints |

0 |

0 |

9 |

69.2 |

Recumbency |

17 |

60.7 |

7 |

53.8 |

Wounds involved in the Joint |

23 |

82.1 |

1 |

0.7 |

Table 1 The clinical finding associated with isolated mycoplasma in camel calf

Joints examination

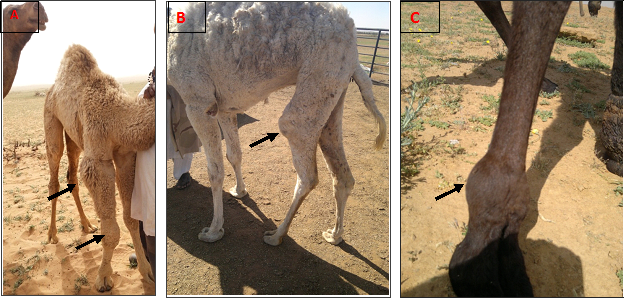

There was mild eburnation of the articular cartilage in 28 joints. The examined joints were inflamed, edematous with thickening of the synovial membrane. The thickening of joint capsule was observed in 12 joints. The most frequent affected joints were elbow and carpal in polyarthritis and fetlock and carpal in monoarthritis (Table 2 & Figure 1).

Signs |

Monoarthritis |

Polyarthritis |

Total |

||||||

Fetlock |

Carpal |

Tarsal |

Elbow |

Stifle |

Fetlock and Carbal |

Fetlock and Tarsal |

Elbow and Carbal |

||

No of animals |

6 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

28 |

Percentages |

21.40% |

14.20% |

10.70% |

10.70% |

10.70% |

10.70% |

7.40% |

14.20% |

100% |

Table 2 The sites of joints affection associated with mycoplasma infection in arthritic joints in camel calves

Synovial fluid analysis

The macroscopic findings of collected synovial fluid showed turbidity, blood with occasional floccules. Concentration of synovial fluid parameters in arthritic joints was significantly higher than normal range (p<0.05). The TNCC and TP concentrations are presented in Table 3. Observation of altered ALT and LDH and rise in serum TP levels were interpreted as infection. In diseased animals glucose and total cholesterol values were low (p<0.05) and urea were high (p<0.05). Differences among ALT, creatinine, total protein, albumin were statistically not significant (Table 5).

Bacterial culture

Bacterial culture revealed seven isolates for mycoplasma. In four samples, no bacterial growth was observed as showed in Table 4.

TLC |

Neutrophils |

Lymphocytes |

Mono/Macrophages |

Red blood cell (cells/µl) |

Total protein (g/dl) |

9525±526 |

5472±396 |

1804±1008 |

1896±109 |

804.4±91 |

2.820±1.4 |

Table 3 Synovial fluid analysis of arthritic joints in camel calves

Isolates |

No. of samples |

Mycoplasma Spp. |

28 |

Staphylococcus aureus |

1 |

Non-haemolytic streptococci |

3 |

No growth |

9 |

Table 4 Bacterial species isolated from arthritic joints of young camels (n=41)

Parameters |

Mycoplasma Negative |

Mycoplasma Positive |

Glucose (mg/dL) |

65.00±21.66 |

35.00±01.6 |

Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

108.55±11.98 |

67.33±4.61 |

Albumin (g/dL) |

39.57±0.12 |

36.2±0.12 |

Creatinine (mg/dL) |

1.47±0.1 |

1.45±0.41 |

Total Protein (g/dL) |

5.74±1.92 |

5.52±1.63 |

Urea (mg/dL) |

6.58±0.38 |

22.38±0.2 |

AST (U/L) |

78.16±1.3 |

105.7±2.2 |

ALT (U/L) |

12.53±1.79 |

13.8±1.98 |

Table 5 The average values and statistical significances of sera biochemical parameters between calves positive mycoplasma versus negative calves

Infectious arthritis is considered the common cause of lameness in different animal species including camels. It caused edematous swelling of joints, thickening of the synovial membranes and changes in synovial fluid components. The joints in calves are mainly infected during bacteremia from a remote nidus of infection.17 In the current study, the affected camel calves with Mycoplasma arthritis had monoarthritis and polyarthris. The fetlock joint was the most commonly affected joint, followed by the carpal in monoarthritis and elbow and carpal in polyarthritis.18,19 Many of the diseased animals have swellings at the joints (monoarthritis/polyarthritis) which restrict the animal movements and causing respiratory manifestations.20,16 The cytological and biochemical characteristics of synovial fluid in joints of healthy camel calves have been recently published.8,21 The differential leucocyte count, TLC and red blood cell counts in synovial fluid of arthritic joints were apparently higher than normal range (Table 3). This is because of the variation in the degree of inflammation in various joints. In healthy camel calves, the TNCC, polymorphonuclear and mononuclear leucocytes in the fetlock and tarsal joints were <500 cells/µl and 400 cells/µl respectively.8,21 In inflamed joints, large molecules such as protein were increased in the synovial fluids due to increases vascular permeability which allowing influx of these molecules in the synovial fluid.17 Total protein (TP) concentration in cattle with septic arthritis was found to be >4g/dl.15 Similarly, TP in affected joints of camels were increased, but to a lesser degree compared with that in cattle. In healthy young camels, TP concentration in the arthritic joints was reported to be 2.8±1.4g/dl.8,21 The concentrations of TP in affected joints were depending on the degree of inflammation of synovial membrane and on the cause of the condition.22,23

Bacterial culture is one of the most important clinical tools in the diagnosis of infectious arthritis. The limitation of the usefulness of routine synovial fluid culture is due to localization of bacteria in the synovial membrane, previous antibacterial administration and the inherited antibacterial properties of the synovial fluid.24,25

In conclusion, this study gives us a spotlight on the significance of Mycoplasmaarthritis on camel calves and significant increase of acute phase proteins and inflammatory cells in the synovial fluid. Information about the normal values of these parameters and their changing patterns may help camel rearing systems during arthritis by assessing the health status of joints in the camels; in addition, the information about normal values can be diagnostically valuable when considering diseased animals.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2016 Shoieb, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.