Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4345

Case Report Volume 5 Issue 6

1Department of Diagnostic Science, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, USA

2Diplomate in the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, USA

3Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, School of Dental Medicine, East Carolina University, USA

Correspondence: Richard J Vargo, Department of Diagnostic Science, School of Dental Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, 3501 Terrace St, Pittsburgh, PA 15261, USA

Received: November 02, 2016 | Published: December 29, 2016

Citation: Vargo RJ, Bilodeau E, Jaradat JM, et al. A nonhealing periapical radiolucency. J Dent Health Oral Disord Ther. 2016;5(6):365-368. DOI: 10.15406/jdhodt.2016.05.00177

Background: This case discusses a radiolucent lesion in the anterior mandible, which initially was thought to be due to endodontic failure. However, the final diagnosis was xanthogranuloma.

Case description: We have reported a case of xanthogranuloma in the mandible found at the apices of two endodontically treated teeth. When present in the oral cavity, it can appear similar to several more common entities. While the radiolucent periapical lesion was thought to be the result of non-healing root canal therapy, the excisional biopsy yielded the diagnosis of xanthogranuloma. Removal of the lesion has resulted in excellent healing, as the surgeon expected.

Practical implications: This case demonstrates the importance of biopsy in definitive diagnosis of oral lesions and lesions found at the apices of previously endodontically treated teeth.

Keywords: periapical radiolucency, xanthogranuloma, excisional biopsy, endodontics

Xanthogranulomas are a non-Langerhans cell histiocytotic lesion most commonly seen on the skin of infants and children.1 Lesions in adults can occur; and, rarely, xanthogranulomas present in the oral cavity.1,2 While the etiology is unknown, this entity is thought to be reactive.2 Histopathologically, xanthogranulomas show a dense infiltrate of histiocytes.3 The lesions also have a variable number of Touton giant cells and principally perivascular and perilesional inflammatory cells.3,4 Immuno histochemically, the lesion is positive for CD68, factor XIIIa, fascin, and alpha-antitrypsin and negative for S-100, CD1a, beta-actin, and desmin.1 Most cases of cutaneous xanthogranuloma do not require treatment and have a favorable prognosis because the lesions spontaneously regress.1‒5 However, spontaneous regression has only been reported in the case of one oral lesion 2. If the lesion does not regress, treatment usually consists of surgical excision.2 Herein, we report a case of xanthogranuloma in the mandible found at the apices of two endodontically treated teeth. One other very rare diagnostic possibility that should be considered is a periapical granuloma with Touton-like giant cells. When present in the oral cavity, xanthogranulomas can appear similar to several more common entities.2‒6 Therefore, this case demonstrates the importance of biopsy in definitive diagnosis of oral lesions and lesions found at the apices of previously endodontically treated teeth.

Clinical and radiographic presentation

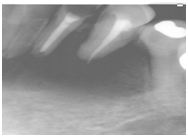

A 62-year-old female was referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon at the University of Pittsburgh School of Dental Medicine from her general dentist for evaluation and treatment of a periapical lesion in the anterior left mandible. The medical history was reviewed, and it was significant for mild von Willebrand disease, iron deficiency anemia, depression, and neurofibromatosis type 1. Regarding the referral, no information was given as to the history of the previously endodontically treated mandibular left canine and left lateral incisor and no previous radiographs were available from the outside general dentist. Due to the lesion’s location adjacent to endodontically treated teeth, an endodontics consult was obtained. Cold testing, percussion, and palpation were completed. Both the mandibular left canine and left lateral incisor were found to have no pain to percussion, no pain to palpation, and no response to cold. The probing depths were less than 3mm. Radiographically, a 2.0cm unilocular, well-defined, non-corticated radiolucency that extended from the mesial of the left mandibular second premolar to possibly the distal of the left mandibular central incisor and also interproximally to the crest of the alveolar bone was seen (Figure 1). Thin crestal bone was still noted interproximally, and the associated teeth had the appearance of floating in the air. There was loss of lamina dura surrounding the left mandibular canine, lateral incisor, and central incisor with root resorption. The left mandibular canine appeared to show very thin root walls, root resorption, and poor seal of the apex. The pulpal diagnosis for both teeth was previously treated, and the periapical diagnosis for both was asymptomatic apical periodontitis. Due to its guarded prognosis, the proposed treatment involved the extraction of the left mandibular lateral incisor. No treatment was recommended for the left mandibular canine due to its favorable post-surgery prognosis. The oral and maxillofacial surgeon performed an excisional biopsy of the lesion, and the cystectomy specimen was submitted in formalin for histopathologic examination.

Figure 1 The periapical radiolucency extends from the mesial of the left mandibular second premolar to possibly the distal of the left mandibular central incisor and also interproximally to the crest of the alveolar bone. Thin crestal bone was still noted interproximally. The associated teeth had an appearance of floating in the air.

Differential diagnosis

The patient presented with a radiolucency located near two previously endodontically treated teeth in the anterior mandible. In forming a differential diagnosis, we considered entities that present with a similar radiographic and clinical appearance. Our main differential diagnostic considerations based on the clinical and radiographic findings were periapical granuloma and periapical cyst. Other diagnostic considerations included central giant cell granuloma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and metastatic carcinoma. To arrive at the final diagnosis, histopathology and immunohistochemistry were used to rule out these lesions. The final diagnosis of xanthogranuloma was not initially considered in the differential due to its rarity in the oral cavity. Our differential diagnosis for the apical radiolucency included periapical granuloma. When looking at the radiograph of our case, a poor apical seal can be seen on the left mandibular canine. Poor apical seal can result in a chronic inflammatory reaction at the apex, which could ultimately cause the root canal therapy to fail.7 Additionally, both the left mandibular canine and left mandibular lateral incisor appear to have poor coronal seal, another factor in potential failure.7 Periapical granulomas are found at the apex of a nonvital tooth.8 Histopathologically, the lesion shows inflamed granulation tissue but not true granulomatous inflammation.8 Clinically, most periapical granulomas are asymptomatic. Periapical granulomas can range in size from small, barely observable radiolucencies to greater than 2 cm in diameter.8 The radiolucency may be circumscribed or ill-defined, may or may not have a radiopaque corticated rim, and root resorption may occur 8. As stated, the lesion in our case was 2.0cm in diameter. When the radiographic area is greater than 200 mm2, the prevalence of periapical cyst to periapical granuloma is 92-100%.9 The radiographic size suggested against periapical granuloma, and the histopathological findings in the biopsy ruled out this entity. However, it is very difficult if not impossible to tell the difference between periapical cyst and periapical granuloma radiographically.10 Neither the radiographic size-when less than 200 m2-nor the presence of associated radiopaque lamina dura alone has been found to be sufficient to determine the type of lesion.11 As with the periapical granuloma, root resorption is common.8 Therefore, histologic examination is required to differentiate between these entities. Periapical cysts arise from epithelial remnants or rests that persist in the apical region following tooth development.8 Like periapical granulomas, these lesions are usually asymptomatic.8 Histopathologically, the cyst, which has a lumen containing fluid, is lined by stratified squamous epithelium, has a connective tissue wall, inflammatory infiltrate, and cholesterol clefts.8 Mucous cells and Rushton bodies may also be seen.8 While the radiographic appearance of the lesion suggested the possibility of a periapical cyst, the histopathologic examination in this case ruled this out. Central giant cell granuloma is a rarely aggressive idiopathic benign intraosseous lesion that occurs almost exclusively in the jaws.12 Central giant cell granuloma usually occurs in women under thirty, and 60% occur in individuals under twenty.10‒12 Radiographically, these lesions can be either unilocular or multilocular radiolucencies.8 When occurring in the first two decades of life, the lesion is usually found anterior to the first molar in the mandible, but in older individuals the lesion occurs more often in the posterior jaw.10 Clinicians can confuse small unilocular central giant cell granulomas with periapical granulomas and cysts if found at the apex of a tooth, so the radiographic appearance is not diagnostic.8 Clinically, the most common presenting sign is painless swelling, and the overlying mucosa may appear purplish in color.10 This osteolytic lesion histologically consists of osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells-different from the Touton giant cells seen in xanthogranulomas-a proliferation of fibrous tissue, proliferating mesenchymal cells, red blood cell extravasation, hemosiderin deposits, and reactive bone formation.8‒12 The radiographic location of the lesion made this diagnosis unlikely, and the histopathologic presentation ruled out central giant cell granuloma. Eosinophilic granuloma of bone is part of the spectrum of Langerhans cell histiocytosis without visceral involvement.8 Langerhans cell histiocytosis can appear similar radiographically to a periapical cyst, among other lesions.13 While possessing a variable radiographic appearance, the “teeth floating in the air” appearance is one of the characteristics of this lesion. Histopathologically, the lesion shows histiocyte-like cells surrounded by eosinophils.8 The Langerhans cells-with their histiocyte-like appearance-cannot be detected without special stains.8 Immunohistochemically, the lesion stains positive for S-100, CD1a, and Langerin, and negative for CD68.3 This staining pattern is the opposite of our lesion, the xanthogranuloma. Electron microscopy demonstrating Birbeck Granules would confirm the presence of Langerhans cells, further solidifying the diagnosis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis.8 While the appearance of the class I and class II histiocytic disorders may be very similar, the prognosis is worse for Langerhans cell histiocytosis.14 Because histology and immunohistochemical findings were not consistent with this diagnosis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis was ruled out of the final diagnosis. Malignancies involving the bones are more commonly metastases rather than primary tumors, and this remains true for bone malignancies involving the skull and jaws.15 The bones involved are most commonly the vertebrae, ribs, pelvis, and skull.16 The jawbones, however, remain a rare site for distant metastatic carcinomas.15 Metastatic carcinomas to the oral cavity-both to soft tissue and hard tissue-are uncommon, and they comprise only 1-3% of malignant oral neoplasms.16 The mandible is the most common location for metastases, comprising 80-90% of cases.16 Regardless of the rarity of the metastatic tumors, they should be considered in our differential diagnosis because metastases present with a variable presentation that can mimic inflammatory lesions that are common in the oral cavity and because the involved site in this case is the mandible.16 Most metastatic tumors to the oral cavity are found in patients in their fifth to seventh decade.17 Importantly, metastatic lesions may mimic odontogenic infections and may ultimately be misdiagnosed as pathological entities of dental origin such as pulpal disease.18 Individuals with metastases to the jawbones often have innocuous symptoms that can mimic dental infection.15 The metastatic disease in the jaw may extend into the overlying soft tissue further leading the clinician to suspect an odontogenic infection based on the appearance.15 Radiographically, over 90% of jawbone metastases present as osteolytic lesions.17 These osteolytic metastatic carcinomas in the jaw vary in appearance from well- to poorly circumscribed radiolucencies.15 This fact should remain a consideration here in this case of what was initially thought to be nonhealing root canals. The breast is the most common source of metastatic tumors to the jawbones.18 the identification of a metastatic tumor has a poor overall prognosis for the patient, and death usually occurs in several months.16 The patient in this case had no history of cancer, and the histopathologic examination ruled out metastatic carcinoma. Xanthogranulomas are a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis, which was first described by Adamson in 1905.1 While it is a benign and often self-healing disorder that usually affects infants and children, oral lesions in adults can occur.1 However, these are rare, with only 32 microscopically documented cases in the literature.1,2 Only seven of these 32 cases of oral XG occurred in patients older than 18 years.2 Recently, another case of oral xanthogranuloma in an adult was reported in Taiwan.19 Due to its rarity and clinical and microscopic variability, clinical misdiagnosis can occur. Therefore, clinicians must accurately evaluate and an immunohistochemical finding of the lesion thoroughly if an appropriate and correct diagnosis is to be made.1 histopathologically, xanthogranulomas show a dense infiltrate of histiocytes.3 The lesions also have a variable number of multinucleated giant cells and principally perivascular and perilesional inflammatory cells.3 Eighty-five percent of lesions have Touton giant cells, which are characterized by foamy cytoplasm surrounding a wreath of nuclei and a central area of homogenous eosinophilic cytoplasm.3,4 Immunohistochemical, the lesion is positive for CD68, factor XIIIa, fascin, and alpha-antitrypsin and negative for S-100, CD1a, beta-actin, and desmin.1 Adolescent and adult xanthogranulomas are microscopically the same as the infant lesion, and they also share the same immunohistochemical features.1 Due to its exceedingly rare presentation in the oral cavity, this lesion was included in the differential diagnosis simply because of the histopathologic presentation of Touton giant cells.

The intraoral clinical exam and radiographic findings in this case were not sufficient to definitively rule out any of the entities considered in our differential diagnosis. An oral surgeon performed an excisional biopsy, and tissue from the lesion was submitted for histopathologic examination and immunohistochemical staining. The biopsy specimen consisted of multiple irregular fragments of soft tissue and hard tissue with a yellow purulent internal fluid. Histological examination revealed Touton giant cells-characterized by foamy cytoplasm surrounding a wreath of nuclei and a central area of homogenous eosinophilic cytoplasm-dispersed in an inflammatory infiltrate with mononuclear histiocytes (Figure 2). No epithelium was noted in the biopsy specimen. Immunohistochemical, the lesion was positive for CD68 and factor XIIIa and negative for S-100 (Figure 3). This histopathologic and immunohistochemical presentation led to the diagnosis of xanthogranuloma.

An excisional biopsy was performed and the lesion was removed in its entirety. No additional management was needed beyond periodic recalls to check for recurrence. Excision is the common treatment approach if feasible.2 The size and location of this lesion allowed for appropriate access for excision, so no chemotherapy or radiation therapy were indicated in this case. The patient presented to the oral surgeon three weeks and seven weeks after surgery to assess healing. The site of the lesion showed excellent healing, and the oral surgeon recommended that the patient return in six months to check for healing.

We have reported a case of xanthogranuloma in the mandible found at the apices of two endodontically treated teeth. This case presents a rare lesion of the oral cavity. While the periapical radiolucency surrounding endodontically treated teeth are suggestive of failing endodontic therapy, clinicians must always consider the possibility of something more sinister, necessitating referral to an oral surgeon for biopsy. Xanthogranuloma remains an interesting entity-especially when found intraorally. While the pathogenesis of xanthogranuloma is thought to be reactive rather than neoplastic, it is currently unknown.2 The disease is caused by a proliferation of plasmacytoid monocytes, currently thought to be either a physical or infectious etiology.2 Most xanthogranulomas are characterized by the presence of single or multiple raised cutaneous nodules, yellow-brown to reddish in color.2 The diameter of these nodules ranges from a few millimeters to a few centimeters, and they most commonly involve the head, neck, and upper trunk-an area visible to general dentists.2 After the head, neck, and upper trunk, the most common site is the extremities.2 When an extracutaneous site is involved, the lesion is classified as a systemic xanthogranuloma.20 The most common extracutaneous site is the eye.2 Extracutaneous involvement occurring in bone is classified as Erdheim-Chester Disease.3 Erdheim-Chester disease is a rare histiocytic proliferation that occurs in adults and is characterized by the infiltration of histiocytes into bone and soft tissue.21 Most cases of cutaneous xanthogranuloma do not require treatment and have a favorable prognosis.5 Spontaneous regression has only been reported in the case of one oral lesion.2 If the lesion does not regress, treatment usually consists of surgical excision.2 If surgery is not feasible, radiation therapy or chemotherapy have been used.12‒20 Although rare, systemic xanthogranuloma is associated with significant morbidity and occasional deaths.11 If possible, surgical excision is usually curative for systemic xanthogranuloma as well.20 The Histiocyte Society has established a uniform classification for histiocytic diseases.22 Langerhans cell histiocytosis is categorized as class I, non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses, including xanthogranulomas, are categorized as class II, and the malignant histiocytosis are class III.22 As stated previously, the class II histiocytosis xanthogranuloma is rare in the oral cavity, with only 32 cases documented histologically. Accurate diagnosis requires referral of the lesion for biopsy and microscopic and immunohistochemical examination by an oral and maxillofacial pathologist. In the oral cavity, the extraosseous xanthogranulomas have been found on the gingiva, tongue, tongue base, lip, palate, buccal mucosa, vestibule, and cheek 1. Clinically, xanthogranulomas may appear similar to and may be misdiagnosed as a dental abscess, giant cell fibroma, gingival cyst, fibroma, peripheral giant cell granuloma, peripheral odontogenic fibroma, pyogenic granuloma, lipoma, foreign body irritation, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, granular cell tumor, lymphoid aggregate, verruciform xanthoma, and fibro-epithelial polyp.2‒6 One other very rare diagnostic possibility that should be considered is a periapical granuloma with Touton-like giant cells.23 Given the histopathologic overlap between a true xanthogranuloma and a periapical xanthogranulomatous reactive process-which has the features of a typical periapical granuloma but with Touton giant cells-it is impossible to completely exclude this entity, especially given the location.23 However, we favored the diagnosis of xanthogranuloma given the patient’s medical history because an association exists between xanthogranuloma and other diseases, including neurofibromatosis type I (NF1).3‒24 Moreover, it is known that NF1 patients have a higher occurrence of xanthogranuloma than the general population.24 Ultimately, because the patient’s medical history was significant for NF1, this led us to favor the diagnosis of a true xanthogranuloma over the periapical granuloma with Touton-like giant cells.

This case demonstrates that several lesions can appear at the apex of a tooth, and only biopsy can give definitive diagnosis. As seen through our differential, a variety of entities can present with the clinical and radiographic features seen in this case, ranging from a periapical granuloma to a metastatic carcinoma. With a range of entities, management also can range from something simple like endodontic retreatment or extraction to excision to chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Dentists should always be suspicious of lesions present at the apices of nonhealing endodontically treated teeth because of the possibility of it being something malignant. As stated, xanthogranuloma of the oral cavity can look similar to several more common lesions. This case shows that biopsy is always recommended for lesions that fail to respond to conventional endodontic therapy. Only then can an accurate diagnosis be made using the complete clinical, microscopic, and immunohistochemical presentation of the lesion, which will ultimately allow for appropriate management.

None.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2016 Vargo, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.