Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9943

Case Report Volume 6 Issue 2

1Associate Professor of Dermatology at the Department of Dermatology, Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon - Faculty of Medicine, Balamand University, Lebanon

2Department of Dermatology, Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon - Faculty of Medicine, Balamand University, Lebanon

3Assistant Professor at the Department of Dermatology, Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon - Faculty of Medicine, Balamand University, Lebanon

Correspondence: Paula Karam, Associate Professor of Dermatology at the Department of Dermatology, Saint George Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon - Faculty of Medicine, Balamand University, Lebanon, Tel +961 3 605 757

Received: March 28, 2022 | Published: June 20, 2022

Citation: Karam P, Akl J, El- Kehdy J. Herpes zoster in an immunocompetent child post-covid-19 and meningococcal vaccine: a literature review of herpes zoster post-varicella vaccination in children. J Dermat Cosmetol. 2022;6(2):42-44. DOI: 10.15406/jdc.2022.06.00206

Herpes Zoster in childhood is a rare entity, caused either by infection with the varicella virus or post-vaccination with the live-attenuated varicella vaccine. In both cases, the virus remains dormant in dorsal root ganglia and reactivates at a later stage. The clinical presentation in both cases is a vesicular eruption in a dermatomal distribution. The first-line treatment is Acyclovir. We present a case of childhood herpes zoster that occurred one month after infection with the SARS-Cov-2 virus, four months after vaccination with the varicella zoster vaccine and four days after vaccination with the meningococcal vaccine. To our knowledge, this is the first report in Lebanon of herpes zoster occurring in a 14-months-old girl following COVID-19 disease, not due to infection with the varicella zoster virus (VZV), but rather to the VZV vaccine. Whether the eruption is a direct consequence of the COVID-19 disease, to the meningococcal vaccination, to both, or only a coincidence, remains to be elucidated. A literature review of herpes zoster post-vaccination in the pediatric population, as well as herpes zoster post-COVID infection follows.

Keywords: herpes zoster, reactivation, varicella zoster vaccine, child, covid-19, meningococcal vaccine, pediatric herpes zoster, herpes zoster complications

After its introduction in 1995 as a one-time vaccine, the live attenuated varicella vaccine, which is currently administered as a two-shot series as per the CDC recommendations, is given to most children over the world. The first shot is given around the age of one year and the second between the ages of four to six years old.1 In the United States, this has led to nearly eradicate varicella in children. Vaccination was also shown to decrease the severity and frequency of viral reactivation into herpes zoster (HZ) as compared to when the child acquires the wild-type varicella strain.2 The vaccine is available in three forms; two are monovalent, namely Varilrix® and Varivax®, consisting of the Japanese Oka viral strain, and one is dispensed as a tetravalent vaccine, in combination with the MMR (Measles, Mumps and Rubella) vaccine. However, due to post-marketing reports of a higher rate of febrile seizures with the latter, the first two are preferred, being safe and highly immunogenic.3 Since the end of the year 2019, the world has been affected by a pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, leading to COVID-19. Many studies have been conducted on this virus and its manifestations, including those that affect the skin and mucous membranes among many other organs. Vesicular rashes have been described to be associated with this viral infection, in addition to morbilliform, purpuric, chilblain, urticariform, livedoid, and other rashes.4,5 In addition to these skin manifestations, there has been evidence of reactivation of HZ in the acute and subacute phases of COVID-19.5 Since the varicella vaccine is a live attenuated vaccine, it can cause a latent infection. This is achieved through its ability to persist in the dorsal root ganglia and reactivate at a later stage. Reactivation occurs in either childhood or adulthood, leading to a dermatomal eruption known as herpes zoster.2,3 We present the first and youngest case of VZV reactivation in the form of HZ post-vaccination, post-COVID-19 infection, and post-meningococcal vaccine in Lebanon. The case is followed by a review of the literature.

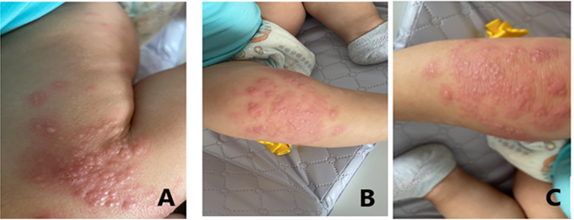

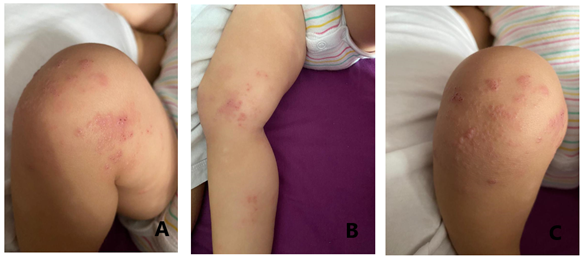

A 14-month-old girl came to our private clinic in Beirut (Lebanon) with a unilateral, painful eruption of the right leg that had started one day earlier. The mother denied any fever or any complaint signaling there might be other systemic symptoms. However, she noted that the child was fussier than usual and cried when someone touched her leg. The patient had a recent history of confirmed COVID-19 infection by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) that occurred one month prior to presentation. The child was otherwise healthy, with a normal growth curve. She had received the varicella vaccine four months prior to presentation as an intramuscular injection in the right thigh, and the meningococcal vaccine four days prior to presentation in the same thigh, and at the site where the lesions erupted. On physical examination, she had a rash consisting of grouped herpetiform vesicles on an erythematous base along the L3, L4 and L5 dermatomes over the right lower extremity, extending from her right thigh to her right foot (Figure 1). It was tender on palpation. The Tzank smear showed multinucleated giant cells, confirming a diagnosis of herpes zoster. She was therefore started on 5.5 ml of Acyclovir Syrup 200mg/5ml four times daily (20-40 mg/kg of body weight, four times daily) for one week. Follow up was done after 36 hours, 3 days, and 6 days. Crusting of the lesions and gradual improvement in the rash was seen (Figure 2), reaching almost complete resolution on day 6 (Figure 3).

Figure 1 A, B, C Patient's lower extremity at presentation, grouped vesicles on an erythematous base can be seen, with a dermatomal distribution along L3/L4/L5 dermatomes .

Figure 2 A,B,C - Patient at day 3 of follow-up, with marked crusting of lesions and notable improvement.

To note that the patient did not have any previous vesicular eruption consistent with varicella infection.

The varicella vaccine has curbed the numbers of varicella cases in children and decreased the severity and incidence of herpes zoster in those who are vaccinated. However, in a few cases, it has been itself the cause of the zoster eruption in immunocompetent children, sometimes even leading to concomitant meningoencephalitis.2 In general, adverse reactions to the varicella vaccine are not numerous, nor life threatening. The most common are reactions at the injection site, fever, diarrhea and to a much lesser extent, a localized or generalized vesicular rash.3,6 These benign adverse reactions have been reported to occur at a rate of 52.7 cases per 100,000 doses. The more severe ones, including zoster, meningitis, septicemia, and even death are reported to occur at a rate of 2.6 per 100,000 doses, affecting mostly immunocompromised patients.6

Herpes zoster (HZ), a dermatomal viral skin eruption, commonly occurs in adulthood, months, but more often years, after varicella. It is the result of reactivation of the Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) that had been dormant in the dorsal root ganglia. It is also seen, albeit rarely, in immunocompetent children who acquired the infection either in utero or very early childhood. It can also occur post-vaccination, as was seen in this case, but less frequently, possibly because the vaccine induces a lower viral load.3,7 The incidence of HZ is 0.74 per 1000 in children younger than 9 years old, while the incidence following vaccination is 14 per 100,000 person per year.2,8 The incidence of HZ increases with increasing age; however, the risk is higher in children who acquired the varicella infection before their first anniversary. This is the most important risk factor for HZ development in children.7-9 Moreover, the interval between varicella infection and HZ is shorter in children who acquired it early on. The latency is estimated at 3.8 years, compared to 6.2 years in those who have had the infection after one year of age.9 On the other hand, the average latency of HZ post-vaccination is around 3.3 years.10

The youngest patient reported to develop HZ post-vaccination is a 15-month-old boy who was previously healthy. He had the varicella vaccine at age of 12 months of age, around 3 months prior to developing HZ in the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve (V1). He was treated with acyclovir. His clinical course was complicated by HZ ophthalmicus, for which the acyclovir course was extended to 10 months.11 Most cases of HZ after vaccination are due to the Oka strain.12 The cause of HZ post-vaccine is yet to be elucidated.10 It has been postulated that childhood HZ is associated with underlying malignancies, although more recent studies have refuted this argument.7 Nevertheless, an association was found between childhood HZ and asthma, the underlying mechanisms of which are still unknown.13

However, on a more important note, an association between the current COVID-19 pandemic and HZ has been noted, where an increase in the cases of HZ has been noted in COVID-19 patients.4 Multiple case reports and case series have described adults in their late 60’s and early 70’s who developed HZ after COVID-19. Some of these cases had severe, necrotic HZ presentation.5,14-16 The latency from COVID-19 infection to HZ development was around 5 weeks, with the shortest being one week and the longest being 10 weeks.5,14,16 Surprisingly, another study presented two cases where COVID-19 infection was diagnosed after HZ, indicating a latent COVID-19 infection.17 It is postulated that the reactivation of VZV in the form of HZ after COVID-19 infection is due to the decrease in the lymphocyte population (T and B lymphocytes) as well as NK cells and monocytes.14,17,18 Another hypothesis is the physiological stress that COVID-19 infection exerts, leading to the reactivation of HZ.19 Notably, no pediatric cases of HZ post-COVID have been reported to date in Lebanon, and our patient is the first.

Herpes zoster post-vaccine, which usually occurs within a few months to a few years in children, can be as severe as the one occurring after regular infection with the wild-type strain of the virus. It can either occur in the same dermatome corresponding to the location of vaccine administration or at a different site.2,8 The most common presentations affect the thoracic nerves, followed by the cranial nerves, particularly the trigeminal nerve. These are followed by the lumbar and sacral nerves.11 In our case, the eruption occurred in the same dermatome in which both the varicella and the meningococcal vaccine were administered. The close proximity between the meningococcal vaccine administration and the eruption raises the question of whether meningococcal vaccine administration was an additional risk factor.

Herpes zoster that follows vaccination presents similarly to zoster following wild-type infection, starting with unilateral pain and a maculopapular rash, followed by the eruption of grouped vesicles overlying an erythematous base. It usually presents in a dermatomal distribution and can also affect adjacent dermatomes. Over the course of the following week, the vesicles usually evolve into pustules, ulcerate, and then become crusted to finally heal within weeks. The mean duration of this evolvement is one to three weeks.7,9 Post herpetic neuralgia is not commonly encountered in children, however, scarring is one of the possible sequelae of this eruption.7,9 Other complications include disseminated zoster, zoster ophthalmicus, Ramsay Hunt syndrome and meningoencephalitis.2,9,11

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) is due to the involvement of the ophthalmic branch of the fifth cranial nerve.11,20 It is a very rare entity in children, with an incidence of 42 per 100,000 person-years.20 HZO presents with the typical skin findings along the trigeminal nerve distribution. If ophthalmic involvement occurs, corneal keratitis and uveitis lead to painful and red eye.20 Ramsay Hunt Syndrome is characterized by tinnitus, loss of hearing and facial nerve paralysis.9 Meningoencephalitis usually occurs within one to two weeks of the onset of HZ.2 The incidence of meningoencephalitis and neurologic sequelae is not defined yet, but they are thought to be rare post-vaccination.21 These patients most commonly present with headache, photophobia, fatigue and vomiting among other symptoms and signs of meningitis. They require prompt diagnosis and treatment to avoid persistence or recurrence of these symptoms, as it has been reported.21,22

The diagnosis is usually based on clinical judgement, but it can be supported with a Tzank smear, or confirmed with a VZV polymerase chain reaction (PCR).7,9 In patients with neurological signs and symptoms, and suspicion of meningoencephalitis, the preferred diagnostic tool is VZV PCR on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). In cases where meningitis is highly suspicious and PCR is negative, testing for VZV-specific IgG immunoglobulins in the CSF can be diagnostic.6

None.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2022 Karam, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.