Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9943

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 2

1Especialista en Medicina familiar y comunitaria. Máster en Medicina estética, CAP La Marina y Hospital Universitario Sagrat Cor, Clínica Tufet, Barcelona

2Doctor en Medicina y Cirugía, Universidad de Barcelona. Coordinador de Proyectos Científicos del Máster en Medicina Estética y del Bienestar, Universidad de Barcelona. Director de IMC-Investiláser, Sabadell, Barcelona

3Coordinador Científico de Medicina Estética (SEME). Codirector del Máster en Medicina Estética y del Bienestar (Universidad de Barcelona). Clínica Alcolea, Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona

Correspondence: Iris Flores Jiménez, Especialista en medicina familiar y comunitaria. Máster de medicina estética, Hospital Universitario Sagrat Cor, Clínica Tufet, Barcelona

Received: April 07, 2022 | Published: May 27, 2022

Citation: Flores -Jiménez I, Martínez-Carpio P, Alcolea JM. Efficacy and safety of facial treatments with polylactic acid. Systematic review. J Dermat Cosmetol. 2022;6(2):32-37. DOI: 10.15406/jdc.2022.06.00204

Introduction: Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) is a synthetic polymer from the family of poly alpha-hydroxy acids widely used in aesthetic medicine. It induces a controlled inflammatory reaction to a foreign body, with formation of new collagen; therefore, it is considered not only a facial filler but also a bioimplant.

The aim of this work is to study the efficacy and safety of PLLA as a facial filler based on the current literature.

Material and methods: After a systematic review of the Medline database (PubMed), 43 valid articles were obtained. Studies were included: interventional, randomized and non-randomized clinical trials. In addition to observational, prospective and retrospective studies, whenever PLLA was injected in the facial area.

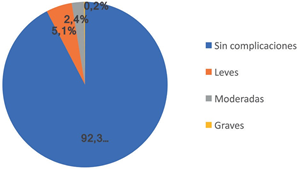

Results: The overall efficacy (OE) of PLLA in skin rejuvenation was 93%, in lipodystrophy 74% and in acne scars 68%. The total OE was 78%. Of the patients injected with PLLA, 92.3% had no complications, 5.1% mild complications, 2.4% moderate complications and only 0.2% severe complications.

Conclusion: PLLA requires a refined technique to perform the treatment, although it presents varied indications and multiple advantages: prolonged permanence of its results, high efficacy and adequate safety profile.

Keywords: Poly-L-lactic acid, PLLA, Sculptra, New-Fill, facial filler, skin rejuvenation, lipodystrophy, acne, nodule, granuloma

APLL is a polymer of the poly alpha-hydroxy acid family, originally synthesized by French chemists in 1954 and used safely as a suture material, in resorbable plates and screws in orthopedic, neurological and craniofacial surgery. In Europe it was approved in 1999, under the name of New-Fill® and for aesthetic purposes, to restore the volume of depressed areas such as folds, wrinkles or skin scars.1 In 2004 it was approved by the FDA for soft tissue restoration in lipoatrophy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Later, in 2009, under the name of Sculptra® (Dermik Laboratories, Berwyn, PA, USA), its use was extended to aesthetic medicine, expanding its facial indications to body ones, such as hands, neck, breasts or atrophic scars.2

The product is presented as a lyophilized powder containing APLL microparticles of 40 to 63 µm in diameter, in a base of carboxymethylcellulose and non-pyrogenic mannitol.3 APLL microspheres elicit a subclinical foreign body inflammatory response, leading to their encapsulation, approximately one month after injection.4 At 6 months, coinciding with the disappearance of the inflammatory response, there is evidence of an increase in type I collagen fibers in the extracellular matrix that is maintained for 8 to 24 months.5 Recent studies have also shown the presence of collagen type III.

Due to the neocollagenesis that it produces, the APLL is considered not only a facial filler but also a bioimplant. Over the course of 9 months, APLL microparticles hydrolyze into monomers which, through lactic acid degradation, are excreted by respiration in the form of CO2 and wáter.4

The most common adverse effects of APLL injection include pain, erythema, ecchymosis, edema, pruritus, allergic reactions, minor bleeding, and minor bruising, although the most prominent complication is nodule formation. These nodules can be granulomatous or fibrous;6 the latter are believed to be caused by an inadequate application technique.7 In contrast, granulomas are usually due to an allergic or inflammatory reaction of the host that can last up to 18 months.8 Histopathologically, granulomas present as fragments of APLL particles that are oval, fusiform, or pointed, birefringent on examination with polarized light, and surrounded by giant multinucleated cells that are arranged in a palisade in order to isolate it from the surrounding tissue.8,9

More serious, although less frequent, complications secondary to inadvertent vascular occlusion have been described. High-risk anatomical areas are the glabellar region, the temples, the central area of the forehead, the nasal pyramid and alar groove, the nasolabial folds and lips. The arteries most exposed to occlusion are: supratrochlear, supraorbital, angular, dorsal nasal, lateral nasal, superficial temporal, and superior and inferior labials.10

Bacterial, viral (Herpes simplex) or fungal (Candida Spp.) infections can also occur, although they are rare. In the case of bacterial infections, if they occur early they are usually due to Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes;11 on the contrary, if they do so more than 2 weeks after treatment, they are usually due to atypical microorganisms such as mycobacteria and Escherichia coli. On rare occasions they can form biofilms.

Proper reconstitution, hydration, handling and placement of the product are essential to avoid adverse effects; In addition, correct asepsis and antisepsis measures must be followed. The incidence of fibrous nodules decreases markedly when higher volumes (between 8 and 9 ml) are used for the reconstitution of the lyophilisate, longer hydration times (up to 48 hours), the injection of the product is carried out at the supraperiosteal level (in amounts per point not higher than 0.3 to 0.5 ml/cm²) or in the upper portion of the subcutaneous fat (advisable not to exceed 0.1 to 0.3 ml/cm²) instead of in the lower dermis.7 Post-treatment massage is essential to disperse APLL particles and prevent nodule formation.2 Another detail to be taken into account is not to make the injections in, or through, active muscles; particularly in the m. orbicularis oculi or lips, where the nodules would be produced by entrapment of the product in the muscle fibers due to its special movement.

Palpable fibrous nodules can be removed by injection of corticosteroids or hyaluronic acid intralesionally and into the surrounding area. Recently, injection of an antimitotic, 5-fluorouracil, has been shown to offer less risk of skin atrophy compared to corticosteroids. Likewise, in granulomas, injection of corticosteroids or 5-fluorouracil is also indicated, and oral hydroxychloroquine or allopurinol can be used.12 The use of surgical excision is controversial; some authors warn about the risk of fistula or abscess formation, while others defend ultrasound-guided curettage.13

The risk of APLL presenting late immune reactions is minimal, it could be said that it is biocompatible and absorbable and, due to the increase in collagen that it induces (neocollagenesis), it can be considered a long-lasting filler.2,9

Search strategy

A systematic review of the existing literature was carried out without a time limit, with the aim of obtaining scientific articles related to the efficacy and safety of polylactic acid. These articles were obtained using the polylactic fillers descriptors in the search strategy, in the Medline (PubMed) database until March 2021. 420 articles were obtained from this initial search. Of these, 270 articles were eliminated in which the APLL was not used for aesthetic purposes but for other medical or non-medical uses. In addition, another 9 articles that did not refer to the APLL or that were no longer available were eliminated. After this first filter, 141 articles related to aesthetic medicine remained.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All randomized and non-randomized clinical trials, prospective single-based and retrospective observational studies, and case series in which APLL was injected into patients in the facial area and published in English, French, or Spanish were included. Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and studies of any body area other than the face, or carried out on animal models, were excluded. In the end, 43 articles that met the established selection criteria were selected. For the review, the full text of all the selected articles was read (Figure 1).

Of the 43 articles selected, no studies prior to 2004 were found; 8 of them (18%) date from 2009. It should be noted that 18 articles (42%) only studied cases or case series of 5 or fewer patients.

The safety of the APLL was evaluated in 42 of the 43 articles, 98% of those studied. However, efficacy was only taken into account in 24 of them (56%). In both cases, the number of patients (n) treated in each study and the time (t) in months of maximum follow-up after the application of the filler were considered. For the statistical analysis, the arithmetic mean (m = average) as a measure of central tendency and the range (r = range) as the degree of dispersion have been used as descriptive indicators.

Safety results

To study clinical safety, the number of patients who presented complications (nC) was quantified, assigning a numerical value according to their severity:

The total population of the studies was 1,801 patients, of whom 1,663 (92%) did not present complications or had expected mild adverse effects, such as erythema, pain, ecchymosis, edema, pruritus, mild and local allergic reactions, punctual or small bleeding. hematomas, whose resolution took a few days (Table 1).

Bibliography |

nC |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

t |

Olivier Masveyraud9 |

298 |

284 |

11 |

3 |

0 |

84 |

Monheit et al.11 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

18 |

Daines et al.12 |

811 |

805 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

60 |

Wolfram et al.13 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

24 |

Zhang et al.19 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

Lafaurie et al.39 |

64 |

36 |

28 |

0 |

0 |

21 |

Ragam et al.15 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.25 |

Bohnert et al.18 |

33 |

33 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

Lin et al.26 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

12 |

Bachmann et al.27 |

22 |

17 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

61 |

Rossner et al.36 |

22 |

0 |

9 |

13 |

0 |

96 |

An et al (2019) |

36 |

36 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

18 |

Shahrabi-Farahani (2014) |

12 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

0 |

29 |

Fiore et al.14 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

Eastham et al (2013) |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

Bachmann et al.27 |

5 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

59 |

Tangle et al (2010) |

30 |

30 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

24 |

Poveda et al (2004) |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

Cox22 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

18 |

Byun et al.10 |

20 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

Yuan et al.17 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.5 |

Kates et al.20 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

O´Daniel33 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

29 |

Chen et al.43 |

14 |

13 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

16.5 |

Not et al (2015) |

58 |

56 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

24 |

Nelson et al.21 |

10 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

36 |

Sapra et al.23 |

22 |

21 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

Hyun et al.28 |

30 |

29 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

Van Rozelaar et al.31 |

26 |

22 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

13.5 |

Stewart et al.34 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

8.5 |

Schierle et al.30 |

106 |

101 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

24 |

Averey et al (2010) |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

12 |

Roberts et al.16 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

Salles et al.32 |

10 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

36 |

Alijotas-Reig et al.8 |

10 |

0 |

5 |

5 |

0 |

53.2 |

Narcissus et al (2009) |

33 |

32 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

6.5 |

Borelli et al.37 |

12 |

12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

Guaraldi et al.38 |

35 |

27 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

24 |

Burgess et al.41 |

61 |

59 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

24 |

Sadick et al.24 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

25 |

Sadov et al.25 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

54 |

Woerle et al.4 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

n = 1,801; ∑n = 42.88; nC=138; ∑nC = 2.5; 0 = 1,663, 1 = 92.2 = 43.3 = 3; ∑t = 23.9 (r = 0.25 - 96) |

||||||

Table 1 Table 1 This table shows the rresults of the security analysis in the use of the APLL

Complications occurred in 138 patients, which represents 7.7% of the total number of cases studied; in 92 patients (5.1%) they were mild, in 43 (2.4%) moderate and in 3 of them severe (0.2%) (Figure 2). In turn, among the mild complications, there was only one case of allergic reaction.

Figure 2 Percentage of patients with complications: 92.3% of the patients did not present complications, in 5.1% they were mild, 2.4% moderate and 0.2% severe.

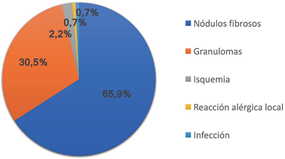

gic; the rest, 91 patients, presented fibrous nodules. Of the 43 patients with moderate complications, one case was attributed to local infection by Mycobacterium mucogenicum; while the other 42 patients had granulomas.14 Of the 3 serious complications, 2 were cases of blindness; one due to acute ischemia of the optic nerve, due to occlusion of the central retinal artery, with extension to the frontal lobe, and another case due to orbital ischemia.15,16 The third case was due to occlusion of the mental artery.17 The patients studied had a follow-up period of around 24 months.

Considering only the complications that the 138 patients had, it should be specified that they were mild in 66.7% of the cases, 65.9% corresponding to fibrous nodules; in 31.1% they were considered moderate, the majority being granulomas (30.5%); Of the serious cases, 2.2% corresponded to ischemia, while the cases of allergic reaction and infection represented 0.7% each (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Type of complications: The graph shows the distribution of the type of complications: 65.9% were fibrous nodules; 30.5% corresponded to granulomas; 2.2% were ischemic alterations; 0.7% local allergic reactions and 0.7% local infections.

Efficacy results

Efficacy was analyzed in 24 articles as follows:

Given that the articles grouped together different applications in their study, the efficacy of each one was evaluated separately. The evaluation of the clinical efficacy (CE) of the treatments was carried out using a semi-quantitative scale to which the values were assigned as follows: –1, worsening; 0, no or little efficacy; 1, moderate; 2, good; 3, very good. To score each work, the results of the diagnostic tests were taken into account.

Weighted clinical efficacy (WCE) is defined as the product of multiplying the CE by the number of cases (n), with the global or group efficacy (GE) being the ratio between the ECP and the maximum clinical efficacy (MCE). The average value of each case in the articles that studied case series was also considered. In relation to the above, the efficacy results of APLL treatments have been obtained in 3 clinical situations:

Skin rejuvenation.The GA in skin rejuvenation calculated on the treatments in 512 patients was 93%, with a mean follow-up of 26 months (Table 2).

Bibliography |

n |

EC |

ECP |

ECM |

t |

Masveiraud (2009) |

298 |

3 |

894 |

894 |

84 |

Bohnert et al.18 |

33 |

2 |

66 |

99 |

12 |

Byun et al.10 |

20 |

2 |

40 |

60 |

12 |

Chen et al.43 |

14 |

2 |

28 |

42 |

16.5 |

Hyun et al.28 |

30 |

2 |

60 |

90 |

6 |

Schierle et al.30 |

106 |

3 |

318 |

318 |

24 |

Salles et al.32 |

10 |

2 |

20 |

30 |

36 |

Woerle et al.4 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

16 |

n = 375; ∑n = 31.25; ∑EC = 2.25(r = 2-3); ∑ECP = 69.5; ∑ECM = 3n = 93.75; EG = ∑ECP/∑ECM = 0.74 = 74%; ∑t = 16.58 (r = 2-36) |

|||||

Table 2 Results of the efficacy of APLL treatment in skin rejuvenation

The GA in lipodystrophy on the results in 375 patients accounted for 74%, with an average follow-up of 17 months (Table 3).

Bibliography |

n |

EC |

ECP |

ECM |

t |

Lafaurie et al.39 |

64 |

2 |

128 |

192 |

21 |

Zhang et al.19 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

6 |

Tangle et al (2010) |

30 |

3 |

90 |

90 |

24 |

Kates et al.20 |

2 |

3 |

6 |

6 |

12 |

Nelson et al.21 |

10 |

1 |

10 |

30 |

36 |

Van Rozelaar et al.31 |

26 |

2 |

52 |

78 |

13.5 |

Narcissus et al (2009) |

33 |

2 |

66 |

99 |

6.5 |

Borelli et al.37 |

12 |

2 |

24 |

36 |

6 |

Guaraldi et al.38 |

35 |

2 |

70 |

105 |

24 |

Burgess et al.41 |

61 |

3 |

183 |

183 |

24 |

Woerle et al.4 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

Ong et al (2007) |

100 |

2 |

200 |

300 |

24 |

n = 375; ∑n = 31.25; ∑EC = 2.25 (r = 2-3); ∑ECP = 69.5; ∑ECM = 3n = 93.75; EG = ∑ECP/∑ECM = 0.74 = 74%; ∑t = 16.58 (r = 2-36) |

|||||

Table 3 Results of the efficacy of APLL treatment inlipodystrophy

Acne scars.The GA in the treatment of secondary acne scars, calculated on 61 patients, was 68%, reaching an average follow-up of 27 months (Table 4).

Bibliography |

n |

EC |

ECP |

ECM |

t |

An et al (2019) |

36 |

2 |

72 |

108 |

18 |

Sapra et al.23 |

22 |

2 |

44 |

66 |

12 |

Sadick et al.24 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

25 |

Sadov et al.25 |

2 |

3 |

6 |

6 |

54 |

n = 61; ∑n = 15.25; ∑EC = 2.5 (r = 2-3); ∑ECP = 31.25; ∑ECM = 3n |

|||||

= 45.75; EG = ∑ECP/∑ECM = 0.68 = 68%; ∑t = 27.25 (r= 12-54) |

|||||

Table 4 Results of the efficacy of APLL treatment in acne scars

The above results result from studying the GA of each subgroup separately. Collectively, the arithmetic mean of the GAs of the APLL treatments is 78%; calculated on 948 patients with an average follow-up of 23 months (Figure 4).

The efficacy review shows that one of the main indications for treatment with APLL, in which the best results are achieved, is skin rejuvenation; since it offers an objective improvement in the quality of the skin. This high efficacy indicates that APLL injections achieve an effect of increasing the volume and thickness of the skin as they are capable of generating new collagen.1,2,4,5 In addition, APLL has a rejuvenating effect on the skin quality, increasing hydration and, therefore, its elasticity, while reducing pore dilation, providing softness and reducing hyperpigmentation.9 On the other hand, it has been hypothesized that APLL injections directed at the deep dermis stimulate adipose stem cells in the upper hypodermis, which would induce them to secrete growth factors, contributing to the regeneration of adipose cells. tissues through the biostimulation of fibroblasts with the consequent rejuvenation of the filling area.10

The use of APLL and the efficacy of treatment in lipodystrophy have been extensively studied, mainly in patients receiving antiretroviral treatment for HIV infection.18-20 In these cases, the good result achieved by the volume effect and the improvement in skin texture are combined with the psychological benefits of the APLL injection by eliminating the social stigma of HIV-positive patients.21 However, although the use of APLL entails a high degree of efficacy in the treatment of lipodystrophy, some authors defend that other techniques such as lipotransfer could be more effective; although this technique is not exempt from adverse effects and patients must have an adequate donor area, considering that lipoatrophy is not exclusive to the face.22

Another pathology in which the use of APLL injections has been shown to be effective is in the treatment of scars secondary to forms of severe acne. Although the degree of efficacy achieved is not as high as in the other conditions analysed, rejuvenation and lipodystrophy, it should be remembered that the number of patients taking part in the clinical studies analyzed is considerably lower.23-25 In addition, scars caused by acne, especially those called "ice pick" require combined treatments for their attenuation, such as those offered by fractional Er:YAG and/or CO2 lasers.

Treatments with APLL are not without risk, as can be deduced from the analysis carried out.26–28 In general, any practice with injectable filler materials may present local adverse effects, inherent to the technique itself, such as pain, erythema, ecchymosis, edema, pruritus, or bruising.29 These undesirable effects are to be expected, and their complete resolution in a short period of time means that they are not taken into account in safety studies.30–33

If the inflammatory reaction is persistent, it is called a complication. Although it is true that major complications occur in a very small percentage of patients, the doctor must be aware of them in order to treat them immediately. It has been proven that the most frequent complication after the application of APLL is the formation of fibrous nodules.34,35 A refined practice, together with a good injection technique and exhaustive knowledge of the anatomical planes, together with the correct reconstitution and hydration of the PLLA, will reduce the incidence of the appearance of these nodules.36,37

Another important aspect is the obligatory application of the pertinent rules of asepsis and antisepsis before, during and after any treatment with injectables. In this sense, it is noteworthy that, of the articles analyzed, only one describes a complication due to bacterial superinfection.14 However, the formation of granulomas is a noteworthy complication, representing the most important fraction of them.38–40 Allergic reactions, on the other hand, occur in a very small number of patients, estimated at 0.7% of cases.11,12

Serious complications are, fortunately, very rare (0.7%); highlighting the fact that 2 of the 3 patients in whom they occurred were HIV positive.8,12 This could be due to the fact that more studies have been carried out in HIV-positive patients as there is a clear indication for the treatment of lipodystrophy with APLL. However, it could be considered that it is a virus that has been described as potentially prothrombotic, a fact that would favor the appearance of ischemic events.15-17

The results obtained from the use of the APLL in this analysis show highly favorable results for its use.41,42 Although the limitations of the present study should not be forgotten; The first is subjectivity, mainly in the evaluation of GA, since the assignment of numerical values followed a semi-quantitative scale adapted for this purpose, as a way of standardizing the values based on the results of the complementary tests and scales. of satisfaction granted by the respective authors. The second to consider is the lack of articles with sufficiently precise CE assessments, especially those referring to acne, which could constitute a bias for the results.

Finally, it should be mentioned that there is a lack of clinical efficacy studies that are not only based on complementary examinations, but should also be based on quality photographic records evaluated by independent observers.43

The indications for treatment with APLL have not stopped growing. Its application provides numerous advantages, highlighting the prolonged duration of its effects due to the induced stimulus on neocollagenesis. It is necessary to highlight the high efficacy of APLL treatments and the high safety profile it presents. APLL is a product that should be used by expert doctors, as it requires a more refined application technique than other filler products.

None.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2022 Flores, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.