Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9943

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 4

1Facial Plastic Surgery, Ultimate Medica, México City, México

10Contour Clinics, Sydney, NSW, Australia

11Galderma Australia Pty Ltd, North Sydney, NSW, Australia

12Cosima Medispa, Edgecliff, NSW, Australia

2Maxillofacial Surgeon, Perth, WA, Australia

3Cosmetic Physician, Ellumina Cosmetic Clinic, Sydney, NSW, Australia

4EverKeen Medical Centre, Tin Hau, Hong Kong

5Director of Plastic Surgery Department, Shanghai Tongji Hospital of TongJi University, Shanghai, China

6Private Practice, Aesthetic General Practitioner, Seoul, Korea

7Cosmetic Physician, AIC Clinic, Bangkok, Thailand

8Privee Clinic, Jakarta, Indonesia

9Mount Elizabeth Hospital, Singapore

Correspondence: Frank Rosengaus, MD, Facial Plastic Surgery, Ultimate Medica, Anatole France 145, Colonia Polanco, México City, CDMX, 11550, México, Tel +52 55 5281 3133

Received: October 25, 2023 | Published: November 8, 2023

Citation: Rosengaus F, Morlet-Brown K, Woo M, et al. Balancing Act: Considerations for profiloplasty assessment in patients presenting for treatment with dermal fillers. J Dermat Cosmetol. 2023;7(4):136-142. DOI: 10.15406/jdc.2023.07.00250

Background: Dermal fillers are increasingly being used in profile aesthetic correction, but what happens if treatment is commenced without considering the impact on the inter-relationship between the nose, chin and lips in the lateral view?

Objectives: Explore the relationship between these three profile features and provide a framework to help standardise the order in which they are assessed when preparing dermal filler treatment plans for profile correction.

Methods: Literature review informed the development survey on profile aesthetics and assessment. Survey results were analysed descriptively and presented to a focus group comprising cosmetic physicians and plastic surgeons. This group reviewed validated assessment scales and incorporated these into a 3-step assessment framework, which was pilot-tested on a convenience sample of patients presenting prospectively for minimally invasive aesthetic treatment.

Results: There was a 95% survey response rate (38/40 surveys completed). Facial feature proportion was rated the most important factor when determining profile attractiveness (average score 9.11) and the nose was ranked the primary feature contributing to the determination of profile attractiveness. The assessment framework begins with the nose, followed by the chin and then the lips and includes validated assessment scales and standard angles and lines. Results from pilot testing showed that by first balancing the nose, other key profile features could then be harmonised.

Conclusions: In patients presenting for cosmetic injections to correct profile aesthetics the assessment framework provides a simple solution to enhance clinician-patient discussion and inform holistic treatment planning. Wider testing and validation are warranted.

Keywords: assessment, hyaluronic acid, profile, nose, chin, lip, real world experience, consensus, aesthetics

GCRS; Galderma Chin Retrusion Scale

The concept of having a specific balance between the nose, the lips and the chin in the profile view was formally introduced by Ricketts in the 1950s1 and continues to be advocated in contemporary surgical texts addressing profile anatomy.2 In accordance with this, studies of facial profile aesthetic preferences note that the harmony between the nose and the chin overrides the importance of their individual dimensions,3,4 and that compensatory lip protrusion can be used as a strategy to improve perceptions of profile attractiveness in cases of chin or nose protrusion.5

The evolution of dermal filler products enables a non-surgical option for patients who want to improve facial aesthetics without the downtime, risks and costs of surgery.6,7 When considering the use of dermal fillers for profile aesthetic correction, validated metrics and standard lines for assessment are established.1,8-12 Extensive guidance on anatomy, underlying vasculature and optimal treatment (technique, product choice, safety considerations) is also available.7, 13-22 However, patients seeking treatment with cosmetic injectables tend to identify a single feature that needs correcting. This can cause “perception drift”23 resulting in implementation of hyper-focused treatment plans that may inadvertently lead to unnatural results.24

What happens to profile harmony if we assess and treat only the feature that patient is most concerned about, without considering the impact on the inter-relationship between the other features? We hypothesized that the order in which key facial profile features are assessed could help to address this question by highlighting the logic behind a more holistic treatment plan. The aim of this work was therefore to develop a step-by-step facial profile assessment framework for use in patients presenting for dermal filler treatment.

As part of a wider research project investigating different facets of aesthetic medicine,25 a Scientific Exchange Working Group, comprising two of the authors (FR and KMB), three Dermatologists, two Cosmetic Physicians and a Specialist Plastic Surgeon, convened to discuss their current clinical practices. A literature review then informed the development of a survey, which 40 aesthetics practitioners from the Asia-Pacific region were invited to complete. The survey tool comprised 37 custom-written questions designed to capture demographics and respondents’ perceptions of different factors relating to assessment of skin quality, lip, eyelid and profile aesthetics. With specific relevance to this paper, there was one question regarding features contributing to general overall aesthetic first impression and five questions specifically pertaining to profile assessment. Survey data were summarised descriptively using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software LLC, Boston, MA, Version 9.3.1).

Two of the authors (FR and KMB) chaired a hybrid (in-person, on-line) focus group meeting during which the profile assessment survey results were discussed. The group reviewed validated assessment scales and discussed how to incorporate them into a step-by-step profile assessment framework. Agreement on the proposed framework was achieved via consensus without formal voting. Members of the focus group were then invited to trial the proposed framework in a prospectively selected patient presenting for minimally invasive aesthetic treatment. After obtaining written patient consent, practitioners completed an observation record at baseline and after each assessment and treatment step. To ensure diversity of case studies, subjects were selected based on convenience with no predefined eligibility criteria. The case studies are presented as a demonstration of how the assessment framework can be applied in the non-surgical setting.

Practitioner survey: A total of 39 practitioners returned the survey (response rate: 98%); demographics are summarized in Table 1. Preferences for ideal profile aesthetics and gonial angles demonstrated some sexual dimorphism, with the majority of respondents selecting a convex profile (68%) and a gonial angle of 120-140° for females and a straight profile (89%) with a more acute gonial angle for males.

|

N (39) |

Proportion |

|

|

Medical Specialty |

||

|

Cosmetic physician |

21 |

55% |

|

Dermatologist |

8 |

21% |

|

Surgeon (Plastic/Cosmetic) |

6 |

16% |

|

Primary care physician/General Practitioner |

2 |

5% |

|

Oral maxillofacial surgeon |

1 |

3% |

|

Country of residence |

||

|

Mexico |

1 |

2.50% |

|

Brazil |

1 |

2.50% |

|

Portugal |

1 |

2.50% |

|

Indonesia |

1 |

2.50% |

|

Philippines |

1 |

2.50% |

|

New Zealand |

2 |

5.00% |

|

Hong Kong |

2 |

5.00% |

|

Korea |

2 |

5.00% |

|

China |

2 |

5.00% |

|

Singapore |

3 |

7.70% |

|

Thailand |

3 |

7.70% |

|

Taiwan |

3 |

7.70% |

|

Australia |

18 |

46.00% |

|

Number of years practicing aesthetic medicine |

||

|

5-10 years |

3 |

8% |

|

> 10 years |

36 |

92% |

Table 1 Survey participant demographics

When considering the first impression of overall aesthetics, facial proportion was ranked the most important factor (average ranking score 3.34), but was not significantly more important than facial profile (average ranking score 5.45, p=0.225). Facial feature proportion was rated the most important factor in the determination of profile attractiveness (average score 9.11). This factor was rated more highly than facial landmarks/geometric features (average score 7.95, p=0.0364), but not profile contour (average score 8.63, p>0.999). The nose was ranked the most important facial feature contributing to profile aesthetics, followed by cheek prominence, the chin and the lips. The forehead and submentum each ranked significantly lower than did the nose, cheek prominence and chin (Figure 1).

When asked to select facial features of most importance to the attractiveness of the feminine facial structure, the nose (p=0.012), cheek (p<0.0001) and jawline (p=0.0007) were each ranked significantly higher than the brow ridge. Results for the masculine facial structure significantly favoured a square, chiselled lower facial contour (average ranking score 1.61) over a prominent brow ridge (average ranking score 3.61, p<0.0001).

Tailoring assessment approaches to the features that need to be brought into balance

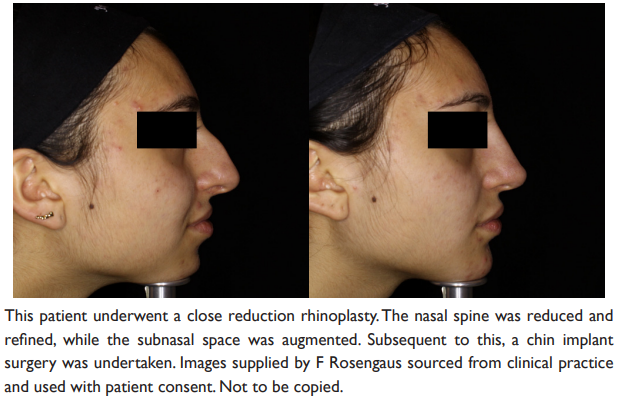

The focus group agreed that (1) comprehensive profile assessment should ideally use a range of existing tools and metrics and (2) there is a need to distinguish and refer patients more suited to surgical intervention before proceeding with assessment for dermal filler treatment. There was a high level of agreement within the focus group that the nose, being central to the midface, was a key element of the facial profile. However, the focus group determined that only cosmetic injectors of the appropriate skill level should perform non-surgical rhinoplasty. Injectors should be cognizant of the limitations of this procedure, referring patients with significant nasal deformities (as in the example in Figure 2) and setting reasonable expectations with the patient.

Figure 2 Example of patient in whom surgical rhinoplasty would be of more benefit than dermal filler rhinoplasty

In the context of a patient presenting for treatment with dermal fillers, they determined that use of current assessment tools did not provide clear guidance as to which feature to treat first to ensure that an imbalance in the patient’s profile was not created. They noted that the established Rickett’s line1 supported the concept of a specific aesthetic relationship between the nose, lips and chin, and that the survey results had suggested these facial features to be of most importance when considering the profile. They concurred that evaluating the relationship between the nose, chin, and lips could offer a feasible means to determine which feature is contributing most to imbalance of the profile. In the context of applying dermal filler treatment, the focus group agreed that the preferred order of treatment should be based on their ideal relative projection – first the nose, then the chin, and lastly the lips (Figure 3). The group then discussed standardized lines and validated assessment scales to determine which would be practical to apply in the non-surgical setting (See: Figure 4: Nose, Figure 5: Chin and Figure 6: Lips).

Figure 6 Lip assessment: Applying modern metrics to the Rickett’s Line.1

Step 1: Nose assessment

Formal assessment of the nose requires an understanding of proportions, ratios and angles. On the profile view, the nasofrontal angle (Figure 4A), is formed at the transition point between the nose and the forehead, where the glabella and the nasal dorsum merge. The Goode method26 (depicted in Figure 4B) is proposed for measuring nasal tip projection, a vertical line is drawn from the nasion to the alar groove (nasal length) and a perpendicular line is drawn from the alar grove to the tip (pronasion).

Step 2: Chin assessment (Figure 5)

The Galderma Chin Retrusion Scale (GCRS) uses a vertical line drawn from the vermillion border of the lower lip to determine the extent of chin retrusion based on a scale of 0 (none) to 3 (severe).27 Chin retrusion is present if the most anterior portion of the chin is recessed from this vertical line. The scale then uses two additional vertical lines, the oral commissure and the midway line, as consistent landmarks to further determine the extent of the retrusion. Where there is difficulty visualizing the most anterior portion of the chin, the extent of retrusion should be evaluated using the chin midpoint (the midpoint between the labiomental sulcus and the inferior point of the chin). The assessment framework (Figure 3) divides patients with retrusion into two groups; those with mild/moderate retrusion are candidates for corrective treatment with dermal fillers while those with severe retrusion are candidates for surgery.

Step 3: Lip assessment (Figure 6)

There was a strong consensus within the focus group that in modern esthetics there is a bias towards bigger lips (the Kardashian effect). The focus group therefore agreed that the original Rickett’s Line1 had moved forward by 2 mm, such that the currently upheld ideal aesthetic line is that the lower lip should reach the line with the upper lip 2 mm behind it (Figure 6). While there are ethnic differences in the measurements, and changes in what are considered the most esthetics metrics, common observations can be applied such that the nose and chin will dominate when the lips are further behind the line and the lips will dominate the closer, they are to the Rickett’s Line.

Real world application of the assessment framework

Case 1 (Figure 7): Initial assessment of this 39-year-old Asian male determined that his nose was under projected and 0.3ml of Restylane Lyft was injected into the columella to increase protrusion. Use of the GCRS revealed the patient to have moderate chin retrusion and 2ml of Restylane Lyft was added to increase chin protrusion and widen the sides of his chin. Application of the Rickett’s line to the patient’s newly enhanced nose and chin showed mild recession of the upper lip and 0.2ml of Restylane was used to increase protrusion. This practitioner rated the ease of use of the scale and their satisfaction with the overall results as both being 10/10, highlighted the value of systematically examining and treating areas of concern.

Case 2: A 46- year-old Caucasian female presented for aesthetic improvement (Figure 8). Using the assessment framework the nose was assessed first and it was determined that tip projection was needed. The dorsum was regularized while camouflaging the mixed bone/cartilage hump and, at the same time, conserving the correct nasofrontal angle. Tip projection and rotation was attained with the application of 0.5ml of Restylane Lyft at the base of the nose and in the columella. The chin was then assessed; it was noted that the patient had minimal retrusion and it was determined that she did not need further treatment in this area. In the final assessment step, application of the Rickett’s line to the lips, hyper-projection was observed. The patient had reported this to be the result of previous application of fillers. In this case, hyaluronidase was used to bring the upper lip into balance with the rest of the profile. This practitioner noted that following a stepped approach enabled appropriate consideration of the each of the elements of the profile both individually and as a whole and highlighted that in doing so it became easier to see what needed to be corrected to achieve overall balance.

Case 3: This 45-year-old Middle Eastern female’s nose was adequately projected, but her chin showed moderate to severe retrusion on the GCRS (Figure 9). The practitioner explained the assessment scale to the patient who found it informative and easy to understand. During the discussion, the patient conveyed their desire for conservative treatment, and it was decided that use of filler to project her chin would be an appropriate first step. A total of 1ml Restylane Lyft and 1ml Restylane was used, with 1ml for central protrusion and 0.5ml on either side of the chin to blend. Application of the Rickett’s Line showed much improved proportion of the upper and lower lips, despite the patient’s new chin still showing mild retrusion. The practitioner noted that improving the chin further would then require lip projection. It was decided that further improvements could be made in the future depending on the patient’s comfort level and situation. This practitioner commented that the stepped assessment approach was simple to use and easy to incorporate into practitioner-patient treatment planning discussions.

Case 4: This 31-year-old Latino female presented initially seeking lip enhancement (Figure 10). The assessment framework was applied, starting with the nose it was determined that rotation and tip projection were required. Using the standard angles as a guide, dorsum regularization and nasofrontal angle correction were achieved and then nasal rotation was achieved by rectifying the nasolabial angle. Then the tip was projected in accordance with the new dorsum height. A total of 0.5ml Restylane Lyft was used for the nose. On applying the GCRS, the chin was found to have mild retrusion. To address this two paramedian boluses of 0.3ml Restylane Lyft were applied supraposterially. This resulted in anterior projection and extending the width of the chin. In the third step, the lips were treated with 0.5ml Restylane Kysse to achieve projection close to the Rickett’s line. This practitioner was very happy with the overall stepped assessment approach, commenting that it had made it easier to communicate each treatment step to the patient and that the patient had a better understanding of why each of the products were being used.

The relationship between the nose, chin and lips needs to be preserved to retain balance in the profile view.2,3,5,28,29 The current work explored this relationship to develop a facial profile assessment framework designed specifically for use when preparing dermal filler treatment plans for profile correction. The intent of this proposed framework was to provide a structured system to help enhance communication between cosmetic injectors and their patients and overcome the potential pitfalls of hyper-focused treatment plans. Survey results demonstrated that experienced clinicians place high value on facial feature proportions as a key component of an attractive profile and ranked the nose as the feature contributing most to their determination of profile attractiveness. These findings, when discussed in a peer group setting, led to the development of a proposed framework, wherein the nose is assessed first followed by the chin and then the lips, with each subsequent assessment considering the impact of the prior one on the overall profile. Application of this step-wise approach in a limited number of patient cases highlighted the ease with which it could be used and the added clarity it brought to patient communication and overall treatment planning.

There are established, extensive clinical assessment protocols for patients undergoing orthognathic surgery for facial profile improvement30,31 and for those undergoing rhinoplasty.2,28,29,32–38 The proposed framework incorporates the use of a validated chin retrusion assessment scale27 and standard angles and lines for nose tip26 and lip1 projection. While these metrics are fewer than are suggested in the surgical setting, they include simplified assessments to determine the nasofrontal angle, tip projection and discrepancies in the lip-chin relationship which are appropriate for correction in patients presenting with mild cosmetic deficits after having first determined that the patient is not a candidate for surgery.7,39

The framework proposes a step-by-step approach, beginning with the nose. The rationale for selecting the nose as the first step is its independence versus all other features. The Goode method26 was chosen for use in the assessment framework because, unlike the Crumley method,40 it does not incorporate measurement of the upper lip or other structures not related to the nose itself. The nasofrontal angle and tip projection are included because these metrics require that the nose has a certain height and projection that relates only to itself. Ensuring that the nose is adequately projected, therefore provides a foundation of adjusted angles and lines upon which the chin and lips can then be based. If the nose is not considered first then other standard lines, and resultant treatment plans, will erroneously be placed on structures that are going to change. This has the potential to create further profile imbalances. This concept is already established in the surgical rhinoplasty setting,2,28,29 with multiple works supporting the role of chin and lip assessment and intervention as adjuncts to rhinoplasty.41–48 Furthermore, a surgical algorithm has also been proposed in which the chin is assessed before the lips for attaining profile balance,44 with recent data supporting that surgical treatment of the upper lip (subnasal lip lift) without adjunctive rhinoplasty negatively impacts nasal aesthetics.49

Despite enthusiasm for assessing and treating the nose, and an increasing popularity in non-surgical rhinoplasty, use of dermal filler in the nose is not taught in some countries. This is primarily because it is recognized as a high-risk procedure due to the complex vasculature and vascular course variations in this area of the face.21 There is a need for training and education to ensure that only cosmetic injectors of the appropriate skill level perform this advanced procedure. Adequacy of practitioner experience in the area requiring projection, an understanding of the limits to which dermal filler can be used and when referral might be required are pivotal considerations. Readers are referred to the recent literature to obtain a thorough knowledge of pre-injection anatomic assessment (accounting for ethnicity were applicable), injection technique and appropriate product selection.7,17,18,20,21,50 Ideal candidates for non-surgical rhinoplasty include patients with mild cosmetic defects who would benefit from specific cartilage grafts if undergoing surgical rhinoplasty, including mild cases of deviation, dorsal convexity, dorsal concavity (e.g. in African and Asian patients), reduced tip projection or rotation, flat radix or minor irregularities after initial surgical intervention.7

Several factors limit the interpretation of our results. During the focus group discussion there was no disagreement about the key features (nose, chin, lips) that had been identified in the survey results and there was extensive discussion around which validated scales/assessment tools would be most suitable to incorporate into the framework and in which order. However the final components of the framework were not subject to formal voting, which may detract from its robustness. The work was not intended to provide validation of the framework, rather it pilot-tested the concept in a convenience sample of patients. Lack of pre-specified eligibility criteria introduces the possibility of selection bias and precludes formal analysis of the cases based on sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, gender, ethnicity and geographical location. The case providers submitted pre- and post-treatment photography to demonstrate that profile balance had been attained, but practitioners were not asked to repeat the profile assessment on their patients to quantify this objectively or to obtain post-treatment satisfaction metrics. Future formal evaluations of the assessment framework should take these limitations into account.

The proposed assessment framework provides a practical solution to profile assessment via stepwise approach to help facilitate overall balance in the relative contributions of the nose, chin, and lips. The contributors agreed that its use in the clinic enhanced their ability to assess their patients and better communicate the rationale for their proposed treatment plans. Although further formal validation may be warranted, initial real-world application of the assessment framework supports its use in the non-surgical clinic setting, demonstrating that, by first ensuring that the nose is balanced the chin and lips can then be brought into harmony.

The authors thank the co-chairs of the Scientific Exchange Working Group for their input into the early stages of this work, including the development and analysis of the practitioner survey. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the late Dr Neville Lee to the preliminary survey and the focus group discussion. The authors thank Hazel Palmer MSc, ISMPP CMPPTM of Scriptix Pty Ltd, for providing administrative support, professional writing assistance and editorial support in the preparation of this manuscript, which, in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines, was funded through an educational grant provided by Galderma Australia Pty Ltd.

*Scientific Exchange Working Group:

Steven Liew, Shape Clinic, Darlinghurst, NSW, Australia and St Vincent’s Private Hospital, Darlinghurst, NSW, Australia; Simone Doreian, Melbourne Aesthetic Medicine, Sandringham, VIC, Australia; Gregory Goodman, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia and University College of London, London, UK; Katherine Armour, The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia and Skin Health Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Frank Rosengaus, Facial Plastic Surgery, Ultimate Medica, México City, México; Kate Morlet-Brown, Maxillofacial Surgeon, Perth, WA, Australia

FR has received honoraria and consultant fees for lectures and support for conference attendance from Galderma outside of the current work. KMB has received honoraria and consultant fees for lectures and support for conference attendance from Galderma outside of the current work. CS has received honoraria and consultant fees for lectures and support for conference attendance from Galderma outside of the current work. JW has received honoraria and consultant fees for lectures and support for conference attendance from Galderma outside of the current work. TT is an employee of Galderma Australia Pty Ltd. MW, LC, HC, SJK, PP, AW and LKW declare no conflicts of interest.

©2023 Rosengaus, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.