Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9943

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 3

1Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

2Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Morningside-West, New York, NY, USA

3Department of Dermatology, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

Correspondence: Chidubem Okeke, Howard University College of Medicine, Department of Dermatology 520 W Street NW, Room 3035/3036, Washington, DC, USA

Received: August 15, 2023 | Published: August 23, 2023

Citation: Okeke CAV, Williams JP, Tran JH, et al. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and associated health outcomes among adults with skin cancer. J Dermat Cosmetol. 2023;7(3):91-97. DOI: 10.15406/jdc.2023.07.00243

Background: Ongoing investigations established the relationship between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and chronic diseases, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis. However, the specific association between ACEs and skin cancer remains relatively unexplored in scientific literature.

Objective: This study aimed to evaluate the relationship between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and measures of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among individuals with a skin cancer diagnosis.

Methods: Data from the 2019 Behavioral Risk Factors and Surveillance Study (BRFSS) were analyzed. The study included 418,268 adults, with 41,773 individuals diagnosed with skin cancer. HRQOL measures, including physical health, mental health, and lifestyle impairment, were assessed using self-reported data. ACEs were identified through participants' responses to 11 specific questions. Multivariable logistic regression analyses adjusted for demographic variables.

Results: Skin cancer survivors with a history of ACEs reported significantly poorer physical health (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.24-1.56) and mental health (OR 2.13, 95% CI 1.81-2.51) compared to those without ACEs. They also experienced higher levels of lifestyle impairment related to health (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.16-1.48). Commonly reported ACEs included parental separation, exposure to domestic violence, and verbal abuse.

Discussion: This study highlights the detrimental impact of childhood maltreatment on HRQOL among skin cancer survivors. Healthcare professionals should be attentive to the unique needs of this population by providing comprehensive support and interventions.

Conclusion: Childhood maltreatment has a significant negative impact on HRQOL among skin cancer survivors. The study emphasizes the importance of addressing the psychological and emotional well-being of individuals with a history of ACEs. Healthcare professionals should consider the specific needs of this vulnerable population to provide appropriate care and support. Further research is required to deepen our understanding of the underlying mechanisms and to develop effective interventions to improve the well-being of skin cancer survivors with a history of childhood maltreatment. Furthermore, longitudinal analyses and objective measures are needed to establish causal relationships and mitigate potential biases.

Keywords: ACEs, BRFSS, health outcomes, skin cancer, dermatology, quality of life, psychodermatology

ACE, adverse childhood experiences; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; BRFSS, behavioral risk factors and surveillance study; CDC, centers for disease control and prevention

Skin cancers are one of the most common cancers in the United States (US).1,2 Research has highlighted the detrimental effects of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on individuals' overall health and well-being throughout their lives. These experiences, such as abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction, have been linked to various chronic diseases, prompting ongoing investigations into their long-term impact, particularly concerning different forms of cancer.2,3

ACEs have been shown to be associated with the adoption of risky health behaviors in adulthood, such as smoking, alcohol use, and substance abuse.

These risk factors are directly associated with an increased risk of cancer development as well as worsened health outcomes.4,5Additionally, ACEs have been posited to have their own inherent influence on cancer development and survival.5,6 Research has shown that adults who have experienced ACEs have also been associated with lower serum levels of IL-2.6 As IL-2 is an immune modulator directly associated with preventing tumor progression, it has been hypothesized that these lower serum levels of IL-2 may be associated with the worse prognosis and survival seen in cancer patients who have experienced ACEs.5

While the correlation between ACEs and adverse health outcomes in adulthood is well-established, the specific association between ACEs and skin cancer remains relatively unexplored in scientific literature.

Therefore, this study aims to highlight the potential relationship between ACEs and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) measures among individuals diagnosed with skin cancer. By examining these factors, a more comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted impact of ACEs on skin cancer patients can be attained, potentially leading to improved care and support for this vulnerable population.

This cross-sectional study analyzed information from the Behavioral Risk Factors and Surveillance Study (BRFSS) dataset. The BRFSS is a nationwide health-related telephone survey administered to adults aged 18 years and older throughout the United States. Disseminated annually by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and state health departments, the BRFSS presents population level data regarding health-determining risk factors and behaviors, chronic disease prevalence, and utilization of preventative services. States participating in the BRFSS began collecting data on adverse childhood experiences starting in 2009. Iterative proportional fitting is applied to survey results to ensure the data is weighted appropriately and remains nationally representative. This continuously generated de-identified dataset is reviewed by an Institutional Review Board and is publicly accessible.

The BRFSS 2019 dataset includes measures of HRQOL such as physical health, mental health, lifestyle impairment, skin cancer prevalence, and measures of adverse experiences during childhood. Multiple studies have confirmed this questionnaire’s validity and reliability.7 Any participant who has received a positive diagnosis of skin cancer is presented as either having skin cancer (+) or not having skin cancer (-). Health status pertaining to physical health, mental health, and poor health contributing to lifestyle impairment was determined by asking about the number of days to which physical health, mental health, or poor physical health contributing to lifestyle impairment applied within the last the 30 days. Those who reported having 1-13 days or 14-30 days of poor physical health, poor mental health, or poor health contributing to lifestyle impairment were dichotomized as having “Good” or “Poor” health status respectively.

Responses to having ever experienced any number of the 11 ACEs presented were categorized as being participants “With” or “Without” a history of ACEs. Specific ACEs surveyed within this study are included in Table 1.

|

ACE Category |

Survey Question |

Response Option |

||

|

Household Issues |

||||

|

Mentally Ill Household Member |

Did you live with anyone who was depressed, mentally ill, or suicidal? |

Yes/No |

||

|

Substance Abuse in Household |

Did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic? |

Yes/No |

||

|

Did you live with anyone who used illegal street drugs or who abused prescription medications? |

Yes/No |

|||

|

Incarcerated Household Member |

Did you live with anyone who served time or was sentenced to serve time in a prison, jail, or other correctional facility |

Yes/No |

||

|

Parental Separation |

Were your parents separated or divorced? |

Yes/No |

||

|

Violence between Household Adults |

How often did you parents or adults in your home ever slap, hit, kick, punch, or beat each other up? |

Never/Once/More Than Once |

||

|

Childhood Abuse |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

Yes/No |

|

|

Physical Abuse |

Not including spanking, (before age 18), how often did a parent or adult in your home ever hit, beat, kick, or physically hurt you in any way? |

Never/Once/More Than Once |

||

|

Verbal Abuse |

How often did a parent or adult in your home ever swear at you, insult you, or put you down? |

Never/Once/More Than Once |

||

|

Sexual Abuse |

How often did anyone at least 5 years older than you or an adult, ever touch you sexually? |

Never/Once/More Than Once |

||

|

How often did anyone at least 5 years older than you or an adult, try to make you touch them sexually? |

Never/Once/More Than Once |

|||

|

|

How often did anyone at least 5 years older than you or an adult, force you to have sex? |

Never/Once/More Than Once |

||

Table 1

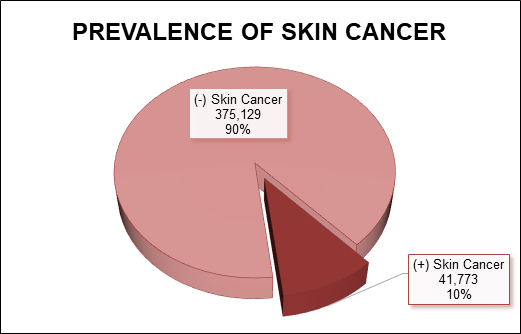

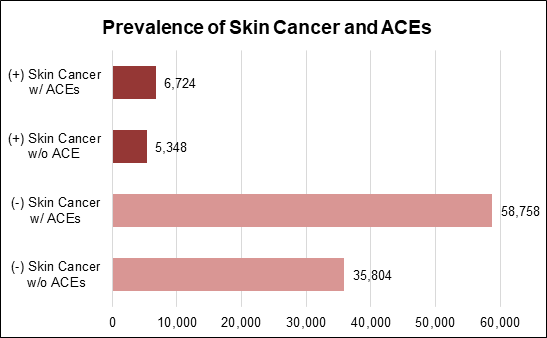

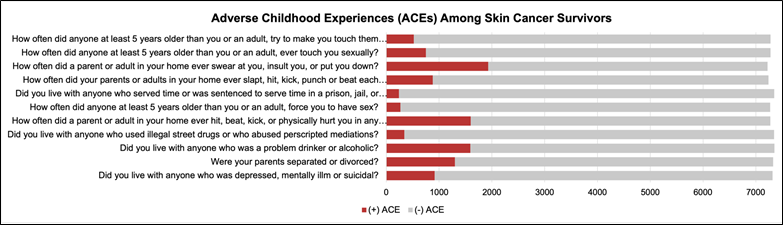

A total of 418,268 adults participated in the 2019 BRFSS survey. Of the sampled population, 41,773 individuals (10%) have received a diagnosis of skin cancer (Figure 1) 6,724 (56%) adult skin cancer survivors reported experiencing at least one ACE throughout their childhood (Figure 2). Among adult skin cancer survivors, the highest reported adverse experience during childhood was being sworn at, insulted, or put down (Figure 3). Demographic information regarding adult skin cancer survivors is presented (Table 2). Adult skin cancer survivors with any history of ACEs were predominantly over the age of 65-years-old (68%), female (54%), White and non-Hispanic (95%), overweight (38%), graduates of college/technical school (41%), and at an income level greater than or equal to $50,000 (50%) compared to skin cancer survivors without a history of ACEs. These individuals also more likely to have health insurance coverage (97%) compared to skin cancer survivors without a history of ACEs.

Figure 1 Prevalence of adult skin cancer survivors in sampled population. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2019.

Figure 2 Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among adults with and without diagnosis of skin cancer.

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2019.

Figure 3 Distribution of adult skin cancer survivors across measures of adverse childhood experiences.

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2019.

|

(+) Skin Cancer Total n (%) |

(+) Skin Cancer w/ ACEs n (%) |

(+) Skin Cancer w/o ACEs n (%) |

p-value |

|||||

|

Age |

< 0.0001 |

|||||||

|

18-24 years old |

30 (0.25) |

25 (0.37) |

5 (0.09) |

|||||

|

25-34 years old |

78 (0.65) |

54 (0.80) |

24 (0.45) |

|||||

|

35-44 years old |

226 (1.87) |

160 (2.38) |

66 (1.23) |

|||||

|

45-54 years old |

775 (6.42) |

520 (7.73) |

255 (32.90) |

|||||

|

55-64 years old |

2,231 (18.48) |

1,415 (21.04) |

816 (15.26) |

|||||

|

65+ years old |

8,732 (72.33) |

4,550 (67.67) |

4,182 (78.20) |

|||||

|

Sex |

0.062 |

|||||||

|

Male |

5,700 (47.22) |

3,124 (46.46) |

2,576 (48.17) |

|||||

|

Female |

6,372 (52.78) |

3,600 (53.54) |

2,772 (51.83) |

|||||

|

Race/Ethnicity |

< 0.0001 |

|||||||

|

White, Non-Hispanic |

11,609 (96.16) |

6,411 (95.35) |

5,198 (97.20) |

|||||

|

Black, Non-Hispanic |

90 (0.75) |

57 (0.85) |

33 (0.62) |

|||||

|

Asian, Non-Hispanic |

8 (0.07) |

4 (0.06) |

4 (0.07) |

|||||

|

American Indian/Alaskan Native, Non-Hispanic |

66 (0.55) |

40 (0.59) |

26 (0.49) |

|||||

|

Hispanic |

112 (0.93) |

78 (1.16) |

34 (0.64) |

|||||

|

Other Race |

187 (1.55) |

134 (1.99) |

53 (0.99) |

|||||

|

BMI |

< 0.0001 |

|||||||

|

Underweight |

201 (1.73) |

112 (1.73) |

89 (1.74) |

|||||

|

Normal Weight |

3,540 (30.53) |

1,890 (29.14) |

1,650 (32.30) |

|||||

|

Overweight |

4,450 (38.38) |

2,432 (37.50) |

2,018 (39.50) |

|||||

|

Obese |

3,404 (29.36) |

2,052 (31.64) |

1,352 (26.46) |

|||||

|

Education |

< 0.0001 |

|||||||

|

Did not graduate High School |

652 (5.42) |

428 (6.38) |

224 (4.20) |

|||||

|

Graduated High School |

3,054 (25.37) |

1,658 (24.72) |

1,396 (26.17) |

|||||

|

Attended College/Technical School |

3,286 (27.29) |

1,901 (28.35) |

1,385 (25.97) |

|||||

|

Graduated College/Technical School |

5,048 (41.93) |

2,719 (40.55) |

2,329 (43.66) |

|||||

|

Income |

< 0.0001 |

|||||||

|

< $15,000 |

667 (5.53) |

467 (8.25) |

200 (3.74) |

|||||

|

$15,000-24,999 |

1,477 (12.23) |

905 (15.99) |

572 (10.70) |

|||||

|

$25,000-34,999 |

1,095 (9.07) |

627 (11.08) |

468 (8.75) |

|||||

|

$35,000-49,999 |

1,530 (12.67) |

841 (14.86) |

689 (12.88) |

|||||

|

³ $50,000 |

5,098 (42.23) |

2,820 (49.82) |

2,278 (54.15) |

|||||

|

Health Insurance Coverage |

< 0.0001 |

|||||||

|

Yes |

11,785 (97.80) |

6,530 (97.22) |

5,255 (98.54) |

|||||

|

No |

265 (2.20) |

187 (2.78) |

78 (1.46) |

|||||

|

Physical Health |

< 0.0001 |

|||||||

|

Good (0-13d) |

9,451 (81.01) |

5,091 (78.17) |

4,360 (84.61) |

|||||

|

Poor (14-30d) |

2,215 (18.99) |

1,422 (21.83) |

793 (15.39) |

|||||

|

Mental Health |

< 0.0001 |

|||||||

|

Good (0-13d) |

10,585 (89.86) |

5,672 (86.50) |

4,913 (94.08) |

|||||

|

Poor (14-30d) |

1,194 (10.14) |

885 (13.50) |

309 (5.92) |

|||||

|

Poor health with lifestyle impairment |

< 0.0001 |

|||||||

|

Good (0-13d) |

4,996 (78.15) |

3,033 (76.44) |

1,963 (80.95) |

|||||

|

Poor (14-30d) |

1,397 (21.85) |

935 (23.85) |

462 (19.05) |

|||||

Table 2 Demographic characteristics among Adult Skin Cancer Survivors. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2019

Unadjusted bivariate analyses were conducted to evaluate the relationship between adult skin cancer survivors with any history of ACEs and measures of HRQOL including physical health, mental health, health status contributing to lifestyle activities impairment (Table 3). Adult skin cancer survivors had significantly higher odds of having poor physical health (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.40 - 1.69), poor mental health (OR 2.48, 95% CI 2.17 - 2.84), and poor health contributing to lifestyle activities impairment (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.16 - 1.48) compared to adult skin cancer survivors without a history of ACEs.

|

Odds Ratio (95% CI) (+) Skin Cancer |

p-value |

||

|

w/ ACEs |

w/o ACEs |

||

|

Physical Health |

1.54 (1.40, 1.69) |

reference |

< 0.0001 |

|

Mental Health |

2.48 (2.17, 2.84) |

reference |

< 0.0001 |

|

Poor Health with Lifestyle Impairment |

1.31 (1.16, 1.48) |

reference |

< 0.0001 |

Table 3 Associations between measures of physical health, mental health, and health contributing to lifestyle impairment among adult skin cancer survivors with and without a history of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2019

Multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to further evaluate the relationship between adult skin cancer survivors with any history of ACEs and measures of HRQOL after adjusting for demographic variables (Table 4). Adult skin cancer survivors with any history of ACEs had significantly higher odds of having poor physical health (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.24 - 1.56) and poor mental health (OR 2.13, 95% CI 1.81 - 2.51) compared to adult skin cancer survivors without a history of ACEs.

|

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

||||

|

Physical Health |

Mental Health |

Poor Health with Lifestyle Impairment |

||

|

ACE Exposure |

||||

|

No |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

|

|

Yes |

1.39 (1.24, 1.56)* |

2.13 (1.81, 2.51)* |

1.14 (0.98, 1.33) |

|

|

Age |

||||

|

18-24 years old |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

|

|

25-34 years old |

1.52 (0.28, 8.21) |

0.72 (0.25, 2.01) |

1.00 (0.22, 4.66) |

|

|

35-44 years old |

2.67 (0.57, 12.61) |

0.44 (0.17, 1.16) |

1.82 (0.46, 7.15) |

|

|

45-54 years old |

2.50 (0.55, 11.40) |

0.38 (0.15, 0.95)* |

1.58 (0.42, 5.93) |

|

|

55-64 years old |

2.85 (0.63, 12.83) |

0.24 (0.10, 0.59)* |

1.80 (0.49, 6.66) |

|

|

65+ years old |

2.61 (0.58, 11.73) |

0.13 (0.05, 0.32)* |

1.40 (0.38, 5.16) |

|

|

Sex |

||||

|

Male |

Reference |

Reference |

reference |

|

|

Female |

0.97 (0.87, 1.08) |

1.45 (1.25, 1.68)* |

0.87 (0.76, 1.01) |

|

|

Race/Ethnicity |

||||

|

White, Non-Hispanic |

Reference |

Reference |

reference |

|

|

Black, Non-Hispanic |

0.94 (0.51, 1.76) |

1.10 (0.56, 2.17) |

0.92 (0.45, 1.89) |

|

|

Asian, Non-Hispanic |

2.59 (0.42, 16.06) |

2.96 (0.31, 28.07) |

4.98 (0.77, 32.13) |

|

|

American Indian/Alaskan Native, Non-Hispanic |

1.92 (1.00, 3.68)* |

2.18 (1.07, 4.44)* |

0.88 (0.43, 1.81) |

|

|

Hispanic |

0.83 (0.48, 1.44) |

0.89 (0.48, 1.67) |

1.25 (0.70, 2.23) |

|

|

Other Race |

1.83 (1.25, 2.66)* |

2.43 (1.60, 3.69)* |

1.74 (1.12, 2.70)* |

|

|

BMI |

||||

|

Underweight |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

|

|

Normal Weight |

0.40 (0.27, 0.59) |

0.59 (0.36, 0.96)* |

0.43 (0.27, 0.69)* |

|

|

Overweight |

0.44 (0.30, 0.65) |

0.70 (0.43, 1.14) |

0.44 (0.28, 0.71)* |

|

|

Obese |

0.73 (0.49, 1.08) |

0.88 (0.54, 1.44) |

0.69 (0.43, 1.09) |

|

|

Education |

||||

|

Did not graduate High School |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

|

|

Graduated High School |

0.72 (0.57, 0.90)* |

0.83 (0.63, 1.10) |

0.75 (0.58, 0.98) |

|

|

Attended College/Technical School |

0.73 (0.58, 0.92)* |

0.92 (0.70, 1.22) |

0.76 (0.58, 1.00)* |

|

|

Graduated College/Technical School |

0.58 (0.46, 0.74) |

0.64 (0.47, 0.86)* |

0.57 (0.43, 0.75)* |

|

|

Income |

||||

|

< $15,000 |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

|

|

$15,000-24,999 |

0.65 (0.53, 0.80)* |

0.65 (0.51, 0.82)* |

0.61 (0.48, 0.77)* |

|

|

$25,000-34,999 |

0.47 (0.37, 0.58)* |

0.51 (0.39, 0.67)* |

0.48 (0.37, 0.63)* |

|

|

$35,000-49,999 |

0.30 (0.24, 0.37)* |

0.31 (0.24, 0.41)* |

0.33 (0.26, 0.44)* |

|

|

³ $50,000 |

0.19 (0.15, 0.23)* |

0.20 (0.16, 0.26)* |

0.25 (0.20, 0.32)* |

|

|

Health Insurance Coverage |

||||

|

No |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

|

|

Yes |

1.33 (0.91, 1.93) |

0.90 (0.62, 1.31) |

1.03 (0.67. 1.57) |

|

Table 4 Multivariate logistic regression evaluating the relationship between ACEs and measures of physical health, mental health, and health contributing to lifestyle impairment among adult skin cancer survivors

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2019 (*) Indicates a significant p-value <0.05

This study provides valuable insights into the impact of childhood maltreatment on HRQOL among skin cancer survivors. By examining a large, nationally representative sample, this study contributes to the existing literature by shedding light on an important, but understudied area. Our findings underscore the significant deleterious role of childhood maltreatment in influencing HRQOL outcomes among skin cancer survivors.

The first key finding of this study is that skin cancer survivors with a history of ACEs reported poorer physical and mental health outcomes compared to their counterparts without such experiences. This finding is consistent with prior research demonstrating the enduring effects of childhood maltreatment on various health outcomes throughout the lifespan. Researchers had previously found that ACEs were associated with an increased chance of development of obesity in adulthood8 as well as development of other chronic health conditions such as high blood pressure,9 diabetes,5,10 atopic dermatitis,11 and psoriasis.12 While a direct mechanism of association has not been determined for these conditions, different biological pathways have been proposed to explain this phenomenon. One pathway suggests that ACEs cause a change in epigenetic mechanisms to the immune system, which may ultimately predispose patients exposed to ACEs to illness as well as chronic inflammation.13-15

Another proposed pathway suggests that repeated ACEs may cause dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which causes cortisol to be disproportionately produced. This dysregulation in HPA axis and cortisol production may cause patients to respond inadequately to inflammation and stress, which predisposes patients to chronic inflammation, fatigue, infection, and neurological issues.16-20 Despite the inconclusive mechanism of association between ACEs and these biological findings, this study, along with previous research, highlights the long-lasting impact of ACEs on the well-being of individuals, even after they have survived skin cancer.

Furthermore, this study's inclusion of multiple HRQOL measures provides a comprehensive assessment of the overall well-being of skin cancer survivors with a history of childhood maltreatment. The findings indicate that these individuals not only experience poorer physical health but also suffer from compromised mental health and lifestyle impairment. These findings are consistent with previous studies that found that ACEs negatively affected the physical and mental development of patients who experienced ACEs.21 The effect of ACEs on physical health, mental health, and lifestyle impairment may have multiple proposed explanations. Patients with a history of multiple ACEs were often found to face barriers with educational success,22,23 health literacy,24 and poor reading ability.25

These barriers are negatively affecting a patient’s knowledge of and access to medical care, which results in delays in both diagnosis and treatment. This is also congruent with previous research that showed that education regarding skin cancer and health literacy can influence skin cancer prevention and treatment.26,27 Additionally, patients with a history of ACEs of neglect are predisposed to engaging in risky health behaviors such as smoking, alcohol use, illicit drug use, or unsafe sex practices.28-30

These behaviors put patients at increased risk of developing chronic health conditions such as obesity, hypertension, hypercholesteremia, as well as development of different types of cancer and can even development of mental health disorders.31,32 These behaviors may stem from neglect, where patients may not have been educated or prevented from engaging in these behaviors at an early age, or in homes where the adults engage in these behaviors themselves, research has shown that it can create a self-perpetuating generational cycle of ACEs.33-35 Ultimately, the present study highlights the multifaceted nature of the impact of childhood maltreatment on HRQOL and emphasizes the importance of addressing both the physical and psychological aspects of well-being in this population.

This knowledge of a patient’s developmental history becomes instrumental in ensuring better HRQOL outcomes for skin cancer survivors and ultimately calls for comprehensive, multidisciplinary, coordinated care for these patients. Healthcare professionals should also recognize the potential psychological and emotional challenges faced by individuals with a history of ACEs and skin cancer. A holistic approach to care, which considers the specific needs of this vulnerable population, is thus crucial. Regular communication and information-sharing between providers play a crucial role as this ensures that everyone involved is aware of the child's progress, any changes in their condition, and potential adjustments required in their treatment plan. Collaborative efforts can help identify any gaps in care, prevent misunderstandings, and promote a more streamlined and efficient healthcare journey for the developing patient. By being vigilant in screening for ACEs in both pediatric and adult patients and offering appropriate support and interventions, healthcare professionals can potentially prevent worse HRQOL outcomes in future skin cancer survivors and improve the overall well-being of skin cancer survivors who have experienced childhood maltreatment.

It is important to acknowledge that the cross-sectional design of this study limits the ability to establish causal relationships between childhood maltreatment and HRQOL outcomes. Future research utilizing longitudinal analyses could provide stronger evidence regarding the temporal associations between ACEs and HRQOL in skin cancer survivors. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of recall bias. Future studies could incorporate objective measures of childhood maltreatment, such as official records or reports, to enhance the reliability and validity of the findings. These methodological improvements would strengthen the evidence base and contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between childhood maltreatment and HRQOL among skin cancer survivors.

This study's findings regarding the detrimental impact of childhood maltreatment on HRQOL among skin cancer survivors in a nationally representative sample carry significant implications for clinical practice and public health. This study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on the long-term consequences of ACEs and emphasizes the need for comprehensive and tailored support for both individuals currently facing ACEs as well as individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment and skin cancer. Further research is warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms driving this relationship and to identify effective interventions that promote resilience and improve the well-being of this vulnerable population.

CAVO is the inaugural recipient of the Women’s Dermatologic Society-La Roche Posay Dermatology Fellowship. ASB is the inaugural recipient of the Skin of Color Society Career Development Award as well as the Society for Investigative Dermatology Freinkel Diversity Fellowship Award, and recipient of the Robert A. Winn Diversity in Clinical Trials Development Award, funded by Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation.

Authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

©2023 Okeke, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.