Journal of

eISSN: 2373-633X

Case Report Volume 8 Issue 4

1Department of Orthopaedics, Kalpana Chawla Government Medical College Hospital, India

2Department of Anaesthesia, Guru Nanak Medical College, India

3Senior Resident, Department of Orthopaedics ESI-PGIMSR, India

Correspondence: Mohit Jindal, Assistant Professor, Department of Orthopaedics, Kalpana Chawla Govt. Medical College Hospital, Karnal (Haryana), India, Tel 9891904545

Received: February 24, 2017 | Published: August 23, 2017

Citation: Jindal M, Garg K, Kumar N, et al. Large cystic intradural schwannoma extending from L2 to S4 spinal segments: a case report. J Cancer Prev Curr Res. 2017;8(4):299-302. DOI: 10.15406/jcpcr.2017.08.00283

Introduction: Schwannoma originates from the sheath of spinal cord roots - neurilemma or Schwann cells (so it is mainly called neurilemmoma or Schwannoma) and makes one third of primary spinal cord tumours.1-6 The tumour localization is in various parts of spinal cord, but prevails in cervical and thoracic, rare in lumbar and sacral regions.1-7 According to histological structure schwannoma is benign tumour, but growing in the narrow spinal canal makes a severe pathological situation: pain and later on the signs of spinal cord compression. Degenerative changes like haemorrhage, calcification, and fibrosis are commonly seen, but cystic changes are relatively rare.

Case report: A 27year old male patient resident of Tanzania came to us with presenting complaints of a radicular pain with weakness in the Left lower limb for the past 7years. The patient was however able to walk independently and able to negotiate his routine activities. Skiagram of lateral lumbar spine revealed scalloping of the vertebrae from L2 -S4 with widened central canal. MRI revealed a large T1 iso-intense and T2 variable intensity tumour with widened canal with largest canal diameters of 3.5cm at L5. Near total excision of the tumour was done. Histological investigation confirmed the diagnosis of cystic schwannoma with alternating hypercellular (Antoni A) and hypocellular (Antoni B) areas in a fibrillar background. The patient was asymptomatic after the surgery and neurology was not disturbed post op.

Keywords:lumbosacral region, nerve sheath neoplasms, neurilemmoma, spinal cord neoplasms

Schwannoma originates from the sheath of spinal cord roots neurilemma or Schwann cells (so it is mainly called neurilemmoma or Schwannoma) and makes one third of primary spinal cord tumours.1-6 The tumour localization is in various parts of spinal cord, but prevailsin cervical and thoracic, rare in lumbar and sacral regions.1-7 It can grow exophytic above and below the dura of spinal cord (extremely rare intramedullary) or involve the spinal root and interfere its fibres. According to histological structure schwannoma is a benign tumor, but growing in the narrow spinal canal may cause canal compromise resulting in cord compression and its squeal. Degenerative changes like haemorrhage, calcification, and fibrosis are commonly seen in schwannom as, but cystic changes are rare.

In November 2016, a 26-year-old man, resident of Tanzania presented with a 7year history of progressive lower back pain with radiation and weakness of the left lower limb. The patient was however, able to ambulate without support and able to do his routine activities independently. The patient sought medical consultation locally in Tanzania but was generally kept on analgesics alone. It was in July 2016 that a Skiagram was done followed by an MRI scan and a Biopsy from the lesion done at Tanzania, to arrive at the diagnosis and case referred to us for further management.

The pain in the lower back was aggravated by lying supine and walking, while relieved by sitting. He had no history of antecedent trauma or constitutional symptoms. Physical examination revealed no spinal tenderness, Normal range of motion with no paraspinal spasm and negative root tension signs. Motor Examination revealed weakness in Left Lower limb (Left Knee Flexion 4/5, Lt Ankle dorsiflexion, Plantar Flexion 4/5, EHL 4/5, FHL 4/5). Right lower limb was 5/5. There was no sensory deficit and all reflexes were present. A large cafe au lait lesion was seen in the upper back (Scapular Region Left side) (Figure 1) measuring about 10 X 10cm in size. However, no vision complaints, no other cutaneous manifestations were present suggestive of neurofibromatoses and fundus examination was normal.

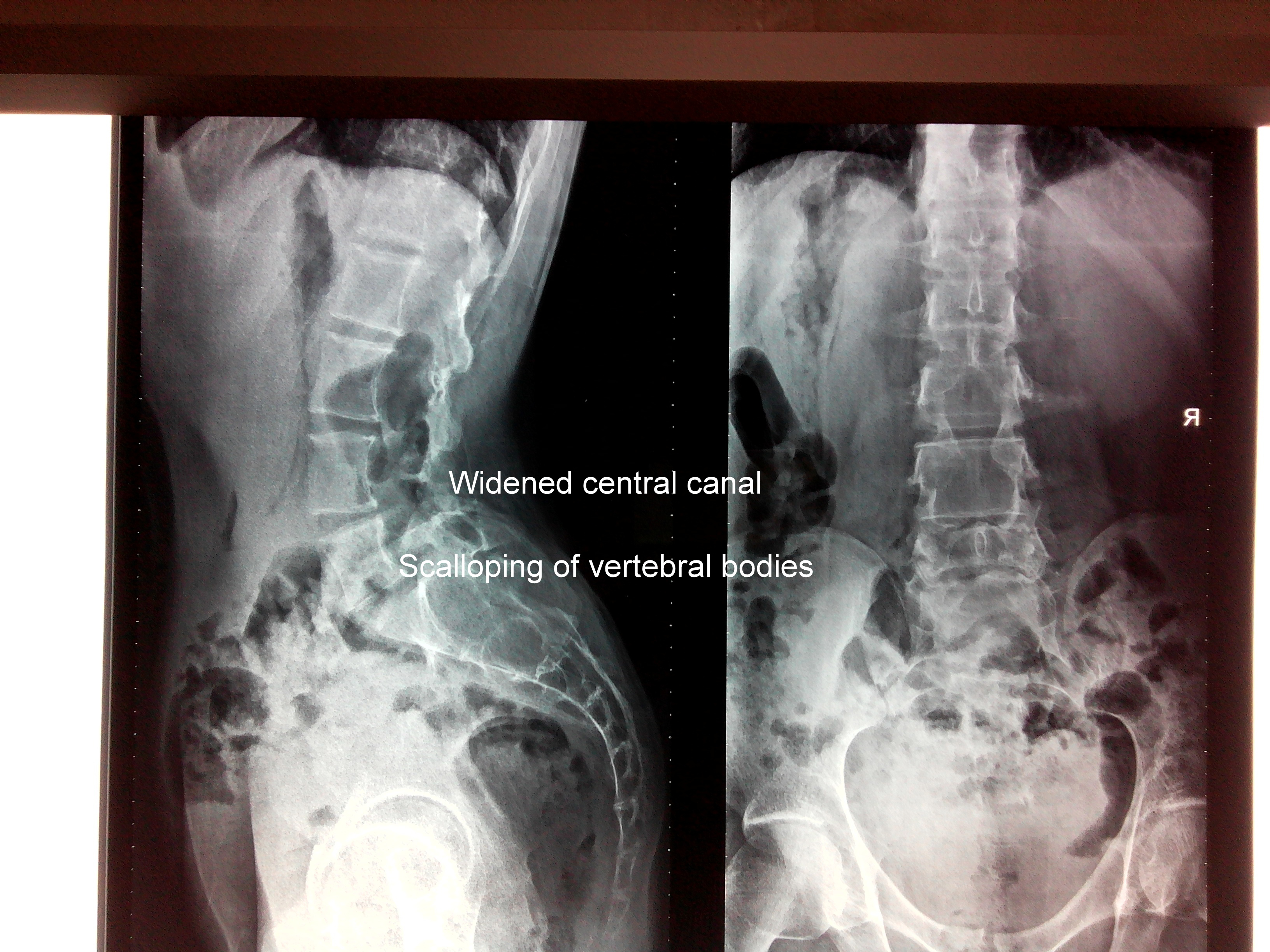

Lateral radiographs demonstrated scalloping of multiple lumbar and sacral vertebrae with widened central canal. The Patient underwent a biopsy from L4 - L5 level at Tanzania via partial laminectomy and the same can also be appreciated on the Lateral skiagram of Lumbar spine (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Showing Skiagram of Lumbar spine showing widening of the central canal with scalloping of the vertebral bodies.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large cystic lesion filling almost the entire spinal canal with anteriorly displaced filum terminale extending from L2 to S4 with septation, scalloping of the adjacent vertebral bodies with widened central canal with maximal canal widening at the level of L5 body measuring to the tune of 3.5 cm, and a iso-intense signal on T1- weighted images, but mixed signal on T2weighted images suggestive of septations (Figures 3 & 4). Gadolinium contrast caused heterogenous enhancement of the tumour (Figures 5 & 6) Bilateral laminectomy (L2 to S4) was performed using a posterior midline approach to expose the dura, which was found to be thinned out, tense, and without pulsation and every possible measures were taken to prevent postoperative instability. Under microscopic visualisation, a midline durotomy was performed and a well-defined, encapsulated, yellowish, soft, friable, cystic tumour was found loosely adherent to the arachnoid, displacing the roots anteriorly. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large cystic lesion filling almost the entire spinal canal with anteriorly displaced filum terminale extending from L2 to S4 with septation, scalloping of the adjacent vertebral bodies with widened central canal with maximal canal widening at the level of L5 body measuring to the tune of 3.5cm, and a iso-intense signal on T1- weighted images, but mixed signal on T2weighted images suggestive of septations (Figures 3 & 4). Gadolinium contrast caused heterogenous enhancement of the tumour (Figures 5 & 6) Bilateral laminectomy (L2 to S4) was performed using a posterior midline approach to expose the dura, which was found to be thinned out, tense, and without pulsation and every possible measures were taken to prevent postoperative instability. Under microscopic visualisation, a midline durotomy was performed and a well-defined, encapsulated, yellowish, soft, friable, cystic tumour was found loosely adherent to the arachnoid, displacing the roots anteriorly.

The tumour was easily separated from the dura. The tumour was dissected intact by cutting the vascular pedicle at S1 with bipolar cautery. Histopathological examination showed alternating hypercellular (Antoni A) and hypocellular (Antoni B) areas in a fibrillar background without any axons. There were numerous distended vascular sinusoids with peri-vascular haemosiderin laden macrophages. There was no evidence of nerve infiltration or mitoses to suggest malignancy. The diagnosis was cystic schwannoma. S-100 and CD-34 marker were used for analysis. The specimen was outsourced so the images are not available.

The patient had complete relief of symptoms after surgery and neurology remained intact post operatively. He was discharged on fifth day post operatively after the first dressing. On the 15th post-operative day, stitches were removed under aseptic conditions. The patient will be followed up for every 2months for first year for development of any symptoms or neurodeficit, repeat MRI will be done at the end of first year to see for the recurrence of the tumour. There were no psychological abnormalities observed with the patient before and after the operation.

Schwannomas are tumours arising from the embryonic neural crest cells of the nerve sheaths of peripheral and cranial nerves. The first case was reported in various names, including perineural fibroblastoma, neurilemmoma, neurinoma, neurilemoma, and peripheral glioma, have been used. In the spinal region, schwannomas have a predilection for sensory nerves and tend to arise from the dorsal roots.8 In a majority of cases, these tumours are solitary. However multiple schwannomas are seen in some rare cases like neurofibromatosis type 2, a genetic condition that is characterized by the formation of non-cancerous tumours that affect the nervous system; Schwannomatosis: It is a genetic condition that is a usually seen in adults and manifests as multiple schwannomas; Gorlin-Koutlas syndrome: A complex genetic disorder of multiple tumours in the body including multiple Schwannomas.

The tumours can occur in the peripheral nerves (arms and legs) and the spinal nerves; intracranial tumours occur in the head. Spinal Schwannomas are among the most common type of schwannomas and they occur from the nerves of the spinal cord; they constitute around one-third of the schwannomas. They are not usually associated with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2). Spinal Schwannoma is typically observed between the age ranges of 30-50 years. It is observed in young and middle-aged adults. Both males and females are equally affected in a majority of cases.9,10 However, against a background of neurofibromatosis type 2, the tumours may be observed with a higher incidence in females than males. Also, with respect to intracranial schwannomas, females are affected more than males.

Schwannomas have no known geographical, racial, or ethnic preference; they are seen worldwide. They are among the more common intradural spinal cord tumours in adults (i.e., occurring within the outermost brain and spinal cord membrane). However, sometimes they may be extending through the dural aperture as a dumbbell mass with both intradural and extradural components.11 Tumours arising in the cauda equina or around the conus medullaris can become larger than other spinal tumours because of the relative mobility of the roots and the wide diameter of the spinal canal.

Spinal Schwannoma may not present any signs and symptoms in some cases, and may be detected incidentally. In tumours with signs and symptoms, it may be dependent upon the location on the spine. Spinal Schwannomas are mostly observed in the cervical and lumbar region and may cause associated signs and symptoms. Pain from these tumours may be confined to the tumour site or spread across the region.

Lumbar plexus tumour can lead to weakness, numbness, walking difficulties, and severe shooting pain in the back, due to compression of the nerve.12,13 If the sacral plexus nerve of the lower back is affected, it can cause back pain, alteration in bowel movements and bowel control, alteration in urinary bladder control, etc. If the tumour occurs in the neck region at the base of the brain, it can compress the brainstem and cause breathing difficulties.

The initial symptoms are varied in accordance with the level of the tumour. The pain is localized in one (tumour) place, sometimes spread in both sides, mostly temporarily, but constantly in the same place and hurt as a knife. At the beginning the root pain is attributed to the disturbance of nerve conductivity because of the direct or indirect irritation of nerve root or root compression by the tumour. Later on when compression increases to spinal cord, spinal tracts gets damaged and myelopathy develops.14 However, motor weakness rarely occurs as an initial symptom in the lumbosacral region. Motor weakness of the lower extremity may not be obvious until the later stage, as in patients with lumbar canal stenosis.

Definitive diagnosis is based on histological analysis. Schwannoma in its classic form consists of spindle-shaped cells with pale, eosinophilic cytoplasm arranged in 2 characteristic patterns: Antoni A (compact, hypercellular, well-organised spindle cells in a palisading pattern) and Antoni B (hypocellular, loose-textured pleomorphic cells with predominantly myxoid cytoplasm).15 The hallmark histological feature of the schwannoma is the Verocay bodies.

Although schwannomas originate from nerve tissue, only 50% of cases have a direct relation with a nerve.16 Hence complete excision without sacrificing nerve roots is feasible in most of the contained non-invasive varieties. Increased vascularity in the sacral region can be tackled easily with intra-operative haemostasis when anticipated. Surgical treatment of cystic schwannomas can be very demanding because of the adhesion of the tumour capsule to the surrounding structures, fragile tumour capsules, and difficulty in identifying the arachnoidal planes. Early identification of the arachnoidal planes without opening of the cyst and sharp dissection may be useful. Complete excision without resultant neurological deficits may be feasible provided that there is no entrapment of nerve roots.

This case is unique in the sense that spinal schwannoma is found in relatively young patient of 26 years of age while the usual age of first manifestatation is in 4th or 5th decade.17.

The extent of the tumour from L2 to S4. Schwannomas are commonly found in lumbar and cervical region but the extent involving almost whole of the lumbo-sacral spine is rare.

Typically, a schwannoma is well encapsulated and solid when it is small, but may present cystic and necrotic changes in it when it is large.18 and so is found in this case.

None.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

©2017 Jindal, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.