Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4396

Research Article Volume 15 Issue 4

Department of Internal Medicine, University of California, USA

Correspondence: Ezra A. Amsterdam, MD, University of California, Davis, Medical Center, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, 4860 Y Street, Suite 2820, Sacramento, CA 95817, USA

Received: April 17, 2022 | Published: July 21, 2022

Citation: Sultanzai B, Amsterdam EA. Up is down, down is up: ectopic atrial bradycardia or junctional Rhythm? J Cardiol Curr Res. 2022;15(4):97-98. DOI: 10.15406/jccr.2022.15.00561

A 63-year-old man with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypertension presented to the emergency department (ED) with stabbing left anterior chest pain while he was sitting on a bench. The episode lasted 5-10 seconds. The patient has a history of atypical chest pain; he is dependent on alcohol, is an active smoker and abused cocaine in the past. He has no other known cardiac risk factors except male sex and age. Medications: albuterol, tiotropium, and flunisolide.

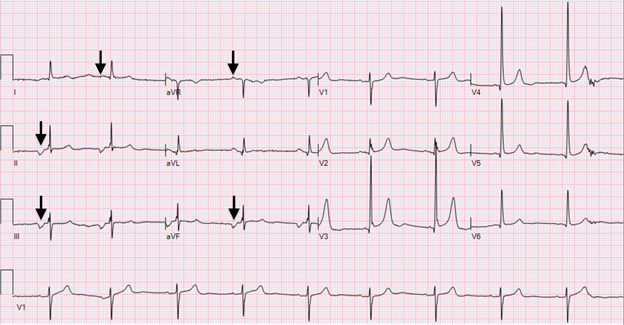

The patient’s electrocardiogram (ECG), (Figure 1) in the ED was computer interpreted as showing “ectopic atrial bradycardia” (EAB). There were also peaked T waves and ST elevations in leads V2-V4. The rhythm on the patient’s 13 ECGs between 2010 and 2017 was exclusively ectopic atrial bradycardia or ectopic atrial rhythm with rates ranging from 48 to 67/min with 1:1 atrioventricular conduction. Prominent T waves and ST elevations were also consistent in the precordial leads during these years. Except for one episode of syncope in 2010, the patient’s history does not include dizziness, lightheadedness, or falls.

Keywords: ectopic rhythm, junctional rhythm, chronic, atrial tachycardia

On examination in the ED the patient was afebrile, blood pressure 144/79mm Hg, pulse 64/min, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. There was no jugular venous distension, cardiac examination revealed a non-displaced point of maximal impulse, regular rhythm, and no murmurs or gallops. Chest examination was notable for bilateral rhonchi and occasional wheezes. There was no edema. Chest film showed the patient’s prior hyperinflation of the lungs. Transthoracic echocardiogram revealed left ventricular ejection fraction of 40%, mildly dilated left atrium, normal right atrium, and low normal right ventricular systolic function. Pertinent laboratory findings: serum conventional cardiac troponin I (<0.017ng/mL on two measurements; ref <0.04ng/mL), normal basic metabolic panel with serum potassium 3.9meq/L, normal thyroid stimulating hormone (1.62uIU/mL) and D-dimer (<150ng/mL; ref <285ng/mL). The patient was admitted to the medicine service for further evaluation.

The patient’s cardiac rhythm is either EAB or junctional rhythm based on inverted P waves in leads II, II, aVF and upright P waves in lead avR (Figure 1). Inverted P waves in the inferior leads and upright P in aVR indicate that atrial depolarization is proceeding in a retrograde fashion, suggesting that the site of the ectopic cardiac pacemaker is either low right or left atrium or atrioventricular junction. Inverted P waves could also result with an idioventricular rhythm in which there is retrograde depolarization of the atria but the QRS complex is not prolonged as would occur if the driving rhythm were in the ventricular His Purkinje system. In our patient’s rhythm, either an ectopic atrial focus or a focus in the atrioventricular junction has assumed cardiac pacemaker function because of sinus node failure. Potential factors for the patient’s sinus node impairment are his pulmonary disease, left ventricular dysfunction, and/or possible coronary artery disease.

Figure 1 The initial electrocardiogram demonstrated a heart rate of 57/min, isoelectric P waves in lead I (arrow), retrograde P waves in leads II, III, avF (arrows), upright P waves in lead aVR (arrow).

While the spontaneous rates of both EAB and junctional rhythm are in the range of 40-60/min, our patient’s normal PR interval (180ms) is also compatible with EAB or junctional rhythm. Although the ectopic focus in EAB is usually in the lower right atrium, this cannot be confirmed from the surface ECG.1 It is of interest that positive monophasic P waves in lead V1 have a sensitivity of 100% for a left atrial focus in ectopic atrial tachycardia.2

An innovative noninvasive approach for determining the site of the ectopic pacemaker in focal atrial tachycardia was developed by Kistler and colleagues.2 Based on P wave morphology in 8 ECG leads (I, II, III, aVL, aVR, V1, V3, V6), the algorithm correctly revealed the site of the ectopic atrial pacemaker in 93% of 30 patients, confirmed by electrophysiologic study. Assuming a similar relationship of P wave axis in EAB and ectopic atrial tachycardia, we applied the algorithm to our patient’s arrhythmia and determined that the ectopic focus was localized to the lower left atrium adjacent to the coronary sinus. The identifying factors in this localization were: near isoelectric P in lead I, negative P in leads II and III, and positive P in leads, aVL, aVR, V1, V3 and V6 (Figure 1). This correlation supports the diagnosis of EAB rather than junctional rhythm.

EAB is an uncommon rhythm as indicated by the paucity of literature on this topic and this case is one of the few reports on this arrhythmia.3 EAB is usually transient but in our patient, it appears to be chronic. The only rhythm that appears on his ECGs for almost a decade is EAB. EAB can occur in athletes due to high vagal tone; it can also be related to medications (e.g., beta blockers, rate-limiting calcium channel blockers, digoxin) or an underlying condition such as sinus node disease, pulmonary disease, ischemic heart disease, or electrolyte imbalance.1 The cause of this patient’s apparently chronic EAB is unclear but may be his pulmonary disease. Although we feel that the patient has chronic persistent EAB, this conclusion cannot be confirmed based on the available data.

The patient’s atypical chest pain resulted in a negative evaluation for an ischemic cardiac event that was associated with normal troponin levels and chronically stable ST segment and T wave changes. Hyperkalemia was excluded by the patient’s normal serum potassium levels. In this case, the computer was helpful in correctly interpreting the rhythm in contrast to a relatively frequent misinterpretation of arrhythmias by computer.4

If further evaluation of the patient’s EAB is considered necessary, ambulatory ECG monitoring would provide information on the degree of bradycardia, especially during sleep. In addition, it may reveal chronotropic incompetence. However, because the patient’s EAB has been asymptomatic for a prolonged period, his physician chose not to pursue further evaluation and was discharged from the ED.

None.

Author declare there are no conflicts of interest towards the manuscript.

Both authors had access to the data and a role in writing the manuscript.

None.

©2022 Sultanzai, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.