Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4396

Case Series Volume 18 Issue 1

1Heart Failure Unit, Adult Cardiology Department, Prince Sultan Cardiac Centre, Saudi Arabia

2Heart Failure Unit, Adult Cardiology Department, King Abdullah Medical City, Saudi Arabia

3Cardiovascular Prevention Unit, Adult Cardiology Department, Prince Sultan Cardiac Centre, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Abeer Bakhsh, King Abdullah Medical City, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

Received: January 20, 2025 | Published: February 4, 2025

Citation: Tamimi MA, Bakhsh A, AlAmro S, et al. The potential role of PCSK9 inhibitors in heart transplant patients: a case series. J Cardiol Curr Res. 2025;18(1):6-10. DOI: 10.15406/jccr.2025.18.00617

The Proprotein convertase subtilisin/ kexin type 9 inhibitors (PCSK9i) are a novel class of lipid-lowering agents that effectively reduce low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels. The use of these agents has expanded to involve recipients of solid organ transplants. Method: This case series reports the safety of using PCSK9i in three patients who received heart transplants, followed up for lipid profile, and observed the incidence of coronary artery vasculopathy (CAV) over two years post-treatment. Results: Evolocumab significantly reduced the LDL level without drug interaction with the immune suppression medication. The follow-up evaluation with coronary angiogram or myocardial perfusion images confirms the freedom from CAV incidence or progression. Conclusion: PCSK9i improved the LDL profile without any adverse effect related to the combined use of immune suppressive therapy. A lack of progression of CAV was observed through diagnostic imaging modalities, suggesting a potential preventive effect of evolocumab on CAV. However, large-scale, randomized, controlled trials are needed to confirm the efficacy of PCSK9i in lowering cholesterol levels, preventing CAV, and reducing the risk of graft rejection in heart transplant (HT) recipients.

Keywords: heart transplant, PCSK9 inhibitors, coronary artery vasculopathy, graft rejection

CAG, coronary angiogram; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; Q1/2/3/4, quartiles 1/2/3/4; DSA, donor specific antibody; PRA, panel reactive antibody; PCSK9i, proprotein convertase; subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors; LDL, low density lipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; TG, triglyceride; CAV, coronary artery vasculopathy; AMR, antibody mediated rejection; IHD, ischemic heart disease; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; HT, heart transplant; EF, ejection fraction; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; CMV, cytomegalovirus; MPI, myocardial perfusion imaging; PET, positron emission tomography; CK, creatine kinase; TFT, thyroid function tests; DSA, donor specific antibodies; AMR, antibody mediated rejection; CNI, calcineurin inhibitors; MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes

With significant advancements in immune suppressive therapies, heart transplantation is the gold standard treatment for end-stage heart failure (HF). However, cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV) affects the durability of graft function.1 This vascular complication is characterized by diffused concentric intimal hyperplasia and microvascular dysfunction.2 The incidence of CAV is 7.8% at 1 year and 50% at 10 years.3 Antibody-mediated rejection (AMR), cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, and accelerated coronary artery disease (CAD) due to atherosclerosis in the donor's heart are some of the complex elements contributing to CAV's etiology.4,5 The transplant guideline recommends CAV prevention through cardiovascular risk factors management, such as diabetes (DM), hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, and smoking.6 Statins have shown improved outcomes in heart transplant (HT) recipients.6,7

The HT recipients require tight lipid control; the target level for low-density lipoproteins (LDL) is <100mg/dl (<2.5 mmol/l) of HT.6 Immune suppressive medications can raise the risk of dyslipidemia, and they can also influence the development of CAV.7 Calcineurin inhibitors (CNI), specifically cyclosporine, are suspected of being responsible for the emergence of dyslipidemia.8,9 The drug-drug interactions of statine and immunosuppressive therapy can lead to myositis, rhabdomyolysis, and myalgias.10 Statins are the lipid-lowering therapy of choice; however, they present difficulties because they have significant drug-drug interaction when used with immunosuppressive treatments.6 PCSK9i provides a viable therapy, as they have been shown to significantly lower LDL levels and cardiovascular events in non-transplant populations.11

PCSK9i needs additional research in HT recipients due to their anti-inflammatory qualities and low risk of significant drug-drug interactions with immune suppressive treatments.7 PCSK9i use in post-HT patients has been the subject of observational studies and case series, consistently finding no increased risk of rejection, infection, or unfavorable medication interactions. More extended studies are necessary to determine the long-term advantages of PCSK9i in lowering CAV. The patients in this case series had uncontrolled dyslipidemia and were treated with PCSK9i after undergoing HT.12 This study aims to evaluate the effects of PCSK9i on lipid profiles and the progression of CAV in HT recipients.

This study aims to perform a case series analysis on three patients who received PCSK9i therapy after an HT. Its main goal is to evaluate the safety profile of PCSK9i in post-HT recipients, considering various clinical circumstances.

A retrospective case review was conducted on three post-HT patients who received PCSK9i. The study included a comprehensive review of the patient's medical history before transplantation. Furthermore, the relevant information on cardiovascular risk factors for donors was collected if available. Post-transplant examinations involved clinical, laboratory, serology, immunology, and imaging investigations, evaluating graft function. The study's biochemical investigation included lipid, liver, and kidney profiles. The study also examined the treatment plan's details, including lipid-lowering drugs and immune-suppressive therapy.

Case 1

A 56-year-old woman who underwent a HT in 1998. Her background history is consistent with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), nonischemic with no history of diabetes (DM), hypertension (HTN), or dyslipidemia. She underwent a heart transplant with an uneventful post-transplant clinical course. The cardiac donor data could not be retrieved. Currently, she is 26 years post-transplant on regular follow-up. She has developed dyslipidemia, HTN, and DM. Her current immune suppressive therapies are prednisolone 5 mg daily, mycophenolate mofetil 360 mg twice daily, and cyclosporine 150 mg twice daily. Her echocardiogram (ECHO) showed a normal left ventricle ejection fraction and no significant valve disease. Her lipid profile was consistent with a low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level of 2.29 mmol/L, a high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level of 1.06 mmol, and a triglyceride level (TG) of 1.79 mmol/L; other labs are shown in Table 1. She had a routine surveillance coronary angiogram in 2019 that showed significant disease in the left anterior descending artery (LAD) with 60 % focal stenosis and left circumflex disease with 70 % focal stenosis. She was diagnosed with coronary artery vasculopathy (CAV) grade 2 (Figure 1). Her immune suppressive therapy was adjusted to sirolimus 1mg daily instead of cyclosporine. She was further optimized for dyslipidemia management with atorvastatin 40 mg OD and ezetimibe 10 mg daily, in combination with evolocumab, to improve lipid control. Her insulin doses were adjusted to target a hemoglobin A1c of 7%. In addition, she continued on her single antiplatelet therapy with aspirin. On follow-up, her serum lipid levels significantly improved to LDL 0.93 mmol (Table 2). The repeated angiograms after 1 year of treatment did not reveal further progression of CAV (Figure 2). She later developed symptomatic anemia due to myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). The sirolimus was discontinued, and she was restarted on cyclosporin. She is currently on regular blood transfusions. Her cardiac graft function remains normal.

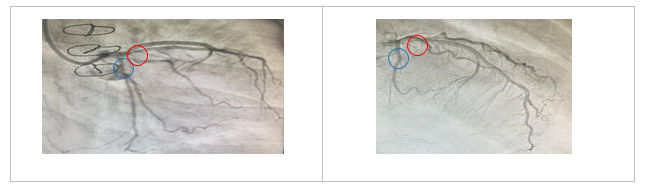

Figure 1 Coronary angiogram, right anterior oblique /caudal and left anterior oblique/cranial views of the left coronary system for Case I, respectively. There is a significant left anterior descending artery (Red circle) and left circumflex artery disease (Blue circle) before treatment with PCSK9 inhibitor

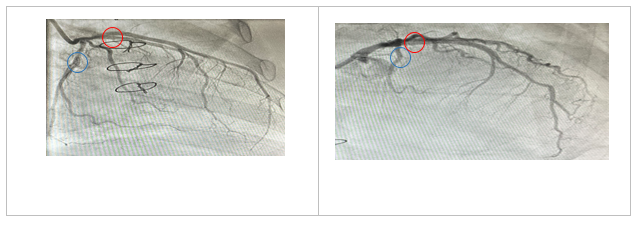

Figure 2 Coronary angiogram, right anterior oblique/caudal and left anterior oblique/cranial views of the left coronary system for Case I, respectively. The left anterior descending artery (Red circle) and left circumflex artery disease (Blue circle) post-treatment with PCSK9 inhibitor

Case 2

A 66-year-old man underwent HT in 2019. Had a significant history of ischemic heart disease (IHD), DM, HTN, dyslipidemia, and a coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery 15 years ago. He underwent an HT due to refractory angina and advanced heart failure. His immediate post-transplant course was uneventful. His donor was a 43-year-old male who died due to traumatic brain injury with normal left ventricular function, EF 65%, and no significant valvular heart diseases; no angiogram was performed for the donor’s heart. He has a routine follow-up in an outpatient setting; his surveillance endomyocardial biopsy showed no evidence of rejection. His follow-up panel reactive antibody (PRA) showed donor-specific antibody (DSA) in Class I, A33=1064 MFI, while class II antibodies were DQ7= 383 MFI. His immune suppressive therapies are mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily, tacrolimus 3 mg twice daily, and the prednisolone was stopped 12 months post-transplant. On follow-up, he had a high lipid profile of LDL 4.8 mmol/L, triglycerides 1.7 mmol/L, and HDL 1.14 mmol/L (Table 1). His dyslipidemia treatment included atorvastatin 20 mg due to muscular pain and ezetimibe 10 mg. 1-year post-transplant, a coronary angiogram showed a nonobstructive coronary artery with mild atherosclerosis. Diagnosis of CAV grade 1 was considered, and evolocumab 140 mg injection every 2 weeks was added to the patient's treatment regimen. His follow-up LDL is 0.93 mmol/L; other investigation is shown in Table 2. His graft function is normal; routine noninvasive CAV evaluation was unremarkable. However, he will be planned for a repeat angiogram.

|

|

Case 1 |

Case II |

Case III |

|

Lipid Profile LDL (mmol/L) TG (mmol/L) HDL (mmol/L) |

2.29 1.79 1.06 |

4.8 1.7 1.14 |

1.70 0.91 0.32 |

|

Liver Profile TB (umol/L) ALP (U/L) ALT (U/L) AST(U/L) |

7 95 13 16 |

10 95 17 22 |

13 172 17 14 |

|

Creatinine Kinase (U/L) |

60 |

69 |

52 |

|

Thyroid Function Test TSH (uIU/mL) T4 (pmol/L) |

3.14 16.7 |

2.06 16.9 |

0.99 15.8 |

Table 1 Pre-PCSK9i biomarker profile

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoproteins;TG, triglyceride; TB, total bilirubin; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; T4, thyroxine

Normal Values: ALP 35-104U/L, ALT35-52U/L, AST 2-37U/L; Creatinine Kinase <50U/L; HDL >1.9 mmol/L, LDL <2.5mmol/L, TG <1.7mmol/L, for females and > 1.6 mmol/L for males; TB 2-21umol/L, TSH 0.27-4.2uIU/mL, T4 12-22pmol/L

|

|

Case 1 |

Case II |

Case III |

|

Lipid Profile LDL (mmol/L) TG (mmol/L) HDL (mmol/L) |

0.93 0.94 1.26 |

0.98 0.97 1.69 |

1.2 1.47 2.08 |

|

Liver Profile TB (umol/L) ALP (U/L) ALT (U/L) AST(U/L) |

6 81 15 19 |

17 95 9 - |

3 67 13 - |

|

Creatinine Kinase (U/L) |

36 |

72 |

41 |

|

Thyroid Function Test TSH (uIU/mL) T4 (pmol/L) |

2.1 19.3 |

1.9 18.2 |

0.98 15 |

Table 2 Post PCSK9i biomarker profile

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoproteins;TG, triglyceride; TB, total bilirubin; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; T4, thyroxine

Normal Values: ALP 35-104U/L, ALT35-52U/L, AST 2-37U/L; Creatinine Kinase <50U/L; HDL >1.9 mmol/L, LDL <2.5mmol/L, TG <1.7mmol/L, for females and > 1.6 mmol/L for males; TB 2-21umol/L, TSH 0.27-4.2uIU/mL, T4 12-22pmol/L

Case 3

A 43-year-old woman underwent an HT in 2020. She had a history of treated brucellosis and DCM with recurrent polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. She underwent HT due to refractory VT and cardiogenic shock. The donor was a male donor who experienced an acute stroke and normal cardiac function, but no pre-transplant angiogram was available for the donor's heart. Immediately post-transplant, the patient experienced acute pancreatitis with pseudocyst and pancreatic hemorrhage. She had sepsis with disseminated fungal infection causing microabcesses in the liver and abdomen, with cultures showing aspergillosis infection. Her pancreatitis was presumed to be induced by tacrolimus. She was treated with an adjustment of immune suppressive, keeping the lowest required dose, and voriconazole. After the sepsis resolution, she was optimized on low-dose mycophenolate mofetil, 500mg bid, and cyclosporine 50mg bid. She had high total cholesterol and LDL levels, and she was started on Evolocumab (Table 1). At the 1-year follow-up, she had cytomegalovirus (CMV) viremia with a high viral load of > 2000 copies/ml, treated with valganciclovir. She also developed antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) a year after the transplant. The biopsy showed severe capillaritis and inflammatory infiltrate in the myocardium and the capillary blood; immune staining with c4d was positive. She was treated for AMR with plasmapheresis and a high-dose steroid. At the time of AMR, her PRA was elevated with Class 1 DSA A11= 2472 MFI, max level A11= 7426 MFI, and Class 2 DQ9 1443 with maximum level of DQ9 1559 MFI; serial monitoring is shown in Figure 4. Her current medications are prednisolone 5 mg daily, mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily, Cyclosporine 75 mg twice daily, Atorvastatin 40 mg daily, Ezetimibe 10 mg daily, and Evolocumab 140 mg twice per month. She underwent CAV evaluation 18 months after her HT through myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI), which did not reveal evidence of reduced coronary flow. A coronary angiogram was not performed due to difficulty in arterial access. Currently, she is clinically stable with routine outpatient follow-up.

The patient follow-up, which lasted from the end of 2019 to the end of 2023, entailed reviewing the charts of three post-HT patients with dyslipidemia and high LDL who had been treated with evolocumab for more than one year for the development of CAV.

Improvement of lipids profiles

The above patients were optimized by statins and ezetimibe as tolerated; despite that, they had uncontrolled lipid profiles. In addition, case II had a high risk of CAV based on his history of coronary disease and CABG, long-standing DM, and dyslipidemia. The introduction of evolocumab, a PCSK9i, resulted in a notable and clinically meaningful improvement in the lipid profiles of each patient. Significant reductions in LDL and triglyceride levels were consistently seen, indicating the effectiveness of the treatment in Table 2. The current improvement occurred without any significant adverse effects that could be linked to the evolocumab dosing. Evolocumab's safety profile is emphasized by the stability of creatine kinase (CK) levels, thyroid function tests (TFT), and liver panels, as shown by the data in Table 2.

Assessment of coronary artery vasculopathy (CAV)

The evaluation of CAV, a critical issue for patients who have had an HT, was carefully carried out by coronary angiography. The institute protocol consists of CAV evaluation invasive coronary angiogram at the end of 1st post-transplant year, then every 5 years. Non-invasive evaluation through MPI or PET is performed in between or if an invasive angiogram cannot be performed. Interestingly, none of the three patients showed CAV worsening through the available evaluation. Although Patient 1 had evidence of CAV grade 2 before starting evolocumab, careful adherence to the CAV protocol led to effective management, later confirmed by follow-up MPI and CAG tests showing no progression of CAV and no graft dysfunction.

Dynamics of immunological status

Donor-specific antibodies (DSA) against human leukocyte antigens (HLA) are responsible for AMR. The current state-of-the-art technology is measuring DSA in a semi-quantitative fashion (mean fluorescence intensity, MFI), and it has a high accuracy in predicting the risk of AMR. The burden of anti-HLA antibodies on a patient’s probability of finding a compatible transplant is defined by the panel reactive assay (PRA). Development of new DSA after HT indicates the risk of developing rejection or the presence of acute rejection. Patients had a PRA assay post-HT as per institution protocol. For the reported cases, PRA was performed before the use of evolocumab. Case 2 had PRA Class 1 positive with dynamic levels (A33=1064, A33=1795, A33=1795, and A33=713) shown in Figure 4. This did not translate into rejection based on endomyocardial biopsy. However, case 3 had PRA class II DSAs with (A11=2472, A11=4642, A11=6264, and A11=3110), which resulted in acute AMR (Figure 3).

Pathology insights

Rejection is the primary early complication of cardiac transplantation. Unfortunately, patients generally do not develop symptoms related to rejection until they have developed severe ventricular dysfunction. Therefore, endomyocardial biopsies are an essential component of post-transplant management. Endomyocardial biopsies are graded for cellular rejection according to the degree of inflammatory infiltrate, either diffused or focal, and the degree of myocardial and vessel involvement. Immune staining confirms the presence of antibodies fixation in the myocardium to diagnose AMR. Rejection leads to acute and chronic graft failure. Case 3, who had an AMR one year after heart transplantation that was related to her initial history of sepsis and aspergillosis infection, led to lower doses of immune suppression use. On the other hand, Patient 1 and 2 history was free of rejection.

In summary, our patients had a higher risk of CAV. Provided the presence of CAD risk factors in patients and the donor. In addition, case 3 had a history of CMV viremia and AMR, which are unique risk factors for future CAV development. Results support the safety and effectiveness of evolocumab in patients who have had heart transplants.

This case series investigates the safety and therapeutic potential of the PCSK9i evolocumab in three individuals who have received heart transplants and had uncontrolled dyslipidemia. All three patients consistently improved lipid profiles after evolocumab was added to statins. There are steady improvements in lipid profiles, LDL, and triglyceride levels without significant evolocumab-related adverse effects over two years of follow-up. The observations in our patients are similar to previous case reports on the use of PCSK9i in HT recipients. A case series of six HT recipients with uncontrolled lipid profiles showed a> 70% reduction in LDL levels.13 Another case series reported the safety of evolocumab use with calcineurin inhibitor CNIs in HT recipients, showing no drug interaction with CNIs over three months of use.14 Furthermore, a literature review revealed that 110 patients post-HT treated with alirocumab or evolocumab showed a sustained reduction of LDL from 40-87%. These findings support using PCSK9i for LDL reduction without drug interaction.12

Moreover, the lack of progression in coronary artery disease, as seen by coronary angiography or myocardial perfusion stress imaging, suggests a possible prevention against CAV. The effect of PCSK9i in stabilizing coronary plaque has been reported previously. This observation came from a study that evaluated 65 patients post-HT treated with PCSK9i for a median duration of 1.6 years. The follow-up CAV evaluation had proven stable coronary plaque, and no progression of CAV was observed by angiogram and intracoronary imaging.15 These observations support the benefit of PCSK9i in the HT population.

Randomized trials are needed to prove the effect of PCSK9i on lowering LDL levels and reducing the burden of CAV in heart transplantation recipients, thereby improving cardiac graft longevity.

None.

The authors don’t have any conflicts of interest.

©2025 Tamimi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.