Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4396

Review Article Volume 7 Issue 4

Assistant professor in Arabian Gulf University (AGU), Consultant Family Physician, Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Bahrain

Correspondence: Basem Abbas Al Ubaidi, Assistant professor in Arabian Gulf University (AGU), Consultant Family Physician, Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Bahrain

Received: October 25, 2016 | Published: December 16, 2016

Citation: Ubaidi BAA (2016) Missed Appendicitis in Primary Care: Lessons Learned. J Cardiol Curr Res 7(4): 00256. DOI: 10.15406/jccr.2016.07.00256

Abdominal pain is a common presenting symptom in primary care accounting for 10%, whilst a clinical diagnosis of acute appendicitis can be identified by thorough clinical examination,1 but still there are many diagnostic uncertainties in more challenging cases.2

Physician's overall diagnostic accuracy reaches up to 80% of traditional history, physical examination, and laboratory tests. The ease and accuracy of diagnosis depend on many factors such as age, sex, presence of gastritis symptoms, and presence of urological symptoms. While atypical acute appendicitis presentation, the physician should order abdominal ultrasonography (accuracy rates range 71 - 97%) and/ or computed tomography (CT) (accuracy rate range 93 and 98%).3 Failure or delay in diagnosis of acute appendicitis is a common malpractice complaint in primary care.

Unusual presentation of acute Appendicitis Cases in Primary Care

Case 1: 9 years old male child presented to primary care physician with epigastric pain, vomiting and loose motion of one hour duration after eating food from the restaurant. He was screaming from abdominal pain and can't stand still. He was afebrile and abdominal examination showed no rebound tenderness /rigidity. Urine R/M shows only positive ketone, CBCs was not done. The diagnosis was gastroenteritis and the patient showed some improvement after fluid and symptomatic treatment. The patient discharged home, and returned back with generalized abdominal pain, but more at right iliac fossa (RIF). While on abdominal examination revealed generalize abdominal tenderness, with positive RIF rebound tenderness. Further work was done with CBCs, ESR, C- reactive protein, abdominal X ray, ultrasound and CT scan revealed acute appendicitis with perforation. Laparotomy and peritoneal lavage were done for perforated appendix.

Case 2: 23 years old man presented to primary care physician with lower pelvic pain and mild urological symptoms with infrequent vomiting, the McBurney point was negative. The urine R/M showed pyurea and hematuria. But unfortunately, there was no response to urinary tract infection (UTI) treatment. The patient appeared next day with severe abdominal pain, mostly in right lower quadrant with positive rebound, obturator and psoas signs. Appendectomy was done and the patient showed dramatic improvement of symptoms and signs.

Case 3: 28 weeks pregnant lady presented to primary care physician with severe sharp unspecified pain, mostly in right upper and lower quadrant area, with frequent vomiting and anorexia. On examination was shown restless lady, and tense abdomen. She was referred as acute abdomen with probable diagnosis acute cholecystitis. Patient was admitted and ultrasound was suggesting acute appendicitis.

Case 4: 48 years old lady presented to primary care physician with severe abdominal pain which affect her gait. She complained nausea, restlessness, bad smell from her mouth. She had lower abdominal pain with rebound tenderness. The vaginal examination was an exacerbating abdominal pain with any cervix movement. She was referred as an acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID); but on further work up (US and CT scan) confirmed diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

Clinical presentation

Acute appendicitis diagnosis depends on a detailed history and the organized physical examination. Acute appendicitis can mimic the presentation of many surgical, medical, gynecological and urological emergency cases (Table 1).1,3,4

Alvarado score |

Variable Value |

Symptoms |

|

Migration |

1 |

Anorexia-acetone |

1 |

Nausea-vomiting |

1 |

Signs |

|

Tenderness in right lower quadrant |

2 |

Rebound pain |

1 |

Elevation of temperature C 37.3_ |

1 |

Laboratory |

|

Leukocytosis > 10.0 × 109/L |

2 |

Shift to the left > 75% |

1 |

Total* |

10 |

Table 1 Alvarado scoring scale for diagnosis of acute appendicitis.3

History: The history of acute appendicitis can go through many sequence (stages); first central colicky peri-umbilical abdominal pain (99%), followed by vomiting and pain migration (50%) to the right iliac fossa (RIF).5 The pain progression results from the nonspecific initial visceral pain to more localized parietal peritoneum pain.6 Associated symptoms include anorexia (24-99%), nausea (62-90%), infrequent vomiting (32-75%) to profuse vomiting (diffuse peritonitis), low grade fever (67-69%) and constipation.7 The clinical presentations of appendicitis depend mainly on the anatomical positions (retrocaecal /retrocolic, subcaecal/pelvic and pre/postileal) of their appendix location and anatomical surrounding structures (Table 2).1,3

MANTRELS score |

Variable Value |

M = Migration of pain to the RIF |

1 |

A = Anorexia |

1 |

N = Nausea and vomiting |

1 |

T = Tenderness in RIF |

2 |

R = Rebound pain |

1 |

E = Elevated temperature |

1 |

L = Leukocytosis |

2 |

S = Shift of WBCs to the left |

1 |

Total* |

10 |

Source: Alvarado.,19 |

Table 2 MANTRELS score for diagnosis of acute appendicitis.3

*Total score of 1- 4: Appendicitis unlikely; 5 – 6: Appendicitis possible; 7 – 8: Appendicitis probable; 9 – 10: Appendicitis very probable.

Examination: A physician should examine suspected cases of acute appendicitis thoroughly starting the general appearance, and do vital signs, inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation of abdominal sounds (Table 3).1,3 There are two important abdominal tests to diagnose a case of acute appendicitis are ; first coughing and second hopping test; by asking the patient either to cough or hop upward which exacerbates abdominal pain . The physician should also, notice any muscle guarding and rigidity in 21% of the cases, and if there is maximum tenderness over McBurneys' in 26% of the cases (Figure 1) which either verify by abdominal palpation or percussion (Figure 2).8,9 Physician should avoid rebound tenderness to avoid disturbing the patient. The physician should elicit the four most important signs to diagnosis a case of acute appendicitis (coughing, hopping test, percussion tenderness, and guarding / rigidity)10 with high positive likehood ratio (LR + 4.0).5

General Examination |

|

Flushed, a fetor or is, in pain, lie still, low grade fever and tachycardia |

|

Abdominal Examination Signs of localized/ generalized peritoneal irritation |

|

Dunphy’s sign |

Increased pain in the right lower quadrant with coughing |

Hip flexion sign |

Patient maintains hip flexion with knees drawn up for comfort |

Other peritoneal signs |

Rebound tenderness, hyperesthesia of the skin in the right lower quadrant |

Positive Hopping Test |

Increased pain in the right lower quadrant with hopping |

Positive Rebound Tenderness in McBurney’s Point |

Positive localized rebound tenderness on right lower quadrant and muscular guarding and Muscular Rigidity. |

Positive Percussion Tenderness |

Localized tenderness over percussion site at McBurney's point |

Normal Rectal or Vaginal examination |

RIF pain on rectal/ vaginal examination may indicate a pelvic appendix |

Positive Rovsing’s Sign |

RIF Pain on palpation left iliac fossa |

Positive Psoas’s Sign |

Pain on hyperextension of right thigh in lateral decubitus position (retroperitoneal retrocecal appendix) |

Pain thigh lifting against resistant in supine position (retroperitoneal retrocecal appendix) |

|

Positive Obturator’s Sign |

Pain on internal rotation of right thigh (pelvic appendix) |

Table 3 Complete examination of suspected cases of acute appendicitis

Figure 1 McBurneys' point which is approximately at two thirds of a line drawn from the umbilicus to the anterior superior iliac spine.64

Figure 2 McBurneys' point tenderness in RIF site.64

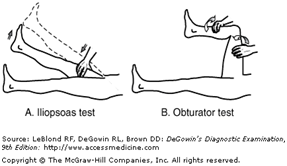

A physician should always perform a rectal or vaginal examination in acute abdomen; which is positive in pelvic appendicitis with Odds Ratio OR of 1.3.11 The physician should notice if there is pain in RIF when palpate LIF (Positive Rovsing’s Sign) (Figure 3).5,9 Ask patient to lie in supine position with flex right hip, then ask patient to lift the right thigh whereas physician applying pressure just above the knee (Figure 4) or the physician apply a passive extension of right leg at the right hip, while the patient posture has left lateral decubitus position (Positive Psoas Sign) (Figure 5 & 7).5,9 The physician can elicit a positive Obturator Sign by applying passive flex right knee with internal rotation the right hip (Figure 6 & 7).5,9

Figure 3 Positive Roving's Sign by palpate LIF exacerbate pain in RIF.64

Figure 5 Positive Psoas Sign with backward leg extension.64

Figure 6 Positive Obturator Sign by flex right knee with internal rotation of the right hip.64

Figure 7 Positive Psoas and Obturator Signs.64

Laboratory investigations

The presence or absence of inflammatory markers is either support or refute diagnosis of acute appendicitis such as, increase level of leucocyte/neutrophil/granulocyte and C-reactive protein (CRP).12˗15 Urine analysis and microscopy can either support or refute urinary tract infection, but it is confusing in pelvic acute appendicitis.16 Other important biochemical tests are serum/urine beta HCG, amylase, lipase, liver function tests, and electrolyte levels. Serum bilirubin is potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of acute perforated appendicitis.17 Other inflammatory markers of less importance are Interleukin-6; plasma D-lactate levels lactoferrin and calprotectin; have not been shown to aid the diagnosis of acute appendicitis or reduce unnecessary appendectomy.18˗20

Scoring systems

Sometimes, there are many difficult cases of acute appendicitis are missed in primary and secondary care. Moreover; there are many negative, unnecessary appendectomies (range 14 - 75%).21 Using clinical scoring systems (computer-aided diagnosis algorithm) to improve diagnosis of acute appendicitis based on symptoms, signs and laboratory findings. In suspected adult, use Alvarado Scores (AS),21 whereas, in suspected children use Pediatric Appendicitis Scores (PAS) or Samuel Scores (SS).22 It will increase the diagnostic accuracy up to 97.2%; also it is shown decrease in the number of appendicular perforations.23,24

Alvarado Score or MANTRELS Score1,3: It is simple scoring scales consist of three symptoms, three signs and two inflammatory laboratory markers (Table 4) or by using the mnemonic MANTRELS. The total score is 10; therefore, a score of 5 - 6 is low compatible (required observation), then score of 7 - 8 (proceed to radiological investigation) indicating probable, however, score of 9 – 10 (proceed to surgery) indicating a very probable acute appendicitis. The two most important symptoms with high positive likelihood ratio (LR+) are a history of RIF pain (LR += 8.0, 95% CI 7.3–8.5) and positive pain migration (LR += 3.1, 95% CI 2.4–4.2) (LR + 2.1, 95% CI 1.6–2.6).5,10 While, anorexia, nausea and vomiting are not alter the LR + of acute appendicitis, whereas, decreased LK with a history of similar previous pain (LR -= 0.3, 95% CI 0.2–0.4) and with the absence of right lower quadrant pain (LR -= 0.2, 95% CI 0.0–0.3). There are two ways of measurement of scoring scales depend on clinical (signs plus symptoms) and laboratory findings (Table 4: Alvarado and Table 5: Modified Alvarado (MANTRELS) Scoring Scales).

Alvarado score |

Variable Value |

Symptoms |

|

Migration |

1 |

Anorexia-acetone |

1 |

Nausea-vomiting |

1 |

Signs |

|

Tenderness in right lower quadrant |

2 |

Rebound pain |

1 |

Elevation of temperature C 37.3_ |

1 |

Laboratory |

|

Leukocytosis > 10.0 × 109/L |

2 |

Shift to the left > 75% |

1 |

Total* |

10 |

Table 4 Alvarado scoring scale for diagnosis of acute appendicitis.3

MANTRELS score |

Variable Value |

M = Migration of pain to the RIF |

1 |

A = Anorexia |

1 |

N = Nausea and vomiting |

1 |

T = Tenderness in RIF |

2 |

R = Rebound pain |

1 |

E = Elevated temperature |

1 |

L = Leukocytosis |

2 |

S = Shift of WBCs to the left |

1 |

Total* |

10 |

Source: Alvarado.,19 |

Table 5 MANTRELS score for diagnosis of acute appendicitis.3

*— Total score of 1- 4: Appendicitis unlikely; 5 – 6: Appendicitis possible; 7 – 8: Appendicitis probable; 9 – 10: Appendicitis very probable.

Other Scoring Systems: The use of Tzanakis Scoring System combined with ultrasound scanning along with clinical and laboratory findings (Ultrasound positive for acute appendicitis, tenderness in the right lower quadrant, rebound tenderness and a leukocyte count ≥12,000/L); aid physician for early diagnosis of appendicitis.20 The use of eight independent predictive variables in Appendicitis Inflammatory Response Score (AIRS) (right lower quadrant pain, rebound tenderness, muscular defense, WBC count, proportion of neutrophils, CRP, body temperature and vomiting) with high Sensitivity (0.97 vs. 0.92), and Specificity (0.93 vs. 0.88) to diagnose appendicitis cases.25 The use of seven independent predictive variables in Ohmann score (right lower quadrant pain, rebound tenderness, no micturition difficulties, steady pain, leukocyte count ≥ 10.0, age ≤ 50 years, and positive abdominal rigidity).26 The predictive symptoms and signs to diagnosis appendicitis in children by using Lintula score (gender, intensity of pain, relocation of pain, vomiting, pain in the right lower quadrant, fever, guarding, bowel sounds and rebound tenderness); which subsequently been validated in adults.27,28 The Fenyo-Lindberg scoring system uses nine clinical and one laboratory variable to form a score to predict cases of appendicitis.29

Pediatric Appendicitis Score (PAS) (Samuel score): The use of eight independent predictive variables in The Pediatric Appendicitis Score (PAS) (Cough/percussion/hoping tenderness in the RIF, anorexia, pyrexia, nausea and emesis, tenderness over the right iliac fossa, leukocytosis, polymorph nuclear neutrophil and migration of pain), the score are of sensitivity of 1, specificity of 0.92, positive predicted value (PPV) of 0.96 and negative predictive value (NPV) of 0.99.22 It is useful in stratifying the clinical risk of children with acute appendicitis by categorizing them as low (< 2), while in medium (3-6) need for further radiological examination (ultrasound or computed tomography) or need for a period of further evaluation, however high risk (≥7) of acute appendicitis,30˗33 while those with an Alvarado score between 3 and 6 should undergo a CT scan of the abdomen (sensitivity of 90.4% and specificity of 95%).32,33 None of the scoring systems definitive diagnose acute appendicitis or predict the need for further investigation. Therefore, clinical examination combined with clinical decision and using scoring scales will guide physicians for further investigation in unclear acute appendicitis.

Difficult diagnostic cases

Extreme of age: Listless infant and confused elderly may present with atypical signs and symptoms of acute appendicitis. So, the physician needs a high index of suspicion in examination of suspected appendicitis in this category.36

Appendicitis in children: While acute appendicitis is very common childhood abdominal operation,37 but diagnosis of appendicitis in ambulatory care was reaching only 2.3%38 because it remained a challenge for many clinicians.39 Early diagnosis of appendicitis will ultimately decrease appendicular perforation,6,17 abscess, gangrene, peritonitis and a shortening period of post-operative hospitalization.40,41 Usually, there was a delay in diagnosis of acute appendicitis in children42 due to misdiagnosis.43,44 Misdiagnosis rate was ranging from 7.5% to 37% for children 45 and the reason of misdiagnosis was either acute gastritis or gastroenteritis.46 The common age incidence of childhood appendicitis is mostly at 9-12years,47 and the red flag of acute appendicitis in childhood are vomiting,48 leukocytosis, high C-reactive protein level49 right lower quadrant tenderness.50,51 A high level of clinical suspicion; may need further investigation by either, abdominal ultra-sonographers (sensitivities range from 85% -90% and specificities range from 95% -100%) and CT scan which increase diagnostic accuracy and decrease negative laparotomy.51

Appendicitis wit urological symptoms: While one third of acute appendicitis may have urological manifested (e.g. right flank pain and dysuria, pyurea > 10 cells per high-power field) due to abnormal pelvic and retrocecal appendix positions.52

Appendicitis in Pregnancy: Usually, a typical appearance of appendicitis is present mostly during late pregnancy; because of appendix displacement from gravid uterus. The common complaints are nausea and vomiting with unspecified tenderness located on the right side of the abdomen (Right lower quadrant pain or mid or even upper right side of the abdomen) is the most common symptom. Acute appendicitis is common during pregnancy with an incidence of 0.15–2.1 per 1,000 pregnancies. Early use of either magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or abdominal ultrasound (US) will increase diagnostic accuracy of acute appendicitis in pregnancy and prevent both maternal (1–4%) and fetal (1.5–35%) mortality associated with perforation, which may occur more mostly in the third trimester.53-61 Missed appendicitis in pregnancy is common in primary care because of unusual presentation (e.g. heartburn, bowel irregularity, flatulence, malaise, or diarrhea, urinary frequency, dysuria or tenesmus and diarrhea).59

Appendicitis in women of child bearing age: Moreover, Pelvic pain of women is challenging scenario because of the long list of differential diagnoses ranged from lifesaving condition (e.g., ectopic pregnancy, appendicitis, ruptured ovarian cyst) to fertility-threatening conditions (e.g., pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion) must be considered.62,63 To increase accuracy of early diagnosis of appendicitis and decrease the rate of negative histopathology of appendectomy, we need to identify clinical scoring systems, laboratory and diagnostic imaging.21˗29

Appendicular abscess/ Appendicular mass: The physician should palpate abdomen for a tender mass at RIF in patient with swinging pyrexia with leukocytosis. The diagnosis was confirmed by either abdominal US or CT scans.64

The diagnosis of acute appendicitis needs good history, thorough examination and basic laboratory study and the requisite high index of suspicion. The scoring scale systems will enhance clinical judgment and increase acute appendicitis diagnostic accuracy.

None.

None.

None.

©2016 Ubaidi. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.