Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4396

Research Article Volume 1 Issue 5

1Specialty Registrar, Royal Victoria Infirmary, United Kingdom

2All India Institute of Medical Sciences, India

Correspondence: Bhaskar Dutta, Specialty Registrar, Northern Deanery, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 4LP, United Kingdom, Tel 44-7729963759, Fax 44-1733-678533

Received: July 23, 2014 | Published: October 28, 2014

Citation: Dutta B, Garg R, Trikha A, Rewari V (2014) A Prospective Audit on Outcome of Cardiac Arrests at a Tertiary Care Referral Institute. J Cardiol Curr Res 1(5): 00027. DOI: 10.15406/jccr.2014.01.00027

Introduction: A prospective survey of cardiopulmonary resuscitation following cardiac arrest was carried out over one year with the aim of identifying parameters related to outcome of cardiac arrest.

Methods: The resuscitation teams were provided with a proforma, which they had to fill up following an attempt to resuscitate an arrest victim. The resuscitation team comprised of a consultant and either two or three residents along with two nurses and one technical assistant. Patients were admitted to the Intensive Care Unit or a high dependency area under the department of anesthesiology and critical care, following successful resuscitation.

Results: A total of 102 numbers of cardiac arrests were treated by the residents of the department and 7 of these patients survived to leave hospital. The cardiac rhythm most frequently observed was asystole (40 cases), followed by ventricular fibrillation (VF) (36 cases) and pulse less ventricular tachycardia (VT) (18 cases). The least observed rhythm was pulse less electrical activity (PEA) (8 cases). Among all these rhythms, the revival rate was highest in patients with VF (26 cases, 72).

Conclusion: In conclusion, survival from cardiac arrest depends on a series of critical interventions. There are additional variables which modify the outcome, the most important being the interval between ‘arrest to initiation of CPR’ and ‘arrest to defibrillation’. Patients who developed ventricular fibrillation or tachycardia were more likely to survive than patients who developed asystole.

Keywords: cardiac arrest, resuscitation, survival

CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ECC, emergency cardiovascular care; AIIMS, all India institute of medical sciences; RR, recovery rooms; HDUs: High Dependency Units; OPD, outpatient department; GCS, glasgow coma scale

The roots of resuscitation extend back centuries, with a gradual course of evolution. But the basic techniques of modern cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) have been established since 1960 when Kouwenhoven, Jude and Knickerbocker described closed-chest cardiac massage.1 during the past 50years there have been many advances in the field of emergency cardiovascular care (ECC) based on new evidences. Most hospitals worldwide now have cardiac arrest teams and early intervention by a medical emergency team has been shown to significantly reduce the incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrest in hospital.2 There have been many studies on CPR which have reported on outcome, factors which affect outcome, and whether one could predict outcome.3–5 But despite the availability of such teams and advances in cardiopulmonary resuscitation the risk of death from such an event has remained largely static at 5080%.6–8

Poor survivability rates following CPR, and survival to discharge depends on a number of factors: location of arrest; whether witnessed or unwitnessed; ‘down time’ to defibrillation (if ventricular fibrillation/pulse less ventricular tachycardia); and co-morbidity (e.g. hypotension, sepsis, malignancy, acute stroke, pneumonia, organ failure etc).8 We have carried out a prospective audit on in-hospital cardiac arrest victims at our hospital, with the aim of identifying the shortcomings and devising the best feasible solutions for the improvement of survival rates.

This was a prospective study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation techniques and outcomes following cardiac arrest at various wards, high dependency and intensive care units (ICU) of main hospital at All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi from January 2009 to December 2009.9 were taken as the standard technique for resuscitation of the arrest victims.

At our institute, resident doctors are available round the clock in hospital. Any arrest at different places of hospital e.g. hospital wards, recovery rooms (RR), high dependency units (HDUs), outpatient department (OPD), casualty etc, is informed to Anesthesiology resident telephonically (mobile), who attends the case immediately. The resuscitation team comprised of a consultant (on duty) and either two or three residents along with two nurses and one technical assistant. All the residents who participated in the audit had two to three years of experience following completion of his/her post graduation in anesthesiology. The teams were provided with a proforma (includes rhythm, revival, witnessed or not, probable etiology, place, defibrillation), which they had to fill up following an attempt to resuscitate an arrest victim. Cardiac arrest was defined by the absence of a detectable pulse (“pulselessness”), by the patient’s unresponsiveness or by any arrest rhythms noticed on monitors. For asystole, flat line protocol (checking of leads and monitor, increase of gain) was followed. Resuscitation was deemed successful if a stable circulation was established and the resuscitation team disbanded.4 immediate survival was defined as the restoration of normal circulation for>20minutes. Each patient’s initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was recorded immediately after successful CPR (i.e. following immediate survival). The outcomes of interest were immediate survival after CPR and survival to hospital discharge. Patients were admitted to the ICU or a high dependency area under the department of anesthesiology and critical care, AIIMS, following successful CPR. If any patient required more than one episode of CPR during one stay in hospital, only the initial effort was examined. A subsequent arrest, if unsuccessfully treated, was recorded as a later death.

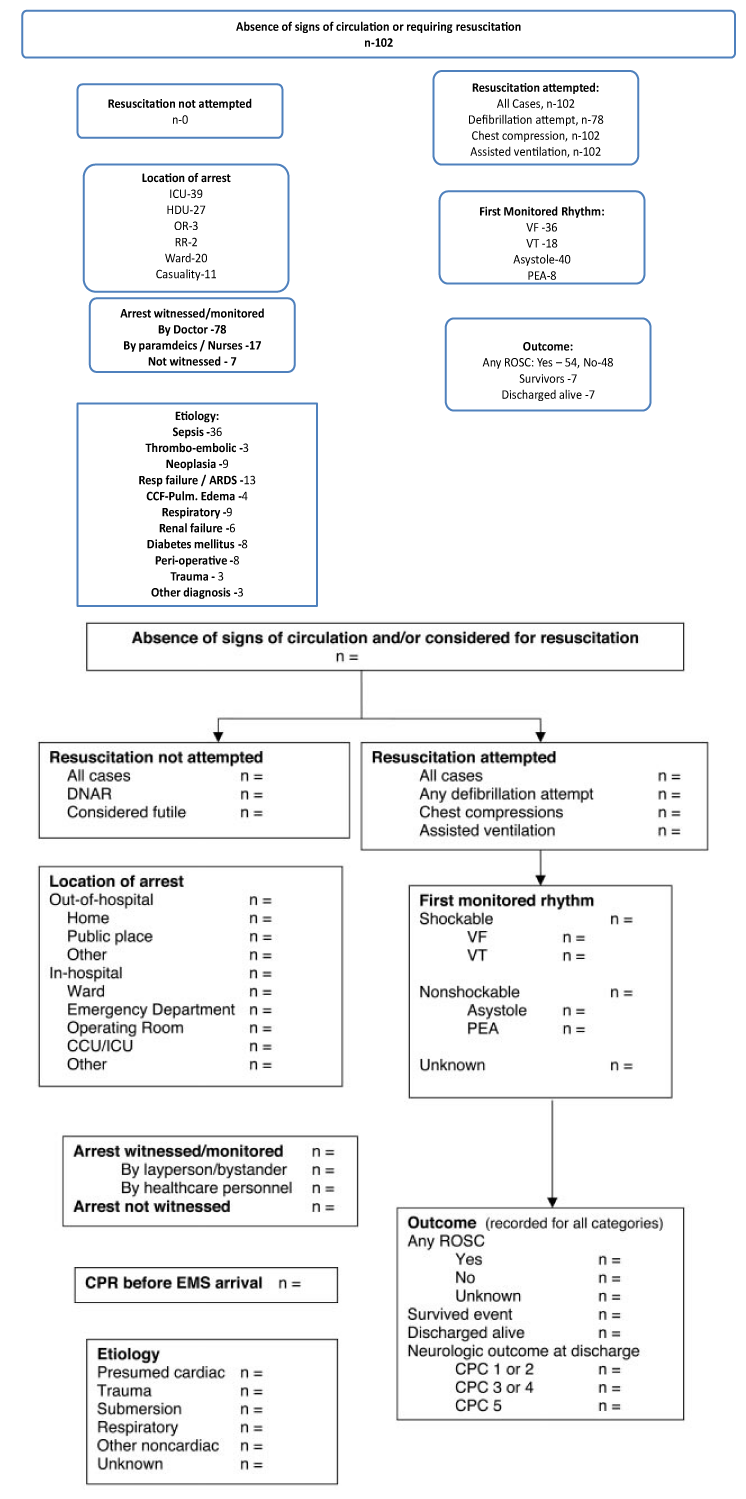

Our results depict the analysis of those cardiac arrests, which were managed only by the emergency duty team from the Department of Anesthesiology, and do not represent those of the entire hospital. The total number of cardiac arrests managed in the twelve months was 102 (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the outcome of CPR in these patients. All revived arrests were witnessed. Resuscitation was successful in 54 patients (52.9%). From these, 37(68.2%) died within 24hours, and 10(18.5%) died later. Seven patients left hospital, representing 6.9% of all arrests or 12.9% of the initial survivors.

Figure 1 The various parameters and outcome of cardiac arrest. ICU, intensive care unit; HDU, high dependency unit; OR, operating room; RR, Recovery Room (postoperative); CCF, congestive cardiac failure.

|

Total(n-102) |

Revived(n-54) |

Discharged(n-7) |

|

|

Gender- Male: Female |

52:50:00 |

28:26:00 |

4:03 |

|

Witnessed |

95 |

54 |

7 |

|

Witnessed by Doctors |

78 |

50 |

6 |

|

Witnessed by Paramedics/Nurses |

17 |

4 |

1 |

|

Etiology |

|||

|

Sepsis |

36 |

13 |

0 |

|

Thrombo-embolic |

3 |

2 |

0 |

|

Neoplasia |

9 |

4 |

0 |

|

Resp Failure/ARDS |

13 |

6 |

1 |

|

CCF-Pulm Edema |

4 |

3 |

0 |

|

COAD |

9 |

8 |

1 |

|

Renal Failure |

6 |

3 |

0 |

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

8 |

5 |

1 |

|

Peri-operative |

8 |

7 |

4 |

|

Trauma |

3 |

1 |

0 |

|

Other Diagnosis |

3 |

2 |

0 |

Table 1 Showing Outcome of CPR. ARDS, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome; CCF, congestive cardiac failure; COAD, chronic obstructive airway disease

Table 2 shows the sites of the cardiac arrests and the percentage of revival. It could be seen that, highest percentage of revival was inside the operation theatres (OT) (100%) and least in the ICU (38.5%). A total of 45 patients were defibrillated early (Table 3) i.e. within 3minutes, and all of them were revived. There were two patients who did not require defibrillation and were revived. These two patients were managed in the OT and were eventually discharged home. Table 1 shows the patients divided into different disease categories, with the number of initial survivors and the number who left hospital in each category. The maximum number of cardiac arrest patients was diagnosed with sepsis/septic shock (36 cases, 35.3%).

|

Site of Arrest |

No. |

Revived |

Discharged |

|

ICU |

39 |

15(38.5%) |

0 |

|

HDU |

27 |

18(66.7%) |

2 |

|

OT |

3 |

3(100%) |

3 |

|

RR |

2 |

1(50%) |

1 |

|

Ward |

20 |

9(45%) |

0 |

|

Casualty |

11 |

8(72.7%) |

1 |

|

Total |

102 |

54(52.9%) |

7(12.9% of all revived; 6.9% of all cardiac arrests) |

Table 2 Showing site of cardiac arrests and the outcome. ICU, intensive care unit; HDU, high dependency unit; OT, operation theatre; RR, recovery room

|

Total No. of Arrests |

Defibrillation not Attempted |

Early defibrillation(<3 min) |

Late defibrillation(>3min) |

|||

|

102 |

24(23.5%) |

45(44.1%) |

33(32.3%) |

|||

|

Revived |

Not Revived |

Revived |

Not Revived |

Revived |

Not Revived |

|

|

2 |

22 |

45(100%) |

0 |

7(21.2%) |

26(78.8%) |

|

Table 3 Distribution of patients where defibrillation was attempted and their outcome

The cardiac rhythm most frequently observed was asystole (40 cases, 39.2%), followed by ventricular fibrillation (VF) (36 cases, 35.3%) and pulse less ventricular tachycardia (VT) (18 cases, 17.6%). The least observed rhythm was pulse less electrical activity (PEA) (8 cases, 7.84%). Among all these rhythms, the revival rate was highest in patients with VF (26 cases, 72.2%). It was followed by pulse less VT (11 cases, 61.1%) and then asystole (18 cases, 45%). None of the patients with PEA could be revived. All the patients with PEA were diagnosed to have sepsis.

In 12 cases, the response time of doctors was not recorded. Out of the remaining 90 forms analyzed, the mean response time was 2.1±0.6minutes. There were 27 cases with a response time of over 5minutes. Of these, 20 were between midnight and 6 am. 7 of those cases were in private/new private wards and rest from different wards of the hospital. In all the patients of OT, RR, ICU and HDU, the average response time was 1.2±0.4 minutes. A total of 33 patients were resuscitated between midnight and 6 am, and of these, 8 were resuscitated successfully. The initial neurological assessment showed a GCS score of 8 or less in all patients who died subsequently; whereas all the patients who were discharged, had initial GCS score of 13 or more.

A total of 54(52.9%) patients were revived and among them, 7 (12.9% of all revived and 6.9% of total arrest victims) patients were discharged from the hospital. This result is similar to those obtained in other series where the success rate has ranged from 2.1-2 %.3–7 There have been a lot of studies on the survival of cardiac arrest patients in different wards of the hospital and whether revival rate is more in witnessed arrests. Some papers quote the incidence of low survival rates in cardiac arrests on general wards.3 others, however, quote low survival rates in the ICU.8 In our study we found a low revival rate (38.46%) in ICU patients compared to patients in other areas of the hospital; the reason in most probability being already continuing inotropic as well as respiratory support and a poorer prognosis due to the critical nature of their illnesses. All the revived arrest victims were witnessed by either doctors or some paramedical worker in our study. There is a higher probability of a witnessed arrest being successfully resuscitated because of early intervention (i.e. initiation of CPR and defibrillation) by the emergency team.2

Survival varies greatly by initial cardiac rhythm, with higher success rates for resuscitation from ventricular arrhythmias and markedly worse outcomes if asystole or PEA was initially noted.10 In our study, 66.7% of VF patients could be revived initially, followed by 40% and 11.4% of patients with pulse less VT and asystole, respectively.2 Duration of CPR also had a negative correlation with survivability in our study which is comparable to other studies.3 our response time of 87.1% within 5minutes. It has been variously reported by various authors.2,4,6,7,11 We should point out that our figure does not include cases where the arrest was witnessed by an anesthesiologist. It was, however, noted that a significant number of doctors from non-anaesthesia specialties, had difficulties in performing CPR most of the time. In critical care areas, the response time is expectedly faster compared to wards. This is due to the constant presence of doctors and other paramedical staff in these areas. In case of arrest calls from new private wards, it takes a minimum of 3minutes for an anaesthesia resident to reach the site after the call is received; the average time being 5.1minutes.

It is to be noted that, the new private ward is located in a separate building in our hospital and thus, attending a call from there depends upon a lot of other factors. On the other hand, calls from private ward take a minimum of 2 minutes for a resident to attend, with an average time of 2.9minutes. This justifies the presence of a qualified resuscitation team in every ward and floor of the hospital, so that victims of cardiac arrest could be attended in haste.10 Every ward in our hospital has all the drugs and equipments for management of cardiac arrests, but, it was noted that, the arrangement of things in the trolley was not appropriate in some of the wards, which led to undue delay during the procedure. Therefore, the presence of a systematic cardiac arrest trolley in each and every ward of the hospital, and the knowledge of the same, is also essential. Mortality among patients who are revived following a CPR is high.12 This figure varies from 54% to 83%.3–10 Similarly, a large proportion dies within 24hours of the arrest.13 Our study shows an incidence of 87.1% (47 deaths out of 54 revived patients) of total deaths among those who survived and an incidence of 68.5% of deaths within 24hr.

In our institution, conventional defibrillators are located in all areas of the hospital. In critical care areas, at least one resident doctor trained in the use of the defibrillator is always present. Defibrillation can be performed promptly in these locations when indicated. In non-critical units, use of defibrillators is not prompt, as nurses are not allowed to defibrillate cardiac arrest patients. So in general wards, defibrillation is often delayed till the arrival of the resuscitation team, which obviously is a deterrent to a successful outcome of CPR. Automated external defibrillators are not in use in our hospital at present. By training appropriate paramedical staff including nurses to use conventional and automated external defibrillators and giving them the authority to use them, it may be possible to reduce the time from cardiac arrest to defibrillation. The rapid defibrillation, especially for in-patients, in which the goal is delivery of a shock within 3minutes of victim collapse leads to favourable outcome.2,8,9,10,14 Initial neurological status reflects the severity of global ischemia sustained during the circulatory arrest, and it is an accepted predictor of post-CPR recovery. The GCS is an established measure of initial neurological status and in the present study; it correlated with survival to hospital discharge. Some investigators have estimated that cerebral blood flow is 3-1% of normal when CPR is begun immediately but decreases progressively as CPR continues and intracranial pressures rise. Nevertheless, acceptable neurological recovery has been reported even after prolonged CPR.9

The principal shortcomings that we faced in our hospital were inexperience and improper knowledge of proper resuscitation protocol amongst residents of other medical specialties other than anaesthesia and critical care, delay in reaching certain wards of the hospital and lack of awareness among some paramedical personnel. Introduction of a Medical Emergency Team system for adult in-hospital patients should be considered, with special attention to details of implementation (eg, composition and availability of the team, calling criteria, education and awareness of hospital staff, etc.).15 Training of residents of various specialities as well as paramedical staff is a basic necessity while introducing such an approach for management of cardiac arrest victims.16,17 Our observation may be limited by the fact that it was conducted in tertiary care centre with adequate training and resuscitation facilities.18 Also, the data were in-hospital data for patients who were admitted in the hospital. This may not be applicable out of hospital cardiac arrest or less trained staff or lesser equipped hospital facilities.19

In conclusion, survival from cardiac arrest depends on a series of critical interventions. There are additional variables which modify the outcome, the most important being the interval between ‘arrest to initiation of CPR’ and ‘arrest to defibrillation’. Patients who developed ventricular fibrillation or tachycardia were more likely to survive than patients who developed asystole.

None.

Authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2014 Dutta, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.