Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6437

Case Report Volume 12 Issue 5

Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Oman

Correspondence: Dr. Nigel Kuriakose, Specialist Anesthesiologist, Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Department of Anesthesia and ICU, PO Box 38, PC 123 Sultanate of Oman, Tel 00968-95804800

Received: November 06, 2020 | Published: November 11, 2020

Citation: Nigel DR, Ali DR, Shabadi DR, et al. Bracing a prudent anesthetic challenge: a super-morbidly obese patient posted for an emergency laparotomy: a case report. J Anesth Crit Care Open Access. 2020;12(5):181-183. DOI: 10.15406/jaccoa.2020.12.00457

A 36-year-old lady weighing 200kgs (BMI 71) was brought to the hospital complaining of abdominal pain, distention and vomiting for one day. She was a working office staff until 2 days prior to hospital admission.She gave history of hirsutism, an untreated umbilical hernia and was diabetic on oral hypoglycemics. She didn’t have any hospital admission in the recent past.She developed respiratory distress soon after admission. Her saturation improved to 94-96% after giving her oxygen via non-rebreather mask. Decompression via nasogastric tube drained 1.9 liters and her symptoms temporarily improved with it. Her ECG showed sinus tachycardia and her inflammatory markers were raised. She was oliguric. Her initial blood pressure was 147/81 mm Hg.

Preoperative bedside transthoracic echocardiography showed a limited study in the emergency room due to her truncal obesity. Her inferior venacava could not be visualized. As the patient desaturated with worsening metabolic acidosis(venous blood gas: pH 7.27, bicarbonate 17, lactate 7.2, random blood sugar 18.2), she was started on non-invasive ventilation.

On examination her abdomen showed a gangrenous ventral hernia (about 30x25cms) around the umbilicus. There was a necrotic ulcer (about 4x2cm) on the abdominal wall. Her abdominal girth did not facilitate radiological CT imaging and her weight was above what the gantry could permit. Even the attempted exposure for lateral x-ray abdomen was inadequate. The arterial blood gas showed acidosis (pH 7.26) with impending shock and she was started on noradrenaline infusion (rate 0.8-1micg/kg/min). The surgeons decided to post her for an exploratory laparotomy to rule out obstructed hernia, intestinal obstruction and bowel gangrene.

Patient was assessed with a Mallampati score IV, mouth opening 1 finger breadth, neck circumference 33cms with no loose teeth. High risk informed consent was taken from the patient and her brother for emergency laparotomy under general anaesthesia. Awake fiberoptic intubation and post-operative elective ventilation in the intensive care unit was planned. The patient was shifted to the operating room propped up on NIV facemask. Her baseline vitals on arrival to the operating room were heart rate 112 bpm, blood pressure 70/40 mmHg and saturation 87%.

Difficult airway protocol was initiated and the airway trolley comprising two extra-long laryngoscope blades with short handles, C-MAC, a cricothyrotomy set, laryngeal mask airways and fiber optic bronchoscope were kept available for anticipated difficult airway instrumentation and access. She was shifted onto the specially designed table for obese patients (TRUMPF MARS, Medizin Systeme, 450kg limit, Saalfeld, Germany) (Figure 1). The patient had difficult intravenous access and a 22 G intravenous canula was secured with ultrasound guidance on the dorsum of the left hand. Standard monitors were attached.

Figure 1 The super-morbidly obese patient with a gangrenous ventral hernia posted for the emergency laparotomy. She was placed on the TRUMPF MARS operating table (Medizin Systeme, 450kg limit, Saalfeld, Germany) in the ramp position.

Under ultrasound guidance right radial arterial cannulation was performed for invasive blood pressure monitoring. After testing the patency of the nostrils, awake fiberoptic intubation through the left nostril was planned with a cuffed 7mm internal diameter flexometallic endotracheal tube. She was explained about awake fiberoptic intubation, for which she agreed and was kept in ramp position. Intravenous granisetron 1mg was given as an antiemetic. The NIV mask was removed just before airway manipulation and she was kept on high flow oxygen via face mask. The patient was intubated via the nasal route in the first attempt on visualization of the vocal cords by instilling 2 mls of 4 % lignocaine.The endotracheal tube was positioned above the carina and fixed after visual and waveform capnography confirmation. Maintenance was with oxygen and air with minimal titrated desflurane. The anesthetic plane was deepened with intravenous ketamine 50 mg, titrated doses of propofol 60 mg and cisatracurium 10 mg. Under all aseptic precautions the right internal jugular vein was cannulated under ultrasound guidance. Patient was positioned well with gel pads and stirrups. Her intra-operative findings were para-umbilical hernia with ischemia and edematous bowel segments. About 3500ml of seropurulent fluid with flakes in the sac were seen. The lesser curvature of the stomach had a large perforation of 4x3cm diameter with intestinal contents and mucous filled the supra-colic compartment. Intraoperatively the patient was hypotensive and oliguric. Potassium was 6 on ABG with continuing acidosis. Fluid challenges were given totaling to about 5.5 liters of normal saline. Despite starting noradrenaline infusion, the patient was not maintaining blood pressures even after the third fluid challenge.

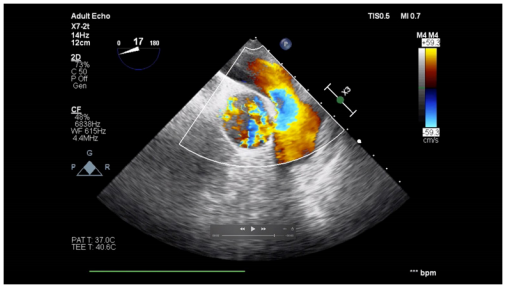

TEE (Trans- Esophageal Echocardiogram) was performed to determine the cardiac status of the patient and to decipher the cause of sepsis. TEE showed poor left ventricular function with ejection fraction approximately 30- 35%. The left ventricular filling was not indicating severe hypovolemia. The septal wall and inferior septal wall were dyskinetic. The right ventricle was dilated (Grade II). There was a hypokinetic free wall and dyskinetic right ventricular outflow tract (Figure 2). Based on the TEE findings it was decided to start intravenous dobutamine infusion and diuretics along with Noradrenaline infusion. At the end of surgery, under vision using C-MAC (KARL STORZ video laryngoscopes, Tuttlingen, Germany) and using a bougie, the endotracheal tube was exchanged with a cuffed oral endotracheal tube of 7 mm internal diameter.The vitals at the time of shifting were heart rate 140 beats/min, arterial blood pressure 80/40 mmHg, saturation 97%. Urine output was 25mls. ABG showed metabolic acidosis and hyperkalemia for which correction was started.

Figure 2 Upper esophageal aortic short axis view of Transesophageal Echocardiography with color flow doppler showing the flow across the main pulmonary artery trunk, right and left pulmonary arteries.

Patient was shifted to ICU for post-operative ventilation. She continued to be very unstable requiring inotropic support with dobutamine, and noradrenaline infusion and her saturation was also low. Her renal functions parameters continued to deteriorate and acidemia worsened. She developed multi organ failure and unfortunately succumbed to her illness 24 hours later despite our best resuscitative measures.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2016, more than 1.9 billion adults were overweight, and of these, over 650 million were obese.1 Obesity is associated with an increased incidence of medical co-morbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnea, cardiopulmonary disease, venous thromboembolism, and psychosocial disease. The perioperative management of a super morbidly obese patient may encounter several challenges. Our patient was drowsy, orthopneic and breathless to move on her own but she was able to comprehend our commands. She was shifted from the emergency room in a propped-up trolley on non-invasive ventilation support. Then she was shifted on to the specialized operating table for obese patients. We positioned her with adequate gel pads and stirrups to cause least pressure point compressions and better patient comfort. Improper padding may cause neurological injuries, compression injuries, renal failure and potentially fatal complications.2 In a study by Bostanjian et al.,3 they described six patients undergoing bariatric surgery where gluteal muscle rhabdomyolysis, compartment syndrome and subsequent renal failure occurred due to the pressure from the operating table with fatal outcomes in three of the cases. The anticipated difficulties in intubation and hemodynamic fluctuations following induction, prompted us to proceed for an awake fiberoptic intubation. The compromised functional residual capacity, expiratory reserve volume, and total lung capacity would result in a ventilation perfusion mismatch and significant increase in oxygen consumption, cardiac output, and pulmonary artery pressures. The reverse trendelenberg position (30 degrees) was expected to provide maximum safe apnea period to our patient.4 The terms “Safe Apnoea Period” (SAP),4,5 or “Duration of Apnea Without Desaturation” (DAWD) are both used to describe the length of time before potentially harmful levels of hypoxemia set in.6 In the event of airway difficulties, the risk of serious complications in morbidly obese patients is reported to be four times higher than that of lean patients.7 In a retrospective review of major complications of airway management in the UK (NAP4), 25% of 77 obese patients, in whom airway management complications were reported, brain damage or death were reported.8 Karkouti et al. showed mouth opening, chin protrusion and atlanto-occipital extension as useful predictors in difficult laryngoscopic tracheal intubation.9 Gonzalez et al meanwhile used intubation difficulty scale (IDS) to find an association between difficult intubation and increased neck circumference (40–42 cm) or Mallampati score>=3.10 There was an increased probability of the presence of both increased neck diameter and increased Mallampati class in morbidly obese patients. The experience of the anesthesiologist is also an important determinant for securing the airway in morbidly obese patients.11 In super obese patients posted for emergency surgeries the probable causes of shock should be ruled out. In this patient, an incarcerated umbilical hernia, intestinal obstruction, or perforation was suspected. A major concern for us was an uninvestigated preoperative cardiac functional status because of her moribund obesity. The attempt for transthoracic echocardiography failed due to difficulties in positioning and the window was obscured due to her truncal obesity. The usual causes of shock are occult hemorrhage (such as upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage without hematemesis or melena or concealed obstetric/ gynecological blood loss), hidden sepsis (silent intraperitoneal perforation, early meningococcemia, or toxic shock syndrome), or a silent cardiovascular event (pulmonary embolus, myocardial infarction). In shock states unresponsive to intravascular fluid expansion, or in cardiogenic shock where fluid challenges may be hazardous, inotropic therapy is required. The choice of inotrope should be guided by the nature of the problem and the hemodynamic parameters in individual cases.Noradrenaline has been shown to increase cardiac output, renal blood flow, and urine output when used in septic shock.12 As with all inotropes, noradrenaline infusions must be started cautiously and titrated to achieve an adequate mean arterial blood pressure, typically 65 mm Hg. Inotropes should be given via a dedicated lumen through a central venous line. In obesity the noninvasive blood pressure monitoring can be misleading because of the disparity of cuff. When critical therapeutic decisions are required, invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring is preferred. Central venous cannulation on obese patients can be technically difficult. Ottestad et al reported a risky complication while inserting a subclavian central venous line in an obese patient.13 In all other shock states, except in cardiogenic shock with left ventricular failure, intravenous fluids are indicated. This should be guided by invasive hemodynamic monitoring and repeated intravenous fluid challenges with central venous pressure guidance. Schulmeyer MC et al showed in their study on 98 patients that intraoperative TEE was effective in unveiling relevant clinical findings and useful information in high-risk patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. The use of intraoperative TEE enabled timely changes in drug therapy and fluid administration which brought about positive outcomes in these patients. Postoperative management changes were mostly made because of new diagnosis (14%) and new left ventricular wall motion abnormalities (9%).14,15

In managing an unoptimized morbidly obese patient for emergency surgery; proper positioning, decision making in securing the airway and proper invasive monitoring are important in ensuring patient safety. The intraoperative management with intravenous fluids and inotropes can be judiciously managed with the help of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) thereby ensuring a safer intraoperative and post-operative period.

©2020 Nigel, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.