eISSN: 2574-9838

Mini Review Volume 3 Issue 1

Italian Hospital of Buenos Aires, Argentina

Correspondence: Francisco Nally, Italian Hospital of Buenos Aires, Argentina

Received: October 02, 2017 | Published: January 12, 2018

Citation: Nally F, Zanotti G, Comba F, et al. Psoas abscess associated to hip septic arthritis 2 stages treatment for 2 cases. Int Phys Med Rehab J. 2018;3(1):13-16. DOI: 10.15406/ipmrj.2018.03.00067

Introduction: Psoas abscess is a collection of pus within the psoas muscle compartment that can access the hip joint in rare opportunities through the psoas bursa. Usual treatment involves articular toillet at early diagnosis, but when not suspected, secondary arthritis or septic arthroplasty loosening may occur. To our knowledge there are no reports of 2 stages radical treatment for this case.

Material and methods: We describe two cases of primary psoas abscess with partial response to oral antibiotic treatment in whom the infection spread to the hip joint, leading to a septic arthritis. The first case was a 60 year old diabetic male patient with 2 months thigh pain and fever treated with oral antibiotics and torpid evolution. CT scan and MRI showed a left psoas abscess in contact with the hip joint interpreted as an advanced hip arthritis with severe cartilage damage. The second case is a 42 year old male patient who had a psoas muscle tear while playing football 3 weeks before consultation that complicated with psoas infection and bad response to antibiotics. MRI showed a clear collection in iliac fossa and advanced articular damage associated to synovitis. 2 stage treatments consisted in an initial surgery through a posterior approach, debridement of inflammatory tissues, neck osteotomy and acetabular reaming adding a temporary antibiotic impregnated cement spacer for the resected femoral head. 6 weeks after when intravenous antibiotic treatment was completed and laboratory inflammatory parameters were controlled; a second stage surgery was planified: Conversion to an hybrid arthroplasty for the first case and a non cemented total hip arthroplasty for the second case.

Results: Differed anatomy showed chronic inflammation compatible with osteomielitis for both cases, no germs were isolated in the cultures for the case 1 and a staphylococcus aureus meticilin resistant organism for the second case. At conversion stage cement spacer loaded with antibiotics did not mantain articular length witch made conversion more demanding, suggesting that a preformed spacer can cope with both objectives, controlling infection and maintaining articular length. 2 year follow up with excellent clinical results, infection markers controlled, no complications reported. Harris Hip Score were over 90 in both cases.

Conclusion: Though it is a rare complication of psoas abscess, septic hip arthritis is an invalidating disease. Radical treatment with 2 stages surgery, accomplished good results for this devastating arthropathy. An Articulated spacer is suggested.

Psoas abscess is a collection of pus within the psoas muscle compartment that can access the hip joint in rare opportunities through the psoas bursa. Usual treatment involves articular debridement at early diagnosis and psoas drainage in an open fashion or by to mographic guided percutaneous drainage, but when not suspected, secondary arthritis and high incidence of septic arthroplasty loosening may occur. To our knowledge there are no reports of 2 stages radical treatment for these cases.

We describe two cases of primary psoas abscess with partial response to oral antibiotic treatment in whom the infection spread to the hip joint, leading to a septic arthritis. The first case was a 60 year old diabetic male patient with 2 months thigh pain and fever treated with oral antibiotics and torpid evolution. CT scan and MRI showed a left psoas abscess in contact with the hip joint interpreted as chronified hip arthritis with severe cartilage damage. On examination he was mildy pyrexial and haemodynamically stable. His ability to weight bear was impeded by groin pain and he lay in a supine position with the right hip flexed for comfort. There was painful restriction in hip range of motion with discomfort in external/internal rotation and full extension beyond 30 degrees of flexion. There was localized tenderness over the right hip capsule. Abdominal, spinal and other locomotor examination was normal.

The second case is a 42 year old male patient who had a psoas muscle tear while playing football 3 weeks before consultation that complicated with psoas infection and bad response to antibiotics. MRI showed a clear collection in iliac fossa and advanced articular damage associated to synovitis.

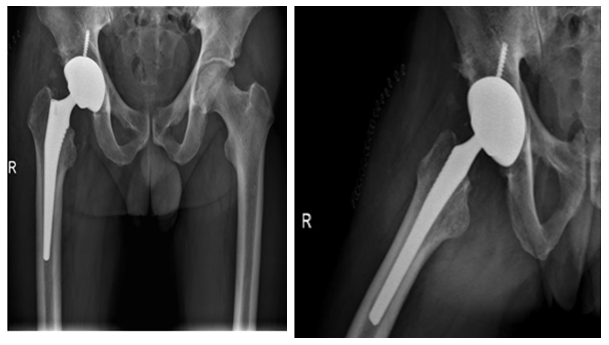

Two stage treatments consisted in an initial surgery through a posterior approach, debridement of inflammatory tissues, neck osteotomy and acetabular reaming adding a temporal non-articulated antibiotic impregnated cement spacer for the resected femoral head. 6 weeks after surgery when intravenous antibiotic treatment was completed and laboratory inflammatory parameters were controlled, a second stage surgery was planified: Conversion to a hybrid arthroplasty for the first case and a non cemented total hip arthroplasty for the second case (Figure 1) (Figure 2).

The psoas abscess was first described in 1881, and referred to as psoitis.1 Its estimated worldwide incidence was 3.9 cases per year in 19852 and 12 cases per year in 1992, a rise believed to be attributed more to improvements in radiological imaging rather than a true increase in the incidence of the condition.3 The Psoas muscle arises from the transverse processes and lateral aspects of the vertebral bodies between T12 and L5 traveling downwards across the pelvic brim to insert on the lesser trochanter. A bursa is present between the psoas muscle tendon insertion at the lesser trochanter and the hip capsule. This bursa is a potential route by which an infection from a psoas abscess can gain access to the hip joint. Infection can also track to the hip capsule directly along the iliopsoas muscle between the iliofemoral and iliopubic ligaments.4 The psoas has a rich blood supply that is believed to predispose it to haematogenous spread from sites of occult infection.5 Secondary psoas abscesses occur when there is a direct extension from an adjacent retroperitoneal or intra-abdominal infection. The most common cause of secondary abscesses in the literature is spread from the gastro-intestinal tract, such as in Crohn’s disease, appendicitis, diverticulitis and colon cancer. Other causes of secondary abscesses include vertebral osteomyelitis and urinary tract infections.6

In recent years, there has been an increase in immune compromised patients (HIV), intravenous drug users and patients with chronic illnesses such as diabetes or renal failure.7,8 The symptoms of a psoas abscess can be insidious and non-specific. Patients often present with fever, weight loss, limp, flank or abdominal pain. The key to the diagnosis lies in the physical examination. The patient is classically more comfortable lying supine with the leg slightly flexed and externally rotated. The pain is often exacerbated by flexing the hip against resistance.

Laboratory tests may reveal a raised white cell count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Radiological images should be used to make the diagnosis. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is the image of choice and is diagnostic in 80-100% of cases9–11 compared to 60% with ultrasonography.5 The CT scan also helps to identify the aetiology and can guide the percutaneous drainage/aspiration of the abscess. A scan of a psoas abscess would reveal an enlarged psoas muscle belly compared to the unaffected other side. They may also show focal areas of low density and/or gas within the affected region.12 The bacteriology is different in a primary and secondary abscess. Staphylococcus aureus is the pathogen in 88% of primary psoas abscesses6 other pathogens include streptococci, Escherichia coli7Pseudomonas aeruginosa7 and Proteus mirabilis.13 Cultures are often mixed in secondary abscesses, with E. coli and bacteriodes spp occurring most commonly. Other pathogens include Staphylococcus and Streptococcus spp.6 Mycobacterium tuberculosis is also a frequent causative organism in areas where it is endemic, however is rare in the developed world.

The management is through antibiotic treatment accompanied by abscess drainage. Broad spectrum antibiotics should initially be commenced until microbiology cultures of the abscess fluid hone in on the specific antimicrobial sensitivities. Initial coverage should include staphylococcal and enteric organisms for which agents such as clindamycin, antistaphylococcal penicillin, and an aminoglycoside may be used.11 Drainage of the abscess can be performed surgically or percutaneously. CT-guided percutaneous drainage is the method of choice.10 and should be utilized where possible. However surgical drainage may be advantageous if the abscess is secondary to gastro-intestinal disease, as it also provides an opportunity to resect the diseased bowel.10 The prognosis is generally good. Primary psoas abscess has a better prognosis than secondary. Mortality from an undrained abscess is close to 100%, with septicaemia being the most common cause of death.2

Ideal treatment should be to preserve the joint but this is not always possible, systematic approach for this high suspicion entity would be rapid MRI images to acknowledge the cartilage damage and subsequent osteomielitis, and two stage surgery to control infection and return to normal life as soon as possible.14-16

Though it is a rare complication of psoas abscess, septic hip arthritis is an invalidating desease. Radical treatment with 2 stages surgery, accomplished good results for this devastating artropathy. At conversion stage cement spacer loaded with antibiotics did not mantain articular length witch made conversion more demanding, suggesting that a preformed spacer can cope with both objectives, controlling infection and maintaining articular length.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2018 Nally, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.