eISSN: 2574-9838

Mini Review Volume 1 Issue 2

Department of Health Policy and Management, Rollins school of Public Health of Emory University, USA

Correspondence: VL Phillips, Department of Health Policy and Management, Rollins School of Public Health Of Emory University, USA

Received: April 04, 2017 | Published: May 4, 2017

Citation: Phillips VL. Home health care reimbursement and the supply of therapy services. Int Phys Med Rehab J. 2017;1(2):23-25. DOI: 10.15406/ipmrj.2017.01.00006

Physical and other skilled therapies are critical services which promote functional recovery, increase quality of life and prevent deterioration of people with disabling injuries or complications from chronic conditions, ranging from falls to stroke to spinal cord injuries. In the United States Medicare is the primary insurer for those age 65 and older and the long-term disabled, both prime candidates for physical therapy. Reimbursement levels and rules related to payment greatly affect the supply of therapy services and, in turn, who and how many people in need receive them. This paper reviews Medicare payment policies for home health care services and traces their impact on service supply.

Physical therapy, in particular, is recognized as a critical input into to ensure patient recovery from a disabling event. It can also help maintain function and serve as an effective pain management tool. Physical therapists generally work one-on-one with patients and develop a personalized treatment plan which can include: therapeutic exercise, work with assistive devices, and electrotherapeutic modalities. Evidence shows that physical therapy can help prevent falls, a significant cause of morbidity, mortality and hospitalizations in the elderly.1

Acknowledging its value, along with other skilled services, Congress included home health benefits as part of the original legislation creating Medicare. The statute requires patients to have a predictable, recurring need for skilled services and the benefit once they return to the community. Increasingly, beneficiaries need on-going skilled services through HHC to maintain their health status. Nearly two-thirds of Medicare beneficiaries have two or more chronic conditions and approximately one in five has five or more chronic conditions,2 Currently, 9% of all Medicare beneficiaries use HHC at a cost to Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the agency responsible for program oversight, of $18 billion annually.3

Medicare covers skilled nursing services; physical, speech and occupational therapy; medical social work services, and aide assistance for homebound beneficiaries through its Part A and Part B home health care (HHC) benefits. To become eligible for HHC, a beneficiary must be homebound and require skilled services part-time, less than eight hours per day, or intermittently, less than seven days per week. In addition, a physician must certify need and determine a plan of care to meet defined goals for a 60-day service episode.4 Beneficiaries are eligible for HHC following a hospitalization or a stay in a skilled nursing facility or through community referral. In 2015, two-thirds of total HHC episodes were provided to beneficiaries from the community.5

Being eligible, however, has not guaranteed that Medicare will pay for prescribed services. The ultimate determination is made by the local fiscal intermediary under guidance from the Secretary for Health and Human Services. A tension has existed in the program regarding its purpose and goals and the need to control costs, particularly given the growth of demand and suppl.6

Provider reimbursement systems and levels of payment over time reflect the need to control costs. Medicare has relied on three payment systems by which to reimburse providers:

1) fee-for-service with an annual limit;Figure 1 diagrams HHC expenditures and the CMS reimbursement systems over time.

Fee-for-service reimbursementInitially, Medicare reimbursed home health agencies through fee-for-service or the agency charge per visit based on their costs. HHC expenditures remained relatively low with little growth as the benefit had annual limits on the benefit and required a prior hospitalization before service would be authorized. The first significant increase in spending began with passage of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) in 1980. It removed both the need for a prior hospital stay and annual limits in the belief that increasing HHC use would reduce hospital and skilled nursing facility (SNF) costs for Medicare, along with long term care costs for Medicaid.

OBRA was followed in 1983 by implementation of the hospital prospective payment system (PPS). Under this system CMS paid hospitals based on patient diagnosis not per day or by length of stay declined. Subsequently more and sicker patients were referred to HHC. From 1980 to 1985, Medicare HHC expenditure increased by 168%. CMS tightened per-visit reimbursement in 1983, attempting to curb the growth.7

A series of lawsuits led to the exponential growth of spending in the late 80s as many beneficiaries contended that CMS was denying them services for which they qualified in an effort to control costs. For example, in 1984, the New York state court ruled in favor of the beneficiary in Kuebler v. Secretary U. S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) in a suit alleging use of an inappropriate standards in evaluating HHC need and of ignoring the physician’s recommendation regarding extending care.8 Duggan V Bowen8 in 1988 had the most far-reaching influence for HHC .9 The ruling expanded coverage by redefining loosening the criteria to qualify for services, for example, the definition of homebound became less restrictive.

After the 1988 ruling, HHC use exploded. Over the next seven years, the number of beneficiaries receiving skilled services rose 225%; annual visits per HHC user increased 343% and HHC spending rose an average of 33% per year.10 CMS tackled HHC expenditure growth in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA). It moved the industry from cost-based reimbursement to its own prospective payment system, similar to that for hospitals.

Prospective payment reimbursementIn 1997, an Interim Payment System (IPS) reduced per-visit reimbursement and introduced a first-time annual per-beneficiary spending cap.11 Full PPS was implemented in 2000 and linked payments to beneficiary assignment to one of 80 home health resource groups (HHRGs), reflecting clinical, functional and service utilization factors and paid for a 60-day renewable episode of care based on the HHRG.12 Between 2001 and 2010, the percentage of beneficiaries using HHC increased at a much lower rate, 3.9% annually or one-tenth of the rate in the earlier period, but spending continued to climb.13

Given their sustained growth, the Affordable Care Act targeted HHC expenditures from several angle.14 It instituted a five percent reduction in provider reimbursement in 2011, and phased in a further 17% reduction by 2017.15 Along with the payment reductions, the law set a permanent cap on high–user outlier payments, mandated reviews before select visits and ramped up the HHC antifraud campaign. The actions have successfully bent the cost curve downward with recent signs it has hit a plateau at a much lower spending level.

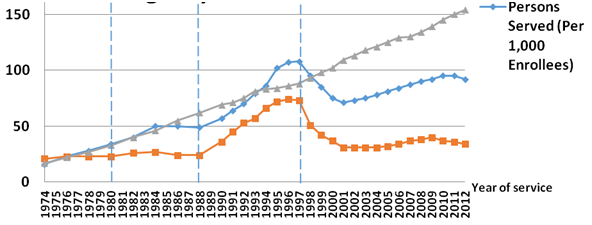

Supply of services under different reimbursement schemesWhile over time CMS has been working to control expenditures with different payment systems, agencies have been working to increase revenues. Figure 2 shows how rapidly agencies have responded to reimbursement changes in terms of client numbers, visits per client and per visit charges. When the hospital stay requirement to qualify for service was eliminated in 1980, the number of persons served rose dramatically as did visit charges. This propelled sustained growth in expenditure and prompted introduction of the spending cap person introduced in 1983.

While visits and number of enrollees served trended downward for a short time, charges continued to rise thereby increasing agency revenues. In response agencies, however, claimed the smaller client pool was sicker and increased visit charges.

In 1988 when program eligibility criteria were loosened, all three rose dramatically. Following the Duggan ruling, under cost-based reimbursement, the number of Medicare certified agencies increased nearly 70% from approximately 6,000 in 1990 to more than 10,000 in 1996.16 Both persons served and visits rose dramatically. Visit charges remained on trend, but over this period home health aide visits began to constitute an increasing proportion of overall visits. The share of visits provided by aides rose from one third to almost half, improving agency margins by using more lower cost staff, by the end of the 1980s.17

Introduction of the prospective payment radically affected the industry with the number of home health agencies falling by two-thirds. Many of the remaining agencies reacted strategically to the prospective payment system and increased the number of therapy visits provided as they were reimbursed at a higher rate. Visits per person also declined which helped maintain revenues overall. Up from 10% in 1997, therapy visits constituted 17% of all visits by 2000. Once the industry stabilized, pre-PPS rates of growth returned for persons served and charges.

Provisions of the ACA have begun to reduce visits per person and number of enrollees. The trends in increasing episode charges is a function of the continued shift in serving more acute patients where reimbursement is higher and profit margins are likely larger. Therapy visits now constitute 35% of all visits whereas aide visits have fallen to 12%.

While expenditures concerns will remain a key concern, HHC services will grow in importance as the population overall ages and people live longer, often with multiple chronic conditions. The provision of home health services promotes functional recovery, increases quality of life and prevents functional deterioration which may contribute to nursing home placement.

CMS should work to ensure that provider reimbursement is sufficient to ensure provider willingness to cover needed services and that reimbursement levels encourage appropriate provision of services across the service spectrum from skilled nursing to physical therapy to home health aide. In addition, CMS should also evaluate the continuum of care constituted by Medicare services and consider how HHC can be used most effectively to substitute for other services or to complement them to offset expansion costs in other areas. Both dimensions are areas ripe for future research.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Phillips. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.