International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9889

Case Report Volume 7 Issue 6

1Associate Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, India

2Associate Professor, Department of Urology, India

3Professor, Department of Pathology, India

Correspondence:

Received: October 11, 2021 | Published: November 16, 2021

Citation: Singla R, Arora A, Bora G, et al. Spontaneous isolated intraperitoneal rupture of urinary bladder after normal vaginal delivery presenting as puerperal sepsis. Int J Pregn and Chi Birth. 2021;7(6):141-143. DOI: 10.15406/ipcb.2021.07.00245

Spontaneous isolated intraperitoneal rupture of urinary bladder is a rare urological complication of normal delivery. This complication is usually related to prolonged labour, failure to empty bladder in second stage of labour, use of forceps/ ventouse, postpartum urinary retention, vaginal birth after caesarean section and usually presents immediately after delivery. We report the case of a patient with spontaneous isolated intraperitoneal rupture of urinary bladder after normal vaginal delivery in the absence of any risk factor. She presented on day 5 postpartum with features suggestive of puerperal sepsis with pyoperitoneum with acute kidney injury. Absence of unhealthy lochia and later, normal-looking uterus and adnexa during laparotomy led to the suspicion of alternate cause for seropurulent ascites. Further exploration revealed rent in the urinary bladder with necrosed margins. High index of suspicion of alternate diagnosis should be maintained if some of the clinical findings are not supportive of provisional initial diagnosis.

Keywords: urinary bladder, intraperitoneal, spontaneous bladder rupture, vaginal delivery postpartum

Spontaneous isolated intraperitoneal rupture of urinary bladder is an unexpected urological complication of a normal delivery. In most of the previous case reports, one or the other risk factors have been defined such as prolonged labour, failure to empty the bladder in second stage of labour,1,2 use of forceps or ventouse,3,4 postpartum urinary retention,5 vaginal birth after caesarean section6 or obstructed labour (generally with uterine rupture or vaginal laceration),7,8 history of radiation therapy, indwelling catheters and neurogenic bladder. When rupture of bladder occurs, usually it occurs during the process of delivery and hence, manifests immediately. In the absence of immediate presentation and any risk factors, it is not suspected and hence, likely to be overlooked.

We report a case of woman with spontaneous isolated intraperitoneal rupture of urinary bladder following normal delivery. Her presentation was similar to puerperal sepsis with pyoperitoneum with acute kidney injury (AKI) and hence, initial management was empirically directed towards same. High index of suspicion based on subsequent clinical findings led to the diagnosis that could have been overlooked.

A 26-years old, P2012, day 5 postpartum following full term normal vaginal delivery presented to emergency room with complaints of abdominal distension and decreased urine output and decreased appetite for 2 days. Her antenatal period was uncomplicated. She had spontaneous onset of labour at 38weeks 3days. During labour, she did not receive epidural analgesia. After 6 hours of labour she had normal vaginal delivery. No instrumentation was required. A live born baby of 3.704kgs with Apgar scores of 8 and 9 was delivered. She was able to void normally during labor and after delivery of the baby. She was discharged from the hospital 2 days after delivery. She started having abdominal distension from day 3 which gradually increased till day 5 when she came to emergency. She was able to pass only small amount of urine from day 3 onwards. There was no history of high-grade fever, foul smelling discharge from vagina, excessive bleeding, nausea or vomiting.

In her Obstetric history, she had one full term normal vaginal delivery with uneventful postpartum period 5 years back and one ectopic pregnancy 3 years back for which she had undergone left side salpingectomy. She had no significant medical or surgical illness in past and belonged to middle socio-economic class.

On examination, she was afebrile, her pulse rate was 126/min, good volume, regular; Blood pressure was 130/90mmHg, respiratory rate was 20/min. Her abdomen was uniformly distended and tender. Fluid thrill was present. Per speculum examination revealed normal vagina and cervix, and healthy lochia. On per vaginum examination, os was closed, uterus was postpartum size. Urinary bladder was catheterised; only 20ml of urine was drained.

Her haemoglobin was 14gm%; TLC14200/cumm; Blood biochemistry revealed urea to be 120 mg/dl and creatinine 4mg%. Serum sodium was 135mEq/L and potassium was 5.1mEq/L. Ultrasonography revealed gross ascites, uterus of normal postpartum size with no retained products and normal-looking kidneys. Ascitic tap was performed which showed thin purulent fluid.

Even though the patient’s general condition was fair and vaginal examination was normal, large amount of purulent ascitic fluid provided compelling evidence in favour of diagnosis of puerperal sepsis with pyoperitoneum. AKI was also considered to be due to sepsis.

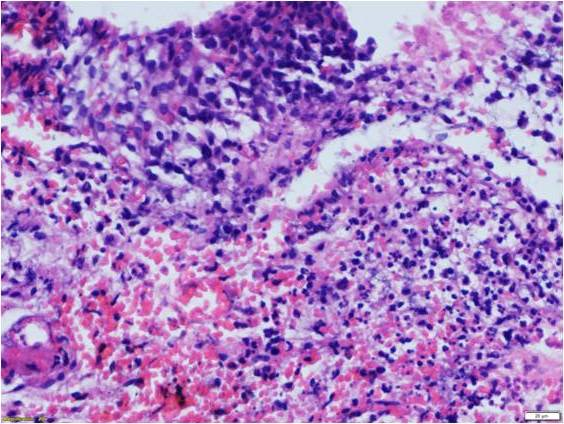

She received modified doses of Piperacillin- Tazobactum and Clindamycin that were continued in the post- operative period. Exploratory laparotomy was performed by midline vertical incision. Intra-operatively, 3 litres of purulent fluid was drained. Uterus, tubes and ovaries were normal. No other obvious intra-abdominal pathology could be detected. On further exploring, a small rent in the dome of urinary bladder measuring about 1×1cm, with necrotic margins, was found. Perforated part of bladder dome along with surrounding necrotic area was excised (Figure 1) and bladder was repaired using 2-0 vicryl in two layers and a 16 Fr suprapubic catheter was placed along with per-urethral 18 Fr Foley’s catheter. Integrity of the repaired bladder was checked intraoperatively by retrograde filling of the bladder with saline for any other perforation, which revealed none. Besides cellular counts and culture, the ascitic fluid sample was sent for creatinine levels that came out to be 11.9 mg/dl (i.e., 3 times that of serum creatinine). TLC was 2400/cumm, culture was sterile, AFB stain was negative. Histopathology revealed ulcerated to focally preserved transitional lining epithelium with dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate along with congested blood vessels in the subepithelium (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Photomicrograph of excised bladder tissue showing ulcerated lining epithelium and dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the subepithelium (H&E x200).

Post-operative course for the patient was uneventful, she remained afebrile. TLC and creatinine normalized. She was discharged form hospital in a stable condition on POD7, with both bladder catheters in situ that were removed 3 weeks later, once a cystogram revealed absence of any contrast extravasation. The patient voided well after the removal of the catheters.

Intraperitoneal rupture of bladder following normal delivery is rare; especially when patient is voiding regularly and no instrumentation or epidural analgesia are used. Due to large amount of purulent ascitic fluid and onset of symptoms from 3rd day, the initial diagnosis in present patient was pyoperitoneum due to puerperal sepsis with AKI. Hence, exploratory laparotomy was planned.

As she had a normal delivery, the infection was expected to be ascending from vagina. Absence of high fever and unhealthy lochia, and accumulation of huge amount of thin ascitic fluid over just 2 days after an uneventful delivery in a patient with no medical comorbidity raised suspicion of alternate pathology. Thorough inspection of bladder and bowel revealed a small perforation over the dome of urinary bladder. Cause of rupture was focal necrosis as revealed on histopathological examination. Decreased urine output in index patient was thought to be due to decreased oral intake and sepsis-related AKI. Blood urea and creatinine have been reported to be increased in earlier case reports too and may be attributed to urine absorption from the peritoneal cavity till equilibrium between concentration of urea and creatinine in ascitic fluid and plasma is reached.9

The bladder rupture in present patient was probably due to good size baby, though not macrosomic. The head of good size baby may have impinged upon and compressed bladder against pubic symphysis that may have led to vascular insult gradually progressing into necrosis (as confirmed by histopathology) and then rupture. In another case report bladder rupture was attributed to denervation injury leading to overdistension resulting in delayed presentation at 2 weeks postpartum.10

Our case highlights the importance of careful history and interpretation of examination findings that can clinch a rare but catastrophic diagnosis. Presentation may rarely be late11 as in our patient or diagnosis may be delayed.1 In such case, presenting symptoms are usually that of acute abdomen: pain, distension, oliguria or anuria, and fever.11 Urine may continue to drain spontaneously or by catheterization.1,12 Ascitic fluid analysis should include analysis for urea and creatinine if bladder injury is suspected.2,13 Rupture of bladder was not put into differential diagnosis in our patient because she had uncomplicated labour and delivery and no immediate urinary symptoms. In one of the case reports, initial diagnosis was severe urosepsis with renal failure until CT revealed bladder injury.3 Non-IV contrast CT in conjunction with retrograde cystogram is suggested for diagnosis.3,4 Computed tomography (CT) cystogram and cystoscopy in suspected cases can be confirmatory.1 Bigger rents can be diagnosed by ultrasonography that may reveal position of Foleys bulb in relation to uterus and ability to move catheter forward in to peritoneal cavity.

Further, it is needless to emphasize the importance of prompt intervention. Timely intervention is the key to reduction in morbidity and mortality related to any obstetric complication including this one. We would like to emphasize that the management of acute surgical abdomen should be based on clinical findings rather than being dependent upon radiological evidence. Decision for laparotomy, in such cases should not be delayed for the want of CT scan which may not be accessible everywhere. However, these imaging modalities must be utilized if they are readily available without compromising patient’s condition and when clinical suspicion is strong.

Index patient that seemed to be a straightforward case of puerperal sepsis, with no risk factors for bladder rupture turned out to be a case of urological catastrophe. A high index of suspicion is therefore required if clinical findings are not corroborating. During laparotomy, necrosed bladder tissue should be excised and repair should be done. The bladder drainage in the postoperative period should be ensured via dual drainage (urethral and suprapubic catheters) and integrity of the bladder should be checked. A check cystogram should be done after a period of 3-4 weeks before removal of the catheters.3

Trauma to urinary bladder due to necrosis during labor and delivery may not be evident immediately and may present later. One should not be biased towards the most-evident diagnosis and be ready to accept clinical findings that evolve subsequently but do not support initial diagnosis and use them as a guiding light towards correct diagnosis. Timely intervention is the key to reduction in morbidity related to any obstetric complication. Management of acute surgical abdomen should not be delayed for the want of evidence from higher imaging techniques which may not be accessible everywhere.

None.

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

None.

©2021 Singla, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.