International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9889

Case Report Volume 8 Issue 4

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2nd affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, China

Correspondence: Ying Xiao Yan, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2nd affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing city, Jiangsu Province, PR. China

Received: November 15, 2022 | Published: December 7, 2022

Citation: Chanda K, Lian LS, Abulikem G, et al. Second emergency transvaginal cerclage placement for the management of inevitable abortion: a case report. Pregnancy & Child Birth. 2022;8(4):102-104. DOI: 10.15406/ipcb.2022.08.00269

Cervical cerclage placement procedure is one of the important approaches in the management of cervical insufficiency to prevent miscarriages and preterm labor. The purpose of this report was to show the importance of second transvaginal cervical cerclage placement in failed first emergency transvaginal cervical cerclage placement to prolong the gestation age towards term, thereby increasing fetal survival, prevent miscarriages and preterm births.

1% of all pregnancies and 8% of recurrent miscarriages are associated with cervical insufficiency.1,2 Cervical insufficiency is the painless spontaneous dilatation of the cervix without uterine contractions. It is one of the causes of preterm birth that lead to 35% of neonatal mortality.3 Some causes of cervical insufficiency include previous trauma to the cervix (conization procedures, lacerations during delivery, catheter mechanical dilatation during induction of labor) and congenital anomalies (Marfan syndrome, Ernlos-Danlos syndrome, exposure to diethylstilbestrol, cervical malformations).4 Treatment of cervical insufficiency is done by cerclage placement either by laparoscopic or transvaginal approach to prolong pregnancy, prevent preterm birth and avoid poor neonatal outcomes.5–8 High index of suspicion, early and accurate diagnosis of cervical insufficiency is critical so that necessary interventions of cervical cerclage placement is done to prolong gestation age, prevent preterm labor, neonatal morbidity and mortality.

Chinese female 33 years old, G1P0, 23weeks 6days gestation age by scan, referred from a local hospital due to cervical insufficiency with cervical length of 0.309cm discovered during routine antenatal visit. (Figure 1) She presented to our hospital with complaint of lower abdominal pain which started 5 hours prior to presentation. She denied any history of vaginal bleeding, vaginal draining or discharge. Patient also denied any history of fever, headache, dizziness, cough or diarrhea. Married, other history was not significant for any risk of cervical incompetence. On physical examination, significant findings were noted on vaginal and speculum examination with open cervix of 5cm and unruptured membranes bulging through the cervical os (Figure 2). An impression of inevitable abortion secondary to cervical insufficiency was made. Plan of emergency transvaginal cerclage placement, tocolysis/fetal protection with magnesium sulphate, oral progesterone, IV fluids for hydration, antibiotics for infection prevention and patient counselling was initiated within 1 hour after admission. The Shirodkar procedure was successfully performed without any complications after reducing the amniotic sac membranes back into the uterus (Figure 3).

Figure 2 Showing the opened cervix and bulging amniotic sac membranes.

Black arrow-cervix edge, Blue arrow-bulging amniotic membrane.

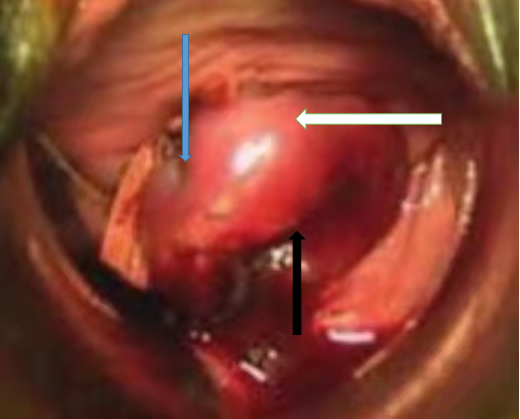

Figure 3 Showing the reduced membranes back into the uterus and sutured cervix.

Blue arrow-sutured cerclage tape, white arrow-ectocervix, black arrow-closed cervical external os.

Patient was discharged from the hospital 15 days after the procedure at 25weeks 1day gestation age. Patient was advised to stay longer in the hospital but declined. On the day of discharge, she had no complaints, her physical examination, fetal assessment and ultrasound findings were normal with closed cervical os and cervical length as shown in Figure 4. One day after discharge, patient returned back to our hospital for readmission with complaint of lower abdominal pain which started 2 hours prior to presentation. She had no other complaints. Vaginal examination revealed a loose cervical cerclage tape and protruding unruptured amniotic sac membranes. Other physical examination findings were normal. Patient underwent a second transvaginal cerclage placement (Shirodkar procedure) successfully with the continuation of antibiotics, tocolytic medication, magnesium sulphate and progesterone. Six days after readmission, patient went into spontaneous labor and the cervical cerclage was removed to ease progress of normal labor. Spontaneous vaginal delivery of male infant of 940g, Apgar score of 3, 7, 9 at 1, 5, 10 minutes respectively was achieved. The neonate was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for prematurity. Mother was discharged from the obstetric ward 4 days after spontaneous vaginal delivery. The neonate was admitted in the neonatal intensive care unit for 79 days after which he was discharged at 2.16kg.

Cervical insufficiency is treated by tying the cervix with a cerclage tape either laparoscopically or transvaginally in form of a purse string for good pregnancy outcomes. Research has shown that patients with deformed, short, scarred or absent cervices can benefit from laparoscopic or laparotomy cervical cerclage placement than transvaginal (Benson and Durfee, 1965; Oslen and Tobiassen, 1982; Novy, 1991; Cammarano et al., 1995; Anthony et al., 1997; Mackey et al., 2001; Zaveri et al., 2002). Untreated cervical insufficiency with exposed protruded amniotic fluid sac membrane increases the risk of exposure to the toxic environment which has bacteria that can trigger an inflammatory reaction leading to a miscarriage or preterm birth.9,10,11 Research has shown positive outcomes on the use of emergency transvaginal cerclage placement. Cerclage and a non-cerclage group were compared revealing 86.2% (25/29 cases) pregnancies in the cerclage group ended in live birth, compared with 42% (7/17 cases) pregnancies in non-cerclage group (P = .001) (relative risk [RR] 0.33, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.11-0.98).12 The procedure has also been found to prolong pregnancy for fetal maturity and favorable neonatal outcomes in women with cervical incompetence with success rate of 82.28% for live infants.13 Therefore, amniotic fluid sac reduction back into the uterus, transvaginal cervical cerclage placement, prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infections, use of magnesium sulphate as a tocolytic drug.14 and fetal neuro-protecting drug,15 IV fluids for hydration and progesterone.16 all play an important role in the overall outcome during the management of cervical insufficiency. Even if we had a successful outcome for our case, more research involving a large sample of cases to conclude on the efficacy of the second emergency transvaginal cerclage placement for the management of inevitable abortion.

Early identification and treatment of cervical insufficiency is critical in preventing preterm labor and reducing neonatal morbidity and mortality. We believe the following may play a positive role in the management of inevitable for favorable pregnancy outcomes:

More randomized controlled studies are required to see the extent for the benefits of performing the second emergency transvaginal cerclage placement for the management of inevitable abortion.

None.

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2022 Chanda, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.