International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9889

Research Article Volume 8 Issue 4

1School of nursing, Wolaita Sodo University, Ethiopia

2Department of biomedical science, Mizan Tepi University, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Temesgen Geta, School of nursing, Wolaita Sodo University, Sodo, Ethiopia

Received: September 26, 2022 | Published: October 19, 2022

Citation: Geta T, Mekine M, Kasa N. Satisfaction status and its associated factors on delivery service provided among women who gave birth at hawassa university comprehensive specialized hospital in southern Ethiopia 2022. Pregnancy & Child Birth. 2022;8(4):91-96. DOI: 10.15406/ipcb.2022.08.00267

Background: Despite the Ethiopian federal ministry of health implementing compassionate, respectful, and caring as one of the health sector transformation agendas to increase health service utilization, the level of maternal satisfaction with institutional delivery is still low and varies from region to region. In addition, no previous study was conducted in this study area. Therefore, the main objective of the study was to assess the level of women's satisfaction with institutional delivery services and associated factors among mothers who gave birth at Hawassa University's comprehensive specialized Hospital.

Methods and Materials: Institutional based quantitative cross-sectional study was employed from April to May 2022 at Hawassa University's comprehensive specialized hospital. A total of 265 women who came to delivery service were included in the study and systematic sampling techniques was used to select study participant. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect data. The data was entered into EPI Data 3.1 version and transported to SPSS version 25 for data analysis. Binary and multi-regression were done for predictor variables associated at p-value <0.05 with the dependent variable.

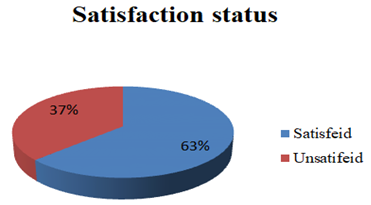

Result: A total of 265 mothers fully responded, making a response rate of 95.3%. This study found that 63% of study participants were satisfied and 37% of them were unsatisfied with the delivery and labor service. Participants' occupation, last pregnancy wanted, health conditions of the mother during and after delivery, media exposure to institutional delivery, total duration of labor, a surgical procedure done for women, the provider gives periodic updates on the progress of labor and explained what is being done and that to be expected were statistically associated with satisfaction status.

Conclusion: The study showed that the overall satisfaction of the women with the delivery service provided by health care providers in the study area was relatively low. Therefore, all stakeholders should take immediate and appropriate action on those identified factors.

Keywords: Satisfaction, institutional delivery, Hawassa university comprehensive specialized hospital, Southern Ethiopia

ANC, antenatal care; AOR, adjusted odd ratio; COR, crude odd ration; CI, confidence interval; HUCSH, hawassa university comprehensive specialized hospital; ID, institutional delivery; WHO, world health organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests satisfaction with health care service as the way of secondary prevention of maternal death and disease since satisfied women wish to accept and comply with service providers’ orders.1 It also suggests that mother’s satisfaction is an essential approach to maintain the quality and effectiveness of service provided. If there is no satisfaction, the provision of healthcare services does not improve the health of women and that of her child.2

Satisfaction is stated as the happiness that the patient/client gets when heath personnel offer service in the health institution as they wanted or when health care providers perform service according to their expectations.3 Satisfaction with institutional delivery (ID) service is also considered as the key approach to assess the quality of institutional delivery service among mothers who attend delivery service.4 Ideally, mothers who are not satisfied with the service provided by the health personnel are less likely to use health facility delivery service and not comply with ordered medical treatment to completion.3

Worldwide, above 810 mothers died within one day associated with pregnancy and childbirth problems in 2017. From these, 94% of the death occurs in Sub-Saharan African nations including Ethiopia. Most maternal mortality (MM) is preventable with timely management by a skilled health professional working in a health facility.5 WHO reported Ethiopia as one of the fifty countries; that have very high MM. Since 2000 Ethiopia has made some changes in MM.6 Ethiopian demographic health survey 2016 indicated that MM decreased from 676 in 2011 to 412 death per one hundred thousand live births in 2016.7 Labor and delivery time is the most essential period in which most maternal and neonatal health is maintained.8

Offering high-quality care for delivery and labor women was one of the major global strategies to prevent and reduce MM and neonatal death. It could prevent approximately one hundred thirteen thousand deaths of women by 2020.9 Literatures from different countries indicated that maternal satisfaction with institutional delivery services varies in different areas; 55% in Nepal (5); 81% in Nigeria;10 92.5% in Mozambique;11 and 60 to 80%12 in Ethiopia. Thus, to decrease maternal mortality related to delivery and improve the satisfaction of women with the delivery service utilization, health care providers should carefully focus on each mother’s labor.13 Mothers’ satisfaction status with institutional delivery can be influenced by the environmental condition of the health facility, age of the mother, educational level of mothers, duration of labor, availability of health care providers as well as w maternal waiting area, parity, and gender sensitivity.14–16

Though women’s satisfaction plays a key role in enhancing facility delivery service utilization, the magnitude of maternal satisfaction and influencing factors were not well identified. In spite of the Ethiopian federal ministry of health implementing compassionate, respectful, and caring as one of the health sector transformation agendas to enhance health service utilization, the level of women satisfaction with institutional delivery is still low and varies region and area to area.16,17 In addition, no previous study was carried out in the current site. So, this study aimed to assess the level of maternal satisfaction with facility delivery services and associated factors among mothers who gave birth at Hawassa University's Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (HUCSH).

Study area, period, and design

Hawassa is the capital city of Southern Ethiopia. Hawassa is 275 Km far from the capital city of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. The study was conducted at HUCSH, which is found in Hawassa city. The hospital is a tertiary level hospital serving around 12 million people in the Sidama and South Nation Nationality Peoples Region as well as the surrounding Oromia region. A cross-sectional study was conducted from April to March 2022.

Study population and eligibility criteria

Selected mothers who visited the HUCSH for delivery service and fulfilled inclusion criteria during the study period were the study population. All mothers who gave birth in HUCSH and who were discharged from the postnatal ward during data collection were included in the study. Mothers who were critically ill and unable to communicate were excluded from the study.

Sample size and sampling techniques

A total of 291 sample size for the study was determined by considering the following assumptions. 95% confidence interval (CI), 5% margin of error, and single population proportion formula through the assumption of the prevalence of satisfaction to institutional delivery was 74.6% from the study conducted at west Arsi in the Oromia region.18 Since the source population was less than 10,000, using the correction formula, the calculated sample was 253. By considering 10% of the non-response rate, the final sample size for the study was 278. The average monthly patient flow to delivery service for the 1st and 2nd quarters of 2021 was determined. Eventually, the subject was taken by systematic random sampling, and every 7th clients who came to Hawassa university referral hospital was recruited as a study unit till the total sample size for the study was obtained.

Measurements of satisfaction with institutional delivery care

Satisfaction refers to attaining the mother's needs or desires from the given delivery service.19 Satisfaction level of women was measured by all five measurement items in the Likert scale and answered as satisfied or dissatisfied. All mothers very satisfied and satisfied were categorized as satisfied whereas, very dissatisfied; dissatisfied, and neutral were categorized as dissatisfied.19 Those who responded as neutral were categorized as dissatisfied because they might represent a fearful expression of dissatisfaction which could be linked with the similarity of interview and service place, where women contacted with health care providers and received delivery service. Thus, women might be reluctant to express their dissatisfaction feeling on the service provided by the staffs. The overall satisfaction level of each item score was ≥75 %( ≥12 items) considered satisfied and whose satisfaction level was <75% (<12 items) were considered dissatisfied.14 There were sixteen items asked to assess mothers’ satisfaction.

Data collection procedure and analysis

Data was collected by structured questionnaire containing three components. The first component includes sociodemographic variables and the second part contains obstetric-related factors of the women. And the last component is designed to assess the level of satisfaction with institutional delivery. This component has 16 questions adapted from the previous study and presented using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfy.”19

Data was collected through face-to-face interviews. Based on communication skills with the client, three BSc nurses were selected for data collection. One health officer was recruited as supervisor. 1 day of training was provided to the data collector and supervisor regarding the objective, data collection tool, procedure, and interview methods that were supposed to be applied during the collection period. The selected participants were informed by the data collectors. From the selected participants, consent was obtained and the data was collected.

The questionnaire was prepared in English and then translated into the Amharic language by experts and again translated back to English to increase consistency. To keep completeness and consistency, data collectors were closely supervised before and during the data collection process by the supervisor. The supervisor supervised the correct implementation of the procedure and check the completeness and logical consistency after data collection.

The completeness and consistency of the data was checked. Then, it was coded and entered onto Epi Data 3.1. For further analysis data was exported to SPSS 25.0. Descriptive statistics of different variables were presented by frequency and percentage using tables and pie charts. A binary logistic regression test was used to compute COR with its 95% interval to test the associations between dependent and independent variables. The variables found to be P<0.25 in the bivariate analysis were taken as a candidate for multivariate analysis. Finally, Multivariate analysis with AOR was used to control possible confounders and to determine predictors of the prevalence of maternal satisfaction on institutional delivery. P- Value of < 0.05 was considered as the criterion for statistical significance. The study was approved by Wolaita Sodo University; College of Health Science Institutional review board, the reference number was WSU/IRB/1260/2022.

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

A total of 265 (95.3%) mothers fully responded to the interview. The mean age of the respondents was 28.91 with a standard deviation of 5.76 years and almost 75 % of mothers were within the age range of 21-35 years. 108 (40.8%), 215(81%), and 109 (41%) of respondents were government employees, married, and educated up to a diploma and above, respectively (Table 1).

Socio-demographic characteristics |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

|

Respondents’ age |

15-20 |

24 |

9.4 |

21-35 |

198 |

75.1 |

|

>35 |

43 |

15.5 |

|

Respondents’ marital status |

Married |

215 |

81.1 |

Single |

18 |

6.8 |

|

Othersa |

32 |

13.1 |

|

Respondents’ educational level |

Cannot read and write |

10 |

3.5 |

Can read and write |

34 |

12.8 |

|

Primary school |

43 |

16.2 |

|

Secondary school |

69 |

26 |

|

Diploma and above |

109 |

41 |

|

Respondent's occupation |

Governmental employee |

108 |

40.8 |

Merchant |

57 |

21.5 |

|

Housewife |

20 |

9.7 |

|

Private employee |

26 |

9.8 |

|

Othersb |

14 |

5.3 |

|

Respondents’ ethnicity |

Sidama |

106 |

40 |

Amhara |

53 |

20 |

|

Gurage |

34 |

12.8 |

|

Othersc |

72 |

27.2 |

|

Respondents’ residence |

Urban |

212 |

80 |

Rural |

53 |

20 |

|

Income level |

<5000ETB |

196 |

74 |

|

>=5000ETB |

69 |

26 |

Table 1 Socio-demographic characteristics of the women delivered in Hawassa university comprehensive specialized hospital (HUCSH), 2022(n=265)

a-widowed, divorced: b-daily laborer, unemployed, students: c-Wolaita, Oromo, Hadiya, ETB-Ethiopian birr.

Obstetric-related factors of the respondents

In this study, 201(75.8%), 139(52.5%), 258(97.5%), and 47.8% of study participants were multiparas, gave birth through spontaneous vaginal delivery, attended antenatal care (ANC) service, and accessed media information about the advantages of an institutional delivery through TV (Table 2).

Obstetric related factors |

Frequency |

Percent(%) |

|

Gave birth before |

Yes |

201 |

75.8 |

No |

64 |

24.2 |

|

Parity |

<=5 |

248 |

93.6 |

4-6 |

97 |

38.2 |

|

>6 |

47 |

18.7 |

|

Last pregnancy wanted |

Yes |

240 |

91.3 |

No |

25 |

8.7 |

|

ANC follow up |

Yes |

258 |

97.4 |

No |

7 |

2.6 |

|

Frequency of ANC |

<=4 |

198 |

76.7 |

>4 |

60 |

23.2 |

|

Place of ANC |

Hospital |

137 |

51.7 |

Health center |

87 |

32.8 |

|

Health post |

15 |

5.7 |

|

Othersd |

26 |

9.8 |

|

Media |

TV |

129 |

48.7 |

Radio |

58 |

21.9 |

|

Othersa |

78 |

29.4 |

|

Discussion with the provider on a place of last delivery |

Yes |

179 |

67.8 |

No |

87 |

32.2 |

|

Discussion with partners on the place of last delivery |

Yes |

192 |

72.5 |

No |

73 |

27.5 |

|

Hospital visit type |

New |

122 |

46 |

Repeat |

143 |

56 |

|

Labor started |

Spontaneous |

160 |

60.4 |

Induced |

105 |

39.6 |

|

The total duration of labor |

<=24 |

188 |

70.9 |

>24 |

77 |

29.1 |

|

Mode of delivery |

Spontaneous vaginal |

139 |

52.5 |

Assisted vaginal |

64 |

24.2 |

|

Cesarean section |

62 |

23.4 |

|

Time of delivery |

Day time |

164 |

61.9 |

Night time |

101 |

38.1 |

|

Time of stay before delivery |

<=24 |

247 |

93.1 |

>24 |

18 |

6.8 |

|

Time stay after delivery |

<=24 |

235 |

88.7 |

>24 |

30 |

11.3 |

|

Outcome of delivery |

Alive |

258 |

97.4 |

Died |

7 |

2.6 |

|

Any Procedure done |

No |

64 |

24.2 |

Yes |

201 |

75.8 |

|

Informed consent taken |

Yes |

180 |

89.6 |

No |

21 |

10.4 |

|

Maternal health after delivery |

Normal |

219 |

82.6 |

Had complicated |

46 |

17.4 |

|

Total distance to reach the hospital in a minute |

<=30 minute |

123 |

46.8 |

31-60 minute |

108 |

40.0 |

|

61-120 minute |

19 |

7.2 |

|

>120 |

16 |

6 |

|

Table 2 Obstetric-related factors of the respondents at HUCSH in southern Ethiopia, 2022(n=265)

d-private clinics, private hospitals: TV-television

Health care provider-related factors of the respondents

Seventy and around 62 percent of the respondents received respectful care, and got information on what was being done and what to expect from the delivery care service, respectively. During service provision, 157(60% of) providers used physical force and showed abrasive behavior (Table 3).

Health care provider-related factors |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

|

Delivery attendant |

Midwife |

188 |

70.9 |

General practitioner |

49 |

18.5 |

|

Nurse |

21 |

7.9 |

|

Health officer |

7 |

2.6 |

|

Gender of attendant |

Male |

112 |

42.3 |

Female |

153 |

57.7 |

|

Number of attendants |

<=3 |

210 |

79 |

>3 |

55 |

21 |

|

Remain with women whenever possible |

Yes |

175 |

66 |

No |

90 |

34 |

|

Explains what was being done and what to expect |

Yes |

163 |

61.5 |

No |

102 |

38.5 |

|

Gives periodic updates on the progress of labor |

Yes |

142 |

53.6 |

No |

123 |

46.4 |

|

Gives respectful care |

Yes |

185 |

69.8 |

No |

80 |

34.2 |

|

Used physical force or abrasive behavior |

Yes |

157 |

59.2 |

No |

108 |

41.8 |

|

The utilized maternity waiting room |

Yes |

64 |

24.2 |

No |

201 |

75.8 |

|

Table 3 Health care provider-related factors of the respondents at HUCSH in southern Ethiopia, 2022(n=265)

Overall satisfaction

This study found that 63% of study participants were satisfied and 37% of them were unsatisfied with the delivery and labor service provided by health care providers in HUCSH (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Overall satisfaction level among participants at HUCSH in the southern part of Ethiopia, 2022.

Factors associated with satisfaction with institutional delivery

This study identified nine statistically significant variables including occupation status[AOR= 6, 95% CI (1.2-32), p = 0.004], the wanted status of last pregnancy[AOR= 7.2, 95% CI (1.6-33.6)), p = 0.013], conditions of the mother during and after delivery[AOR= 3.6, 95% CI (1.-8.9), p = 0.005], media exposure to ID[AOR= 2.7, 95% CI (1.2-3.6), p = 0.000], total duration of labor [AOR= 0.28, 95% CI (0.2-0.5), p = 0.000]. And the others displayed in table below (Table 4).

Factors |

COR |

AOR(CI) |

p-value |

|

Respondent's occupation |

Governmental employee |

3.96(0.13-1.23) |

6(1.2-32) |

0.004 |

Merchant |

2.8(0.6-13.7) |

4.2(0.8-23.4) |

0.103 |

|

Housewife |

0.2(0.1-0.69) |

4.9(0.9-26.8) |

0.63 |

|

Private employee |

4.1(0.8-19.4) |

6(0.9-35.7) |

0.53 |

|

Othersb |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Last pregnancy wanted |

yes |

6.9(1.6-30.1) |

7.2(1.6-33.6) |

0.013 |

No |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Health status of the mother at last delivery |

Normal |

4.0(1.7-9.24) |

3.6(1.-8.9) |

0.005 |

Complicated |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Media exposure |

TV |

2(1.0-4) |

2.7(1.2-3.6) |

0.000 |

Radio |

1.5(0.7-3.3) |

1.7(0.7-3.6) |

0.000 |

|

Otherse |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

The procedure is done for women |

Yes |

0.4(0.2-0.72) |

0.35(0.2-0.7) |

0.004 |

No |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Explained what was being done and to expect |

Yes |

4.1(2.3-7.4) |

3(1.5-6.4) |

0.02 |

No |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Gives periodic updates on the progress of labor |

Yes |

3.8(2.2-6.6) |

4.4(2.3-8.4) |

0.00 |

No |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Total labor duration |

>24 |

0.3(0.2-0.45) |

0.28(0.2-0.5) |

0.00 |

<=24 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Table 4 Factors associated with satisfaction institutional delivery among delivery attendants at HUCSH in Sothern Ethiopia, 2022(n=265)

e-telegram, Facebook, health care providers; b-unemployed, students, daily laborer

According to this study, the overall satisfaction of mothers with institutional delivery services was 67%, which was lower than the studies carried out in Southern part(82.3%)20 and Tigray (95%).21 The difference may be due to uniqueness in methodology, the expectation of mothers, the quality of delivery service provided, and the procedure used to compute overall satisfaction.

The wanted status of last pregnancy was a significant predictor of satisfaction. Finding from the study indicated that women who wanted their last pregnancy were 7.2 times more likely to be satisfied with delivery service compared to their contrast group. This might be related to the historical process of acquiring conception, potential challenges to care for the newborn baby, familiarity with health institutions before delivery service, family acceptance, and socio-cultural reasons.

Another explanatory variable was the total duration of labor. Mothers whose labor stayed more than 24 hours were

72% less likely to satisfy on institutional delivery compared with those who stayed less than or equal to 24 hours. This study was supported by studies done in Wolaita and Amhara21,22 A randomized controlled trial of active management of labor conducted in Auckland20 and New Zealand23 reported that the practice was related to the reduction of labor time and a postpartum report of longer labor than expected was strongly associated with a reduction of maternal satisfaction. This could be due to staying a prolonged period with labor pain as it is a vulnerable time, could affects satisfaction level.

Finding from the study indicated that those study participants whose service provider gave periodic updates on the status and progress of labor and delivery were 4.4 more likely to be satisfied than those who were not and those who gave birth at areas where care providers explain what is being done and to expect during labor were 3 times more likely to be satisfied compared to those who were not provided. This finding was similar to study done in Nepal24 and Ethiopia.25 The possible explanation might be providing adequate and updated information about their health status could make them happier and enhance cooperation with health care providers.

The study found that mothers who have normal health status during and after delivery were 3.6 times more likely to be satisfied with delivery service compared to their opposite group. Likewise, a study done in Ethiopia revealed that normal health status during and after delivery was 5 times more likely to be satisfied with delivery service compared with women who had complicated health status.20 The possible explanation might be complications occurred during and after delivery lead to stress and make them unhappy; this contradicts mothers’ satisfaction status.

Occupational status was the other variable positively and significantly associated with satisfaction with institutional delivery. Governmental employees were 6 times more likely to be satisfied with delivery service compared to other groups. The possible reason might be it was a common problem in a country like Ethiopia; most health care providers give more attention and respectful care to educated personnel and famous people, which could affect satisfaction levels. In addition, It could be linked with the governmental employee easily understands the health providers’ orders and comply with them. Thus, women would be happier and to be satisfied with delivery service provided.

This study showed that a mother being done surgery was negatively associated with a satisfaction level of institutional delivery. Mothers being done surgical procedures were 65% less likely to be satisfied with ID compared with those who were not. The possible reason might be stress and pain felt secondary to the surgical procedure, and its potential outcome on the mother. Thus, this could contribute to dissatisfaction with the delivery service provided.

This study indicated that those women whose health care providers explained what was being done and what to expect were three times more likely to be satisfied with delivery service compared to their opposite groups. Pieces of evidence from Ethiopia26 and Nepal27 suggest that providing inadequate and/or no information on the service going to be done and what to expect was a major cause that negatively affect the satisfaction status. Thus, the client who was informed before conducting any service and what to expect after the service was happier and satisfied with the service provided.

Women who had had television media exposure on institutional delivery were 2.7 more likely to be satisfied with delivery service compared to other media users. Even though it is not easy to identify the cause and effect, the study showed that delivery attendants who had exposed to media, particularly television were tended to have better satisfaction with the delivery service they received. Having exposure to media may be related with better knowledge and awareness of the health service and adaptation to the health facility.

A long time relapse after delivery might result in recall bias and absence of inferring causality related with cross-sectional study are among the limitations of the study. Regarding the strength of this study, being an institutional based study and having adequate sample size could help to generalize the study.

Overall women' satisfaction status with delivery services provided in the HUCSH was relatively low. The total duration of labor, surgery performed for women, participants' occupation, last pregnancy wanted, conditions of the mother during and after delivery, media exposure to ID, the provider gives periodic updates on the progress of labor, and explained what is being done and what to be expected were identified as associated factors. So, we recommended that all service providers and hospital top managers should address these predictors that affect the women’ satisfaction status and should improve the quality of delivery service.

Consent for publication is not applicable.

We declare that we have no competing interests.

No funding was received .

TG: Conceive data and designed the study, supervised the data collection, performed the analysis and interpretation of data, drafted the manuscript, and finally approved the revision for publication. TG had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of data and the accuracy of data analysis. NK and MM assisted in designing the study and data interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. .

We would like to express our appreciation to Wolaita Sodo University, College of medicine and health sciences, and school of nursing for continued support and follow-up. We would like to thank respondents for their cooperation during data collection and the staff for their support by providing the number of mothers who gave birth in the last six months at the hospital.

©2022 Geta, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.