International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9889

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 5

NICU, Luton and Dunstable University Hospital, England

Correspondence: Claudia Chetcuti Ganado, NICU, Luton and Dunstable University Hospital, 16 Varrier Jones Drive Papworth Everard CB23 3GJ, England

Received: September 05, 2021 | Published: September 21, 2021

Citation: Ganado CC, Dabbour S, Fatin Y. Improving the effectiveness of the referral process in a tertiary NICU using lean methodology concepts. Int J Pregn & Chi Birth. 2021;7(5):122-127. DOI: 10.15406/ipcb.2021.07.00241

Aim: To reduce the administrative time trainees spent when completing a patient referral to specialist teams in a tertiary Neonatal Intensive care setting. Methods: We designed a pre intervention and post intervention questionnaire completed prospectively by trainees describing the tasks they needed to undertake to complete a referral, the time perceived as ‘wasted’ and suggest potential solutions over a 2 month period between 1st June 2020 and 1st August 2020. We used Lean methodology to identify waste as steps that did not add value to quality patient care. We designed a NICU referral directory containing the standard operating steps, the appropriate proformas and contact details of receiving unit, a process algorithm and a collective consultant email address.

Results: Our project achieved a reduction in the median time to complete a referral from 27.5 minutes to 6 minutes (p = 0.0087). The time perceived ‘wasted’ by trainees was reduced from 20 minutes to 0 minutes (p=0.006). Conclusion: Our project is a simple intervention and supports using Lean methodologies to identify waste and bring about quick improvements without significant capital investments. We demonstrate how front line staff can be engaged in identifying inefficiencies, suggest solutions which help in the successful adoption and sustainability of quality improvements.

Our tertiary NICU in the East of England has approximately 900 admissions per year. We do not have specialist and surgical facilities on site and neonates needing input into these areas are referred to a quaternary hospital in London. Referrals for specialist input are a significant role in our day-to-day practice. The commonest referrals are for surgical management of necrotising enterocolitis, gastrointestinal malformations, cardiac interventions, and neurosurgical interventions. Common medical referrals are to neurology and neuromuscular teams, endocrine and hyperinsulinism teams, respiratory teams and neuroradiologist opinions.

Background

Ensuring effective transfer of information is paramount in the referral process. The importance of both intra and interhospital communication in patient safety cannot be understated. The impact of communication errors in patient safety is well documented. In a retrospective review of 14,000 in-hospital deaths, communication errors were found to be the lead cause, twice as frequent as errors due to inadequate clinical skill,” notes a 2006 study in the Clinical Biochemist Review.1 This also spills over to malpractice costs to the healthcare organisations. Additionally, inability to access patient information may cause delay in treatment which may have an impact on patient flow and capacity, duplication of tests and second opinions. Information flow from referrer to recipient is further hindered by the unavailability of common information transfer systems and varying practices of referral pathways at inter or even intra organisational levels.

The impact on clinician time to ensure adequate information transfer can be huge. This in turn will impact on young clinicians training, workload and burnout. The quality of care a patient receives is also influenced by the capacity and resilience of the workforce to be at the patient bedside. The process of calling other hospitals to access results or making an already existing referral impacts on the workload of the referring clinician, the receiving clinicians but also spills over to other healthcare workers such as secretaries and switchboard operators. The impact this has on the ineffective use of human resources and duplication of tests is difficult to quantify as is the impact on clinician training and quality care to the patient even in the absence of errors. Although the importance of communication is widely recognised and attempts at creating the technology infrastructure have been attempted since the 1960’s,2 the progress has been slow and significant barriers have emerged particularly in relation to the interoperability of these systems.3

Rationale

Our unit currently uses paper documentation which is subsequently scanned onto an electronic system after patient discharge. This creates a time lag for accessing scanned notes by receiving clinicians. Information transfer requires adequate referral documentation. Referral documentation systems and processes differ between different specialities. External referrals to quaternary hospitals are even more complex. Information transfer reaching the correct clinician and using the correct proformas and contact emails often requires several different telephone conversations and email exchanges between clinicians, secretaries and NICU matron in both referring and receiving units which also often go through switchboard and the paging system.

Although referrals are common in our unit the occurrence of a referral to the same speciality is not frequent enough for knowledge consolidation of the referral process. This is further exacerbated by 4 monthly trainee rotations. Trainee shift working patterns, Consultant rotation, differing information flow systems create the right breeding ground for potential communication failures and duplication of referrals. This impacts on both referring and receiving clinician time, with conflicting information given to different clinicians.

Speciality trainees are an expensive and invaluable resource to support patient care in the acute setting of an intensive care unit. The fast-paced nature of patient status on the intensive care unit also means that interventions and procedures are often time critical. Additionally, delay in the referral processes can further impact on patient safety.

Almost invariably, a trainee starting the referral process will need to go through the process of finding the correct way to do it, a process that can take several minutes. This means that trainees invariably spend a significant amount of time on jobs that are not adding value to quality patient care.

Aim

The primary aim of our project was to improve the efficiency of the referral process by reducing the time spent by trainees on jobs that were not directly patient-facing. The aim was to reduce the time spent on these jobs by at least 30%. The secondary aims were to create a failsafe audit trail so that duplication of work did not occur, and to ensure that all referrals and associated communication flowed seamlessly, no matter which team was on shift, throughout the journey of the patient until discharge.

Phase one

The first step of this phase was designed to help understand the extent of the problem and invite input from frontline staff as to how this could be improved. A prospective questionnaire was designed for trainees to complete for every patient referral they undertook in real time. The questionnaire was designed to capture the total time spent for completing a particular referral, the time perceived to be ‘wasted’ during this process and the steps taken to complete the process from start to finish. The questionnaire was also designed to capture whether trainees were aware of the standard operating process for referral, whether all the steps taken were necessary and asked for suggestions on how this process could be improved. This questionnaire ultimately helped us map the process taken for a trainee to complete a referral from start to finish. Referrals were classified as external or internal depending on whether the referral was to a clinician working outside or within our trust.

Phase two

Planning and intervention

The process map revealed how some of the steps taken to complete the referral were not adding value to quality patient care. We applied the LEAN methodology principles to inform our change ideas to improve the efficiency of the process.

Our drivers and change ideas are depicted in Figure 1. To reduce the time spent on administrative tasks, we created a referral directory on a shared drive. This contained all the referral operating processes for the more common referral pathologies encountered on the neonatal unit. We created folders for both 'Internal' and 'External' referrals, and in each of these a subfolder with the particular pathological diagnosis. The subfolder for each pathology contained

We designed a referral proforma to consolidate communication between different teams and create a failsafe for closing the loop prior to patient discharge. The proforma was incorporated into the admission packs. An e referral repository was created in line with the directory so any online referral proformas could be stored for each patient. We created a collective consultant nhs.net email address, and trainees were instructed to copy this address into any referrals, specialist advice and email communications with other specialities using the patient’s name and NHS number in the subject heading. To help with tracking referrals, consultants were encouraged to categorise these emails by type under 'advice', 'referrals' or 'results' using the Microsoft Teams facility in their inbox.

Phase three

Creating awareness:

The new process was formally launched during our weekly journal club meeting, via our quality governance meeting, and by reminder emails. The referral process also forms part of new trainee induction.

We created a process algorithm to help memory recall ASCC: Access- the referral directory; Store – Patient information in referral e-repository; Complete- the referral proforma and Communicate- to all consultant team via collective email.

The consultant nhs.net email address has been printed and displayed beneath each computer monitor on the neonatal unit as a reminder to copy all consultants into any email correspondence regarding patients.

The project 'champion' monitored engagement and provided individual feedback. The project team provided regular updates on additions to the directory.

Trainees were asked to complete a pre and post- intervention questionnaire prospectively. Data was collected over a one-month period between 1st June 2020 and 1st August 2020.

The median time taken to complete ‘all type’ referrals in minutes improved from 27.5 (10-95) to 6 (3-45) p (T<=t) one tail 0.008. The time perceived wasted in ‘all type’ referrals reduced from a median of 20 minutes (5-65) to 0 minutes(0-30) p(T<=t) 0.006 (Table 1).

|

|

Median time to complete a referral from start to finish (minutes) |

|

|

Median time perceived wasted while completing the referral (minutes) |

|

|

|

Pre |

Post |

P(T<=t) one tail |

Pre |

Post |

P(T<=t) one tail |

|

|

n=14 |

n=14 |

0.0087 |

n=14 |

n=14 |

0.006153 |

|

|

Median |

27.5 |

6 |

20 |

0 |

||

|

Range |

(10-95) |

(3-45) |

|

(5-65) |

(0-30) |

|

Table 1 Median time and range in minutes pre and post intervention for all type referrals to be completed

This trend was consistent even within subgrouping the referrals into internal and external. Pre-intervention, none of the trainees who completed the questionnaire had knowledge of how to undertake the referral process. The median time to complete external referrals was 32.5 minutes (range 15-95) The median time perceived ‘wasted’ was 20 minutes (range 5-60). For internal referrals, the median time to completion was 22.5 minutes (range 10-75) and time perceived ‘wasted’ was 17.5 minutes (range 5-65). Unnecessary tasks for referral completion were undertaken in 11 of the 14 referrals. Confirmation that the referral had reached the intended clinical team was done in 10/14 referrals. In 2/14 cases, referral required follow up.

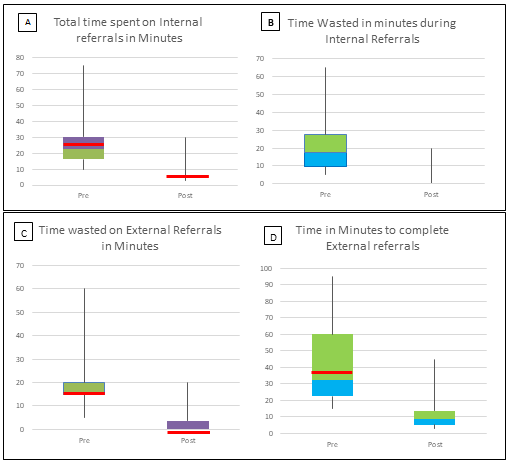

Following the intervention, the median time for completing an external referral decreased from a median of 32.5 minutes (range 15-95) to 8.5 minutes (range 3-45). The median time taken to complete an internal referral decreased from a median of 22.5 minutes (range 10-75) to 5 minutes (range 3-30) (Figure 2).

The time perceived as ‘wasted’ by trainees decreased from a median of 20 minutes (range 5-60) to 0 minutes (range 0-30) for external referrals and from 17.5 minutes (range 5-65) to 0 minutes (range 0-30) for internal referrals (Figure 2). This improvement was also observed when referrals for identical conditions were compared pre and post intervention (Table 2). Trainee awareness of referral process increased from 0% (0/14) to 86% (12/14) post-intervention. Referral receipt confirmation increased from 78% (11/14) to 100% (14/14) post-intervention.

Figure 2 Box plots for time taken in minutes pre and post intervention n=14. A+B: Internal referrals.

C+D: external referrals.

|

Relation to intervention |

Type of referral |

What |

Total time wasted in minutes |

Total time taken to complete the referral in minutes |

|

Before |

External |

PDA ligation |

20 |

60 |

|

After |

External |

PDA ligation |

0 |

10 |

|

Before |

External |

Surgical review |

20 |

25 |

|

After |

External |

Surgery |

0 |

5 |

|

Before |

Internal |

Physiotherapy |

5 |

10 |

|

After |

Internal |

Physiotherapy |

0 |

5 |

|

Before |

Internal |

opthalmology referral |

20 |

25 |

|

After |

Internal |

Opthalmology |

0 |

5 |

|

Before |

External |

Genetic referral |

10 |

15 |

|

After |

External |

Genetics |

0 |

5 |

|

Before |

External |

Plastics |

15 |

30 |

|

After |

External |

Plastics |

5 |

15 |

Table 2 Time taken to complete like for like referrals pre and post intervention in minutes

The questionnaire also captured qualitative feedback. Problems highlighted pre intervention were unclear referral processes, spending considerable time looking for proformas or waiting for switchboard. Post intervention feedback highlighted a clear and effective process.

The transfer of information between clinicians and hospitals has been recognised to be ineffective since the 1960’s.1,4 The patient journey may involve several professionals, requiring a constant information flow between the different people, at different stages of the patient journey. Its impact on patient safety has been well-documented1,4 and since errors from ineffective communication are preventable, hospitals have a duty to ensure an effective communication system. As nicely described by Enrico Coiera ‘If information is the lifeblood of healthcare, then communication systems are the heart that pumps it.1

The ideal interoperability as defined by the KLAS report is "consistent access to needed patient information in an easily-located and viewable place within the healthcare record”,5 in that different professionals and different hospitals use a singular technology and follow standard protocols for communication including referrals. Despite the recognition of the importance of effective communication gathering, processing and sharing, when compared to other industries, the healthcare section has lagged behind. In the UK, whilst interoperability of systems has been on the healthcare agenda for several years, its progress has been very slow.6

Our project was a simple yet effective way of mitigating the interoperatibility issues that still exist in our day-to-day functioning in healthcare. The lack of a standard process necessitated trainees to spend time finding out the right ways to communicate. This impacts on the capacity and resilience of clinicians to undertake patient care. Additionally, contacting clinicians to understand the administrative aspects of a referral process increases cognitive load whish may lead to errors from tasks being forgotten or not completed.1 This spilled over to other departments and contributed to increasing call queues when contacting switchboard operators. Our project resulted in a significant reduction in the time spent by trainees completing a referral process. For external referrals, we demonstrated a 74% reduction in the time taken to complete a referral.

In planning our interventions, we used the lean methodology concepts. Table 3 summarises the Components of Lean and how these applied to our project. Lean management systems focus on understanding the needs of the customer and then improving the value stream by removing the waste. Waste is best defined as anything that uses resources but does not contribute to adding value for the customer. Lean is about making people work smarter but not necessarily harder to deliver improved results.7 The common improvements identified by Healthcare organisations that have successfully implemented Lean Management systems include time- savings, timeliness of services, improved productivity, and several quality aspects including reduction in errors or mistakes and improved staff and patient satisfaction.8 Lean also empowers staff to identify problems and engage in continuous improvement. Our pre intervention questionnaire empowered trainees to identify the problem and come up with potential solutions which gave them ownership. This in turn led to engagement and sustainability. Once trainees identified the problem they took onus in developing the directory further when undertaking a referral for conditions that were not in the directory therefore continuing to build on its content. Our project delivered improvement in a relatively short timescale and without the need for capital investment as has been shown in other Lean interventions.7 The questionnaire was designed to identify unnecessary tasks to undertake the referral process which enabled us to map the typical process and identify steps that did not add value and were perceived ‘wasted’. Our project achieved a 100% reduction in the perceived time wasted for both the internal and external referrals among all trainees. Reduction of steps in a process was similarly reported by other authors.9–11

|

Component |

Context |

Mechanism |

Outcome |

|

Methods to understand processes in order to identify and analyse problems Process mapping |

Trainees believed it is part of their ‘normal’ process to spend a long time in formulating a referral. It was not questioned how this could have been done in a smarter way. Highlighting steps in the process |

Realising there is a problem and extent of the problem through quantifying time spent on non-added value processes |

Awareness of the problem engaged in adoption of change and in a culture of continuous improvement and for adopting further changes and dynamic context |

|

Methods to organise more effective and/or efficient processes Process orientation Elimination of waste availability of steps in process Directory concept |

The different processes required by different specialities and lack of a standardised system necessitated checking each time a referral was made Referrals were not frequent enough for trainees to master the process steps Frequent rotation led to the problem recurring |

Suggestions on what needed to be done |

Staff feel part of the change- Encouraged adoption Staff aware of the benefits – Sustainability Directory concept with ease of access – Clarity where to access information

|

|

Enhance adherence to standard procedures Induction training SOP mnemonic |

No clear processes or education of looking for information led to a lengthy process as trainees tried different processes of obtaining the information |

Incorporation into induction to highlight the importance of the information availability |

Improved awareness and sustainability with different teams Ease of adoption and memory recall |

|

Team approach to problem solving and rapid process improvement events |

Trainees not questioning their work load, ‘too busy to improve’ |

Trainees suggesting what needs to be done Simple concept and solution |

Ownership of improvement responsibility Awareness that small changes can bring about improvement with no capital investment or complex changes to infrastructure |

Table 3 CIMO table explaining the components of Lean used in our project

To promote awareness, we used several dissemination tools including formal launch presentations, email reminders and individual feedback through real time ‘nudge’ to follow the process by our ‘champions’. Its incorporation into induction ensured that subsequent trainees were fully aware of the process. Retention of the information was facilitated using the human factor concepts. Our process algorithm acted as a memory recall to seamlessly guide the flow of communication through the right channels. Standardisation of practice, a single common information storage folder allows the know-how to embed its roots amongst staff and become a part of ‘what we do’.

Establishing a standard process for communication to all consultants and using a referral proforma as a ‘care bundle’ reduces variability of the individual practices some of which may lead to suboptimal communication. Although it was difficult for us to objectively demonstrate improved communication the adoption of these into our routines supports improved communication. Consultants can access online information exchanges at any point in the patient journey.

Challenges and weakness

The major challenge was to encourage the trainees to complete the proforma in real-time, especially during the busy hours of the morning. This was facilitated by the hands-on approach of the project team.

The major weakness of this project is that we compared same type referrals undertaken by different trainees which may introduce bias due to the influence of trainee competency and time management skills and the small number of like for like referrals questionnaire responses collected.

Our project uses a combination of Lean methodologies and human factor principles to mitigate the effects of poor hospital communication systems on clinician time and cognitive workload. Our project also supports the use of Lean in bringing about quick improvements with no capital investment. It demonstrates how engaging front line service providers to identify a problem and suggesting potential solutions can encourage a culture of continuing improvement.

None.

We have no conflict of interest in this article.

None.

©2021 Ganado, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.