International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9889

Research Article Volume 8 Issue 3

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Alex Ekwueme Federal University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

3Nigerian Institute of Medical Research, Nigeria

4Health, Environment and Development Foundation, Nigeria

Correspondence:

Received: May 10, 2022 | Published: August 4, 2022

Citation: Olamijulo JA, Agboeze J, M. Afolabi B. Gynecological co-morbidity, chronic illnesses and infectious diseases among black African women with primary or secondary infertility: should we be worried about hepatitis? Pregnancy & Child Birth. 2022;8(3):71-78. DOI: 10.15406/ipcb.2022.08.00264

Introduction: Female infertility may not occur alone but could be associated with other health conditions. Overlooking these health conditions during clinical assessment of women who present with primary or secondary infertility may not bring desired results of achieved pregnancy.

Objective: To determine the frequency and relative risks of certain chronic illnesses such as hypertension and diabetes, infectious diseases such as hepatitis and other gynecological diseases such as uterine fibroid and endometriosis in women with primary and secondary infertility taking into consideration their age groups and body mass index.

Study design: This was a retrospective study carried out at a tertiary health care facility in Lagos Nigeria.

Methods: Records of patients who consulted for the management of infertility were retrieved for analysis.

Result: The overall prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, cancer and asthma in all patients were 9.6%, 6.8%, 0.8% and 0.4% respectively. Among the infectious diseases, hepatitis B occurred most frequently at 19.1%, more among women with SI (28.0%) than PI (13.9%). The most prevalent gynecological diseases as co-morbidity were uterine fibroid (32.7%) and endometriosis (11.2%). Pooled analysis showed that there was a significant variation in the distribution of Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) (Pearson’s χ²=10.14, P-value=0.02) relative to age, no significant distribution of any disease relative to body mass index (BMI) in Kg/m2, significant distribution of intrauterine adhesion relative to age (years) and BMI among those with PI (Pearson’s χ²=9.80, P-value=0.04) but not in SI. Significant correlations were observed between infertility and hepatitis (r=0.17, P-value=0.006, 95% CI= 0.06, 0.36) and between infertility and fibroid (r=0.1868, P-value=0.003, 95% CI=0.07, 0.32).

Conclusion: Through this study it is concluded that women with history of primary infertility are more at risk of diabetes, endometriosis and PCOS more than those with SI; conversely, those with SI are more at risk of hypertension, hepatitis, fibroid and adenomyosis. Gynecologists and fertility experts in sub-Saharan Africa should probe for these diseases in each patient who presents with infertility, after excluding male factor as contributing to female infertility. Early diagnosis of these diseases and others among infertile or sub-fertile women can minimize pain and reduce cost of hospitalization and also minimize the number of patients with unexplained infertility.

Key words: hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hepatitis b, uterine fibroid, endometriosis; infertility, black women, sub-saharan africa

Infertility has been described as a “disease” of male or female reproductive system defined by failure to achieve a pregnancy after twelve months or more of regular, unprotected sexual intercourse.1 It is estimated that, globally, as low as 48 million and as high as 186 million individuals are affected by infertility.2-4 A range of extra uterine (endocrine, abnormalities of the ovaries), intrauterine (uterus, fallopian tubes), intracavitary (abnormalities within the uterine cavity) and infectious diseases (Tuberculosis, hepatitis) among other, may be responsible for female infertility, which could be primary (never achieved pregnancy) or secondary (had achieved pregnancy at least once). Adequate clinical fertility management includes prevention, diagnosis of hindrances to get pregnant and removal of such hindrances and application of appropriate treatment to reverse infertility. According to WHO, equal and equitable access to fertility care remains a challenge in most countries; particularly in low and middle-income countries.1 certain conditions constitute hindrances to fertility, either as causative or as co-morbidity with infertility or both. Among these are certain chronic medical diseases such as hypertension and diabetes. For example, chronic high blood pressure prior to pregnancy has also been linked with (i) poor egg quality (ii) excessive production of estrogen (iii) difficulty in embryo implantation and (iv) miscarriage. Those that high blood pressure can contribute to their infertility or lower their chances of getting pregnant are women who are (i) aged above 35 years, (ii) overweight or (iii) obese.5 In a study on Infertility and risk of hypertension, Farland et al.,6 reported no apparent increase in hypertension risk among infertile women or those who previously underwent fertility.6 Another chronic illness that can cause infertility is diabetes of either type. Although a woman may get pregnant with proper control with gycemic medications, remaining pregnant for the entire duration may pose a major problem, especially if she has had diabetes for a prolonged period.7

Diabetes is known to impact female and male fertility by causing hormonal disturbances with delayed or failed implantation and/or conception as consequences as well as poor sperm and embryo quality and damaged genetic mutations and deletions8 A study reported a 20% greater risk of developing diabetes among women with a history of infertility compared with those without such a history, after adjusting for adjusting for age, lifestyle factors, marital status, oral contraceptive use, family history of diabetes and BMI.9 Other health conditions that may cause infertility are uterine fibroid and endometriosis. Uterine fibroid is present in about 33% of women of reproductive age10 and in Nigeria; there is a relatively high prevalence of symptomatic fibroid in women who presented with infertility.11

Despite the fact that between 5% to 10% of female infertility linked with uterine fibroid, uterine fibroid is reckoned to be the exclusive constituent for infertility in only 1% to 3% of cases.12,13 Endometriosis, the presence of endometrial-like tissue (glands and stroma) outside the uterus, which induces a chronic inflammatory reaction, scar tissue, and adhesions that may distort a woman’s pelvic anatomy and primarily found in young slender women.14 An enigmatic disease, endometriosis, impacts about 10% of women in child-bearing age causing pain and infertility. Approximately 50% of women diagnosed with endometriosis are infertile15 while about 20% of infertile women have endometriosis.16 Further, Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), an endocrine disorder in which women have higher than normal levels of testosterone (hyperandrogenism), is a common condition that can reduce or prevent female fertility. It is a condition in which a large number of cysts develop on the ovaries and is associated with irregular periods (oligomenorrhea) or absent periods (secondary amenorrhea) thus an ovulation or irregular ovulation.17 PCOS is particularly associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes. The prevalence of PCOS in the Chinese community population was 5.6%18 and it occurs in one in six infertile Nigerian women.19

Obesity plays a vital role in hyperandrogenism, hyperinsulinemia, and the development of PCOS,20 Infectious diseases, such as Hepatitis B virus (HBV), have also been known to negatively affect fertility. The World Health Organization (WHO) documents that African, Asian, and South American countries have carrier rates as high as 8%, with Africa, south of the Sahara responsible for 20% of the global burden.21 For example, one source suggested that HBV infection in either partner is associated with tubal infertility and that HBV infection in either partner probably increases the risk of pelvic infection in female partner through impaired immune response to sexually transmitted infections, with consequent tubal damage and infertility.22

HBV infection in women has been associated with increased risk of tubal and uterine infertility and in men, it has been linked with increased risk of tubal infertility in their partner, due to the HBV virus lowering the woman’s immune system and increasing the chance of pelvic infection.23 It might not be too challenging for gynecologists to diagnose infertility in sub-Saharan Africa but exploring definitive cause(s) and risk factors for infertility, and removing cause and ameliorating the condition such that the patient becomes pregnant may be a Herculean task. Considering the many causes of female infertility which a woman can be exposed to and considering the dearth of local data on some of these conditions, the study aimed to calculate the risk of co-morbidity with other gynecological illnesses, chronic illnesses and infectious diseases that co-exist with either primary or secondary infertility among Black Women in sub-Sahara Africa. The study intended to list diseases most prevalent in primary or secondary infertility relative to age and body mass index and to evaluate the correlation and linear regression of primary and secondary infertility against these diseases for any significant association.

In 2018 and 2019, a total of 1421 and 1590 gynecological cases were seen, respectively, making a total of 3011. In each of these years, 202 (14.2%) and 206 (13.0%) cases (408, 13.6%) of female infertility were recorded at a tertiary health facility in Nigeria. Of this number, 251 (61.5%) cases of female patients attending weekly gynecology clinic were randomly selected and analyzed in this study. The tertiary health facility serves a population of approximately 5 million people not only for obstetrics and Gynecology but for all other clinical, sub-clinical and biomedical departments. Patients patronizing this facility are from all strata of the society. Patients are also referred from other primary, secondary or private health facilities to this tertiary health facility.

Type of study: This was a retrospective study in which hospital records of female patients who presented for management of infertility were retrieved by simple random sampling.

Inclusion criteria: Those included in the study were Black women, Nigerians by nationality, resident in the country and not visiting. Also included were those who had complete medical and gynecological records.

Exclusion criteria: Non-Nigerians, Caucasians, those on admission, those with fulminant neoplasm or with any severe illness were excluded.

Clinical examination and laboratory investigations: All patients were investigated appropriately. The attending gynecologists took relevant medical, gynecological and social histories from each patient. At the initial consultation and subsequently on each visit, each patient’s systolic and diastolic blood pressure was measured in a sitting position; fasting or random blood sugar or other appropriate investigation for the analysis of blood sugar was assessed. Where necessary, laparoscopy and appropriate gynecological procedures were conducted using standard methods in operation theatre or other designated places, especially for endometriosis. Evidence of endometriosis was based on the presence of chocolate ovarian cyst among other. Uterine fibroid was initially suspected based on palpation informative of enlarged irregular uterine configuration on examination of the pelvis after which a confirmatory diagnosing by Ultrasonography (USS) examination was made.

Ultrasonography was also used for the confirmation of other gynecological diseases. Venous blood was aseptically taken into appropriate containers and sent to the laboratory for investigations of hepatitis, HIV among other and for relevant endocrine profile of the patients. Data extracted from hospital records of the patients included their socio-demographic information, history medical and gynecological illnesses, and social history including consumption of alcohol, traditional medicinal herbal tea, cigarette smoking and use of tobacco. History of sexually transmitted diseases such as Gonorrhea, Human Immuno-deficient Virus (HIV) and Hepatitis were also extracted. Furthermore investigations that the patients had done and the results of such investigations, the diagnosis, prognosis and possible causative agents of their illnesses, these data were extracted by two trained research assistants into a pro-forma questionnaire designed by two of the three authors (JA, BMA) and verified by the third author (JAO). The data extraction was supervised and verified by one of the authors (JAO). Age was categorized into <26 years, 26-35 years, 36-45 years and >45 years. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as body weight in kilograms (kg) by height (squared) in meters or Kg/m2 before BMI was stratified as <18.5 (underweight), 18.5-24.9 (normal), 25.0-29.9 (overweight) and ≥30 (obese). The extracted data were then transferred into Excel spreadsheet, verified, cleaned and imported into statistical software for analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using NCSS 2021 (Kaysville, Utah, USA). Age (years) was categorized as ≤25, 26-35, 36-45 and >45, BMI (Kg/m2) was segregated into <18.5, 18.5-24.9, 25.0-29.9 and ≥30.24 Infertility was stratified as primary and secondary. The chi-square was used to test the significance of differences between two proportions while Pearson’s χ² was used to test the significance between more than two proportions in a pooled analysis. T-test was used to evaluate significant differences in means between two groups while one-way ANOVA were used to compare more than two samples. Relative risk, odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) as well as Correlation and Linear Regression Analysis were determined using appropriate commands. Data were presented as number (percent) or mean ± SD, Tables and Figures. P-value≤0.05 was considered significant.

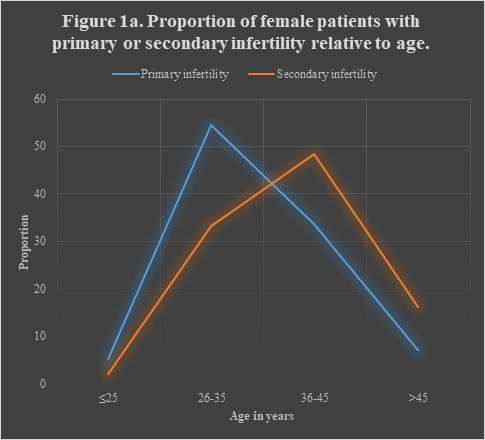

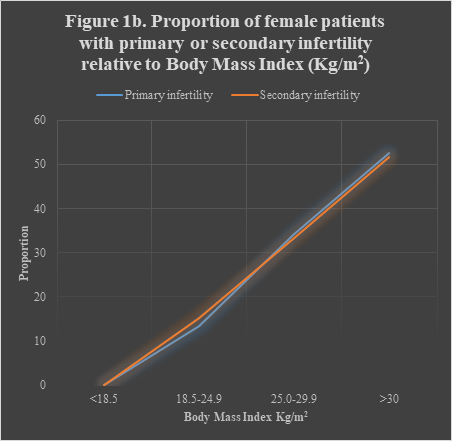

Frequency distribution of and relationship between age (years), Body Mass Index (Kg/m2) and types of infertility (Table 1, Figures 1a, 1b)

Variable |

Item |

n |

% |

Infertility |

χ² |

P-value |

Primary infertility |

Secondary infertility |

|||

Primary (n=158, 62.9%) |

Secondary (n=93, 37.1%) |

COR |

95% CI |

COR |

95% CI |

||||||

Age (years) |

≤25 |

10 |

4 |

8 (5.1) |

2 (2.1) |

0.65* |

0.42 |

2.43 |

0.50, 11.68 |

0.41 |

0.09, 1.98 |

26-35 |

117 |

46.6 |

86 (54.4) |

31 (33.3) |

10.47 |

0.001 |

2.39 |

1.40, 4.07 |

0.42 |

0.25, 0.71 |

|

36-45 |

98 |

39 |

53 (33.5) |

45 (48.4) |

5.42 |

0.02 |

0.54 |

0.32, 0.91 |

1.86 |

1.10, 3.14 |

|

>45 |

26 |

10.4 |

11 (7.0) |

15 (16.1) |

5.3 |

0.02 |

0.39 |

0.17, 0.89 |

2.57 |

1.13, 5.86 |

|

Mean (±sd) |

34.5 (6.6) |

37.7 (7.3) |

t-test = -3.59 |

0.0004 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|||

Pearson’s Chi-square=14.89, P-value=0.001 (H0 is rejected: Primary/Secondary Infertility and Age are associated) |

|||||||||||

BMI (Kg/m2) |

<18.5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

18.5-24.9 |

35 |

13.9 |

21 (13.3) |

14 (15.1) |

0.15 |

0.7 |

0.86 |

0.42, 1.80 |

1.16 |

0.56, 2.40 |

|

25.0-29.9 |

85 |

33.9 |

54 (34.2) |

31 (33.3) |

0.02 |

0.89 |

1.03 |

0.60, 1.79 |

0.96 |

0.56, 1.66 |

|

≥30 |

131 |

52.2 |

83 (52.5) |

48 (51.6) |

0.02 |

0.89 |

1.04 |

0.62, 1.73 |

0.96 |

0.58, 1.61 |

|

Pearson’s Chi-square=0.15, P-value=0.93 (H0 is not rejected: Primary/Secondary Infertility and BMI are not associated) |

|||||||||||

Table 1 Frequency distribution of and relationship between age (years), Body Mass Index (Kg/m2) and types of infertility among study subjects

*Fisher’s Exact Test; COR, crude odds ratio; No patient was underweight with BMI<18.5 Kg/m2.

Those aged 26-35 (117, 46.6%) and those with BMI≥30 Kg/m2 (131, 52.2%) formed the bulk of the study population. There was no study subject with BMI <18.5 Kg/m2. In all, the proportion of those with primary infertility (PI) (158, 62.9%) was higher than that of those with secondary infertility (SI) (93, 37.1%). Pearson’s chi square analysis shows that PI or SI was significantly associated with age (Pearson’s χ²=14.89, P-value=0.001) but not with BMI (Pearson’s χ²=0.15, P-value=0.93). This assertion is illustrated in Figure 1a which elaborates the proportion of study subjects with primary or secondary infertility relative to their age and in Figure 1b which shows the same proportion relative to their BMI. Women in age-group of 26-35 years were approximately 2½ times more likely to present with PI (χ²=10.47, P-value=0.001, COR=2.39, 95% CI= 1.40, 4.07) while those aged >45 years were roughly 2½ times more likely to present with SI (χ²=5.30, P-value=0.02, COR=2.57, 95% CI= 1.13, 5.86). (Table 1)

Figure 1a Pearson’s Chi-square=14.89, P-value=0.001 (H0 is rejected: Primary/Secondary Infertility and Age are associated).

Figure 1b Pearson’s Chi-square=0.15, P-value=0.93 (H0 is not rejected: Primary/Secondary Infertility and BMI are not associated).

Frequency distribution and risks of chronic illnesses, infectious diseases and other gynecological diseases relative to type of infertility among study subjects (Table 2)

|

Variable |

Item |

All Freq.(%) |

Type of infertility |

χ² |

P-value |

Primary infertility |

Secondary infertility |

|||

|

Primary (n=158) |

Secondary (n=93) |

RR |

95%CI |

RR |

95%CI |

|||||

|

Chronic illness |

Hypertension |

24 (9.6) |

14 (8.9) |

10 (10.8) |

0.24 |

0.62 |

0.82 |

0.38, 1.78 |

1.21 |

0.56, 2.62 |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

17 (6.8) |

13 (8.2) |

4 (4.3) |

0.87 |

0.35 |

1.91 |

0.64, 5.70 |

0.52 |

0.18, 1.56 |

|

|

Cancer |

2 (0.8) |

1 (0.6) |

1 (1.1) |

0 |

1 |

0.59 |

0.04, 9.23 |

1.64 |

0.10, 26.50 |

|

|

Asthma |

1 (0.4) |

1 (0.6) |

0 (0.0) |

0 |

1 |

undefined |

undefined |

|||

|

Infectious disease |

Gonorrhea |

3 (1.2) |

1 (0.6) |

2 (2.2) |

0.22 |

0.64 |

0.29 |

0.03, 3.20 |

3.4 |

0.31, 36.96 |

|

HIV |

9 (3.6) |

7 (4.4) |

2 (2.2) |

0.34 |

0.56 |

2.06 |

0.43, 9.71 |

0.49 |

0.10, 2.29 |

|

|

Hepatitis B |

48 (19.1) |

22 (13.9) |

26 (28.0) |

7.45 |

0.006 |

0.5 |

0.30, 0.83 |

2.01 |

1.21, 3.33 |

|

|

PID |

1 (0.4) |

1 (0.6) |

0 (0.0) |

0 |

1 |

undefined |

undefined |

|||

|

Other gynecological diseases |

Uterine fibroid |

82 (32.7) |

41 (26.0) |

41 (44.1) |

8.75 |

0.003 |

0.59 |

0.42, 0.83 |

1.7 |

1.20, 2.41 |

|

Ovarian tumor |

8 (3.2) |

6 (3.8) |

2 (2.2) |

0.12 |

0.73 |

1.77 |

0.36, 8.57 |

0.57 |

0.12, 2.75 |

|

|

Endometriosis |

28 (11.2) |

18 (11.4) |

10 (10.8) |

0.02 |

0.88 |

1.06 |

0.51, 2.20 |

0.94 |

0.46, 1.96 |

|

|

PCOS |

24 (9.6) |

16 (10.1) |

8 (8.6) |

0.16 |

0.69 |

1.18 |

0.52, 2.64 |

0.85 |

0.38, 1.91 |

|

|

Adenomyosis |

9 (3.6) |

3 (1.9) |

6 (6.5) |

2.32 |

0.13 |

0.29 |

0.08, 1.15 |

3.4 |

0.87, 13.27 |

|

|

IUA |

12 (4.8) |

7 (4.4) |

5 (5.4) |

0.001 |

0.97 |

0.82 |

0.27, 2.52 |

1.21 |

0.40, 3.71 |

|

|

Polyps |

13 (5.2) |

8 (5.1) |

5 (5.4) |

0 |

1 |

0.94 |

0.32, 2.79 |

1.06 |

0.36, 3.15 |

|

Table 2 Frequency distribution and risks of chronic illnesses, infectious diseases and other gynecological diseases relative to type of infertility among study

In all, hypertension (HT) was the most prevalent chronic illness among the study subjects (24, 9.6%) followed by diabetes mellitus (DM) (17, 6.8%). Hypertension was more prevalent (10/93, 10.8%) and had higher relative risk (χ²=0.24, P-value=0.62, RR=1.21, 95% CI=0.56, 2.62) among those with SI than among those with PI (14/158, 8.9%), while DM was more prevalent (13/158, 8.2%) and had higher relative risk (χ²=0.87, P-value=0.35, RR=1.91, 95% CI=0.64, 5.70) among those with PI than those with SI (4/93, 4.3%). Hepatitis was the commonest infectious disease (48/251, 19.1%) with a higher relative risk among those with SI (χ²=7.45, P-value=0.006, RR=2.01, 95% CI=1.21, 3.33) compared to those with PI (22/158, 13.9%). However, the prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) (9/251, 3.6%) was more common in PI than in SI subjects. In all, uterine fibroid (82/251, 32.7%) ranked highest as a co-morbidity with infertility, and most prevalent in SI (41/93, 44.1%) than in PI (41/158, 26.0%). The overall individual prevalence of other gynecological diseases as co-morbidity with infertility were endometriosis (28/251, 11.2%), Endometriosis (28/251, 11.2%), Polycystic ovarian syndrome (24/251, 9.6%), Uterine polyps (13/251, 5.2%), Intrauterine adhesion (12/251, 4.8%), Adenomyosis (9/251, 3.6%), and Ovarian tumor (8/251, 3.2%). Of these, those with SI had a higher relative risk of adenomyosis (χ²=2.32, P-value=0.13, RR=3.40, 95% CI=0.87, 13.27) while those with PI had a higher relative risk of ovarian tumor (χ²=0.12, P-value=0.73, RR=1.77, 95% CI=0.36, 8.57). (Table 2)

Prevalence of different diseases among women with primary or secondary infertility relative to age group (years) (Table 3)

|

Variable |

Item |

Type of infertility |

Pearson’s χ² |

df |

P-value |

||||||||

|

Primary (n=158) |

Secondary (n=93) |

||||||||||||

|

Age (years) |

|||||||||||||

|

<25 (n=8) |

26-35 (n=86) |

36-45 (n=53) |

>45 (n=10) |

<25 (n=2) |

26-35 (n=31) |

36-45 (n=45) |

>45 (n=15) |

||||||

|

Chronic illness |

Hypertension |

1 (12.5) |

4 (4.6) |

4 (7.5) |

5 (50.0) |

0 (0.0) |

4 (12.9) |

6 (13.3) |

0 (0.0) |

5.9 |

3 |

0.12 |

|

|

Diabetes mellitus |

0 (0.0) |

6 (7.0) |

6 (11.3) |

1 (10.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (3.2) |

2 (4.4) |

1 (6.7) |

1.12 |

2 |

0.57 |

||

|

Cancer |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (1.9) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (3.2) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

2 |

1 |

0.16 |

||

|

Asthma |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (1.9) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

- |

- |

- |

||

|

Infectious disease |

Gonorrhea |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (1.9) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (3.2) |

1 (2.2) |

0 (0.0) |

0.75 |

1 |

0.39 |

|

|

HIV |

1 (12.5) |

4 (4.6) |

2 (3.8) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

2 (6.4) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1.29 |

2 |

0.53 |

||

|

Hepatitis |

2 (25.0) |

10 (11.6) |

9 (17.0) |

1 (9.1) |

0 (0.0) |

8 (25.8) |

14 (31.1) |

4 (26.7) |

4.81 |

3 |

0.13 |

||

|

PID |

0 (0.0) |

1 (1.2) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

- |

- |

- |

||

|

Other gynecological diseases |

Fibroid |

0 (0.0) |

17 (19.8) |

20 (37.4) |

4 (36.4) |

0 (0.0) |

13 (41.9) |

22 (48.9) |

6 (40.0) |

1.03 |

2 |

0.6 |

|

|

Ovarian tumor |

1 (12.5) |

3 (3.5) |

1 (1.9) |

1 (9.1) |

1 (50.0) |

1 (3.2) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1.33 |

3 |

0.72 |

||

|

Endometriosis |

0 (0.0) |

12 (13.9) |

5 (9.4) |

1 (9.1) |

1 (50.0) |

2 (6.4) |

4 (8.9) |

3 (20.0) |

7.59 |

3 |

0.05 |

||

|

PCOS |

6 (75.0) |

8 (9.3) |

2 (3.8) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (50.0) |

1 (3.2) |

4 (8.9) |

2 (13.3) |

10.14 |

3 |

0.02 |

||

|

Adenomyosis |

0 (0.0) |

2 (2.3) |

1 (1.9) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (3.2) |

4 (8.9) |

1 (6.7) |

2.4 |

2 |

0.3 |

||

|

IUA |

1 (12.5) |

5 (5.8) |

1 (1.9) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (3.2) |

1 (2.2) |

3 (20.0) |

6.51 |

3 |

0.09 |

||

|

Polyps |

0 (0.0) |

6 (7.0) |

2 (3.8) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

3 (9.7) |

2 (4.4) |

0 (0.0) |

0.32 |

1 |

0.57 |

||

Table 3 Prevalence of different diseases among women with primary or secondary infertility relative to age groups (years)

Pooled analysis shows no significant difference in the distribution of any of the chronic illnesses or infectious diseases by age distribution in PI or SI, though there were marginally significant divergence in the spread of endometriosis (Pearson’s χ² = 7.59, P-value = 0.05) and momentous variation in PCOS (Pearson’s χ² =10.14, P-value = 0.02). Hypertension (5/10, 50.0%) and DM (6/33, 11.3%) were observed more in PI aged >45 and 36-45 years respectively. Hepatitis was most prevalent in SI aged 36-45 years (14/45, 31.1%) and in PI aged <25 years (2/8, 25.0%) while uterine fibroid was more commoner in SI aged >45 years (6/15, 40.0%) and in PI aged 35-45 years (20/53, 37.4%).

Prevalence of different diseases among women with primary or secondary infertility relative to body mass index of study subjects (Table 4)

There was also no significant difference in the spread of chronic illnesses, infectious diseases and other gynecological diseases relative to BMI and type of infertility. However, it is pertinent to observe that HT was more prevalent in obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) women with SI (10/48, 20.8%) than those with PI (9/83, 10.8%) while DM was more common in obese women with PI (6/83, 7.2%) than in obese women with SI (3/48, 6.2%). The highest prevalence of hepatitis (6/14, 42.9%) was observed in normal weight women with SI. Among those with PI, hepatitis was more common (4/21, 19.0%) in those with normal weight (Table 4).

Distribution of different diseases among women with primary infertility in different age groups relative to body mass index of study subjects (Table 5)

Among all those with PI in all categories of BMI, none in age group of ≤25 years presented a chronic disease. The only exception was among overweight women among whom one subject (1/5, 20%) presented with hypertension. Among those with PI, the highest prevalence of HT (4/7, 57.1%) was observed in obese women aged >45 years, of DM (2/12, 16.7%) was observed among overweight women, of hepatitis (3/8, 37.5%) was observed among normal weight women. Endometriosis was commoner (3/11, 27.3%) in normal weight women aged 26-35 years. In a pooled analysis, there was a noticeable difference (Pearson’s χ²=9.80, P-value=0.04) in the distribution of IUA relative to BMI and age.

Distribution of different diseases among women with secondary infertility in different age groups relative to body mass index of study subjects (Table 6)

Among those with SI, HT was most prevalent (4/13, 30.8%) in obese women aged 26-35 years, DM in overweight women aged >45 years (1/5, 20.0%), hepatitis in normal weight women aged 36-45 years (2/4, 50.0%) and aged >45 years (2/4, 50.0%). The most prevalent gynecological co-morbidity was uterine fibroid, observed in obese women in the age-group of 36-45 years (17/29, 58.6%).

Correlation and Linear regression analysis of infertility (primary and secondary as dependent variables) against various other conditions as independent variables (Figures 2a-2j)

Figures 2a-j show significant correlations between infertility and hepatitis (r=0.17, P-value=0.006, 95% CI= 0.06, 0.36) and between infertility and fibroid (r=0.1868, P-value=0.003, 95% CI=0.07, 0.32). No other variable showed any significant correlation with infertility though adenomyosis approached a level of marginal significance (r=0.12, P-value=0.06, 95% CI= -0.01, 0.62).

This retrospective study used data of women in child-bearing age group attending weekly clinic at a tertiary hospital in south of Nigeria between 2018 and 2019 to investigate the most prevalent type of female infertility and assess chronic medical, infectious and other gynecological illnesses that could exist as co-morbidity with either form of infertility. This approach is very relevant since social, environmental and other factors can elicit health conditions that may trigger or be linked with primary or secondary infertility. At any rate, at the clinic, gynecologists, physicians or fertility experts should be able to identify any co-morbidity with female infertility and provide satisfactory management of not only infertility but also co-morbidity. There are some key findings in the study that warrant further discussion. First and foremost, before going through co-morbidity factors, the issues of age and BMI come to the forefront. Age is a definitive factor that has been known to predispose a woman in reproductive age to a higher risk of infertility in that the quality and also quantity of a woman’s eggs gradually reduce with age such that by about 35 years of age, speed of follicle loss is faster, leading to possibility of fewer and poorer eggs, difficulty in conceiving and higher risk of miscarriage. In this facility-based study, prevalence of female primary infertility was 62.9%, a figure that is higher than the 51.4% reported by Maheshwari et al.,25 but lesser than the 68.9% reported from Khartoum, Sudan26 or the 78.0% reported from Henan Province in China.27

This might be due to modern Nigerian women in reproductive age wanting to have an income, be independent of men or want to establish a corporate identity in various industries in which early pregnancy may deny them the opportunity of self-establishment. Another possible reason is that men are not ready to get married because of unemployment and scarce income to support a family. Studies have actually reported that more men in the country are having fewer or no sperm cells.28,29 The 46.6% prevalence of primary infertility in the age group of 26-35 years is similar to the 46.0% reported in the same age group from an Indian study30 but the 48.4% prevalence of secondary infertility among those aged 36-45 years in this study in this much higher than the 21.6% reported in the same Indian study.

The submission of Cates et al.,31 that African couples were more likely, than those from elsewhere, to have secondary infertility or longer duration appears paradoxical, though it should still be considered in the context of a population-based and not facility-based study. Another key finding is that there was no significant difference in the effect of Body Mass Index in primary or secondary infertility. Many studies have reported the influence of BMI on infertility. For example Zhu et al predicted that the relationship between infertility and BMI presented a U-shaped curve and that underweight and obese BMI tended to predict infertility.32 In this study, the proportion of women that were obese (52.2%) or overweight (33.9%) was higher than the respective 46.4% or 39.4% reported from a study in Algeria.33

However, there was no significant difference of the effect of BMI on primary and secondary infertility, though further studies on factors not considered in this study, such as insulin-sensitizing adipokines and abundance of adipose tissues34 may demonstrate potential effects of BMI on the two types of infertility. Stratification by BMI showed that hypertension was most prominent in obese women, regardless of the type of infertility while diabetes was most prominent in normal weight women with primary infertility as well as in obese women with secondary infertility. Although there was no significant difference in the proportion of women with primary or secondary infertility who presented with hypertension or diabetes, still overall, hypertension was more prevalent in those with secondary infertility, with a slightly higher risk, while diabetes was seen more in those with primary infertility, with about twice the risk compared to secondary infertility. However when stratified by age, women with primary infertility, aged over 45 years, were most likely to present with hypertension. The insignificantly higher prevalence of hypertension in secondary infertility may be due to the normal degenerative process as those with secondary infertility were significantly older than those with primary infertility.

Lack of regular exercise, increased sodium salt intake and obesity may also be responsible as risk factors for the hypertension found in both primary and secondary infertility. Plasma leptin concentration35 may be raised in women with secondary more than those with primary infertility, though this needs further study. Ghafarzadeh et al had linked infertility in women with the development of metabolic syndrome such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, insulin resistance, and obesity and various cardiovascular abnormalities.36 in obesity-associated diabetes, cytokines released from adipocytes; adipokines - especially adiponectin - probably play significant roles in reciprocally modulating levels of glucose and insulin, among other things.37 Further, lowered concentration of high molecular adiponectin has been found to be linked with cardiovascular disorder in type II diabetic patients.38

This calls for further studies on adiponectin among infertile Black African women in sub-Saharan Africa that present with primary or secondary infertility and with overweight or obesity, hypertension and/or diabetes. A major key finding in this paper is the high prevalence of Hepatitis B, more in those with secondary, with twice the relative risk, compared to those with primary infertility. The overall 19.1% prevalence of HBV in this study was higher than the 2.9%, 3.9% and 6.9% reported among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Uganda,39 northern part of Nigeria40 and in Ethiopia41 respectively. Possibly, HBV is a cause of idiopathic infertility, an issue that should be explored further in infertility clinics in Africa. Another report observes that individuals with HBV are 1.59 times more likely to experience infertility than individuals who are not infected.42 the overall number of women with Gonorrhea, HIV and PID were too few to make a meaningful deduction, though the relative risk of gonorrhea was about 3½ higher in secondary than in primary infertility. Finally, the 9.6% prevalence of PCOS reported in this study is lower than the 13.8% reported from the Benin City in South-south Nigeria,43 the 18.1% documented in Enugu, South-east Nigeria44 and 33.0% reported in Iraq45 respectively.

Limitations

There are few limitations in this study that need consideration, the first of which is the sampling size which may be insufficient to generalize to the Nigerian population and the sampling method which may introduce bias. Also, the study was conducted in the tropical forest region of the south and may not reflect the true picture in the arid Savannah region of the north. Further, this was a retrospective study and, though very remote, there might have been some error in data records, a phenomenon that is common to most retrospective studies.

In the analysis of this study, the proportion of women in the reproductive age who presented with primary infertility was higher than those who presented with secondary infertility. The study also observed that, confirming what has been reported, age and infertility are associated with both primary and secondary infertility whereas Body Mass Index has the same association with either primary or secondary infertility. Hypertension and Diabetes were almost equally distributed in both types of infertility though the risk of hypertension was higher in women with secondary than in those with primary infertility. Conversely, the risk of diabetes was higher in women with primary than in those with secondary infertility. The most prominent infectious disease was Hepatitis B virus (HBV) which was more prominent in those with secondary than in primary infertility. The study also found that uterine fibroid was the most common co-morbidity, especially in those with secondary infertility. Endometriosis, Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), Intrauterine adhesion and polyps also featured prominently as co-morbidity, the former two in primary and the latter two in secondary infertility. Significant correlation was observed between infertility and hepatitis. Screening for hepatitis should be incorporated and aggressively pursued as one of the run-ups for female infertility examination in sub-Saharan Africa. Further, a nationwide, population-based survey of hepatitis in Nigeria should be undertaken and reviewed on four-year basis.

None.

The authors declared no potential conflict of interest.

None.

©2022 Olamijulo, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.