International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9889

Research Article Volume 4 Issue 5

1Department of Nursing, college of health science, Debre Tabor University, Ethiopia

2School of Nursing, college of health science, Jimma University, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Worku Necho, Departments of Nursing, Debre Tabor University, Debre Tabor Town, Ethiopia, Tel 251-918-487-752

Received: November 29, 2017 | Published: September 6, 2018

Citation: Asifere WN, Tessema M, Tebeje B. Clients’ satisfaction with health care providers’ communication and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Jimma town public health facilities, Jimma zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Int J Pregn & Chi Birth. 2018;4(5):223-230 DOI: 10.15406/ipcb.2018.04.00113

Background: Satisfactory client-provider communication is essential especially when providing antenatal care. Despite improved antenatal coverage, client-provider communication during antenatal care service is still poor. Even though, client-provider communication reduces challenges of pregnancy complications, it is mostly ignored in medical researchers. In Ethiopia, such studies are non-existent both at national and local level.

Objective: To assess clients’ satisfaction with health care providers’ communication and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Jimma Town public Health Facilities, Jimma Zone, and Southwest Ethiopia.

Methodology: Cross sectional study design with mixed data collection method was conducted, from March 1 to 30/2017. Three hundred twenty two clients and six key informants participated in this study. Participants selected using systematic random sampling technique. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected from clients and key informants using structured questionnaires and in-depth interview guide respectively. Data were entered into Epi data and exported into SPSS version 21.0 for analysis. Descriptive statistics, bivariate and multivariate binary logistic analyses were carried out. Qualitative data were analyzed based on thematic frameworks to triangulate quantitative findings.

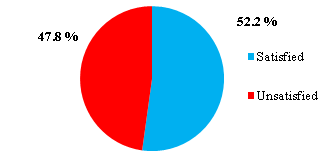

Result: Overall status of clients’ satisfaction with providers’ communication accounted 163(52.2%). Highest satisfaction (70.8%) was reported on providers’ support and respect dimension. similarly, 54.7% and 43.5% of clients were dissatisfied with providers’ information provision and clients’ consultation time dimension respectively. According to multivariate analysis clients’ marital, educational and occupational statuses were predictors of communication satisfaction. Qualitative finding reveals shorter consultation time, inappropriate utilization of aids and low health information were major reported challenges.

Conclusion and recommendation: status of clients’ communication satisfaction was low compared to other studies. Clients’ occupation, educational and marital status were significant predictors of communication satisfaction. Investigator recommends providers should give relevant health message to pregnant women with appropriate communication.

Keywords: providers communication, clients’ satisfaction, antenatal care

ANC; antenatal care, CSA; central statistics agency, EDHS; ethiopian demographic health survey, ETB; ethiopian birr, FANC; focused antenatal care, HCPs; health care providers, HIV/AIDS; human immune virus and acquired immune deficiency syndrome, IEC; information, education and communication, MDG; millennium development goal, MHNCP; maternal health care provider, MMR; maternal mortality ratio, SDGs; sustainable development goals, SNNRP; south nation nationality regional people, UNICEF; united nations’ children education fund, WHO; world health organization

Antenatal care (ANC) involves careful, systematic assessment and follow-up of pregnant women, including education, counseling, screening, and treatments to improve pregnancy outcomes.1 It provides health information for recognizing pregnancy danger signs, childbirth, infant care, births spacing, breast feeding, and appropriate actions to be taken.2,3

Communication is defined as a multi-dimensional, multi-factorial phenomenon and complex process, closely related to environments in which an individual’s experiences are shared.4 It is also a dynamic two way verbal and non-verbal information exchange from diagnosis to treatment plan in medical services.3 Satisfaction- defined as the extent of an individual’s experience compared with his or her expectations. Client’s satisfaction is one of commonly used outcome measures of patient care and an important indicator of quality of healthcare performance.5 Client’s satisfaction with ANC is clinically relevant, as satisfied women more likely abide with treatment, take an active role in their own care, continue using the services and stay with health care providers. It is considered as an important indicator of efficient utilization of health services, because it assesses the extent to which the service meets person’s requirements and needs.6 Emotional support, communication of concerns and understanding by health staffs are crucial in providing quality and satisfactory services in clinical care. Information, education and communication (IEC) by health care provider to pregnant woman during antenatal visits are indispensable for healthy pregnancy outcomes.3

Globally, an estimated of 303,000 women died yearly due to pregnancy complications and child birth. Even if, annual number of maternal deaths fell by 44% between 1990 and 2015, from approximately 385 to 216 deaths per 100,000 live births which is still very high. In developing countries, MMR is almost 20 times higher than developed countries which accounts approximately 99% of global maternal deaths, with sub-Saharan Africa alone accounts 66%.7,8 Maternal mortality is one of serious health problems in Ethiopia. According to EDHS 2011 and 2016, MMR was 676 and 412 deaths per 100,000 live births respectively which are strikingly high.9,10 Different interventions are designed and applied to alleviate problems of maternal morbidity and mortality. Focused Antenatal care service (FANC) is one of the Key interventions to improve maternal health and reduce maternal death. Extensive efforts have been made to improve reproductive health services and to reduce maternal and child mortality. A lot of initiatives were also applied to encourage ANC utilization, including intensive information, education and communication on maternal health services offered in all health facilities.7 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set a goal for global MMR to be below 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births with an average of 7.5% each year between 2016 and 2030. Ethiopia also takes commitment of SDGs to achieve this goal. The FANC needs effective HCPs communication with pregnant women during ANC service provision to be more productive.8

Health facility related factors including unavailability of appropriate drugs and skilled health workers, poor attitude and poor professional conduct (failure to respect privacy and confidentiality of clients) accounted for 27.5% of pregnant women not to attend ANC services. Poor client-provider communications and unfriendly behaviors of providers are major factors which inhibit women’s service utilization and satisfaction.11 Despite improved antenatal coverage, there is still poor client- provider communication during antenatal care services which hinder exchange of information and negatively affect client’s trust on providers.12 Lack of respectful care from health care providers diminishes utilization of ANC, delivery and postnatal services. In addition, it affects the well-being of pregnant women and their relationship with providers.13 Information exchange, responding to emotions, managing uncertainty, and fostering trusting relationships are critical features of successful interpersonal communication between clients and providers. Effective communication is an important for clients to feel their concerns heard and creates mutual understanding between clients and provider regarding client’s life situation which increase client’s satisfaction.12 Even though, client-provider communication reduces challenges which occur due to pregnancy related complications, it is mostly ignored in medical researchers.14 In Ethiopia, similar studies are non-existent at national in general and in Jimma Town in particular. Therefore; this study aims to identify clients’ satisfaction with health care providers’ communication and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Jimma Town Public Health Facilities.

Clients satisfied with quality of ANC service and provider communication had a great intention to attend services for the future.12,15 There was no study conducted on factors that affect clients’ satisfaction with health care providers’ communication during ANC in our local context. So, this study will give an insight on clients’ satisfaction with health care providers’ communication and associated factors in Jimma Town Public Health Facilities. It helps health care providers to identify communication factors and initiate interventions based on a research finding. It will also help to improve health care providers’ and women’s communication during ANC service provision. It also gives a guide for policy makers and stakeholders with updated information for future planning and interventions. Finally, it will be used as a baseline for scientific community to conduct extensive study in this area.

General objective

To assess status of clients’ satisfaction with health care providers’ communication and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Jimma Town Public Health Facilities, Jimma Zone, Southwest Ethiopia, 2017

Specific objectivesThe study was conducted in Jimma Town Public Health Facilities. Jimma Town is located in Jimma Zone, Oromo Regional State, and Southwest Ethiopia. It is the capital city of Jimma Zone which is located 354 km from Addis Ababa; the capital city of Ethiopia. The Town has thirteen kebele with a total population of 120,960 of whom females account 60, 136.16 It has six public health facilities including, two public hospitals and four health centers. All health centers and Hospitals had a total of 132 and 966 health professionals respectively. All Health Facilities provide ANC service in-addition to others services. The study was conducted from March 1- 30/2017.

Study designFacility based cross-sectional study design using quantitative and qualitative data collection methods was employed.

Source populationAll pregnant women attending antenatal care during data collection period in Jimma Town Public Health Facilities.

Key Informants from health care providers working in ANC clinic in Jimma Town Public Health Facilities.

Study populationSampled pregnant women attending antenatal care service in Jimma Town Public Health Facilities during data collection period.

For qualitative approach, a minimum of six key informants from health care providers who were assigned at ANC clinic at Jimma Town Public Health Facilities were selected.

Sample size determinationSample size for quantitative approach was determined using single population proportion formula , where n is sample size, Z the standard normal deviation, set at 1.96 (for 95% confidence interval), D is the margin of error(0.05 was taken), P is estimated prevalence of clients’ communication satisfaction (50%). Correction formula was also used to calculate final sample size and considering 10% non-response rate the total sample was 322. For qualitative approach, six key informants were selected for in-depth interview.

Sampling proceduresAll health facilities were included in the study. Study participants were identified using systematic random sampling technique among pregnant women attending ANC during study period.17,18 The calculated sample size was proportionally allocated to each Facility based on average number of pregnant women attending ANC for one month during the most recent quarter report (170 for H2 H/C, 231 for Jimma H/C, 104 for B/Bore H/C, 130 for M/Kochie H/C, 351 for JUSH and 241 for Shenengibe Hospital).19 The interval used to select pregnant women for data collection was determined by constant number (K=4) which was a total number of source population divide by number of sample size i.e. K=1227/322=4. The total numbers of cards seen daily at each facility were used as a framework. The first participant was picked out by lottery method and others interviewed every four interval. For qualitative approach, purposive sampling technique used to select one key informant from each facility for an in-depth interview (criteria for selection of key informants was their position and work experience in ANC clinic to get rich information).

Data collection methodsSix diploma nurses for data collection and three BSC nurses for supervision were recruited. Quantitative data was collected using a structured and pretested questionnaire adapted after review different literatures.17,20–22 The questionnaire was first developed in English and translated into Afan Oromo and Amharic versions and re-translated back into English by language experts to assure its consistency. Participants were interviewed in appropriate place by trained data collectors after using the services and immediately before exit from health facilities compound. For qualitative data, in-depth interview was conducted with selected key informants using guide and tape recorder after appropriate time selection. Before conducting discussion, explanation and elaboration of the need for interview was explained to them. Each in-depth interview took 1½ to 2 hours. The qualitative data were used for triangulating quantitative data.

Data collection tools

To assess clients’ satisfaction with health care providers’ communication four exposure items were employed which includes socio-demographic measuring items, Communication satisfaction measuring Likert scale items, clients’ knowledge measuring items, and in-depth interview guide items for qualitative data were used.

Data quality control

Training was given for data collectors and supervisors by principal investigator. The questionnaire was pre-test on 5% (16 clients) of study participants in Serbo health center, who were not involved in actual data collection and modification was done accordingly. During data collection, trained supervisors strictly supervised the correctness of the questionnaire. Principal investigator also checked the completeness and correctness of filled questionnaires.

Data were entered using Epi data version 3.1. The internal consistency of Likert scale items were assessed using Cronbach’s alpha which was within acceptable range > 0.7. Item loading was conducted for factors constituting each dimension of Likert scale items. Accordingly, providers’ communication skill factors were explained 59.7 %, Provider Health information provision factors 62.6 %, Consultation time factors 54.6 %, Provider’s support and respect factors 57.5 % of satisfaction variance among pregnant women attending ANC at study area.

Data analysisEach questionnaire was checked for completeness, missed values and unlikely responses. The collected data were entered into a computer using Epi-data version 3.1. The data were cleaned and exported to SPSS software version 21(IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) for analysis. Descriptive, bivariate and multivariate logistic analyses were carried out Odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI was used to examine the associations between dependent and independent variables. All variables were entered into bivariate analysis and those variables with a p value <0.25 in crude analysis were taken as a candidate for multivariate analysis. For multivariate analysis, binary logistic regression was carried out, and statically significance was considered when p value <0.05. Hosmer and Leme show goodness-of-fit statistic (chi-square 9.895, P-value 0.272) was done with p-value >0.05 approved the model was good. For qualitative survey, data were first transcribed into text format and translated into English version. Then, data analyzed manually using thematic analysis technique. Initially, data were read several times to identify major themes. After Coding, data’s were compared and organized into themes. Finally, quantitative results were presented in texts, tables and graphs as appropriate and qualitative results were used to triangulate the quantitative results.

Ethical clearance was obtained from Jimma University Institutes of health Ethical Review Board. Official letter was written to Jimma Town Health Office. Participants’ confidentiality and anonymity was kept. Informed verbal and written consent were also taken individually, and any respondents who were not assured given a full right to refuse to participate in the study without any negative connotation on their future service.

Socio-demographic distributions’ of respondents

Out of 322 eligible clients, 312 enrolled into the study yielding response rate of 96.9%.The largest number of pregnant women belongs to the age range of 25-34 years 145(46.5%). The mean age of respondents was 25.4 year (SD+5.482). Out of 312 respondents, 171(54.8%) were housewives. Predominant ethnicities were Oromo 174(55.8 %) and Yem 30(9.6 %) while the dominant religion was Muslim149(47.8%). Further details were reported in (Table 1).

Socio-demographic distributions |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

|

Age |

18-24 year |

142 |

45.5 |

25-34 year |

145 |

46.5 |

|

35 - 44 year |

25 |

8 |

|

Oromo |

174 |

55.8 |

|

Amhara |

36 |

11.5 |

|

Ethnicity |

Dawro |

33 |

10.6 |

Yem |

30 |

9.6 |

|

Kefa |

18 |

5.8 |

|

Gurage |

13 |

4.2 |

|

Others * |

8 |

2.6 |

|

Educational status |

Unable to read and write |

167 |

53.5 |

Primary school |

76 |

24.4 |

|

Secondary school |

27 |

8.7 |

|

College/University |

42 |

13.5 |

|

Orthodox |

82 |

26.3 |

|

Protestant |

67 |

21.5 |

|

Religion |

Muslim |

149 |

47.8 |

Catholic |

14 |

4.5 |

|

Others ** |

10 |

3.2 |

|

Single |

24 |

7.7 |

|

Marital status |

Married |

281 |

90.1 |

Divorced |

7 |

2.2 |

|

Governmental employee |

49 |

15.7 |

|

Non-governmental employee |

9 |

2.9 |

|

Occupation status |

Housewife |

171 |

54.8 |

Merchant |

39 |

12.5 |

|

Student |

8 |

2.6 |

|

Farmer |

19 |

6.1 |

|

Daily laborer |

17 |

5.4 |

|

Income |

< 1000 birr |

10 |

3.2 |

1000- 1500.00 birr |

64 |

20.5 |

|

1501-2000.00 birr |

63 |

20.2 |

|

|

2001 and above birr |

175 |

56.1 |

Table 1 Socio-demographic and economic distributions of pregnant women attending antenatal care at Jimma Town Health facilities, Jimma Zone, 2017

Note: *Tigray, Wolaita and silty ethnic group, **Adventists and Wahhabi religious group

Institutional and clients’ obstetric related factors

Majority of clients were attended first antenatal visit 121(38.9 %) followed by second visit 87 (27.9%). Nearly one third, 103(33.0%) of respondents reported their privacy were not maintained during physical examination. About 140(44.9 %) of clients had complaint on continuity of care with similarcare providers. Most of clients 135(43.3%) were stayed more than two hours until they access ANC.

Women’s knowledge on importance of antenatal care

In order to assess client’s knowledge on ANC, eight items were utilized. For interpretation, zero was given for those who didn’t give correct answer and one for correct answer. Then, total knowledge score was computed. Out of 312 clients, majority 235(75.3 %) of them had good knowledge regarding to importance of ANC (Figure 1).

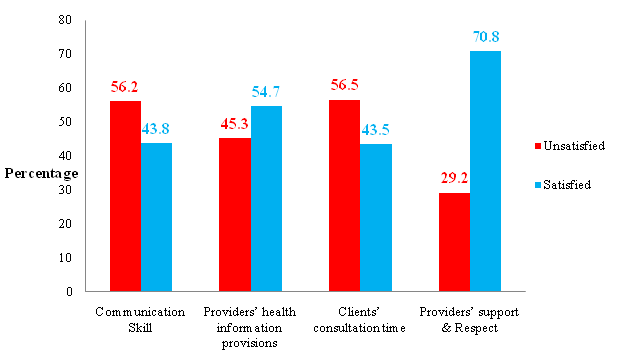

Figure 1 Level of Clients’ satisfaction with each communication satisfaction measuring Dimensions, Jimma Town Public Health facilities, 2017.

Areas of greatest dissatisfaction too clients

Majority of clients’ expressed the greatest dissatisfaction on continuity of care 140(44.9 %) by similar provider. Additionally, 156 (48.4 %) respondents were not satisfied with consultation time on antenatal checkup. Clients also had great dissatisfaction in waiting time 135(43.3%) and providers’ communication skill 142(44.1 %) during antenatal examination (Table 2).

Variables |

|

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

Parity |

Nulli Para |

81 |

26 |

01-Feb |

156 |

50 |

|

3 and above |

75 |

24 |

|

1st visit |

121 |

38.9 |

|

ANC Visit |

2nd visit |

87 |

27.9 |

3rd visit |

62 |

19.9 |

|

> 4th visit |

42 |

13.5 |

|

Yes |

172 |

55.1 |

|

Continuity of care |

No |

140 |

44.9 |

Yes |

209 |

67 |

|

Privacy |

No |

103 |

33 |

5-15 minute |

132 |

42.4 |

|

Clients Contact Time |

16-25 minute |

135 |

43.6 |

26-35 minute |

45 |

14.4 |

|

< 1 hours |

74 |

23.7 |

|

Waiting time |

1-2 hours |

103 |

33 |

|

> 2 hours |

135 |

43.3 |

Table 2 Institutional and clients obstetric related factors of pregnant women attending ANC in Jimma Town Public Health Facilities, 2017

Overall status of clients’ communication satisfaction

Among 312 clients, 163(52.2 %) were satisfied with providers’ communications during their antenatal care. Overall status of clients’ satisfaction with health care providers’ communication was assessed at each health facility. From this, 24(53.3 %) in H2 H/C, 29(47.5%) in Jimma H/C, 12 (44.4 %) in B/Bore H/C, 21(61.8 %) in M/Kochie H/C, 26(41.3 %) in Shenegibe Hospital and 58 (63.0 %) were satisfied with health care providers’ communication. In Hospitals, 94(60.6 %), 104(67.1%), 84(52.2 %) and 117(75.5 %) of clients were satisfied with provider communication skill, providers’ health information provision, provider’s consultation time, and provider’s respect and support respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Status of clients’ satisfaction with providers’ communication among pregnant women attending ANC at Jimma Town Public Health facilities, 2017.

Factors associated with clients’ Satisfaction with providers communication

The bivariate analysis revealed that clients’ ethnicity, occupational status, educational status, religion, marital status, family size and clients’ ANC visit were associated with clients’ communication satisfaction (Table 3). Multivariate analysis using binary logistic regression was made to identify predictors of clients’ communication satisfaction. All candidate variables were entered into final model to control confounders. Finally, variables with p<0.05 were taken as significant predictors of clients’ communication satisfaction. Clients’ marital, educational and Occupational statuses were significant predictors of their satisfaction with health care providers’ communication. For instance, respondents with single marital status were 82.9% times less likely to be satisfied with providers’ communication as compared to married women. In addition, clients completing secondary education and college or university were 4.207 and 2.75 times more likely to be satisfied compared to clients who can’t read and write respectively. Similarly, clients’ having merchants profession were also 66.3% times less likely to be satisfied with providers’ communication compared with housewives.

Variables |

Satisfied n (%) |

Unsatisfied n (%) |

COR(95% CI) |

AOR(95%CI) |

P. V <0.05 |

Marital status |

|||||

Single |

6(3.5) |

18(11.7) |

0.278(0.087, 0.892) |

0.171(0.045,0.656) |

0.01 |

Married |

154(94.7) |

127(85.4) |

1 |

1 |

|

Educational Status |

|||||

Unable to read & write |

71(38.8) |

96(53.1) |

1 |

1 |

|

Secondary School |

6(3.9) |

21(13.3) |

5.102(1.432,18.17) |

4.207(1.554,11.393) |

0.005 |

College/University |

12(9.7) |

30(22.1) |

2.642(1.200, 5.817) |

2.752(1.152, 6.575) |

0.023 |

Occupation Status |

|||||

Housewives |

93(47.8) |

78(43.7) |

1 |

1 |

|

Merchants |

14(8.0) |

25(16.5) |

0.438(0.186, 1.031) |

0.337(0.121,0.94) |

0.038 |

Table 3 Predictors of clients’ satisfaction status with health care providers’ communication among pregnant women attending ANC at Jimma Town Public Health Facilities, 2017

Note: 1; Reference group

Qualitative result

Six key informants, one key informant from each health facility, were interviewed using in-depth interview guide. Data were analyzed manually after reading several times. Three major themes were made that influence client-provider communication during antenatal care. The themes were clients contact time, utilizations of communication aids and perception on factors that influence client-provider communication.

Clients contact time

Most of key informants stated the presence of short client contact time during ANC at health facility. As key informants stated clients’ contact time were decreased due to variations of clients flow, absence of safe working environments, shortage of staff, work overload and staff non-commitment. As stated by 27 years old key informant:

“I am not taking enough time to give the service for women because in our health facility there is high client flow per day nearly 20 to 35 women are seen per day. Especially, in Sunday and Thursday there is high client flow and work overload at morning time. During these days I gave the service within short minutes with a little explanation of health messages. This may affect women’s satisfaction with our communication.....”

Another key informant also confirms this idea “Mostly I use around 10 to 15 minute to provide the service for pregnant women. I know this time is not enough to provide all recommended activities and services for them. I give more emphasize for major activities to provide explanation and advice to pregnant women ...” Additionally, 25 years old key informants stated “in our health facility there is shortage of staff to provide antenatal services. I am assigned alone at this unit and my colleagues are not volunteers to help me and give appropriate services for pregnant women. So, I am obligated to give antenatal care with short periods of time to deliver the services for all women coming to attend ANC ...”

Utilizations of communication aids

Participants/informants reported that each health facility has some communication aids at ANC clinic to facilitate antenatal counseling and health education during ANC service provision. But, some of health facilities had shortage of aiding materials in numbers and type. Most of key informants also reported that they didn’t properly utilize these materials for clarification and to summary health information. Key informants also raised some factors that influence utilization of aids including shortage of aiding material, work overload and staff negligence to use materials.

A 32 years old key informant stated “In our facility there are some visual aids in ANC unit which explains about breast feeding, HIV/ADIS, times of pregnancy checkup and diets for pregnancy. But, I didn’t use them to explain health information for women while I give health education and advice for pregnant women. Other aiding materials like leaflets and poster are not available in adequate numbers. Since there is high client flow it is also difficult to use aiding materials to facilitate antenatal communication .....”

A 27 years old key informant also said “we have some aiding materials in our health facility to give health information for pregnant women. Those are posters on time of pregnancy checkup, breast feeding and about pregnancy danger sign. Sometimes I use these materials for clarification while providing antenatal counseling and advice. I doubt that women may be satisfied or not by my health information provision and communication style …”

Perception on factors that influence client-provider communication

Most of key informants raised different factors which influence client-provider communication such as inappropriate working areas, staff non-commitment, variation of client flow, language barrier between clients and providers, absences of examination screen and inappropriate utilization of visual aids. For instances, one of the key informant said;

“There are a certain problems in our health facility that influence clients’ communication satisfaction like language differences between women and health care providers, absence of adequate working space, shortage of staff and absence of adequate visual aids. Despite, these problems I try to give services with clarification and sometime I invite my colleagues for explanation to women having different language what I speak. To solve these problems I try to give health message orally by myself….

Another key informant also stated “in our health facility there are some aiding materials explaining about breast feeding, nutrition for pregnancy and HIV/AIDS. Sometimes I use them to provide antenatal care. If many women come I give the service rapidly without detail explanation. This may decrease clients’ satisfaction with health education and ANC…..”

Appropriate health care providers communication is one of an important aspect of ANC as satisfied women continued using the visit and take active role for care. Clients’ marital, occupational and educational statuses were significant predictors of clients’ communication satisfaction during their antenatal care.

Our study found out that, overall clients’ communication satisfaction accounted 52.2% which is low compared to other similar studies. A study in Pakistan showed 79% clients’ satisfied on communication.14 This discrepancy might be due to difference of subjective natures of respondents, availability of safe working environments and sample size. But, this finding is higher as compared to study conducted in Ghana (35%).23This inconsistency could be due to utilization of different satisfaction measurements, demographic variations, and difference of pregnant expectation toward providers’ interaction. Additionally, study conducted in Ghana enrolls both pregnant and non-pregnant women coming for maternity care.

This finding also showed that pregnant women attending ANC at Hospitals were more satisfied in providers’ respect and support dimension 117(75.5 %) followed by provider’s health information provision dimension 104(67.1%) while at health centers clients were more satisfied by provider’s respect and support aspect 146(87.4%) followed with clients’ consultation time dimension 113(67.7%). This discrepancy might be due to presence of high client flow at Hospitals which decreases clients’ consultation time compared to health centers. Additionally, at Hospitals more experienced and trained health professionals might be assigned at ANC unit.

In our study, clients who had completed secondary and higher education were 4.21 and 2.75 times more likely to be satisfied with health providers’ communication than clients who can’t read and write respectively. It was believed that higher literacy status increase level of expectation in services which decrease clients’ satisfaction.27 But, in this study Positive relationship was observed between educational status and clients’ satisfaction (i.e. as educational status increase, clients’ satisfaction also increase). The discrepancy might be due to clients who complete secondary and higher education can easily understand what health care professionals communicate and had clear understand on importance of ANC. It is also known that communication is facilitated by similar social and educational background. This finding is consistent with studies conducted in Iran and Swede.24,25 Additionally, Single respondents were 82.9% time less likely satisfied as compared to married women. This discrepancy could be due to single respondents may be ashamed by their pregnancy or may not want their pregnancy. The finding also indicates merchants were 66.3% times less likely satisfied with providers’ communication compared with housewives. This might be due to that merchants expect to get the service immediately arriving to facility and they might disapproval with long waiting time and short client contact times.

Satisfactory communication is important for clients to feel they are understood and creates mutual understanding between clients and providers. This study showed that, 56.2% of clients were satisfied by providers’ communication skill during their antenatal care visit. This finding is in line with study in Nigeria which was 57.2% women were satisfied with providers’ communication skill.15 But, this finding is inconsistent with qualitative finding as one of key informant stated “we have some aiding materials in our health facility to facilitate communication skill while providing health information for pregnant women. But, I am not always utilizing those materials for clarification when I provide antenatal counseling and advice. I doubt that women may be dissatisfied by my health information provision and communication skill…”

Appropriate health information concerning pregnancy condition is important for woman and her baby for healthy outcomes. This study showed that 54.7 % clients were satisfied with providers’ health information provision aspect. The qualitative finding also supports this idea as one of the key informants stated, “On Sunday and Thursday there is high client flow and work overload at morning time during these days I gave the service with a little explanation of health messages. But, if the number of women is appropriate I give the recommended antenatal health information to pregnant women ...” This finding is in line with study conducted in Sodo Wolaita zone and Gambia.13,26

Our qualitative finding also indicates absence of safe working area, high clients flow, and staff non-commitments to use visual aids during antenatal care were major factors associated with clients’ satisfaction with providers’ communication. This finding is consistent with study conducted in Ghana and Nigeria.27 In addition, qualitative finding also revealed that occasionally language barrier between Health care provider and clients, and absences of aiding materials for providing ANC were factors which influence clients’ communication satisfaction. As stated by 27 year old key informant “There are a certain problems in our health facility which influence clients’ communication satisfaction during antenatal care like language differences, and absence of enough visual aids….” This finding is similar with study conducted in Iran and Oman.

Limitations of the study

Since it is cross-sectional study, it is difficult to claim causal relationship and gives only evidences of clients’ status of communication satisfaction within times of study period. There might be social desirability bias as the interview conducted at health facility.

Our study identified overall clients’ satisfaction with providers’ communication was low compared to previous studies. Clients’ marital, educational and occupational statuses were significant predictors of their communication satisfaction. Clients were more satisfied with provider’s support and respect aspects/dimensions than others dimensions. Satisfaction varied between hospitals and health centers. Meanwhile, clients attending antenatal care at hospitals were more satisfied with providers’ support and respect followed by providers’ health information provision dimension while clients’ attending at health centers were more satisfied with providers’ support and respect dimension followed by clients’ consultation time. This implies that interventions to fill the gaps (dimension/areas) of clients’ satisfaction should be institutions specific (hospitals Vs H/Cs). Researchers need to conducts further studies regarding to clients-provider communication with strong study design at low resource settings such as longitudinal studies.

Authors thank Jimma University and school of Nursing for their contribution, data collectors and study participants deserve acknowledgements too.

Authors report there was no any funding sources for this study.

WN: conceptualized, designed the study, collect, analyses and interpretation the data and also drafted the manuscript. BT: designed the study; analyses; interpret the data; drafted and approved the manuscript. MT: designed the study; analyses; interpret the data and approved the manuscript.

The author report there was no conflicts of interest in this work.

©2018 Asifere, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.