International Journal of

eISSN: 2577-8269

Research Article Volume 1 Issue 3

1Department of General Medicine, Hirosaki University School of Medicine & Hospital, Hirosaki-shi, Japan

2Development of Community Medicine, Yonaguni Municipal Clinic, Japan

Correspondence: Tadashi Kobayashi, Department of General Medicine, Hirosaki University School of Medicine & Hospital, Hirosaki-shi 0368563, Japan, Tel +81-172-33-5161, Fax +81-172-39-8189

Received: October 20, 2017 | Published: November 2, 2017

Citation: Namiki H, Kobayashi T. Academic start-up support using tele-education improved self-esteem of a rural general physician. Int J Fam Commun Med. 2017;1(3):58-60. DOI: 10.15406/ijfcm.2017.01.00015

One of the key factors for rural physicians to continue their rural practices is continuing professional development (CPD). In Japan, academic activities have been reported to be a common type of CPD. The use of tele-education in academic activities has many advantages, although it has recently not been available in rural regions because of insufficient communication infrastructure. However, use of current freely available and information and communication technology (ICT) has allowed rural physicians to effectively connect with their supporters from afar. There are no reports at all that describe “academic start-up support” using tele-education for rural general physicians who have never engaged in any academic activities. We used mixed methods to investigate whether academic start-up support using tele-education to a rural general physician affected their CPD. We made three important findings. First, the rural physician as a learner could earn academic achievements. Second, his experience through the academic start-up based on his clinical practice, values, and philosophy as a rural physician could help him improve his self-esteem as a physician, and enhance his career. Third, this academic support based on his rural lifestyle and values could build good relationships with his community. We believe that using ICT to support rural physicians can improve their self-esteem, and promote CPD and the recruitment and retention of rural physicians in rural regions.

Keywords: Continuing professional development; Information and communication technology; Academic support; Social networking service; Lifestyle; Remote supporting system; Academic activities; Recruitment; Retention

CPD: Continuing Professional Development; ICT: Information and Communication Technology; MB/S: Megabytes per Second; SNS: Social Networking Service

One of the factors for rural physicians to continue their rural practices is continuing professional development (CPD).1 In Japan, academic training has been reported to be the most common type of CPD, followed in descending order by participation in academic meetings, academic activities including doctor of philosophy programs.2 The use of tele-education (remote-support systems using information and communication technology (ICT) in medical education) has many advantages (e.g., travel costs and time)1, and is rapidly developing. However, tele-education has not been available in many rural regions until recently because of insufficient communication infrastructure. In addition, no reports have described academic start-up support using tele-education “based on rural physicians’ values, ways of life and self-esteem”. We aimed to investigate the effects related to rural physicians’ self-esteem and CPD of first-time academic activities using tele-education by a general physician belonging to general medicine department of a university.

Our academic remote-support system using tele-education was provided from September 2016. The learner was a rural general physician (HN) with 11 years of rural practice after his graduation. He solely, as a single physician, ran the only clinic on the western-most isolated island in Japan (population: 1,700), which had insufficient communication infrastructure (maximum Internet line speed: download, 1.1 megabytes per second [MB/s]; upload, 0.9 MB/s). The instructor was a general physician (TK) working at the general medicine department of a university located approximately 2,400 km topographically from the island. Among freely available ICT, Zoom Video Communications (https://zoom.us/), software that allows users to share their personal computer screens at low line speeds, and Face book (http://www.facebook.com/), a social networking service (SNS), were used with only anonymous personal data. As evidence of the academic activities supported by this system, rural physician HN prepared his first 2, previously published3,4 English-language case reports. We evaluated the effects of this intervention using three types of analyses: qualitative analysis of semi-structured interview to the learner; quantitative analysis of the article-writing process and the number of consultations by method of communication; text-mining analysis (a method and system for dividing unconstrained collections of sentences into words and phrases using natural language analysis techniques and analyzing their occurrence frequency and correlation to extract useful information) of text data through SNS and e-mail for the consultations between the instructor and the learner.

First, as qualitative analysis, the instructor conducted a semi-structured interview with the learner (Table 1 & 2). The following effects on the learner were identified:

Summarized Comments |

Comments from Learner |

Improve Self-Esteem |

“I felt proud of myself in academic |

“I sincerely felt that my activities |

|

Improve Attitude of |

“I noticed the importance of clinical |

“I felt the depth of medical science.” |

|

Improve Activities in Community |

“Academic activities will be an achievement of a |

Improve recognition of Academic |

“I began to read articles more respectfully.” |

Realize the Effect of |

“I was more interested in medical problems, |

“The empathic attitude of the leader is |

|

Using ICT |

“I was able to do academic activities without anxiety |

Table 1 Semi-structured interview: Impacts on learner.

Summarized Comments |

Comments from Learner |

Improve Reliability of other Medical |

“This leads to better communications |

“It leads to better collaboration |

|

“The patient was pleased that |

|

Good versatility for other clinicians |

“This would be a good example for |

“The more communication facilities and software evolve, |

|

Increase interactions with |

“It became easier for medical staff to |

Table 2 Semi-structured interview: Influence on the learner’s relationship to his community.

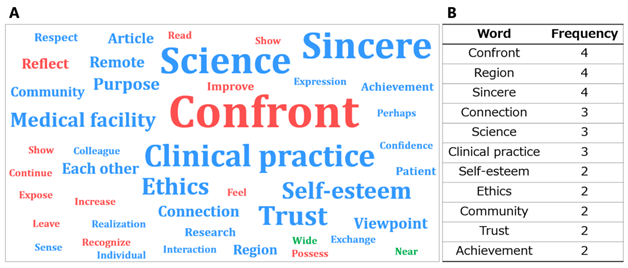

Second, as quantitative analysis, we counted the article-writing process and the number of each consultation by communication method (Table 3 & 4). Two case reports had almost same counts. Finally, as quantitative and qualitative analyses, we conducted text-mining analysis on the natural language text data for the consultations via SNS and e-mail between the instructor and the learner (Figure 1). The most commonly used words in the consultations were “Confront”, “region” and “sincere.”

Number of Consultations |

||

Communication Tool |

Case Report No.1 |

Case Report No.2 |

Total Consultation |

78 |

106 |

SNS and email |

65 |

102 |

Telephone |

10 |

3 |

Web Conference |

3 |

1 |

Table 3 The Number of Consultations by Case Report and Communication Tool.

Start Date (Number of Consultations) |

||

Process |

Case Report No.1 |

Case Report No.2 |

Case Selection |

2016.09.16 (8) |

2016.10.12 (4) |

Writing |

2016.09.17 (37) |

2016.10.12 (38) |

Submission |

2016.12.19 (3) |

2017.01.27 (18) |

Revision |

No revision |

2017.03.31 (7) |

Accept |

2017.01.12 (3) |

2017.04.04 (2) |

After Accepted |

2017.01.13 (8) |

2017.04.16 (10) |

After Published |

2017.01.16 (3) |

2017.04.17 (8) |

Duration of case selection and submission |

95 days |

108 days |

Table 4 The Article Writing Process and the Number of Consultations with the Instructor.

Figure 1 Text-mining analysis of text data of the learner through SNS and e-mail for the consultations between the learner and the instructor.

Figure 1a [left]: Three type of colors (word class) mean blue (noun), red (verb), and green (adjective). The size indicates how characteristic the word is in sentences. The words are displayed as larger size if they are distinctive, and as smaller size if they are likely to appear in any sentence tend to be displayed.

Figure 1b [right]: A list of the words used in order of frequency.

Three findings are apparent from the results. First, the learners in a rural region who have never engaged in any academic activities have earned academic achievements with ICT. Training for academic activity often includes actual face-to-face meetings. In our study, only internet-based meetings and communications were used. Unrestricted use of SNS and e-mail facilitated effective academic activities for the learner and the instructor, especially considering their distance and time considerations. Telephones were traditionally the useful communication tool for tele-education, but they require the instructor and the learner to be present at the same time. Therefore, SNS and e-mail have supplanted phone communications given their flexibility. In addition, freely available video communication software allows more data to be transmitted than by telephone, with distant users able to share their computer screens. ICT has thus diminished topographical restrictions and ameliorated time management, making certain academic activities possible even in rural regions. This is good news for rural physicians who face difficultly receiving face-to-face training.

Second, the learner’s experience through the academic start-up based on his clinical practice, values, and philosophy as a rural physician could help him improve his self-esteem as a physician, and enhance his career, attitudes surrounding life-long learning, and improve recognition of academic activities. Several reports pertaining to the effectiveness of CPD with tele-education have indicated that rural physicians’ needs are unique and varied.5 This has indicated that tele-education could be a robust support system for rural physicians and be instrumental in recruitment and retention. However, no reports have described remote-support system using tele-education with ICT based on the values of rural physicians’ ways of living life. Third, this academic support based on rural life values could foster good relationships with the learner’s community (Table 1 & 2). Figure 1 depicts an analysis of the learner’s feelings about the region and its people. Even in academic activities, the learners frequently used words such as regions, connections, and communities rather than academic-related words. This suggests that the support system for academic activities may be better for the region, the people, and himself.

These findings showed that our ICT support system based on the values of rural physicians’ way of life could help the learner to promote his own development through academic activities and to foster good relationships with the people and region around him. The system could be a good guide for his aspirations. We believe that the use of ICT to support rural physicians’ way of life could improve their self-esteem, and promote the CPD of physicians working in rural regions, and would contribute to the recruitment and retention of rural clinicians.

Our study indicates that a physician with no academic career who works in a rural region could earn academic achievements through tele-education using ICT. The provision of this support system based on the learner’s value helped him improve his self-esteem as a rural physician, enhance his career, and build good relationships with the people around him. We hope to improve self-esteem of rural physicians, and promote the CPD, recruitment, and retention of rural physicians striving in rural regions.

None.

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or this article.

©2017 Namiki, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.