International Journal of

eISSN: 2577-8269

Mini Review Volume 2 Issue 1

R&D Department, Laboratori Baldacci SPA, Italy

Correspondence: Marco Bertini, R&D Department, Laboratori Baldacci SPA, Italy, Tel +39 050 313271

Received: January 11, 2018 | Published: February 22, 2018

Citation: Bertini M, Is time for thinking to vaginal microbiome to prevent sexually transmitted diseases?. Int J Fam Commun Med. 2018;2(3):24-26. DOI: 10.15406/ijfcm.2018.02.00038

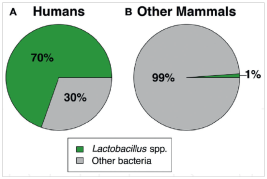

Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs) represents a major concern for public health systems worldwide: its prevalence is higher all over the world.1 In US about 12 millions of new cases occur each year and, surprisingly, also in developing countries STDs are very frequents beeing the second cause of health loss in childbearing women.1 Among all age groups adolescents between 10 and 19 years are the higher risk category: multiple sexual partners and unprotected sexual encounters seem to be the reason why of this relationship.1 The role of vaginal microbiome in humans is peculiar and unique between all the mammalian: the humans species are the only one with a relative abundance of lactobacillus species in vagina (more than 70%) if confronted with the other mammals that present not more than 1% of lactobacilli in vaginal microbiota (Figugr 1).1 During the past decade there has been an increasing interest in molecular-base, culture-independent techniques to study microbiome and the National Institute of Health has universally recognized the potential of molecular techniques to further understand human bacterial communities initiated the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) more than ten years ago (2007).2

The HMP targeted the genitourinary system because it has been well established for more than a century that a lot of bacteria are present within the human vagina and that the imbalance within the microbial environment could be associated with a lot of diseases.1 Many researches have demonstrated that modifications in the vaginal microbiome, such us in Bacterial Vaginosis, affect susceptibilty to gynecologic infections including cervicovaginitis, postoperative infections and HIV and HPV infections.3–7 Vaginal microbiome in healthy women is a lactobacilli-dominated environment that contribute to mantain pH under 4.5 and to produce lactic acid, hydrogen peroxyde, bacteriocins together with biosurfactants and co-aggregant activities able to counteract the growth of gram negative anaerobes bacteria such as G. vaginalis, Bacteroides, Mobiluncus spp and E. Coli: when this microenvironment changed and this equilibrium was broken (decreased of lactobacilli spp and increased in gram negative bacteria) vaginal pH increases determining Bacterial Vaginosis (BV).8,9

Increased in vaginal bacterial diversity. such as in BV, with the well-Known vaginal ecosystem modifications, seems to be associated with Sexually Transmitted gynecological infections: Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria Gonorrhea, Trichomonas vaginalis, Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) and Herpex Simplex Virus 2 (HSV-2) infections are substained and related to previous BV.10–13 So that treat BV, also in asymptomatic women, seems to be crucial for preventing STDs. Unfortunately the CDC (Center for Disease Control) recommended treatment regimen (metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days or metronidazole/clindamycin vaginal gel/cream one full application intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days) seems to be uneffective to control BV recurrences and mostly of the women treated according to CDC requirements have high recurrence rates in 6–12 months.14 Metronidazole or Clindamycin treatment do not prevent recurrences of BV infections because the healthy lactobacilli vaginal population is rarely reconstituted.14

Thus, there could be clinical advantages for the use of biotherapeutic agents (prebiotics/probiotics/synbiotics) together with CDC standard regimen for BV eradication and healthy vaginal microenvironment restoration.15 McFarland and Elmer defined Biotherapetic agents in 1995 as “living microorganisms that are used to prevent or treat human diseases by interacting with natural microbial ecology of the host”.15 Considering BV a predisponing factor for STDs acquisition and considering BV the worldwide prevalent vaginal infection in childbearing age women, it seems to be obvious the relationship between BV and Sexual Transmitted Diseases (STDs): controlling and normalizing vaginal microbiome in all childbearing age women could represent a relatively inexpensive and correct strategy to counteract STDs transmission and infections. Considering that CDC recommended therapies failed to control relapses of BV (almost 40% of relapses at 3 months and 50% of recurrences rate at 6 months)16 during the last years the use of biotherapeutic agents has been proposed and suggested to restore vaginal microbiome in BV women.15 The results belonging to the long-term use of a symbiotic (probiotic + prebiotic) vaginal tablets containing a selected lactobacillus populations (Lactobacillus rhamnosus BMX 54) plus a selected prebiotic (lactose) vaginally applied following CDC recommended regimen seems to be intriguing and support the use of this sinergistic and alternative therapy16–25 for a definitive restoration of the healthy vaginal microbiome able to counteract STDs infections and trasmission.

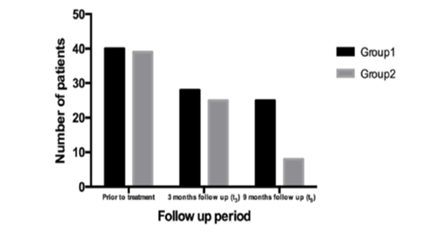

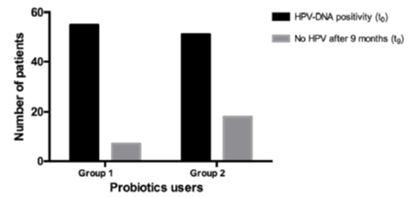

Controlled clinical trials performed in more than 800 women affected by BV and treated with standard of care (metronidazole) followed by a long-term course of this vaginal symbiotic clearly demonstrated a significative reduction of the recurrence rates of BV.16–25 Recently this synergistic approach (standard of care followed by Lactobacillus rhamnosus BMX 54 plus lactose vaginal tablet application) has shown to be useful also in controlling HPV infections in 117 women affected by bacterial or yeast infections and PAP smear abnormalities.25 This symbiotic topical implementation for at least six months have demonstrated to be able to re-establishing normal vaginal microflora (eubiosis) after standard of care treatment and, surprising, PAP smear alterations (Figure 2) or HPV clearance (Figure 3) have shown to significant improve in the group of women treated for long-term with Lactobacillus rhamnosus BMX 54 plus Lactose. These data support the use of long-term probiotics vaginal implementation after CDC recommended therapy not only to restore vaginal eubiosis but also to control HPV transmission and infection confirming that “is time to thinking to vaginal microbiome” to control STDs infection and that this simple and unexpensive approach could become “a keystone” in the STDs prevention and treatment.

Figure 1 Mean vaginal relative abundance of Lactobacillus spp. vs other bacteria in humans (A) and nonhumans (B).1

Figure 2 Trend of HPV abnormalities resolution in the two groups (group 1- short probiotics implimention group, n=60; group 2- long probiotics implemetion group, n= 57; p= 0.041.

Figure 3 HPV clearance at the end of follow up period (t9) in the two groups (group 1 – short probiotics implemention group, n=60, group 2- long probitics implemention group, n= 57), HPV clearence was significantly higher in the long term probiotics users than in the other groups (p=0.041), to before treatment; tq; after 9 months follow up.

None.

The author declare there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Bertini. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.