eISSN: 2471-0016

Research Article Volume 1 Issue 3

1Department Molecular Pathology and Oncology, Egypt

1Department Molecular Pathology and Oncology, Egypt

Correspondence: Bacem AE Ottoman, Department Molecular Pathology and Oncology, Egypt, Tel 2010 9518 9709

Received: January 01, 1971 | Published: November 25, 2015

Citation: Ottoman BAE. Diagnostic validity of minor salivary gland biopsies in behçet’s disease and Sjögren’s syndrome. Int Clin Pathol J. 2015;1(3):59–63. DOI: 10.15406/icpjl.2015.01.00015

Minor salivary gland biopsies were reported to be a sensitive diagnostic tool in a variety of systemic diseases. This paper depicts histological and immunohistological changes in Gilbert-Behçet syndrome (or Adamandiades-Behçet syndrome) and Sjögren’s syndrome. All are sealed as difficult-to-diagnose diseases. Four immunohistochemical markers were used: Cathepsin K, CD68, CD34, and CD16b. The findings could provide somehow clear-cut information for they could differentiate Gilbert-Behçet syndrome from Crohn’s disease. Histological results revealed very characteristic histological changes of minor salivary gland biopsy of the labial mucosa in GBS and Sjögren’s syndrome in contrast to normal mucosa. Minor salivary gland biopsies may be accordingly way useful in excluding and establishing the diagnosis of the above mentioned diseases without pursuing further invasive procedures.

Keywords: behçet’s disease, sjögren’s syndrome, rheumatic diseases, minor salivary gland biopsy, immunohistochemistry

Gilbert-Behçet syndrome (GBS) is a multisystem idiopathic inflammatory vacuities which evinces multi-systematic manifestaions of which mucosal, ocular, gastrointestinal and vascular manifestations come atop.1 GBS was alleged to be triggered by either an autoimmune process, infectious or environmental agents, attributed geographically to the old silk road, or even in a genetically predisposed individual.2,3 Taken together, ecological and infectious imprinting on a specific genetic background may contribute to the immune dysregulation which can increase, hypothetically, the propensity of developing GBS in liable population. Paradoxically, the remarkable negativity of ANA in GBS defies the hypothesis which attributes the actively circulating antibodies to be either autoantibodies or B cells. Therefore, recent workup hopes to prompt new speculations about the pathogenesis of GBS; toward setting up a dynamic treatment .

Sjögren's syndrome (SS), or Gougerot-Houwer-Sjögren syndrome, develops autoimmune epithelitis which is characterized by impressive lymphocytic infiltration of exocrine glands and extraglandular manfiestaions which affect, most often, lung, kidney, skin, nervous system with increased morbidity and high risk for developing lymphomas, particularly extraglandular large-B-cell-lymphoma . The Consensus report of the revised version of the European criteria, raised by the American-European Consensus Group, has defined diagnostic findings thereby SS can be established.5-8 To date, there are neither specific histological nor laboratory diagnostic hallmarks of GBS. Diagnosing SS is diagnosed based on correlating clinical, serological and some histological suggestive glandular findings. Yet, establishing a diagnosis of GBS, SS, or Crohn's syndrome (CS) is problematic. The International Study Group Criteria set is, therefore, the most widely used. Still, the proposed criteria have limitations, especially in diagnosing early GBS, indolent GBS, or differentiating GBS from CS.9-11 Complicating matters, clinical manifestations of the above mentioned elusive diseases appear metachronously rendering the clinical picture continuously dim. Newly, injecting a sterilized self-saliva has been suggested to diagnose GBS,12 while Prometheus test is claimed to be very suggestive of CS.13 This paper dictums a differentiating technique to discern such occult rheumatic diseases.

Eighteen volunteer cases were scheduled, after getting their informed consents, to incise a labial minor salivary gland under local anesthesia for diagnostic purposes. Of these, twelve cases were diagnosed with GBS, while six cases were diagnosed with SS. In addition to the H&E stained histological sections, serial cuts of 4μm thickness from paraffin-embedded specimen blocks were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in decreasing concentrations of ethanol. For antigen retrieval, sections were boiled in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 15![]() minutes in a pressure cooker after endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by immersing the sections in 3% H2O2 with methanol for 30

minutes in a pressure cooker after endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by immersing the sections in 3% H2O2 with methanol for 30![]() minutes. Treating with protein block serum at room temperature, sections were covered with primary antibodies; Cathepsin K (3F9, Abcam, Dilution 1:300), CD 16b, practical in the detection of neutrophils (48kD, Polyclonal, Dako, Dilution 1:500), CD 34, valuable in the recognition of hematopoietic precursors, capillary endothelia (105-120kD, Polyclonal, Dako, Dilution 1:500) and CD 68, (110kD, Dako, Dilution 1:500). Immunoreaction was performed using the labeled streptavidin-biotin method incubated overnight. For all antibodies, negativity or positivity was automatically evaluated, scaling at the “hot spot” in the selected fields. Area fraction was measured, using ImageJ software, to estimate the score of immunoreactivity. In doing so, (-) was designated for an immunoreactivity of 0-4%, (+) was labeled for 5-25%, (++) was denoted for 26-50%, (+++) was symbolized for 51-75%, and (++++) was assigned for 76-100%. Moreover, a total of 12 paraffin bocks, from recent archival cases of normal salivary glandular specimens, extracted from normal glandular tissues in minor surgeries, were contrasted to the studied pathological cases. The paraffin bocks were sectioned, 4μm thickness, and processed as aforementioned to be correspondingly stained by CD 16b, CD34, CD68 and Cathepsin-K.

minutes. Treating with protein block serum at room temperature, sections were covered with primary antibodies; Cathepsin K (3F9, Abcam, Dilution 1:300), CD 16b, practical in the detection of neutrophils (48kD, Polyclonal, Dako, Dilution 1:500), CD 34, valuable in the recognition of hematopoietic precursors, capillary endothelia (105-120kD, Polyclonal, Dako, Dilution 1:500) and CD 68, (110kD, Dako, Dilution 1:500). Immunoreaction was performed using the labeled streptavidin-biotin method incubated overnight. For all antibodies, negativity or positivity was automatically evaluated, scaling at the “hot spot” in the selected fields. Area fraction was measured, using ImageJ software, to estimate the score of immunoreactivity. In doing so, (-) was designated for an immunoreactivity of 0-4%, (+) was labeled for 5-25%, (++) was denoted for 26-50%, (+++) was symbolized for 51-75%, and (++++) was assigned for 76-100%. Moreover, a total of 12 paraffin bocks, from recent archival cases of normal salivary glandular specimens, extracted from normal glandular tissues in minor surgeries, were contrasted to the studied pathological cases. The paraffin bocks were sectioned, 4μm thickness, and processed as aforementioned to be correspondingly stained by CD 16b, CD34, CD68 and Cathepsin-K.

Clinical Findings

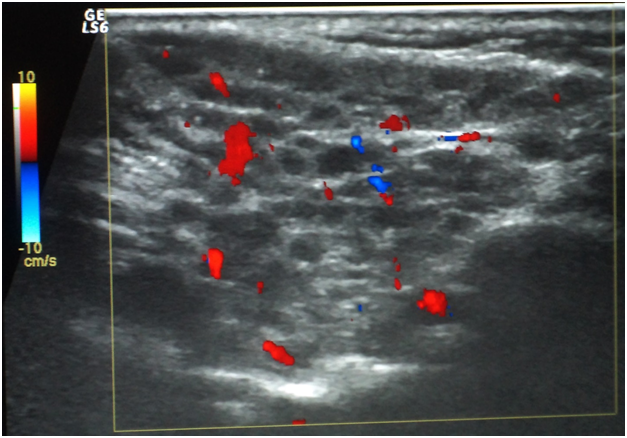

Oral ulcers, especially of the labial mucosa and tongue (Figure 1), were the commonest oral find in GBS while labial numbness, especially in the lower lip, enlarged major salivary glands, and xerotomia were very characteristic of SS. The commonest ocular manifestation in GBS, on the one hand, was intermittent uveitis whose severity ranged from mild to severe while cases of SS have presented typically xerophthalmia. No blindness was reported in the interval of the study as regards cases of GBS. Analogously, no cases of SS did run a transformation course into lymphoma or any other malignancy. Neuro-Behçet involvement and brain aneurysms in GBS, on the one hand, and the follow-up of SS cases, on the other hand, were assessed periodically by MRI. Normal images were obtained in the eighteen cases for this 3-year-old study (Table 1). Sonographically, superficial structures of the head and neck in GBS and SS were assessed. For cases of GBS, a single case has shown a subacute atherosclerosis in the carotid artery but no salient glandular changes were sonographically evident. However, cases of SS revealed a glandular parenchyma of heterogeneous echopattern. There were unmistakable bilaterlal diffuse miliary cystic cavities with patchy calcifications, spotting the underlying atrophic parenchyma. This has overtly promoted a “honeycomb” appearance on the sonograph. No other salient finding could be accentuated (Figure 2).

Epidemiology |

Behçet’s Disease |

Sjögren’s Syndrome |

|---|---|---|

Age |

42 (± 19.5) |

37 (± 14.4) |

Gender |

7 males / 5 females |

5 females / 1 male |

CLINICAL FINDINGS |

||

Oral findings |

Persistent/ recurrent oral ulceration |

Xerostomia , rampant dental caries , parotidomegaly |

Genital findings |

Persistent/ recurrent genital ulceration |

Vaginal dryness |

Ocular findings |

Uveitis , idiopathic pain |

Xerophthalmia |

Neurological findings |

Not evident |

Mild neuropathy |

GIT involvement |

Idiopathic pain |

Rarely involved |

SEROLOGY |

||

C-Reactive Protein |

Highly elevated |

Elevated |

ESR |

Highly elevated |

Elevated |

Anti-nuclear antibody |

Positive (5)- negative (7) |

Positive |

Self-Sterilized saliva pathergy test |

Positive |

Negative |

anti-Ro antibodies |

Negative |

Positive |

anti-La antibodies |

Negative |

Positive |

TREATMENT |

Hydrocorticosteroid |

Hydrocorticosteroid |

Table 1 Clinical parameters of the submitted cases of Behçet’s disease versus Sjögren’s syndrome

Histological findings

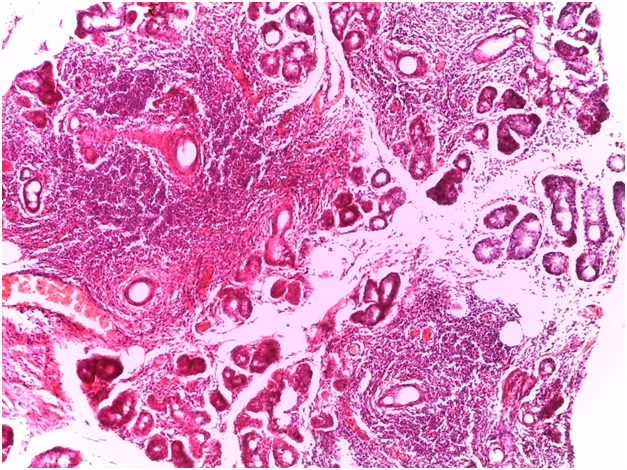

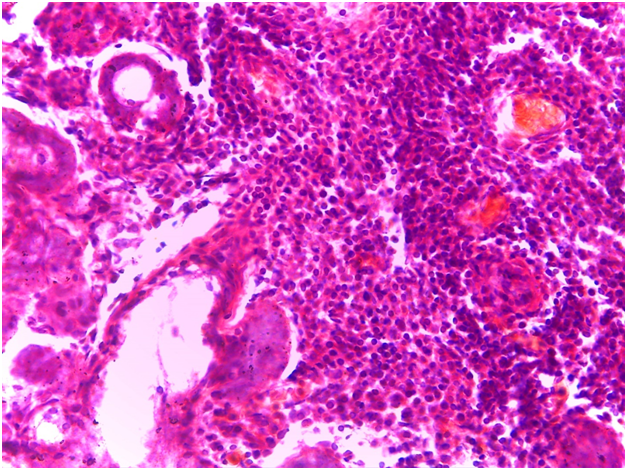

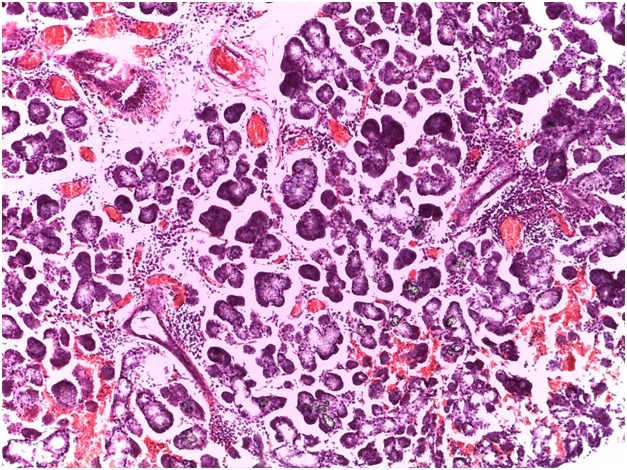

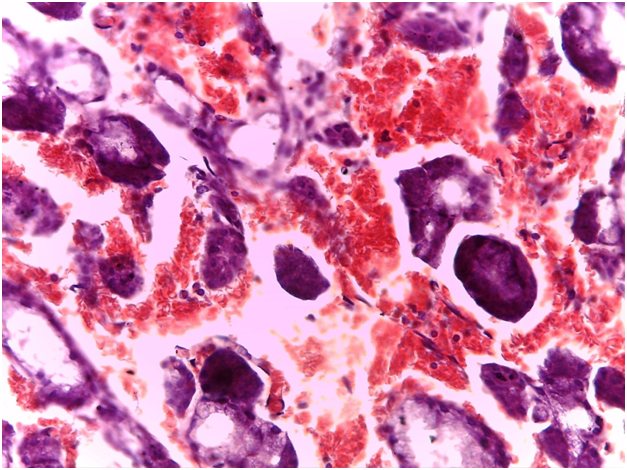

For Sjögren’s syndrome, salivary gland biopsy specimens have shown numerous lymphocytic foci in 4 mm2 (count > 50 lymphocytes per focus) within the glandular parenchyma. Acinar degeneration and few epimyoepithelial islands were detected. There was no substantial confluence of lymphocytes in a germinal-center-orientation within the submitted cases (Figure 3 & Figure 4). Focusing on characterizing any histopathological changes in GBS, the submitted cases of GBS revealed, in the asymptomatic glandular specimens, conspicuous perivascular and periductal infiltrations of neutrophils and macrophages. Moreover, vascularity was richer than that of normal mucosa whose vascular components were inconspicuous. Hemorrhagic spots, intervening extravasation of RBCs as well as dark acini, comparable to dust cells in smoking alveolitis, were also evident (Figure 5 & Figure 6).

Immunohistochemical findings

As regards to immunohistochemistry (IHC), all cases of GBS have expressed focal positivity that ranged from moderate (++) to strong expression (++++) for CD68 (Figure 7) and CD16b (Figure 8). These cases have revealed a natively strong immunoreactivity for CD34 (Figure 9). The twelve cases showed negative expression for cathepsin-K. By contrast, the representative slides of both SS and normal mucosa did not display any significant immunoreactivity for the above mentioned immunohistochemical markers. To contrast, the main histological and immunohistological findings were compiled in Table 2.

|

Normal |

Behçet’s disease |

Sjögren’s syndrome |

Gross picture of minor salivary gland |

Small-sized |

Swollen |

Swollen |

Ruptured blood vessel |

Nil |

Very often |

Sparse |

RBCs extravasation |

Nil |

Conspicuous |

Sometimes |

Inflammatory infiltrates |

Rare |

Periductal/ perivascular |

Periductal lymphocytes |

Dusty acini |

Absent |

Featured a remarkable range, including non-smokers |

Not evident |

CD68/ CD16b |

Negative |

Positive |

Negative |

Cathepsin- K |

Negative |

Negative |

Negative |

CD34 |

Negative |

Positive |

Negative |

Table 2 Histological and immunohistological findings in the submitted cases

Gilbert-Behçet syndrome is an enigmatic multisystemic disorder whose pathogenetic pathway may pertain to viral and/or genetic background. HLA-B51 gene in GBS patients, is alleged to be actively subsidized in the hyperactivity of neutrophils, so that it was considered, even more, a reliable diagnostic catch.14 Remarkably, increased neutrophil function in HLA-B51-positive GBS patients.15 Typical clinical features of SS include glandular manifestations of xerostomia, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, pharyngolaryngitis sicca, and bilateral parotidomegaly.6-8 In the present study, all were detected in the submitted cases of SS. Other manifestations included neurological involvement, numbness of the lower lip, decreased sweating and vaginal decreased secretions. Dyspareunia and glomerulonephritis, which may be cultivated subordinately, were not frequent.

Gilbert-Behçet syndrome characterizes no specific findings. The general histological pattern of neutrophilic infiltrations, lymphocyte aggregations of the surrounding vessels and vascular proliferations have been observed in biopsy specimens of oral apthae and genital ulcers. However, none of these is specific. Moreover, accumulation of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils as well as edema and leukocytoclasia occur at the site of the pathergy test within the first 12 hours.16,17 Again, this may hold true at any non-specific inflammatory site. This study appreciate the conspicuous perivascular and periductal infiltrations of neutrophils and macrophages, the rich intervening vascularity and the dusty acini in GBS. The characteristic lymphocytic within the atrophic glandular parenchyma, acinar degeneration and proliferations of epimyoepithelial islands were substantially remarkable in all labial salivary gland specimens of SS. This highlights the diagnostic validity of this biopsy in diagnosing such rheumatic diseases. Immunohistochemically, the moderate to strong expression for CD68 implied the high propensity of macrophages aggregations on the normally appearing acini; possibly attacking some bacterial strands with streptococcus sanguinis highly suspected. Similarly, the moderate to strong expression expression for CD16b indexed an affininty of perivascular and periductal neutrophilic infiltration. Staining strongly for CD34 has marked the proliferative incidence of endothelial vessels and increased intervening vascularity which signifies the vascular pathognomonicity of GBC. The negative expression for cathepsin-K emphasizes the non-granulomatous content of both GBS and SS. Reviewing the literature, caveats of exacerbating GBS encompassed, quite correctly, uveitis, aneurysms and CNS responses of which recurrent uveitis was considered highly striking for liability of visual loss, especially in the left eye.18-20 This find goes hand in hand with the present study therein uveitis was commonly observed.

The main treatment line in the literature is chiefly systematic with applying some topical medicaments. The archetypical treatment is the intake of corticosteroids especially in acute uveitis, and neurologic disease. Other treatment modalities combine steroids with colchicine, interferon (IFN)-α, cyclosporine, or azathioprine21 or recruit Dapsone .22 Colchicine,23 Azathioprine,24 interferon (IFN)-α25 and three anti-TNF-α compounds, infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept, have shown favorable results on preliminary tests.26,27 Recently, Davatchi et al,28 concluded that rituximab is efficient in severe ocular manifestations of GBS. In the present study, all cases were treated by corticosteroid. No other treatment modality could be evaluated.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2015 Ottoman. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.