eISSN: 2471-0016

Research Article Volume 4 Issue 4

1Department of Urology, Liaquat University of Medical and Health Sciences, Jamshoro, Pakistan

1Department of Urology, Liaquat University of Medical and Health Sciences, Jamshoro, Pakistan

2Jinnah Postgraduate Mdical Centre Karachi, Pakistan

2Jinnah Postgraduate Mdical Centre Karachi, Pakistan

Correspondence: Dr. Javed Altaf Jat, Department of Urology, Liaquat University of Medical and Health Sciences, Jamshoro, Pakistan

Received: January 01, 1971 | Published: April 28, 2017

Citation: Mal P, Altaf J, Ansari MR, et al. Determine the frequency of hepatorenal syndrome in patients with cirrhosis associated with hepatitis C. Int Clin Pathol J. 2017;4(4):104–109. DOI: 10.15406/icpjl.2017.04.00105

Introduction: Hepatorenal syndrome is a complex syndrome. In addition to severe derangement in renal function due to renal vasoconstriction, there is impairment in systemic hemodynamic, activation of renin-angiotensin and sympathetic nervous systems and antidiuretic hormone, vasoconstriction of brain, muscle and skin, and dilutional Hyponatraemia. This study shows frequency of HRS in patients with liver cirrhosis associated with HCV.

Objectives: To determine the frequency of Hepatorenal Syndrome in patients with cirrhosis associated with Hepatitis C virus presenting at Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre Karachi.

Material and methods: Cross sectional was conduct at Departments of Medicine and Nephrology Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Center, Karachi from 1st December 2007 to 30th May 2008. Data was collected from patients admitted in the medical and nephrology wards, through a pre-designed proforma. Informed consent was taken. Patients were included after meeting the inclusion criteria. After History and systemic examination investigations were done like blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, serum electrolytes, urine analysis, Anti HCV antibodies in all these patients.

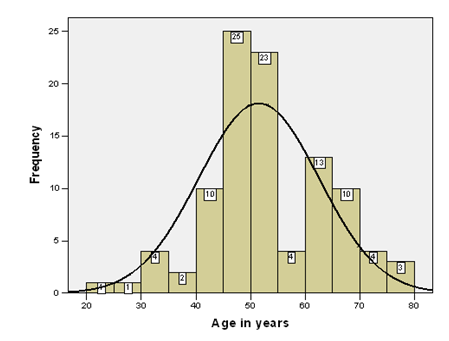

Results: A total of 100patients with liver cirrhosis were included in this study. Eighty five percent patients were between 40 to 70years. The average age of the patients was 51.53±11.01years (95%CI:49.35 to 11.01). Minimum age of the patients was 22years and maximum age was 80 years as mention in figure 1. Out of 100 patients, fifty six percent were male and 44% were female. Out of 100patients, 32patients (32%) had renal dysfunction manifested by serum creatinine level greater than and equal to 1.5mq/dl. Five patients (16.6%) of 32 were diagnosed as renal dysfunction due to hypovolumia, three were male and two were female. Five (16.6%) patients with renal dysfunction were diagnosed as case of sepsis, one was male and four were female. Three(9.4%) patients with renal dysfunction also have the history of nephrotoxic drugs. Similarly renal dysfunction were diagnosed as cases of UTI in 2(6.3%), obstructive uropathy 1(3.13%) and shock with history of fluid loss 1(3.13%). Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) was diagnosed in 12patients, which is 37.5%(12/32) and overall frequency of hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) was 12(12%) of all 100patients.

Keywords: hepatorenal syndrome, HCV, cirrhosis

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is a serious complication in the patient with cirrhosis and ascites, and is characterized by worsening azotemia with avid sodium retention and oliguria in the absence of identifiable specific causes of renal dysfunction1 and is the reason for 8-30% cases of acute kidney injury in cirrhotic patients.2 In Hepatorenal syndrome the histological appearance of the kidney is normal and the kidney often resume normal function following liver transplantation.3 This makes HRS a unique pathophysiological disorder that provides possibilities for studying the interplay between vasoconstrictor and vasodilator system of renal circulatory system. Renal failure is usually irreversible unless liver transplantation is being performed. Hepatorenal syndrome develops in the final phase of the disease. Cirrhosis of liver refers to a progressive, diffuse, fibrosing, nodular condition that disrupts the entire normal architecture of the liver.4 Cirrhosis and chronic liver failure are leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Viral hepatitis is serious health problem in Pakistan with prevalence rate of about 3-4% for hepatitis B5 and 4-6% for hepatitis C.6 Locally frequency of Hepatitis B & C viruses in patients with decompensated cirrhosis is 66% for Hepatitis C;20% for hepatitis B and 9% for both B & C.7

Settings

This is a prospective cross sectional and observational study. It was carried out at the Departments of Medicine and Nephrology Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre, Karachi between the duration of 1st December 2007 to 30th May 2008.

All patients of cirrhosis of liver with ascites associated with HCV aged between 15-60 years, admitted in medical and nephrology ward were enrolled in this study. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was confirmed by clinical examination revealing decrease liver span, Splenomegaly and presence of ascites, laboratory criteria which included blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, serum electrolytes, urine analysis, Anti HCV antibodies and ultrasound abdomen were done on these patients. A written consent was taken from patients or attendants (when patients were unable to give it). Assessment of all patients was done according to the criteria.

The patients who had serum creatinine 1.5mg/dl or more were worked up for the presence of Hepatorenal syndrome by following measures and investigation.

Diagnosis of HRS was made according to criteria proposed by international ascites club in 1996, which are

The major criteria are necessary for diagnosis of hepatorenal syndrome. Additional criteria are only supportive.

Statistical package for social science (SPSS-10) was used to analyze data. Frequency and percentage were computed for categorical variables like gender, diagnosis of renal dysfunction, hepatorenal syndrome, creatinine clearance, renal size. Mean and standard deviation were computed for quantitative variables like age, creatinine clearance, blood urea nitrogen, 24-hours urine, serum Na+, serum k+ and serum Cl- Independent sample t test was applied to compare mean between patients with and without hepatorenal syndrome for age, creatinine clearance, blood urea nitrogen, 24-hours urine, serum Na+, serum k+ and serum Cl- .

A total of 100 patients with liver cirrhosis were included in this study. Eighty five percent patients were between 40 to 70 years. Histogram of age distribution is presented in (Figure 1). The average age of the patients was 51.53±11.01 years (95%CI: 49.35 to 11.01). Minimum age of the patients was 22 years and maximum age was 80 years as mention in (Figure 1). Out of 100 patients, fifty six percent were male and 44% were female with 1.27: 1 male to female ratio as shown in (Figure 2). The average and 95% confidence interval of blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, 24-hours urine, serum Na+, serum K+ and serum Cl– are presented in (Table 1). Out of 100 patients, 32 patients (32%) had renal dysfunction manifested by serum creatinine level greater than and equal to 1.5mq/dl in which 17 (53.1%) were male and 15(46.9%) patients were female as shown in (Table 2). Different diagnosis of renal dysfunction in 32 patients is presented in (Table 3) five patients (15.6%) of 32 were diagnosed as renal dysfunction due to hypovolumeia, three were male and two were female. Five (15.6%) patients with renal dysfunction were diagnosed as case of sepsis, one was male and four were female. Three (9.4%) patients with renal dysfunction also have the history of nephrotoxic drugs and all were female and three (9.4%) had renal disease. Similarly renal dysfunction were diagnosed as cases of UTI in 2(6.3%), obstructive uropathy 1(3.13%) and shock with H/O fluid loss 1(3.13%).

Characteristics |

Mean ±SD |

95%CI |

Median(IQR) |

Max-Min |

Blood Urea Nitrogen |

25.05±19.41 |

21.20 to 28.9 |

15.0(23) |

80-8 |

Serum Creatinine (mg/dl) |

1.661±1.24 |

1.415 to 1.91 |

1.1(1.4) |

6.9-0.5 |

24-hours Urine (ml/dl) |

1136.3±503.2 |

1036.4 to 1236.1 |

1200(730) |

2200-250 |

Serum Electrolytes |

|

|

|

|

Serum Na+ |

135.44±5.64 |

134.32 to 136.56 |

136(7) |

148-120 |

Serum K+ |

3.946±.61 |

3.82 to 4.01 |

3.8(0.78) |

6.00-2.5 |

Serum Cl - |

101.83±5.42 |

100.75 to 12.9 |

101.0(7) |

115-88 |

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics of Clinical Characteristics of Patients N=100.

Serum Creatinine (mg/dl) |

Frequency |

Mean ± SD |

Male |

Female |

0.5 to 1.0 |

44(44%) |

0.81±0.15 |

25 |

19 |

1.1 to 1.4 |

24(24%) |

1.21±0.09 |

14 |

10 |

≥ 1.5 |

32(32%) |

3.19±1.12 |

17 |

15 |

Table 2 Nephrotoxin Creatinine Clearance N=100.

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) was diagnosed in 12 patients, which is 37.5% (12/32) among patients with renal dysfunction in which 8 were male and 4 patients were female as shown in table 3, and overall frequency of hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) was 12(12%) of all 100 patients with chronic liver disease and ascites as shown in (Figure 3). Average creatinine clearance was 17.34 ±4.66 mg/dl (95%CI: 14.38 to 20.29) in patients with hepatorenal syndrome. Frequency of creatinine clearance of 12 patients with hepatorenal syndrome is presented in (Table 4). Renal size of patients of cirrhosis with ascites with and without hepatorenal syndrome is presented in (Table 5). Average comparison of clinical-demographic feature of cases with and with out hepatorenal syndrome are also shown in (Table 6). Age, blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine were significantly highly with hepatorenal syndrome as compare to without hepatorenal syndrome. 24-hours Urine was significantly low with hepatorenal syndrome than without hepatorenal syndrome. Serum electrolytes were not observed significant. Decompensate liver disease is characterized by severe circulatory derangements including progressive splanchnic, vasodilatation and portal hypertension. These derangements result in several consequences of advanced liver failure, among them HRS is the most severe and frequent complications. It is estimated that at least 40% of patients with cirrhosis and ascites will develop HRS during the natural history of the disease. Cirrhosis is a serious and irreversible condition and is the end result of hepatocellular injury that leads to both fibrosis and nodular regeneration. Viral infection is the most common cause of cirrhosis world wide. The HCV is responsible for 60-70% of cases of cirrhosis. In the present study it is evident that renal function derangement was very common among patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Hepatorenal syndrome was the major culprit of renal function derangement. Other causes included were hypovolumia, sepsis, nephrotoxic drugs, and primary kidney disorders like UTI, obstructive uropathy and renal parynchymal disease. In my study out of 100 patients with cirrhosis and ascites due to chronic HCV infection, 32 patients had deranged renal function. Out of 32 patients five were diagnosed as renal dysfunction due to hypovolumia and achieved normal renal function after 1.5L of normal saline infusion and withdrawal of diuretics. Five (05) patients were in septicemia and SBP, improved renal function after appropriate antibiotics according to the culture and sensitivity of the offending organism. Two (03) patients with altered renal function had history of prolong use of nephrotoxic drugs like NSAIDS. Six (06) patients had deranged renal function due to primary renal cause like parynchymal renal disease, UTI and obstructive uropathy. Twelve (12) patients were diagnosed as hepatorenal syndrome (HRS). Hepatorenal syndrome is a disease of exclusion; it should be diagnosed only when all other causes of renal impairment are excluded.

Diagnosis |

Frequency |

Percentage |

Male |

Female |

HRS |

12 |

37.5% |

8 |

4 |

Hypovolumia |

5 |

15.6% |

3 |

2 |

Sepsis |

5 |

15.6% |

1 |

4 |

Renal Parynchymal Disease |

3 |

9.4% |

2 |

1 |

NephrotoxicDrug |

3 |

9.4% |

0 |

2 |

UTI |

2 |

6.3% |

1 |

1 |

Obstructive Uropathy |

1 |

3.13% |

1 |

0 |

Shock and H/O Fluid Loss |

1 |

3.13% |

0 |

1 |

Table 3 Nephrotoxin Diagnosis of the Patients with Cirrhosis.

Creatinine Clearance |

Frequency |

Percentage |

12.0 to 16.0 |

7 |

58.3% |

16.1 to 20.0 |

2 |

16.7% |

21.1 to 27 |

3 |

25% |

Total |

12 |

100% |

Table 4 Nephrotoxin Creatinine Clearance of Hepatorenal Syndrome.

Creatinine Clearance; Mean ± SD = 17.34 ± 4.66ml/min (95%CI: 14.38 to 20.29); Median (IQR) = 15.72 (5.6) ml/min; Minimum observation = 12.82 ml/min; Maximum Observation = 26.38 ml/min

Renal Size |

Hepatorenal Syndrome |

Total |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Positive |

Negative |

||

Normal |

10 |

81 |

91 |

Small |

2 |

4 |

6 |

Large |

0 |

3 |

3 |

Total |

12 |

88 |

100 |

Table 5 Renal Size of Patients of Cirrhosis with Ascites.

Characteristics |

HRS Positive |

HRS Negative |

P-Values |

|---|---|---|---|

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

||

Age (Years) |

58.75 ±11.42 |

50.55±10.64 |

0.015* |

Blood Urea Nitrogen |

54.92±13.14 |

20.98±16.34 |

0.0005* |

Serum Creatinine (mg/dl) |

3.633±0.80 |

1.288±0.93 |

0.0001* |

24-hours Urine (ml/d) |

474.17±263.8 |

1226.59±458.9 |

0.0001* |

Serum Electrolytes |

|

|

|

Serum Na+ |

127.92±6.8 |

136.47±4.63 |

0.51 |

Serum K+ |

4.1083±0.82 |

3.9239±0.58 |

0.33 |

Serum Cl - |

103.00±6.82 |

101.67±5.23 |

0.43 |

Table 6 Comparison of Clinical-Demographic Feature of Cases with and With Out Hepatorenal Syndrome.

In this study, HRS was labelled after fulfilment of criteria proposed by international ascites club followed by exclusion of other causes of renal dysfunction by clinical examination and investigations. Research work done at Civil Hospital Karachi by Raj Kumar, Raeefuddin Ahmed et al, in 2002 to find out the frequency of HRS in patients with cirrhosis and ascites. They included 240 patients in their study. Seventy six patients (31.6%) altered renal function. Among them 11 patients had primary renal disease. Six (6) patients were diagnosed to have renal dysfunction secondary to nephrotoxic drugs, and in seventeen (17) patients had renal dysfunction due to SBP. Six (6) patients had dehydration. While HRS was 15% among patients with cirrhosis disease and ascites.8 Gines A. Escorsell A et al, done study to see incidence, predictive factors and other variables among 234 non-azotemic patients with cirrhosis and ascites. They found that the probability of HRS was 18% at one year and 38% at 5 years.9-11 Vicente Arroyo describes in his article ‘Advances in the pathogenesis and treatment of type-1 and type-2 hepatorenal syndrome’ that the annual incidence of HRS in patients with cirrhosis and ascites is 8%.12 Richard Moreau has controversy about frequency of HRS. He compared two studies. One study conducted in North America, which was done in 3860 patients with ascites, HRS was diagnosed in less than 1% of these patients. Other study, which R. Moreau quoted, was of 234 non-azotemic patients with ascites showed that the probability of developing HRS was 20% and 40% at 1 and 5 years respectively. The reason for this controversial result is unclear.13-16

According to Michael Schepke’s study the HRS was present in about 40% of patients.17-22 While my study shows frequency of HRS 12%. Raj Kumar’s study reveals that HRS was present in 47.4% among cirrhotic patients with ascites who had altered renal function, while my study shows 37.5%. Michael Schepke’s result showed about altered renal function secondary to drugs was about 19% in cirrhotic patients with ascites and Dr. Raj Kumar’s study reveal 7.6% while my study shows 6.3%. Raj Kumar’s results share that altered renal function due to the SBP or infection is about 22.3%, while 7.8% of patients having prerenal failure due to dehydration and Micheal Schepke’s results shows abnormalities in renal functions in cirrhotic patients with ascites secondary to prerenal failure and infection were approximately 15%. My study highlights renal functions derangements due to hypovolumia and sepsis were 16.6% respectively. The cause of altered renal function due to primary renal disease was about 23% in Michael Schepke’s study, 14.4% in Dr. Raj Kumar’s study, while in my study it is about 18.83%. The results of my study nearly correlate with the results of Michael Schepke and Raj Kumar. Thus it is wise to recommend that those patients with ascites and cirrhosis, who develop SBP and renal function derangement, should be managed aggressively with close monitoring to restore volume status and renal functions. Intravenous albumin 1.5g/kg/day should be given as part of management.23-31 Other precipitating factors need to be avoided like large volume paracentesis without plasma expansion with albumin, diuretics. Gastrointestinal Bleeding and other bacterial infections should be treated promptly.

Hepatorenal syndrome is a major clinical turning point in patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Although the most characteristic feature of the syndrome is a renal failure due to renal vasoconstriction. The data collected through this study showed that Hepatorenal syndrome was the most common cause of renal impairment in these patients followed by other causes like hypovolumia, sepsis, primary renal disease, nephrotoxic drugs, obstructive uropathy and urinary tract infection.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Mal, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.