eISSN: 2576-4497

Research Article Volume 2 Issue 2

1Department of Nursing, University of Gondar, Ethiopia

2Department of Public Health, University of Gondar school of public health, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Mengistu Mekonnen Kelkay, Department of Nursing, University of Gondar, Po box 196, north Gondar, Ethiopia

Received: February 13, 2018 | Published: April 23, 2018

Citation: Kelkay MM, Kassa H, Birhanu Z, et al. A cross sectional study on knowledge, practice and associated factors towards basic life support among nurses working in amhara region referral hospitals, northwest Ethiopia, 2016. Hos Pal Med Int Jnl. 2018;2(2):123–130. DOI: 10.15406/hpmij.2018.02.00070

Introduction: Sudden cardiac arrest is one of the most frequent causes of death in the world; however, timely provision of basic life support (BLS) by knowledgeable and skilful health professionals will make an important contribution to reduce avoidable death and disability.

Methods: An institution based cross-sectional study was carried out in April 2016 among 397 nurses working in Gondar University Hospital and Bahirdar Referral Hospitals. Multivariate analysis using logistic regression model was used to analyze the association between knowledge and practice of basic life support with potential predictor variables. AOR and 95% CI were computed to identify predictor variables.

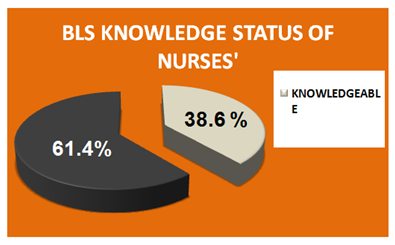

Result: A total of 388 nurses participated in the study with a response rate of 97.7 among the study participants, 38.6% and 28.4% had good knowledge and good practice of BLS, respectively. Educational status, assigned place, training, and previous exposure were significantly associated with knowledge of BLS. With regard to practice of BLS: training, previous exposure, confidence and knowledge were factors associated with practice of BLS at (p≤0.05).

Conclusion: In general, the knowledge and practice of BLS among nurses were low. Thus subsequent training and education is mandatory to achieve the desired outcome.

Keywords: basic life support, nurse, practice, EthiopiaSudden cardiac arrest is one of the most frequent causes of death in the world,1 and it is an important acute emergency situation that occurs in hospital settings with high levels of mortality risk. In addition, survival and complete physiological recovery rates following in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) are poor in all age groups. Medical authorities reported that a victim of cardiac arrest has the best chance of survival without neurological damage if care is received within 3-5 minutes of occurrence. Nursing staff plays a central role in the effective management of the IHCA as they are often the first medical staff to arrive to patient with IHCA.2

Cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA) poses a severe threat to life; cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) represents a challenge for research and assessment by nurses and their team.3 Cardiac arrests and accidents are the most common emergencies in adult, children, and neonates, and have severe consequences; however, because of the change recommended in 2015 guideline, immediate recognition of sudden cardiac arrest and activation of the emergency response system, early CPR, and rapid defibrillation with an automated external defibrillator (AED), the high mortality associated with cardiac arrest can be easily prevented and managed.4 Resuscitation skills can restore the life or consciousness of one apparently dead.5 Especially when BLS initiated within the first minute of cardiac arrest, the survival to discharge after in hospital cardiac arrest will be doubled.6 Because survival after cardio pulmonary arrest is low and depends on early intervention and quality of CPR, since sudden cardiac death is particularly a time-critical event.7

Knowing how to correctly perform BLS and the Advanced Life Support (ALS) are among the most important determining factors of the cardiopulmonary success rates (cite). Therefore, it is critical for nurses to know and perform BLS to tackle acute medical emergencies.8 Thus improving the knowledge and practice of BLS among nurses is critical in the final outcome of acute emergency situations. However, because of poor knowledge and practice of the health care professionals towards BLS, deaths that could have been prevented even by inexpensive and simple procedures occur.

Nurses working in the hospital setting are expected to deal with cardiac arrest in an expert manner, since they frequently witness cardiac arrest. However, studies indicate that CPR skills of nurses are often poor. As a result nursing professionals need to have updated technical knowledge and practical skills to cardiac arrest manoeuvres, since proper practice of the techniques enables a person to effectively resuscitate a victim.5,9 Basic Life Support forms a foundation level of care for treating patient particularly with life threatening illnesses or injuries. Therefore nurses are supposed to be capable to resuscitate from their first posting.10 Ideally everyone should know BLS and/or CPR but the scientific knowledge, and proper techniques of CPR of nurses is a critical component that makes a difference between life and death especially after cardiac and respiratory arrest.

Over all provision of emergency care like BLS by knowledgeable and skilful health professionals in the hospital setting will make an important contribution to reduce avoidable death and disability.11 In this respect, the action of nursing in health services in general and CPR in particular for those who need an emergency care has a remarkable contribution to a better outcome encouraging to the survival of the person.12 Therefore, the result of this study will be useful for future planning, conducting programs, and design effective strategies on BLS program in hospitals.

Study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted in April 2016 among 397 nurses working in Gondar University Hospital and Bahirdar Referral Hospital. Data were collected using self-administered questionnaires. Data were entered to Epi Info version 3.5.3 and analyzed using SPSS version 20. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify variables having significant association with the dependant variables. All explanatory variables with p-value of <0.2 from bivariate logistic regression model were fitted in the multivariate logistic regression to see the effect of each variable with the dependent variables. Finally in the multivariate logistic regression analysis the variables which have statistically significant association were identified on the basis of OR with 95%CI. Crude and adjusted odd’s ratios at 95 % confidence interval were used to show the strength of association

Demographic characteristics of nurses

The total numbers of study participants were 388 with a response rate of 97.7%. More than half of the participants were females (52.6%). The mean age of the respondents was 28.82 years, SD=6.1. Nearly two-thirds of the participants (62.9%) had bachelors’ degree (BSc) in nursing. Nearly half of the respondents, 47.9%, had 1-5 years of clinical experience, and 68.3% of the participants were assigned in different wards, such as medical, surgical and paediatric wards (Table 1).

Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

Sex |

|

|

Male |

184 |

47.4 |

Female |

204 |

52.6 |

Age |

|

|

20-29 |

246 |

63.4 |

30-39 |

110 |

28.4 |

≥40 |

32 |

8.2 |

Educational status |

|

|

Diploma nurse |

144 |

37.1 |

Bachelor degree |

244 |

62.9 |

Year of expierance |

|

|

<1 year |

52 |

13.4 |

1-5 year |

186 |

47.9 |

5-10 year |

95 |

24.5 |

≥10 year |

55 |

14.2 |

Assigned Place |

|

|

OPD |

103 |

26.5 |

Ward |

265 |

68.3 |

ICU |

20 |

5.2 |

Table 1 Socio demographic characteristics of Nurses at Gondar University and Bahirdar referral hospitals, Amhara region, Northwest Ethiopia, April 2016

NB: wards, medical, surgical, pediatric and gynecology ward

Other factor related characteristics of the study participants

More than two-thirds (68.6%) of study participants had not ever had BLS training. Only 7.7%, and 23.7% of the participant had received pre-service (training given before graduation) and in-service training (training given while working after graduation) respectively. Two hundred twenty four (57.73%) of the study participants have been involved in patient resuscitation (Table 2).

Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Resuscitation training |

|||

Yes |

122 |

31.4 |

|

No |

266 |

68.6 |

|

Exposure to cardiac Arrest patients |

Never |

164 |

42.3 |

1-5 times |

105 |

27 |

|

≥5 times |

119 |

30.7 |

|

Table 2 Other factors related to knowledge and practice of basic life support among Nurses working in Gondar and Bahirdar Referral Hospital, Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia, April 2016

Knowledge of the study participants towards basic life support

Only 38.6% of study participants had good knowledge towards BLS. Two hundred thirty-eight (61.4%) of the respondents were reported not having knowledge about how to perform BLS (Figure 1). The mean knowledge score of the participants was 9.17 with a median score of 9.00 (ranged 3 to 20 from 22 knowledge questions).The most correctly answered question was about the abbreviation of BLS which comprises of 73.2%, followed by questions stating the best choice to describe the technique to perform chest compression 67.3%, while the least correctly answered question was about opening the air way of a 7 year old boy with bleeding from his forehead following car accident 16.2% (Table 3).

Figure 1 BLS Knowledge status of the Nurses working in Gondar and Bahirdar Referral Hospitals, Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia, April, 2016.

No |

Questions |

Freq |

% |

1 |

Abbreviation of BLS |

284 |

73.2 |

2 |

The sequence that comes first in BLS |

113 |

29.1 |

3 |

The response when we see someone is unresponsive( you are alone) |

104 |

26.8 |

4 |

After you remove un responsive child from the bottom of a swimming pool, when should you call a help |

190 |

49.0 |

5 |

How should you open the air way of unresponsive victim with no sign of trauma |

193 |

49.7 |

6 |

Ways of checking breathing in unresponsive victim |

144 |

37.1 |

7 |

To achieve an adequate depth of chest compression for a 5 years old children we use |

148 |

38.1 |

8 |

The person providing chest compressions should change about every___minute |

197 |

50.8 |

9 |

The exact place to check the circulation (sign of life ) in child >1 years |

192 |

49.5 |

10 |

How often should you provide rescue breaths for the child? |

134 |

34.5 |

11 |

How many initial breaths should you give for unresponsive victims (you are performing 2 rescue CPR) |

97 |

25.0 |

12 |

The best explanation for the positive effects of rescue breaths? |

200 |

51.5 |

13 |

The preferred site for a pulse check in an adult victim who is unresponsive is? |

143 |

36.9 |

14 |

Where should you place your hands on the chest of a victim when you are performing chest compressions? |

147 |

37.9 |

15 |

You are performing CPR on an unresponsive man, What is your ratio of compressions to ventilations? |

192 |

49.5 |

16 |

The correct rate/speed you should use to perform compressions for an adult victim of cardiac arrest? |

122 |

31.4 |

17 |

Choice of technique to perform chest compressions on infants? |

261 |

67.3 |

18 |

What is the compression to ventilation ratio when you resuscitate a new born baby? |

180 |

46.4 |

19 |

For how long will you check sign of life in arrested patient |

116 |

29.9 |

20 |

How do your chest compressions and rescue breathing help the victim of sudden cardiac arrest? |

246 |

63.4 |

21 |

How should you open the air way of a 7 years boy with bleeding from his forehead following car accident |

63 |

16.2 |

22 |

What will be the first step for unresponsive victims but spontaneous breathing removed from submerged water |

103 |

26.5 |

Table 3 Responses of Nurses for 22 BLS knowledge questions in Gondar and Bahirdar Referral Hospitals, Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia, April, 2016

Practice of nurses towards basic life support

This study revealed that 71.6% of the participants had poor BLS practice. Only 31.4% of the respondents received BLS training, of which, almost 25% took training before their graduation as a pre-service training and 75.41% after their graduation as an in-service training. The rest of the participants had never had any resuscitation training towards BLS. Regardless of shortage of resuscitation training, nearly 43% of the respondents were involved in patient resuscitation during their nursing experience. Concerning the involvement in patient resuscitation, 62.87% and 37.12% of participants were involved with frequency of 1-5 and ≥5 times respectively. Participants also asked if they were involved as a team leader during patient resuscitation and their confidence in performing BLS maneuvers, only 70(18.04%) participants were involved as a team leader and majority of them 247(63.7%) replied that, they were not confident in performing BLS procedures.

Factors associated with knowledge of nurses towards basic life support

In the unadjusted binary logistic regression analysis: age of the respondents, educational status, year of clinical experience, current assigned/work place, resuscitation training and previous exposure to BLS manoeuvres’ were the variables’ that are found to be associated with the Knowledge of BLS. Whereas, in the multivariate binary logistic regression analysis, educational status, year of experience, and current assigned place from socio demographic characteristics, and only resuscitation training, and previous exposure to cardiac arrest from other factor related characteristics of the study participants were the variables significantly associated with the knowledge of BLS at p-value of ≤0.05 (Table 4).

Variables |

Knowledge |

OR (95%CI) |

|||

Yes n (%) |

No n (%) |

Crude |

Adjusted |

||

Sex |

Male |

71 (38.6) |

113 (61.4) |

1 |

|

Female |

79 (38.7) |

125 (61.3) |

0.99(.66,1.49) |

|

|

Age in years |

20-29 |

72(a29.3) |

174(70.7) |

1 |

1 |

30-39 |

52(47.3) |

58(52.7) |

2.16(1.36, 3.44)* |

0.98(0.48, 2.01) |

|

≥ 40 |

26(81.2) |

6(18.8) |

10.47(4.13, 26.52)* |

1.56(0.31, 7.69) |

|

Educational status |

Diploma |

23 (16.0) |

121 (84.0) |

1 |

1 |

Degree |

127 (52.0) |

117 (48.0) |

5.71(3.42, 9.52)* |

6.96(3.36, 14.42)* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Year of experience |

< 1year |

6(11.5) |

46(88.5) |

1 |

1 |

1-5 years |

51(27.4) |

135(72.6) |

2.89(1.16, 7.19)* |

3.44(1.03, 11.44)* |

|

5-10 year |

46(48.4) |

49(51.6) |

7.19,(2.8, 18.44)* |

6.82(1.93, 24.12)* |

|

>10years |

47(85.5) |

8(14.5) |

45(14.4, 139)* |

30(6.94, 136.66)* |

|

Assigned place |

OPD |

26 (25.2) |

77(74.8) |

1 |

1 |

WARD |

112 (42.3) |

153 (57.7) |

2.16(1.3, 3.59)* |

3.24(1.49, 7.06)* |

|

ICU |

12 (60.0) |

8 (40.0) |

4.44(1.63,12.06)* |

4.67(1.09, 19.86)* |

|

Training |

Yes |

90 (73.8) |

32 (26.2) |

9.65 (5.88, 15.84)* |

5.63(2.9, 10.92)* |

No |

60 (22.6) |

206 (77.4) |

1 |

1 |

|

Exposure to BLS |

Yes |

135 (60.3) |

89 (39.7) |

15.19(9.15, 25.21) |

10.11(5.33, 19.19)* |

No |

15(9.1) |

149 (90.9) |

1 |

1 |

|

Table 4 Bivariate and Multivariate analysis of factor associated with the knowledge of nurses towards basic life support in Gondar and Bahirdar referral hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia, April 2016

Those nurses who had first degree in nursing were 6.96 times more likely to be knowledgeable as compared to diploma holder nurses [AOR=6.96, 95%CI (3.36, 14.42)] Study participants who had 5-10 years of clinical experience were 6.82 times more likely to be knowledgeable as compared to those who had lesser experience [AOR=6.82, (1.93, 24.12)]. Nurses who were working in medical ICU where very critical cases are being admitted and treated had about 5 times more likely to be knowledgeable as compared to nurses working in OPD [AOR=4.67, 95%CI (1.09, 19.86)]. Similarly nurses working in different wards were 3 times more knowledgeable than nurses working in the OPD. Nurses having BLS training had 5.63 times more likely to be knowledgeable than those who didn’t take part in resuscitation training activities [AOR=5.63, 95% CI (2.9, 10.92)]. Those nurses who were previously performed BLS maneuvers are 10.11 times more likely to utilized their knowledge as compared to those nurses who didn’t encountered cardiac arrest/suddenly collapsed patient [AOR=10.11, 95% CI (5.33, 19.19)] (Table 4).

Factors associated with practice of basic life support

On Bivariate logistic regression analysis: age, knowledge of BLS, assigned place, resuscitation training, previous exposure to cardiac arrest patient and self confidence towards performing BLS were factors associated with the dependent variable; however, in the multivariate logistic regression analysis only knowledge, resuscitation training, previous exposure and confidence in performing BLS were factors found to be significantly associated with practice of nurses towards BLS at p-value of <0.05. The present study revealed that knowledgeable nurses were two times more likely to perform BLS skills as compared to those with in adequate knowledge [AOR=1.94, 95%CI 1.02, (3.77)]. Nurses’ who received BLS training were 3 times more likely to practice BLS skills than those who had had no training either before or after graduation[AOR=3.12, 95% CI (1.72, 5.66)]. Nurses’ who had previous exposure to BLS skills were 7.8 times more likely to practice BLS as compared to those who didn’t exposed [AOR=7.8, 95% CI (4.2, 14.78)]. Similarly nurses who replied as they were confident in performing BLS had 7.4 times more likely to practiced BLS skills than those who were not confident [AOR=7.4, 95% CI (4.1, 13.35)] (Table 5).

Variables |

Practice |

COR, CI |

AOR, CI |

||

Yes n(%) |

No n(%) |

||||

Sex |

Male |

51 (27.7) |

133 (72.3) |

0.94(0.60,1.46) |

|

Female |

59 (28.9) |

145 (71.1) |

1 |

||

Age |

20-29 |

58 (23.6) |

188 (76.4) |

1 |

1 |

30-39 |

39 (35.5) |

71 (64.5) |

1.78(1.09, 2.90)* |

1.08(0.54, 2.18) |

|

≥40 |

13 (40.6) |

19 (59.4) |

2.21 (1.03, 4.76)* |

0.65(0.17, 2.39) |

|

Educational status |

Diploma |

33(22.9) |

111(77.1) |

1 |

1 |

Bachelor |

77 (31.6) |

167 (68.4) |

1.55(0.96, 2.48) |

0.67(0.34, 1.31) |

|

Year of experience |

<1year |

7 (13.5) |

45 (86.5) |

1 |

1 |

1-5 years |

43 (23.1) |

143 (76.9) |

1.93(0.81, 4.59) |

1.15(0.39, 3.38) |

|

5-10 years |

34 (35.8) |

61 (64.2) |

3.58(1.45, 8.81)* |

1.5(0.46, 4.88) |

|

>10 years |

26 (47.3) |

29 (52.7) |

5.76(2.2, 14.9)* |

1.38(0.32, 5.93) |

|

Assigned place |

OPD |

20 (19.4) |

83 (80.6) |

1 |

1 |

WARD |

83 (31.3) |

182 (68.7) |

1.89 (1.08, 3.29)* |

1.31(0.69, 2.71) |

|

ICU |

7 (35.0) |

13 (65.0) |

2.23 (0.78, 6.32) |

0.88(0.25, 3.06) |

|

Training |

Yes |

69 (56.6) |

53 (43.4) |

5.49(3.67, 9.6)* |

3.3(1.79, 6.1)* |

No |

41 (15.4) |

225 (84.6) |

1 |

1 |

|

Exposure to Cardiac arrest |

Yes |

97(43.3) |

127 (56.7) |

8.71(5.17, 14.67)* |

4.51(2.12, 9.56)* |

No |

13(7.9) |

151(92.1) |

1 |

1 |

|

Confidence |

Yes |

80(56.7) |

61(43.3) |

7.8(4.76, 12.79)* |

6.5(3.69, 11.61)* |

No |

30(12.1) |

217(87.9) |

1 |

1 |

|

Knowledge |

Yes |

80(53.3) |

70(46.7) |

7.92(4.8, 13.1)* |

1.94(1.002, 3.77)* |

No |

30(12.6) |

208(87.4) |

1 |

1 |

|

Table 5 Bivariate and multivariate analysis of factor associated with practice on basic life support, in Gondar and Bahirdar referral hospitals, Amhara region, Northwest Ethiopia, April, 2016

NB: *, significant at p-value <0.05

Nurses are the central part of the health care system and they are believed to be knowledgeable and competent in caring for patients. In the hospital setting, most of the time the deterioration of patient is gradual and potentially preventable if and only if nurses monitor their patient closely using their knowledge and skill of resuscitation. BLS is an important medical procedure which is critically required for individuals who face sudden cardiac arrest or those who suddenly lose their consciousness. Even though cardiac arrest and sudden loss of consciousness frequently occurs in hospitalized patients, this condition may occur in normal individual who doesn’t encounter cardiac arrest. Hence BLS knowledge and skill is extremely important to prevent and return the life of suddenly collapsed patient, so that nurse should become knowledgeable and skilful in delivering quality BLS.

In the present study, the BLS knowledge and skill of nurses do not conform to western standards and the practical aspect/the clinical skills of BLS were not assessed rather their perceived competency towards BLS were assessed. In general the knowledge and practice score of the study participants was found to be poor, as it was suggested by a mean and ±SD total score of 9.17±3.3 and 3.6±1.5 respectively from a total of 22 knowledge and 8 practice questions. Only few nurses could answer questions like how should you open the air way of victim who had head injury, how many initial breath should you give for unresponsive victims and the first step for unresponsive victims, removed from submerged water with spontaneous breathing.13

The current study revealed that the knowledge of nurses towards basic life support was 38.6%; this finding was lower than study done in Brazil study (64.7%)14 Kuwait (42.9%)15 and Bahrain (42%).16 The possible reason might be due to the interventional and involvement of higher proportion of nurses working in the intensive care unit in Brazil study. Only registered nurses received BLS learning session were included in Kuwait study and the difference in selection of study subjects in Bahrain study. However this finding was higher than study conducted in South Africa (11%).17 The possible explanation might be, in the South Africa study the highest cut off point 80% were used as a pass mark to determine the level of nurses’ knowledge.

There is an assumption that nurses who become proficient in BLS will be able to respond immediately and appropriately for victims who need an emergency resuscitation,18 therefore it is important to have an in-service education for nurses to improve their knowledge as well as their skills of providing basic life support. This study also agrees with the above assumption, since the educational status of nurses and their knowledge levels was found to be significantly associated. Nurses who have a bachelor degree in nursing were nearly seven times more likely to be knowledgeable as compared to nurses who had diploma in nursing towards basic life support. This contradicts with study done in Kuwait that revealed the theoretical knowledge of nurses were not influenced by educational status/qualification.15 The possible reason for this might be in Kuwait nurses of having different educational status are subjected to take periodic test towards CPR so as to keep them updated as a result their knowledge status were not affected.

Respondents who were assigned in the medical ICU had 4.67 times more likely to be knowledgeable as compared to respondents assigned in OPD. This is in agreement with study carried out in Brazil, and Turkey, by stating professionals who were working in the ICU had a highest mean score than among nurses working in OPD and ward.14,19 The idea is also well supported by UK resuscitation guideline 2010 which states that staff in critical care and emergency medicine may have more advanced resuscitation knowledge and skill than those who are not regularly involved resuscitation in their normal clinical role.20 Those nurses who were previously exposed and performed BLS had 10.11 times more likelihood of scoring better knowledge than those who were not exposed. Similar finding also reported in Athens Greece, it stated as nurses encountered more than 5 cardiac arrest, scored significantly higher than those with no previous exposure.21

To have a greatest resuscitation success periodical BLS resuscitation training is imperative in nursing practice.15 Resuscitation training improves the quality of BLS knowledge and performance of the nurses’;22 however, in this study only 31.4% of nurses were involved in resuscitation training. From this 24.6% had attained training before graduation, where as 75.4% had attained after graduation. Despite the fact that nurses had received some level of BLS training, in this study the result showed that highest proportion 61.3% of the participants scored poor knowledge. Nurses who had had previous resuscitation training towards basic life support are 5.4 times more likely to be knowledgeable than those without attending training. This indicates that training is compulsory in all nurse training institutions to improve the knowledge of nurses and to make them more proficient and skilful in the clinical area. This idea is also supported by study carried out in UK,23 and in Japan [44], these two studies magnifies the importance of interval or periodic resuscitation training on prevention of knowledge and skill deterioration.

Similarly study done in Pakistan also concluded that the knowledge of trained personnel is better than those of untrained.24 On the contrary studies in Kuwait and Greece Hospital revealed that, there were no significant difference in the knowledge score of those who had training compared to those who had not participated in resuscitation training.25 The possible justification for this is, the nurses in these two studies are accustomed to take interval knowledge and skill checking tests, this habit of nurses makes them more familiarized with BLS therefore their knowledge might not be influenced by training. Previous exposure to cardiac arrest patient significantly influenced the BLS knowledge of nurses. Those who were involved in resuscitation had significantly higher score than those who were not involved; this is in agreement with Nepal study.26 In this research self confidence has been associated with practice, similar result have been reported.27 The quality of BLS resuscitation skills of nurses has significant impact on cardiac arrest victim; inadequate skill of nurses towards BLS resuscitation skills has contributed to poor outcome of cardiac arrest victims. When patient face a life threatening events such as sudden loss of consciousness, and cardiopulmonary arrest, they often became dependant on the competency and skill of the nurses,28–35 because more often nurses are the first responders in the hospital setting when emergencies arise.

In the current study the level of practice of nurses towards BLS was 28.4%. This finding is lower than study carried out in Australia (38.4%)19 and Kuwait (52.0%).15,36–40 The possible difference could be the tools which the authors in Australia study used peer to rate the actual practice of nurses, this might influence the result, and in Kuwait study only registered nurses were included. Early initiation and timely provision of BLS are the critical elements which the nurses has suppose to do it, therefore the nurse has to be the competency so as to deliver high quality BLS. Nurses are the usual and the first responders when an emergency occurs in the hospital set up. The frequency, exposure and repeated performance of life saving manoeuvres like BLS make them more competent and skilful in delivering BLS.

As it is shown in multivariate analysis (Table 4) those nurses who had knowledge towards BSL are 2 times more likely to practice BLS manoeuvres than nurses who had poor knowledge. Similarly nurses’ who had previously performed BLS manoeuvres had 4.5 times more likely to perform BLS skills than those who didn’t expose previously. Participants who had experienced previous training were 3 times more likely to perform BLS as compared to those without such experience; this result is in line with Japan study.22 The possible reason could be explained as many literatures documented the undeniable importance of training on individual psychomotor skill.

It is crucial for nurses to be competent to deliver high quality basic life support, since nurses are the usual and first responders particularly in the hospital set up. Early initiation of basic life support has an impact on the life of individuals. It is believed that early initiations can double the chance of survival of one apparently dead.6 The present study showed that nurses who were previously exposed to cardiac patient practice much better than those who were not exposed. This idea is supported by cross sectional study in Athens Greece to evaluate the nurses’ and doctors’ knowledge and practice of basic life support, explained that those who had encountered more than 5 cardiac arrest the previous year, scored significantly better19

Despite the overall practice gap they had, 36.3% of nurses labelled themselves as confident in their ability to perform BLS. This finding is lower than study carried out in Bahrain (75.6%).16 The possible explanation for this difference might be due to the periodic certification and renewed their certification of BLS and advanced cardiac life support and the difference in sampling technique and inclusion as well as exclusion criteria. The Bahrain study used a convenience sampling technique by including only nurses who had associated degree in general nursing and excluded registered nurses.41–46

As it was found in the multivariate binary logistic regression analysis respondents who labelled themselves as confident are 7 times more likely to perform BLS as compared to those who were not confident. The possible reason for this could be due to the fact that confidence increases the competency of performing certain psychomotor skills and those individuals’ wishes to be confident in performing skills have a tendency to update their skills using different opportunities. Nurses have major responsibility in caring patients, as usual when the physician is not around, it is the nurses’ responsibility to manage patient when an emergency situation happened, therefore to accomplish this mission BLS knowledge and skill should be the fundamental role of the nurses. As it is shown in the present study knowledgeable nurses were 2 times more likely to perform BLS as compared to those with lesser or inadequate knowledge.

Majority of nurses had poor knowledge of Basic Life Support moreover most of the study participant had poor practice in delivering basic life support. Educational status, year of experience, assigned place, resuscitation training and previous exposure to cardiac arrest patient were positively associated with the knowledge of BLS. Furthermore only knowledge of nurses, resuscitation training, previous exposure to cardiac arrest and confidence in performing BLS were positively associated with the BLS practice.

MM wrote the proposal of this research; HK and ZB review the whole proposal by providing valuable comments, SA participate in the literature review and data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

We wish to extend our sincere gratitude to University of Gondar for funding. Great thanks goes to, The Chief Executive Officer of Gondar University Referral Hospital and Bahirdar Referral Hospital for allowing us to conduct this research. We also would like to thank Dr.Jennifer Kue from The Ohio State University College of Nursing for reviewing the manuscript. Our appreciation also goes to the supervisors, data facilitators and study participants. Finally we would like to thank all who involved in peer critique.

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Kelkay, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.