eISSN: 2576-4497

Research Article Volume 1 Issue 6

1Neuropsychologist, Jundia

2Psychologist, UniFieo, Brazil

3Doctor degree, UniFieo, Brazil

4Institute of geriatrician, Jundiai Medical School, Brazil

Correspondence: Juliana Francisca Cecato, Neuropsychologist, Doctor degree, Jundiai Medical School, Rua Prudente de Moraes, 111 - 13201-004 Jundiai SP, Brazil

Received: October 16, 2017 | Published: November 9, 2017

Citation: Cecato JF, Montiel JM, Andrade MSD, et al. Meanings about death for caregivers. Hos Pal Med Int Jnl. 2017;1(6):122-125. DOI: 10.15406/hpmij.2017.01.00031

Introduction: the relationships between religion and physical health have become a topic of interest among several researchers, especially with professionals that lead with patients with terminal illness. Death encompasses diverse representations for the patients, caregivers and families.

Objectives: to analyze the meanings about death in caregivers of the elderly. For this, we will present the conduct of a qualitative research through content analysis performed with women who attended a training course in caregivers of the elderly.

Materials and Methods: The IRAMUTEQ (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires) software was used with the Descending Hierarchical Classification (DHC) methodology. We will address the significance of death, as well as its relation to suffering and coping strategies for the emotional aspects.

Conclusion: The meaning of death is present at the moment of insight of the end of its own existence and to relieve the negative feelings the subject beliefs in the continuation of life (spirituality).

Keywords: palliative care, spirituality, critical illness, age

IRAMUTEQ, interface de R pour les analyses multidimensionnelles de textes et de questionnaires; DHC, descending hierarchical classification

Currently, new procedures for intervention and treatment of several types of diseases have been discussed where the search for technologies and trained health professionals is in the service of better care for patients.1-3 Regard terminal diseases care can focus on pain relief minimizing the suffering of both, patient and family.1,4 Studies have presented relevant debates about the impact of spirituality (and prayers) on the physical health. These studies indicate that more than 90% in contries like Brazil believe in a superior deity,5-7 it is being possible to verify the consequences of religiosity in mental health.8

Guimarães et al.4 in a study review described scientific evidence on the spirituality and religiosity influence on health’s patients. Naghi et al.9 also performed a review pointed out in cases of chronic and incurable diseases; it is common for patients to seek alternative methods as a complement to clinical treatment. Evidence may suggest that spirituality seems to be related to the ability to cope with an incurable disease condition. Based on these studies, Naghi et al.9 emphasizes that spirituality has a beneficial action on the quality of life of the patient, who present improvement even in depressive pictures.

Terminal diseases become the target of research with alternative interventions. In a study conducted by Travado et al.10 studied 323 patients who were diagnosed with cancer and found that 79.3% reported being supported primarily by their spiritual beliefs and faith. The authors also found statistically significant differences between the group that believed in spirituality and the participants in the group who reported having no faith (p<0.01). One factor of importance reported by the authors was spirituality being viewed as a protection against the negative feelings.

In this context, the relationship between religion and physical health has become a topic of interest among several researchers.1,4,8,10 Spirituality and religiosity are not synonymous.2,11,12 Spirituality can be considered as part of an individual's attitude, whether in the search for meanings or in thoughts that can strengthen the confrontation of sufferings. Religiousness involves the systematization of cults and doctrines shared by a group.11,13 Thus, this study aimed to analyze the meanings about death in caregivers of the elderly with critical illness.

It was decided as methodological procedure an explanatory study of qualitative approach on the meaning of death through the dynamic narrative, that is, participants could freely tell their feelings, people experiences, according to their will, nature and wealth of their emotions.

Subjects

A total of 46 women participated of content analysis, ranging age from 26 to 70 years (mean of 48.67 years). The interview was carried out in a course of caregivers of the elderly, in a city of the state of São Paulo. This city belonging to the state of São Paulo has approximately 380 thousand inhabitants. As an inclusion criterion, it was imperative to be regularly enrolled in this course and to accept to participate in the research. 30(65.22%) were married and all were literate with schooling ranging from primary (1 to 4 years) to higher education.

Instruments

A semi-structured interview was used as a basis for the beginning of the narrative. The interview was not strictly administered, only as an incentive to start the questions.

The questions were:

These guiding questions based on the theoretical reference on Death by the researchers Ligia Py et al.,1 we sought to contemplate the contents of the representations related to death, life and spirituality. The interview was conducted individually by the researchers, with approximately 40 minutes duration. The writing and later transcription of the narratives was done, constructing a discursive text, typed in the file of Writer of Open Office.

Data analyses

The processing of the narratives of the participants was done by the software “Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires” (IRAMUTEQ) version 0.7 alpha 2(2014), with the analysis by means of Descending Hierarchical Classification (DHC). This type of analysis allows the separation of the classes found in the text (called textual corpus), that is a set of words centered on a theme. The analysis through DHC allows the words of the textual corpus to be grouped from matrices intersecting parts of texts and words. Classification is done through vocabulary similar to one another and vocabulary distinct from parts of the text of other classes. From this descending hierarchical sorting division, the software calculates the data in a dendogram. The dendogram is an illustrative representation of the relationships between classes.14 IRAMUTEQ is a relatively new qualitative analysis program in Brazil which has been gaining ground in the scientific community around the world.13,15-17

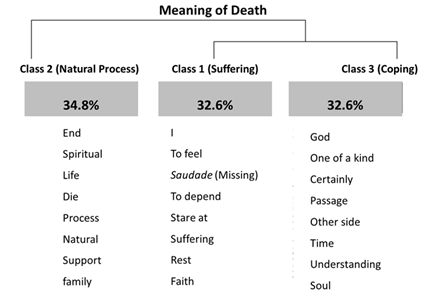

According to the Descending Hierarchical Classification (DHC) three classes were identified in the textual corpus of the analyzed material, and the result of their thematic distribution can be observed in Figure 1. Class 2 (“Natural process”) refers to the relations of the sense of life, death and spirituality, representing 34.8% of the units of elemental context of the textual corpus. Class 1 (“Suffering”) presents words in the sense of thinking about your own existence and the feeling experienced in thinking about the meaning of death. Many evocations of the word "I", "feel" and "saudade" (Saudade it is a Portuguese word that there is no translate; but it means “missing” or “missing a person that died”) were found, representing 32.6% of the corpus. Class 1 is directly related to class 3 (“Coping”), which also represents 32.6% of the words in the text. In class 3 it is possible to observe that the participants seek explanations for the meaning of death, where the words "other side", "God" and "passage" can be observed. It can be inferred that class 3 brings the elucidation of death and the comfort that these women seek to understand death not with the sense of death, but as a passage to the "other side", that is, another life.

Figure 1 Dendogram representing the thematic of the factors associated with death and the semantic division by classes and their relations.

According to DHC analysis, it was chosen to verify the relation that the classes have with each other, through the dispersion chart (Figure 2). Figure 2 shows the relationship between classes 1 and 3, with its dispersion agglomerated in the two quadrants to the right of the graph. However, class 2 presents dispersion predominantly isolated from the other classes, being observed in the two quadrants to the left of the graph. With this data it is possible to infer that the first idea narrated by the participants in thinking about the meaning of death is in relation to the end of life, being a natural process where every human being will pass. It may be seen that death, in the first instance, is distant from the self. The "I" will be represented in class 1, when the participants begin to experience the representation of their own end, since death is a natural process of life. This experience ends up bringing feelings among which it can be observed that "saudade" (“missing a person that died”) was evoked more frequently. According Brêtas et al.,18 the sense of death brings to participants feelings of pain, especially to family and friends who stay and experience all suffering after death. Among the feelings that embrace suffering are the feelings of pain, longing and incorformism. For the authors, the homesickness in this sense was interpreted as suffering by the loss. The approach described by the authors can justify the relationship between class 1 and 3, such as class 1 can be interpreted as the meaning of death as a suffering process and to deal with all pain and longing participants seek coping strategies for the process of death. The coping strategy can be observed in class 3, with evocations such as belief and faith in god appears as systems of comfort. Believing that life continues after the death of the body seems to bring comfort, through confrontation (class 3), to suffering (class 1).

Finally, the correlation between the classes according to the frequency of the words was performed. This analysis is called Similitude (Similarity), where meaning corresponds to the set of words organized by multiple relationships. This organization can be directed through causality, hierarchy, by equivalence of words, that is, to walk a symmetrical path relating their similarities and differences. In this sense, we observe in Figure 3 "life" in the center of relations and also linked to "death", representing the natural process, described in the narrative of the participants. This method allows to verify the idea that the corresponding elements of the meaning of death presents a non-transitive symmetrical relation, in other words it represents the similarity, where the designation of two words ("life" and "death") is associated within that representation. Through similarity one can verify the relationship between "God" and "Faith", being presented in a symmetrical way with "life", "passing" and "dying". Larson & Koening,19,20 in their study of belief in a deity, found that 95% of their respondents believed in a higher self. Religiousness is a practice of a group, who believe in the same ideologies and come together to practice that belief. Religion and spirituality are not synonyms, but both constructs help decrease stress and suffering caused by death.21 Just as the faith contributes to the psychic suffering that the imminent presence of death brings both to the patient and to family and friends who accompany this suffering.22,23 This fact is in agreement with the results of this research, such as there is great frequency of the words "Spirituality" and "God" in class 3. Ladd & Spilka, Nussbaum & Pulchalsk et al.24-26 sustain that the expression of suffering through belief in a higher self generates emotional relief and, at the same time, is a source of hope. According to the authors, prayer contributes to the understanding of death, being able to promote meaning for this natural process.

The qualitative approach of data analysis is a technique supported in the analysis of discourse content and, in this research, allowed to approach the meaning about death. The results point to the representation of the meaning of death and that is directly related to the associated psychological confrontation, among other words, it can be inferred that in order to face the pain of loss the participants seek to believe that death means passage to a new life without suffering. This hypothesis is corroborated with other current research.1,7,10,22

Death is a natural process of life and is closely related to the pursuit of its meaning. One word that appeared in the participants' reports was the word "spiritual" or "spirituality." Spirituality is the way man comes into contact with thought, where I come from and where we are going, an age-old practice that is now gaining ground in the scientific field.27 According to Boff27 the understanding of the meaning of life is based on a theoretical triad: matter (body), consciousness (mind/thought) and spirit (soul). Another point observed in this research was with classes 2(Natural process) and 1(Suffering). These classes are not directly related but have significant correlations. Class 2 approaches death as if it were far from happening. From the moment that the participants perceive (self-perception) that death is a natural process that is part of life, there is an insight, in other words the participants perceive that it can happen with their own lives and with that of people with great bond.7,22,28 Negative feelings are linked to the theme of death. Generally, negative feelings appear in suffering, in physical and psychic pain, and at that moment spirituality is remembered as a coping strategy for this suffering22,23 corroborates with the findings of this research, where coping strategies (class 3) are found to address the negative feelings that cause suffering (class 1). In other words, participants when they perceive the death of their own existence find strategies in their religious and spiritual beliefs to cherish the thoughts of death and find meaning for the continuation of life after the death of the body. It is known that spirituality is efficient to improve the well-being of this suffering with the understanding that death brings.29-31 It can be concluded, through qualitative analysis of data, that the meaning of death is present at the moment of insight of the end of its own existence and at the same time, as a way to relieve the negative feelings that encompass this theme, thoughts that lessen the suffering of these negative feelings the subjects beliefs in the continuation of life (spirituality).

None.

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

©2017 Cecato, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.