eISSN: 2469-2794

Research Article Volume 8 Issue 4

Department of Economics, American University of Dubai, UAE

Correspondence: Mr Alexander Schubert, Department of Economics, American University of Dubai, Dubai, Umm Suqeim 1, Segub St. Villa 131, UAE, Tel +971 50 100 5702

Received: August 08, 2020 | Published: August 24, 2020

Citation: Schubert A. What is the Optimal Level of Crime? Forensic Res Criminol Int J. 2020;8(4):156?158. DOI: 10.15406/frcij.2020.08.00321

A socially optimal level of crime is something policy makers have long thought about. To answer this question multi dimensionally, it is critical to explore “optimal” from numerous perspectives. From a purely theoretical lenses, optimality means maximizing the surplus involved in criminal acts. From a social lens, however, there are external costs and benefits that must be accounted for. The following article will further explore the ideas of crime economics, optimality, and effective policy making.

Keywords: crime, optimal, victims, economic, tax

Asking for the socially optimal level of crime seems initially a counterintuitive question. Would we not want to live in a world with no crime at all? In reality, a world with no crime at all would be economically inefficient and administratively unattainable. The idea that there is a socially efficient level of crime is no more implausible than the idea of insurances attaching a tangible monetary cost and benefit to intangible things, such as losses of life.

In the United States alone, over 8 million crimes were committed in 2017,1 costing nearly $200 billion in government expenditures- not taking into account the cost to victims.2 The point is: crime is expensive. Therefore, it is important for policy makers to answer the questions: how do we assess the tangible and intangible cost of crime? How can we balance crime prevention with increasing fiscal constraints? Which exact measures provide the highest impact per dollar spent?

The nature of the criminal market

If we are to begin to answer the question of an ‘optimal’ level of crime, it is paramount to understand the economics behind criminal behavior and how the supply and demand for criminal opportunities shape our society. The basic premise behind this theory is that crimes can be more or less profitable (in the eyes of criminals) and provided (by any member of society) as the risk of the crime changes. Demand for criminal opportunities can be explained by comparing the potential benefits for the offender to its costs. These costs include the risk of punishment, but also opportunity cost. For instance: a criminal will steal a car worth $10,000 if, in his mind, the $10,000 outweighs the risk of spending years in jail and missing out on other economic opportunities.3 As the risk of the crime increases, the potential cost increases-making the crime less attractive. Therefore, crime demand is a downward sloping curve in our crime market.

The supply of criminal opportunity is built around the premise that law-abiding individuals unknowingly supply criminal opportunities by not taking enough preventative measures. For increasing levels of risk, victims are less likely to take adequate measures, because of the increase in cost and intrusiveness. For instance, many citizens leave their house doors unlocked; some make sure their doors and windows are sealed; few go further and purchase additional security measures to meet a higher level of perceived risk. This upward sloping supply curve is a reflection of an individual's different perceived risk appetite.4

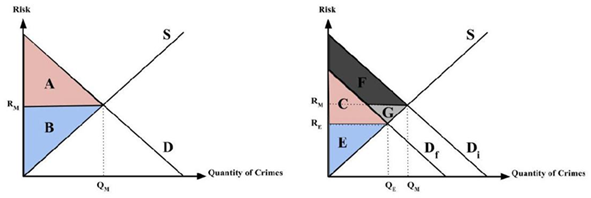

In Figure 1, supply and demand for criminal opportunities has been plotted along the dimensions of risk and quantity of crime.

Figure 1 Shows how the market of criminal opportunities changes as a result of crime prevention strategy (CPS). As a result of the demand shift, the market quantity of crime (QM) moves to an economically efficient level of crime (QE).

Exploring “economically efficient”

In the crime market, there exists both criminal and victim surplus. Criminal surplus exists due to some criminals being willing to commit a crime at higher risk levels than what the market is indicating. On the other end, there is the existence of victim surplus because some people are willing to have less preventative safety measures than what the market is indicating. In traditional product markets, surplus is a satisfactory outcome because it is healthy for producers and consumers to have excess utility. However, in the criminal market the surplus represents a deficit because it represents an unhealthy economic state that governments should want to minimize.5

How can policy makers reduce this surplus? There are two ways of doing that: policy makers can try to shift supply or demand leftward, thus reducing the area between supply and demand curve. They can do this by influencing the time and effort required to commit a crime or the actual supply of criminal opportunities by victims through certain policies. For example, as seen in Figure 1, a crime prevention strategy (CPS) can be used to cause a leftward shift of demand and reduce victim and criminal surplus.

There is no doubt that minimizing the total victim and criminal surplus through CPS can be beneficial; however, there is a caveat. Since every leftward shift of the demand or supply for criminal opportunities will be costly to governments or individuals, the marginal benefit (lost surplus) must equal the marginal cost of the CPS. This is because there will always be the incentive for governments to invest more in CPS if the marginal benefit outweighs the marginal cost. This can also be explained using our model in Figure 1. Due to the leftward shift in demand, there is a total lost surplus of G + F and a decrease in crime from QM to QE. If QE were be the economically efficient point of crime, then the additional cost of shifting Di to Df would be equal to the additional gain (lost surplus) made by the shift. Where the marginal benefit of lost surplus equals the marginal cost of additional prevention measures, the quantity of crime is economically efficient. But is the economically most efficient situation also the most socially efficient?

Exploring “socially efficient”

Social efficiency is defined as the “optimal distribution of resources in society taking into account all external costs/benefits.” The concept is closely related to Pareto efficiency, a point where it is impossible to make anyone better off, without making someone worse off.6 Hence, we must also consider intangible costs of crime in our approach.

How can we measure the intangible cost of crime? A 1996 study used a victim-compensation model in order to quantify intangible costs of certain crimes. The study finds that when factoring in the intangibles, the costs of crime are far more severe. The research specifically compared the size of the tangible costs versus the intangible costs. For example, the ratio of tangible to intangible costs for murder is approximately 1:1.85. For burglary, it is 1:0.3 (tangible costs outweigh intangible costs). For crimes such as rape and sexual assault, this figure is nearly 1:16 and - on average - over 62 times more costly in comparison to burglary. For clarity, tangible costs include short term costs that are directly associated with the crime. This can mean medical bills, victim assistance, or lost earnings. Intangible costs are long term lifestyle costs associated with the crime. This may include the pain, suffering, psychological impact, or quality of life, which was estimated at $450 billion in 1993 U.S.7

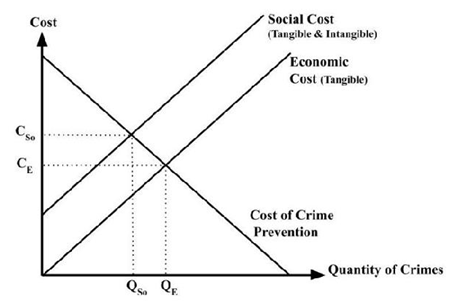

The considerable intangible costs of crime must be factored into our framework in order to fully consider societal efficiency. This shift of cost is shown in our second model, Figure 2, where the cost of crime prevention and cost to society is plotted. The societal cost curve features two curves one of purely tangible costs, and one with tangible and intangible costs. In doing this, we find that the socially optimal level of crime is at QSo shown in our third model.

Figure 2 Shows a market where cost of CPS and economic/social costs are plotted on the dimensions of cost and quantity of crimes. The model illustrates how intangible costs shift the cost curve from economically optimal to socially optimal quantity of crime moving from QE to QSo and cost of crime prevention moving from CE to CSo.

Another question poses itself while examining the demand curve of crime prevention: how can policy makers choose the most cost efficient portfolio of interventions and consequently reduce the cost of additional prevention? This necessitates us to further understand CPS.

Implementing crime prevention strategies

For crime to take place, three elements must simultaneously materialize: a motivated offender, a suitable target and the absence of a capable guardian.8 Hence, policy makers must be addressing one, if not all, of these elements. According to the Australian Institute of Criminology, crimes can generally be prevented by: increasing the required effort to offend, increasing the risk associated with committing the crime, and reducing background factors that motivate criminal thoughts.

Let’s explore some examples. Firstly, improving urban planning and design can be a massive factor in increasing both the effort to commit a crime, and the risk of being detected for the crime. Urban planners have been factoring CPS in their work for years now, with the aim to make communities more open, transparent, and bright, reducing the ability for criminals to hide.9

Secondly, CPS can consist of developmental crime prevention initiatives. The premise is that when people productively engage with you during key developmental phases, society benefits in the long run. With this initiative, important figures in one’s life such as parents, teachers, and counselors have huge roles to identify possible psychological risk factors and address them from an early age.10

Thirdly, an effective CPS could mean imposing stricter rules and protocols for certain communities. This could mean strengthening door locks, or implementing more security surveillance cameras. This would increase both the risk of being detected and the supply of criminal opportunities, leading to lesser total surplus.8

How behavioral economics can inform public policy

Though many would think of CPS as being costly and problematic, modern economists and criminologists tend to agree that there are simpler ways for policy makers to control the criminal market and cost of CPS.11 By using behavioral economics theory, “nudging” strategies can be used to significantly influence the decisions of others. These types of policy interventions are both “bureaucratically feasible and inexpensive,” which is why they are important topics of discussion.12,13

Behavioral nudging is the concept of covertly encouraging certain “consumer” choices.14 When it comes to influencing the supply of crime, there has been significant evidence that using nudging strategies to inform suppliers of criminal opportunities goes a long way. One observational study, led by Sidebottom et al.,15 measured how well people responded to such nudges. The study began by placing stickers with instructions of how to lock a bicycle around bicycle racks in London. The researchers measured people’s ability to respond and improve their ability to secure their bicycle so that no thief could steal it. The study found that, by making citizens pause for a moment and think more carefully about certain actions and consequences, there was a significant improvement in locking abilities, and hence the supply for crime.

On the demand side, behavioral nudging can be effectively used to deter criminals (or potential criminals) from committing a crime. One way to do that is through “visceral nudges”.12 There is strong evidence that suggests that emotions play a big factor in how we act in our day to day lives. By instilling a certain emotion in people, we can expect them to act a certain way. For instance, one study found that by hiring actors to stand around downtown Philadelphia in anti-littering costumes, people felt a subconscious nudge and actually littered less than before. The study concluded that negative reinforcement associated with an act is enough to deter people from committing it.16

Putting it all together

For too long, most countries have approached preventing and punishing crime from the sole perspective of public security and criminal laws. It is time for a paradigm shift complementing this perspective with a distinctive economic approach. Imagine a world in which policy makers would adopt the suggested approach of making rational tradeoffs between victim and offender surplus, economic and social cost of crime. We would likely see the focus of crime prevention strategy shift towards taking into account more of the intangible costs. This has implications of how budgets ought to be allocated and police resources ought to be deployed. It would also open pathways to a debate about the most cost effective specific crime prevention measures, which is of particular relevance in these current days of fiscal constraints.

As the most recent protests against police violence and racism in the US have shown, deploying effective CPS is more important than ever as different communities are calling for abolishing the police. It would allow policy makers to create true win-win situations between the need to prevent criminal activity and serve the legitimate desire of the population for a safe environment, while not incurring excessive cost costs that ultimately law abiding tax payers have to cover through their tax dollars.

None.

The author declares there are no conflicts of interest.

©2020 Schubert. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.