eISSN: 2469-2794

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 3

1School of Psychology, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico

2School of Psychology, University of Salamanca, Mexico

Correspondence: Ampudia Rueda Amada, Division of Graduate Studies Faculty of Psychology, Autonomous University of Mexico, Street Line 59 Numer, Colonia Hidalgo Miguél Tlalpan, Postal Code 14250, Mexico, Tel (00) 55-1-5555039721

Received: June 20, 2018 | Published: June 20, 2018

Citation: Amada AR, Guadalupe SC, Gómez FJ. Mmpi-2 based psychological profile of Mexican inmates. Forensic Res Criminol Int J. 2018;6(3):214-223. DOI: 10.15406/frcij.2018.06.00209

This study aims to obtain a psychological profile of Mexican inmates based on the administration of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2) and to obtain the main characteristics defining their personality. A total of 2,051 Mexican inmates participated, 853 of whom are inmates of different jails in the Federal District and the State of Mexico. Their results were compared with those of 1.198 non-inmate participants to discern differences. Final results show specific personality characteristics of inmates, with a prominent elevation on Psychopathic Deviate (Pd), Paranoia (Pa), Social Introversion (Si) and Depression (D). This psychological profile helps to complete data already obtained from social and demographic profiles of Mexican inmates as identified by different surveys published by the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics (Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, CIDE).

Keywords: Mexican inmates, MMPI-2, psychological profiling, delinquency

To be able to understand problems faced in Mexico’s prisons, some data must be taken into account. Statistical data collected by the Secretariat of the Interior (January, 2013) show that there are 420 correctional facilities with a total of 242,754 inmates. These facilities are designed to house 195,278 inmates, so this indicates that capacity is up to 124.3%, with overcrowding in 220 of the 420 total correctional facilities. 95% of inmates are male and 5% female. In fact, the penal system has abused convictions (96.4%) by setting jail time as sentence enforcement with imprisonment. Only for 3.6% of criminal punishments did alternative punishments were considered, such as fines and compensations.1 Overcrowding is causing, in turn, many other issues: organized gangs, failure to control prisons, ungovernability, lack of basic amenities, misclassification of inmates, poor integration of employees’ responsibilities, and, naturally, the lack of real opportunities for access to means guaranteeing effective social reintegration. This overcrowding in correctional facilities has been repeatedly denounced by many representatives of the National Human Rights Commission,2 who have expressed the need for a comprehensive solution and different strategies, policies, programs, and interventions by the branches of government to attend to this issue.3

Another underlying issue, in spite of efforts made by the existing legislation, is the high rates of recidivism: “achieving social reintegration of convicted offenders and ensuring that they do not recidivate” (Article 18 of the Constitution). The rehabilitation principle considers inmates and State as collaborators in a process designed to improve inmates’ mental health.4 Consequently, this concept has evolved to mean readjustment, and reintegration since 2008, as currently referred to as in Article 18 of the Constitution. There has been an alarming rise in the re-offender population, with a 17% growth between 2005 and 2009.5 Statistics by the Deputy Secretary of the Correctional System (Subsecretaría del Sistema Penitenciario, SSP) indicate that currently (2016) “4 out of 10 inmates who are released from prisons in Mexico City recidivate.” A newspaper report6 stated that “There are presently 36,501 inmates in the 13 correctional facilities in Mexico City, 14,158 out of which are re-offenders, amounting to up to 38.78%.” Solís et al.,1 not only do corroborate the high percentage of preventive custody, and its related contribution to overcrowding, but they also denounce that living conditions inside correctional facilities create criminogenic conditions instead of enabling the social reintegration of convicted offenders (p. 5).

Like in many other countries, Mexico’s prison population is mainly male. There are only 10,704 female inmates, who amount to up to 4.6% of the total prison population. This may be causing normative and structural configurations for prison modeling based on male characteristics and needs.7 Most correctional facilities in Mexico are built for a male population, and preparing some of them to house women implies associated “inconveniences” (such as gynecological medical services, mother-child live-in settings, kitchens and appropriate bathrooms). The essential functions of the correctional administration are based on community protection and service. Community protection is reinforced by the incarceration of charged or convicted individuals, and community service by the social reintegration of inmates once they are released from correctional facilities. Efforts have been made by the correctional administration and the Mexican Secretariat of Public Security (Secretaría de Seguridad Pública, SSP) to renew the correctional model (Estrategia penitenciaria 2008-2012) by setting forth a program fundamentally built on five pillars, the first one of which is highlighted: “An objective reception and classification system for inmates subject to prosecution, with relevant weighting for an objective evaluation of abilities and needs that contribute to individually progressive treatment planning.”

For over a decade, researchers have been continuously interested and concerned about inmates’ situation in Mexican prisons. Data from different surveys by Azaola and Bergman5,8, Bergman9,10, Pérez & Azaola11 (published by the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics (Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, CIDE)), Ampudia12 and another one published by the Secretariat of the Interior13 on the correctional conditions in which Mexican inmates live and their recidivism, have helped to bring to light the care and services provided by the correctional administration, as well as the restrictions and lack of resources that inmates face in prisons. The concept of "criminal" has not been deliberately applied to this study, primarily because Mexican correctional facilities have a mix of both convicted inmates and inmates awaiting trial (“Two out of five inmates have not been convicted,” Secretariat of the Interior14). Llamas15 provides more accurate data: 56.3% of total inmates are convicted, while 43.7% are in custody; that is, more than 100,000 inmates are awaiting trial and some of them might be discharged.

This study constitutes a contribution to the development of a psychological profile of Mexican prison inmates, as reported by the administration of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2). From a personification perspective of inmates, Psychology addresses and evaluates them as individuals, to be able to identify their personal attributes, feelings, attitudes, and likelihood to rehabilitation and community reintegration. A profile is a short, subtle, and overall representation of that which is fundamental and characterizes a figure, individual, or job position, obtained in order to have a baseline to be used for specific purposes (criminal profiling by the Police, profiling for a specific job position, etc.). This profile is to be completed, for it is only an outline of the final figure. Different profile types foster a principle of diagnostic evaluation on fundamental characteristics describing involved individuals’ abilities, customs, habits, behaviors, specific attributes, and attitudes.

A profiler’s investigation task is based on a very simple premise: every human being has a predictable behavior in the face of specific circumstances; we all have a unique, distinctive way of being (like our DNA). Personality is a way of being, expressed through an individual’s behavior, which is relatively stable and enduring, that allows cognitive and emotional aspects, interests, attitudes originated from or modeled by learning, experience, or events live through to be inferred and certain behavior across other environments and many situations to be foreseen. Our personalities or ways of being reveal themselves essentially always in the same way across different life circumstances. “If I know what a person is like, and how a person acts, I can know how this person might behave in future situations.” A profiler is not a mythological or phantasmagoric character who draws conclusions based on mystical or unreal hunches, or a sort of dark, disturbing clairvoyant or visionary, or a sort of mad Psychologist or Psychiatrist who sees what everyone else fails to see, the one who just by entering a crime scene “feels” what has happened. An offender profiler actually uses science that is pushing the boundaries of modern law enforcement, which includes analyzing murders down to the last detail, with highly scientific accuracy and a work team of investigation. In the prison setting, utility of profiling is wide-ranging, from the analysis of inmates’ ways of acting and behaviors, likelihood of recidivism and rehabilitation, and classification for imprisonment, to reporting in prisons for many purposes (positions of responsibility, prison transfer, leaves, parole, etc.). Even in forensic settings, profiling is particularly useful,16–21 especially in helping the investigation team with alternative hypothesis formation and other lines of investigation.

One of the most remarkably effective psychological tool to better understand convicted criminals’ personalities and behaviors, both to address their mental health status and to help them restore their lives and improve their likelihood of rehabilitation, is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2), for it provides multiple empirical scales that serve as a basis for psychological assessment of offenders, particularly Psychopathic Deviate (Pd), Paranoia (Pa), Schizophrenia (Sc) and Hypomania (Ma). Since the 1940’s, this test is considered as an effective tool to assess mental health and personality in individuals involved in criminal investigations or evaluations for different correctional positions.22,23 Borum & Grisso24 conducted a survey on the use of psychological tests in criminal forensic evaluations and reported that the MMPI-2 was the most widely used personality test in criminal evaluations. 96% of psychologists who use the test completed MMPI-2 based forensic reports. Also, Megargee25–27 developed a quantitative system for the classification of adult offenders through MMPI based profiling25. With a hierarchical statistical analysis, he found ten profile clusters to classify offenders (Able, Baker, Charlie, Delta, Easy, Foxtrot, George, Howe, Item, and Jupiter) and to differentiate them based on their personality characteristics. Nevertheless, his typology has been replicated in numerous subsequent studies22 reporting different results.28–34

The MMPI/MMPI-2 has been applied to a wide range of factors in prison populations, such as personality characteristics,35 mental health assessment,36 recidivism,37 malingering among defendants with mental illness,38,39 dangerousness,40 violence of offenders,41 personality traits of murderers,42 sex offenders,43–45 and psychotherapy,46 to help institutions improve and adjust their work within prisons.

The purpose of this individual and customized psychological assessment of inmates is to provide data that helps the Correctional Administration with several tasks (such as classification, leave approval, prison transfer, positions of responsibility, therapeutic program implementation, etc.) based on a better understanding of personality characteristics of each inmate, and, ultimately, fostering social reintegration. In spite of material restrictions faced in each correctional facility, the psychological capacities of each inmate to overcome with dignity their remaining years of sentence are expected to be revealed.

Design

The design for this study is supported by statistical techniques for descriptive analysis, comparison of means, and Cohen’s47 effect size between inmates and non-inmates, and between male and female inmates, across several personality variables as measured by the MMPI-2.

Objective

The aim of this study is to identify the psychological characteristics typical to Mexican inmates, in order to provide the Correctional Administration with sufficient data that assist in the determination of appropriate rehabilitation programs and help them serve their remaining prison sentence.

Participants

The number of participants in this study, including inmates and non-inmates, was 2,051, with a mean age of 26.37 (SD = 9.173). Participants were administered the Mexican version48 of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 MMPI-2;49 to identify their personality profile. A total of 853 are inmates in different Mexican correctional facilities in Mexico City and the State of Mexico, either charged or convicted of a criminal offense. 714 out of them (83.70%) are male (mean age = 33.64, SD = 8.374), and 139 (16.30 %) are female (mean age = 32.32, SD = 7.985). Data were collected from the following correctional facilities: Reclusorio Preventivo Varonil Norte, Reclusorio Preventivo Varonil Oriente, Reclusorio Santa Martha Acatitla, Reclusorio Preventivo Varonil Sur, and Centro Varonil de Reinserción Social Santa Martha Acatitla. Male inmates are most commonly charged or convicted of drug abuse/trafficking (24.93%), homicide (16.25%), kidnapping (14.57%), battery (13.73%), and robbery (13.45%). Female inmates, by contrast, are charged or convicted of robbery (36.69%), battery (32.37%), homicide (20.06%), and drug abuse/trafficking (2.88%). Regarding the educational level, almost half of male inmates (46.92%) have completed middle high school; 27.17% of male inmates have completed high school; 16.25% of male inmates have a professional job; and only 7.10% of male inmates have completed elementary school. By contrast, 35.25% of female inmates have completed junior high school; 25.90% of female inmates have a professional job; 20.14% of female inmates have completed high school; and 17.27% of female inmates have completed elementary school. The non-inmate group is comprised by a total of 1,167 young people, most of whom are students with a high school diploma (75.00% male and 87.84% female), 688 of whom (57.43%) are male (age M = 23.23, SD = 6.686) between the age of 16-59; and 510 (42.57%) of whom are female (age M = 20.15, SD = 4.154) between the age of 17-45.

Procedure

With all due permissions obtained from the Judicature and relevant authorities in each correctional facility to conduct this study, it was possible to interview inmates in order to gather all kinds of (psychological) data that contribute to a better understanding of them and to an overall view of their therapeutic needs and rehabilitation possibilities, as well as their social and demographic data. Protocols were completed either individually or in small groups, depending on resource availability in facilities. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 version for the Mexican population was administered.48 One of the underlying problems with inmates is the credibility of self-reported data. The correctional setting itself prevents inmates from honestly providing true data, since this may have “repercussions” for them. To be able to work in this context, cutoff scores for MMPI-2 scales were established as suggested by Megargee26 to identify incomplete protocols, and random or inconsistent answers, primarily through the VRIN and TRIN validity scales, and secondarily through the F (Infrequency), L (Lie), and K (Defensiveness) scales. All protocols which met the following criteria were excluded: Don’t know/Cannot Say (?) scores of 30 or greater, F-r T-scores≥90, Fb-r T-scores≥80, L-r T-scores≥80, and K-r T-scores≥80, VRIN-r and/or TRIN-r T-scores of 65-79 (inclusive). This meant the exclusion of almost half the protocols (40.24%) of the inmates and 17.38% of the non-inmates, thus reaching a higher degree of reliability and accuracy of MMPI-2 scores. Every protocol was assessed and statistically analyzed through T-scores, according to the Mexican version of the MMPI-2 measures.

Measure

In order to conduct the psychological profiling, the Mexican version (Lucio, Reyes-Lagunes & Scott, 1994) of Hathaway and McKinley’s Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 was administered, including the basic clinical, content and supplementary scales.

The purpose of this study was to obtain not only Mexican inmates’ personality characteristics but also to know whether male and female inmates showed differences. This section divides results into two very distinct parts: on the one hand, results on psychological differences between inmates and non-inmates are described, and on the other hand, results on differences between male and female inmates are yielded by comparison. Table 1 shows mean age and size effect (Cohen’s d) differences between inmates and non-inmates, both male and female. Firstly, 80% of variables are statistically significant across the Basic Clinical Scales for female inmates and non-inmates, between whom the size effect variable shows greater differentiations than those between male inmates and non-inmates.

Gender |

Scale |

Inmates/Non-inmates |

N |

Mean |

SD |

t |

d |

Male |

(Hs) Hypochondriasis |

Non-inmate |

688 |

47,96 |

7,376 |

-8.116* |

-0.43 |

Inmate |

715 |

51,56 |

9,167 |

||||

(D) Depression |

Non-inmate |

688 |

45,93 |

7,494 |

-11.007* |

-0.59 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

50,71 |

8,727 |

||||

(Hy) Hysteria |

Non-inmate |

688 |

48,96 |

8,202 |

-6.159* |

-0.33 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

51,94 |

9,902 |

||||

(Pd)Psychopatic |

Non-inmate |

688 |

48,17 |

8,410 |

-15.357* |

-0.82 |

|

Deviate |

Inmate |

715 |

55,77 |

10,082 |

|||

(Mf) Masculinity- |

Non-inmate |

688 |

49,35 |

9,475 |

-1.648 |

- |

|

Femininity |

Inmate |

715 |

50,17 |

9,119 |

|||

(Pa) Paranoia |

Non-inmate |

688 |

49,72 |

8,585 |

-12.587* |

-0.67 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

56,18 |

10,577 |

||||

(Pt) Psychasthenia |

Non-inmate |

688 |

49,56 |

8,463 |

-4.151* |

-0.22 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

51,48 |

8,811 |

||||

(Sc) Schizophrenia |

Non-inmate |

688 |

49,20 |

8,397 |

-5.415* |

-0.29 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

51,87 |

10,005 |

||||

(Ma) Hypomania |

Non-inmate |

688 |

53,11 |

10,155 |

4.226* |

0.23 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

50,87 |

9,670 |

||||

(Si) Social |

Non-inmate |

688 |

44,43 |

8,496 |

-11.727* |

-0.63 |

|

Introversion |

Inmate |

715 |

49,78 |

8,591 |

|||

(Hs) Hypochondriasis |

Non-inmate |

510 |

47,38 |

7,371 |

-6.143* |

-0.66 |

|

Female |

Inmate |

139 |

54,03 |

12,169 |

|||

(D) Depression |

Non-inmate |

510 |

44,82 |

7,548 |

-8.879* |

-0.96 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

54,62 |

12,395 |

||||

(Hy) Hysteria |

Non-inmate |

510 |

48,22 |

7,297 |

-6.412* |

-0.69 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

55,01 |

11,881 |

||||

(Pd)Psychopatic |

Non-inmate |

510 |

47,31 |

7,753 |

-12.474* |

-1.29 |

|

Deviate |

Inmate |

139 |

59,16 |

10,438 |

|||

(Mf) Masculinity- |

Non-inmate |

510 |

50,44 |

9,613 |

2.168 |

-- |

|

Femininity |

Inmate |

139 |

48,36 |

10,145 |

|||

(Pa) Paranoia |

Non-inmate |

510 |

47,98 |

7,854 |

-8.676* |

-0.92 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

57,15 |

11,771 |

||||

(Pt) Psychasthenia |

Non-inmate |

510 |

46,69 |

7,377 |

-8.675* |

-0.92 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

55,48 |

11,311 |

||||

(Sc) Schizophrenia |

Non-inmate |

510 |

46,10 |

7,240 |

-8.797* |

-0.94 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

55,04 |

11,369 |

||||

(Ma) Hypomania |

Non-inmate |

510 |

52,21 |

9,359 |

0.392 |

- |

|

Inmate |

139 |

51,81 |

11,266 |

||||

(Si) Social |

Non-inmate |

510 |

43,55 |

8,163 |

-9.479* |

-0.97 |

|

Introversion |

Inmate |

139 |

52,77 |

10,649 |

Table 1 Basic Clinical Scales (MMPI-2). Mean and Cohen’s "d" differences between inmates by gender

* Considered “Significant” to be p< 0.05

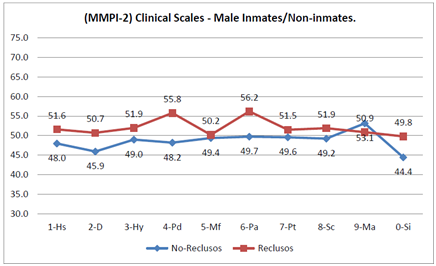

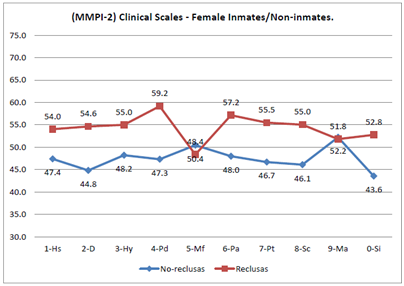

For male inmates, the four most distinctive clinical scales are, in that order: Psychopathic Deviate (Pd), Paranoia (Pa), Social Introversion (Si), and Depression (D) (Table 1) (Figure 1). These were followed by Fears (FRS), Health Concerns (HEA), Social Discomfort (SOD), Alcoholism (MAC-R), Masculine Gender Role (GM), and Dominance (Do) (Table 2) (Table 3). For female inmates, in contrast with female non-inmates, the distinctive Basic Clinical scales are Psychopathic Deviate (Pd), paranoid ideation (Pa), obsessive thoughts (Pt), and psychotic-type feelings of unreality (Sc). Another set of obtained personality attributes (Table 2) characterizing female inmates include Hysteria (Hy), Depression (D and DEP), Social Introversion (Si), Health Concerns (HEA), Anxiety (ANX), Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PK and PS), Family Problems (FAM), Social Discomfort (SOD), and substance/alcohol abuse (MAC-R).

Gender |

Scale |

Inmates/Non-inmates N |

Mean |

SD |

t |

d |

|

Male |

(ANX) Anxiety |

Non-inmate |

688 |

46,87 |

8,292 |

-5.369* |

-0.29 |

Inmate |

715 |

49,36 |

9,046 |

||||

(FRS) Fears |

Non-inmate |

688 |

47,07 |

9,181 |

-10.520* |

-0.56 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

52,51 |

10,157 |

||||

(OBS) Obsessiveness |

Non-inmate |

688 |

50,00 |

8,706 |

1.591 |

- |

|

Inmate |

715 |

49,28 |

8,058 |

||||

(DEP) Depression |

Non-inmate |

688 |

46,44 |

8,678 |

-11.565* |

-0.62 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

51,95 |

9,174 |

||||

(HEA) Health Concerns |

Non-inmate |

688 |

47,36 |

7,432 |

-9.726* |

-0.52 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

51,81 |

9,604 |

||||

(BIZ) Bizarre Mentation |

Non-inmate |

688 |

50,22 |

9,623 |

-2.619 |

- |

|

Inmate |

715 |

51,60 |

10,160 |

||||

(ANG) Anger |

Non-inmate |

688 |

48,03 |

8,163 |

0.328 |

- |

|

Inmate |

715 |

47,87 |

9,809 |

||||

(CYN) Cynicism |

Non-inmate |

688 |

46,69 |

8,644 |

-6.627* |

-0.35 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

49,86 |

9,286 |

||||

(ASP) Antisocial Practices |

Non-inmate |

688 |

45,77 |

8,700 |

-8.925* |

-0.48 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

50,40 |

10,654 |

||||

(TPA) Type A |

Non-inmate |

688 |

48,03 |

8,873 |

4.523* |

0.24 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

45,97 |

8,141 |

||||

(LSE) Low Self-esteem |

Non-inmate |

688 |

46,08 |

8,132 |

-4.961* |

-0.26 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

48,24 |

8,148 |

||||

(SOD) Social Discomfort |

Non-inmate |

688 |

44,77 |

8,834 |

-9.777* |

-0.52 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

49,31 |

8,565 |

||||

(FAM) Family Problems |

Non-inmate |

688 |

46,65 |

8,694 |

-3.615* |

-0.2 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

48,36 |

9,019 |

||||

(WRK) Work Interference |

Non-inmate |

688 |

48,09 |

8,301 |

-2.213 |

- |

|

Inmate |

715 |

49,05 |

8,039 |

||||

(TRT) Negative Treatment Non-inmate |

688 |

46,51 |

8,395 |

-6.502* |

-0.35 |

||

Indicators |

Inmate |

715 |

49,49 |

8,801 |

|||

(ANX) Anxiety |

Non-inmate |

510 |

44,61 |

7,391 |

-9.287* |

-0.99 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

54,28 |

11,661 |

||||

(FRS) Fears |

Non-inmate |

510 |

44,93 |

8,093 |

-7.468* |

-0.7 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

51,29 |

9,112 |

||||

(OBS) Obsessiveness |

Non-inmate |

510 |

47,25 |

8,362 |

-4.546* |

-0.46 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

51,42 |

9,910 |

||||

(DEP) Depression |

Non-inmate |

510 |

44,01 |

8,052 |

-11.010* |

-1.17 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

56,04 |

12,168 |

||||

(HEA) Health Concerns |

Non-inmate |

510 |

45,56 |

7,811 |

-9.177* |

-0.97 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

55,11 |

11,568 |

||||

(BIZ) Bizarre Mentation |

Non-inmate |

510 |

47,71 |

8,846 |

-4.396* |

-0.43 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

51,67 |

9,568 |

||||

(ANG) Anger |

Non-inmate |

510 |

46,42 |

7,785 |

-5.288* |

-0.56 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

51,88 |

11,482 |

||||

Female |

(CYN) Cynicism |

Non-inmate |

510 |

45,60 |

7,378 |

-6.637* |

-0.66 |

Inmate |

139 |

50,87 |

8,533 |

||||

(ASP) Antisocial Practices |

Non-inmate |

510 |

44,52 |

7,717 |

-7.832* |

-0.8 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

51,58 |

9,828 |

||||

(TPA) Type A |

Non-inmate |

510 |

46,66 |

8,235 |

-2.211 |

- |

|

Inmate |

139 |

48,63 |

9,567 |

||||

(LSE) Low Self-esteem |

Non-inmate |

510 |

43,86 |

7,767 |

-7.429* |

-0.78 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

51,35 |

11,157 |

||||

(SOD) Social Discomfort |

Non-inmate |

510 |

44,07 |

8,271 |

-8.598* |

-0.87 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

52,26 |

10,368 |

||||

(FAM) Family Problems |

Non-inmate |

510 |

43,68 |

7,799 |

-8.598* |

-0.91 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

52,58 |

11,500 |

||||

(WRK) Work Interference |

Non-inmate |

510 |

44,90 |

7,937 |

-8.792* |

-0.92 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

53,99 |

11,474 |

||||

(TRT) Negative Treatment Non-inmate |

510 |

43,97 |

8,018 |

-9.273* |

-0.93 |

||

Indicators |

Inmate |

139 |

52,22 |

9,614 |

|||

Table 2 (MMPI-2) Content Scales. Mean and Cohen’s "d" differences between inmates and non-inmates

* Considered “Significant” to be p< 0.05

However, when comparing male inmates with female inmates, differences are significantly reduced, however present, and no statistically significant differences were found using Cohen’s d. Obtained results indicate that male and female inmates differ. Female inmates tend to become more depressed (D), are more likely to have feelings of unreality with psychotic tendencies, manifest more anxiety (NX, PK and PS) and fears (FRS), and greater social (SOD) and family (FAM) problems, and have a much lower self-esteem (LSE) than male inmates. However, both female and male inmates showed a prominent elevation on Psychopathic Deviate (Pd), paranoid ideation (Pa), drug/substance abuse (MAC-R), and Social Introversion (Si).

Gender |

Scale |

Inmates/Non-inmates N |

Mean |

SD |

t |

D |

|

Male |

(A) Anxiety |

Non-inmate |

688 |

47,65 |

8,068 |

-4.445* |

-0.24 |

Inmate |

715 |

49,59 |

8,285 |

||||

(R) Repression |

Non-inmate |

688 |

49,68 |

9,152 |

-5.505* |

-0.29 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

52,43 |

9,562 |

||||

(Es) Ego-Strength |

Non-inmate |

688 |

51,62 |

7,715 |

12.715* |

0.68 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

45,94 |

8,992 |

||||

(MAC-R) Alcoholism - |

Non-inmate |

688 |

48,71 |

9,442 |

-10.904* |

-0.58 |

|

MacAndrew |

Inmate |

715 |

54,78 |

11,354 |

|||

(O-H) Overcontrolled |

Non-inmate |

688 |

52,05 |

9,548 |

-5.403* |

-0.29 |

|

Hostility |

Inmate |

715 |

54,80 |

9,505 |

|||

(Do) Dominance |

Non-inmate |

688 |

52,18 |

9,939 |

9.972* |

0.53 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

46,82 |

10,185 |

||||

(Re) Social Responsibility |

Non-inmate |

688 |

51,55 |

9,970 |

5.572* |

0.3 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

48,43 |

10,957 |

||||

(Mt) College |

Non-inmate |

688 |

46,65 |

8,350 |

-4.252* |

-0.23 |

|

Maladjustment |

Inmate |

715 |

48,56 |

8,503 |

|||

(GM) Masculine Sex Role |

Non-inmate |

688 |

71,84 |

22,488 |

27.263* |

1.46 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

46,22 |

10,291 |

||||

(GF) Feminine Sex Role |

Non-inmate |

688 |

50,50 |

8,522 |

5.561* |

0.3 |

|

Inmate |

715 |

47,69 |

10,360 |

||||

(PK) Post-traumatic Stress |

Non-inmate |

688 |

47,59 |

8,423 |

-6.543* |

-0.35 |

|

Disorder - Keane |

Inmate |

715 |

50,75 |

9,634 |

|||

(PS) Post-traumatic Stress |

Non-inmate |

688 |

47,70 |

8,581 |

-3.909* |

-0.21 |

|

Disorder - Schlenger |

Inmate |

715 |

49,51 |

8,746 |

|||

(A) Anxiety |

Non-inmate |

510 |

43,69 |

7,514 |

-8.860* |

-0.93 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

52,30 |

10,765 |

||||

(R) Repression |

Non-inmate |

510 |

50,43 |

8,562 |

-2.499 |

- |

|

Inmate |

139 |

52,86 |

10,550 |

||||

(Es) Ego-Strength |

Non-inmate |

510 |

54,18 |

7,687 |

10.129* |

1.05 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

44,66 |

10,327 |

||||

(MAC-R) Alcoholism - |

Non-inmate |

510 |

47,11 |

8,246 |

-7.078* |

-0.75 |

|

MacAndrew |

Inmate |

139 |

55,02 |

12,460 |

|||

(O-H) Overcontrolled |

Non-inmate |

510 |

53,84 |

8,679 |

2.402 |

- |

|

Hostility |

Inmate |

139 |

51,71 |

9,432 |

|||

(Do) Dominance |

Non-inmate |

510 |

79,51 |

15,463 |

30.745* |

-2.58 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

45,78 |

10,110 |

||||

(Re) Social Responsibility |

Non-inmate |

510 |

51,95 |

8,947 |

5.871* |

0.6 |

|

Female |

Inmate |

139 |

45,88 |

11,267 |

|||

(Mt) College |

Non-inmate |

510 |

42,76 |

7,928 |

-10.322* |

-1.1 |

|

Maladjustment |

Inmate |

139 |

54,19 |

12,376 |

|||

(GM) Masculine Sex Role |

Non-inmate |

510 |

55,73 |

9,756 |

9.122* |

0.87 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

47,24 |

9,722 |

||||

(GF) Feminine Sex Role |

Non-inmate |

510 |

51,81 |

8,820 |

6.388* |

0.66 |

|

Inmate |

139 |

44,78 |

12,113 |

||||

(PK) Post-traumatic Stress |

Non-inmate |

510 |

44,03 |

7,859 |

-10.870* |

-1.13 |

|

Disorder - Keane |

Inmate |

139 |

54,82 |

10,966 |

|||

(PS) Post-traumatic Stress |

Non-inmate |

510 |

43,88 |

7,766 |

-10.291* |

-1.09 |

|

Disorder - Schlenger |

Inmate |

139 |

54,66 |

11,665 |

|||

Table 3 (MMPI-2) Supplementary Scales. Mean and Cohen’s "d" differences between inmates and non-inmates

*Differences were considered “significant” to be p< 0.05

This study is an attempt to obtain Mexican inmates’ main personality characteristics by conducting a psychological analysis, in order to assist the Correctional Administration professionals, together with other social and demographic databases (CIDE), in the determination and development of appropriate therapeutic and rehabilitation programs for inmates. Utilizing the psychological variables assessed by the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2, this study has demonstrated that male and female inmates greatly differ in personality characteristics. Results were verified by analyzing more than 40 personality and credibility variables across multiple scales: Validity (6), Basic Clinical (10), Content (15), and Supplementary (15). Data obtained by this study underpins two major conclusions:

Psychological characteristics profile for male inmates

It is worth noting that to obtain and establish a profile of inmates, a comparative analysis involving young Mexican participants who are not incarcerated (non-inmates) was conducted. For known reasons, profiling in this study is gender-based. The male group inmate profile is characterized by the following personality characteristics (in order of prominence):

Those are the four essential characteristics identifying the main characteristics of Mexican inmates. As shown in Figure 1, variables with higher scores are identified with the MMPI-2 code type 4-6-0-2. Overlapping of antisocial behavior (Pd) and paranoid ideation (Pa) make inmates especially dangerous. Other prominent characteristics include:

Figure 1 Psychological profile of Mexican inmates. Basic Clinical Scales. Comparison between male inmates and non-inmates.

Note. 1-Hs, Hypochondriasis; 2-D, Depression; 3-H y, Hysteria; 4-Pd, Psychopathic Deviate; 5-Mf, Masculinity/Femininity; 6- Pa, Paranoia; 7-Pt, Psychasthenia; 8-Sc, Schizophrenia; 9-Ma, Hypomania; 0-Si, Introversion.

The female inmates profile is characterized by the following personality characteristics (in order of prominence):

Those characteristics define accurately the psychological profile of Mexican female inmates. As shown in Figure 2, the MMPI-2 typifies these four variables with the greatest scores with the 4-6-7-8 code type, which means female inmates are especially dangerous when presenting overlapping of paranoid ideation and paranoid thoughts that can be fueled by unreality patterns. Other characteristics defining them include:

Figure 2 Psychological profile of Mexican female inmates. Basic Clinical Scales. Comparison between female inmates and non-inmates.

Note. 1-Hs, Hypochondriasis; 2-D, Depression; 3-H y, Hysteria; 4-Pd, Psychopathic Deviate; 5-Mf, Masculinity/Femininity; 6- Pa, Paranoia; 7-Pt, Psychasthenia; 8-Sc, Schizophrenia; 9-Ma, Hypomania; 0-Si, Introversion

Psychological profile differs between female inmates and male inmates

Overall, female inmates profile differs from male inmates. Small differences were identified (size effect through Cohen’s d)47 to be statistically significant (p<0.05):

These data indicate that inmate profile shows a prominent elevation on Pd (Psychopathic Deviant), Pa (Paranoia), Sc (Schizophrenia), and Si (Social Introversion). The Pd scale was designed to empirically detect personality problems in offender populations; the Pa scale highlights suspicion and distrustfulness problems, with beliefs or perceptions in which offenders think that they are being persecuted or monitored; and the Sc scale is also elevated in the study by Boscan et al.,50 reporting unusual thinking, chronic behavioral problems, and social problems. Nevertheless, results on the Social Introversion (Si) scale were paid special attention to, since this scale is not regularly present in studies with offenders in correctional settings.16,22,27 The MMPI-2 Social Introversion (Si) scale type indicates a serious lack of contact with others, resulting in self-absorption as a way to protect oneself from possible aggressions by others. In the correctional setting, specified by organized crime, mafias and prison gangs, by reducing or controlling contact with others, certain behaviors and personal psychological characteristics can be conditioned, such as silence, fear, contact exclusively centered on one’s own gang, mutism, feelings of suspicion and distrust combined with paranoid ideation and thoughts, which are reported to be presented by inmates participating in this study.

Dominance (Do) and Masculine Gender Role (GM) characteristics may be the result of idiosyncratic characteristics specific to Mexican society, which requires that one present certain characteristics to be considered a man. Health Concerns (HEA), which is manifested by practically every inmate, may be conditioned by the correctional setting itself, where there is drug/substance abuse, overcrowding, health insecurity, limited food, illness uncertainty, etc. This situation has been repeatedly highlighted in several surveys by the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics (CIDE). There is very limited research on the MMPI-2 based psychological profiling of offenders published in scientific magazines, even less so of the Mexican prison population. Research by Lucio and co-authors51-54 conducted with Mexican population indicates that the MMPI-2 may be successfully applied to a variety of clinical populations, including psychiatric patients.50

These few studies include one conducted by Boscan, et al.,50 with 28 university students in Tijuana, Mexico, and 28 male inmates from the state prison in Ensenada, Baja California State, Mexico, who were administered the most recent Mexican version of the MMPI-2 by Lucio et al.48 The purpose of that study was to provide more validation data for the MMPI-2 in Mexico by comparing scale performance of university students with inmates. Although that study was conducted with a relatively small sample, results are very similar to those obtained in this study, with high elevations on the Psychopathic Deviate (Pd), Paranoia (Pa), Social Discomfort (SOD), and Negative Treatment Indicators (TRT) scales. However, the offender sample was expected to score significantly higher on scales that are reflective of antisocial behavior tendencies, poor social adjustment, and criminality.50

In the early 1970’s, Megargee empirically analyzed a MMPI based offender classification system using a hierarchical statistical method for cluster analysis of profiles.25,32 Megargee classification system, with 10 neutral-named and connotation-free types, has been the focus in more than 100 studies that have demonstrated the reliability and utility in the criminal justice setting either for inmate classification, parole/probation reporting, or mental health services,26 despite dissimilar results and discussions obtained in recent studies.22 The contribution of this study is observably in relation to the prison setting in Mexican correctional facilities. Data provided by this study cannot be completely understood without the contribution of the surveys conducted by the CIDE, being also a supplementary source for understanding the social and psychological situation in which inmates live. Every study has the same purpose of assisting the rehabilitation and reinsertion of inmates to the extent provided by legal, economical, and judicial restrictions. Overcrowding might be resulting in much more problems than expected, since it notably reduces reinsertion possibilities. Overcrowding-related problems and inmate rehabilitation difficulties have been described in some way or other by many authors such as Bentham55, Solís et al.1 & Zepeda and Lecuona.56

Yet a question remains unanswered: Does overcrowding in Mexican correctional facilities really impede custom psychological services? It is necessary to end overcrowding conditions in Mexican prisons, but this will not be solved by the suggested building of new correctional centers and facilities (which will be overcrowded again after a while). Criminal laws are in need of in-depth judicial reforms that examine offending patterns, to spare convicted offenders criminogenic effects, by making imprisonment sentences exclusive to more serious crimes1 and thus imposing other types of punishments that do not involve imprisonment for minor offences,57 always with a sensible use of custody.56 Simultaneously, it is fundamental to improve and institutionalize rehabilitation programs and reinsertion techniques that include not only psychological but also educational, occupational and vocational, health (drug abuse), and supervised progressive social reinsertion programs. However, the professionalization of the administrative and technical (psychologist included) staff and prison guards must not be put aside,1 in order to contribute to profiling that assist in the development of programs oriented to appropriate skills formation that is specific to job positions within the correctional administration.58,59

Projects support program for innovation and improvement of the teaching. Research and technological innovation (PAPIME) with grant number (Project No. PE304716. PAPIME It is a department of our institution dedicated to providing resources for research in our country and we have the authorization to publish this article. In fact it is a goal of the project.

Authors declare there is no conflict of interest in publishing the article.

©2018 Amada, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.