eISSN: 2469-2794

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 1

Department of Science and Technology, Nottingham Trent University, Clifton Lane Nottingham, United Kingdom

Correspondence: Andrew O’Hagan, Department of Science and Technology, Nottingham Trent University, Clifton Lane Nottingham NG11 8NS, United Kingdom

Received: January 26, 2018 | Published: February 7, 2018

Citation: O’Hagan A, Quinn L. Mental health a policing challenge for the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Forensic Res Criminol Int J. 2018;6(1):54-62. DOI: 10.15406/frcij.2018.06.00184

Mental health is becoming a serious problem. Statistically, one in four people in the United Kingdom experience a mental illness annually. Countries throughout Europe and indeed the World are also experiencing crisis relating to mentally ill patients. The United Kingdom and the Netherlands are two such countries. It has been noted by police forces within the Netherlands that many people experiencing a mental health problem will commit petty crime in which the police have to deal with. Within the Netherlands, an epidemiological study reveals the truths behind what the police have to deal with along with how they deal with the mentally ill. This is then used to compare to how the United Kingdom’s Police Forces deal with the mentally ill so that police in the Netherlands can deal with the crisis more efficiently and rapidly.

Keywords: self-actualize, self-esteem, wellbeing; psychoses, neuroses, neurotransmission, post synaptic, presynaptic, place of safety, oecd country, institutionalisation, mental illness

To define what constitutes mental illness is far from obvious.1 It involves our psychological, social and emotional well-being. Its effect on how a person acts, feels and the way they think can determine our relation to others, how we handle stress and the choices that we make. It is fundamental that a healthy mental state is acquired throughout life.2 The wellbeing of an individual will change in the response to the realisation of their own abilities, as well as coping with stress occurring in ‘normal life’.3 The problems an individual may face can range from a worry to a long-term condition.4 These prolonged conditions can then alter an individual’s function.2 Deviation from ‘ideal’ mental health is deeply researched. Psychologist Dr Marie Jahoda proposed the following criteria to have good mental health. This criteria is now used as a guide to distinguish deviation of mental health.5 Her guide includes some of the following criteria:

The passage between a ‘normal’ individual and an ‘abnormal’ individual is due to the response of the coping of demands, leading to failure to function competently. This crossing of the line will vary between individuals and the decision could be based on the ability to maintain standards such as hygiene or alternatively holding down a job.6 Psychologists David Rosenham’s and Martin Seligman’s research suggested signs to work out when an individual is not coping. These include:

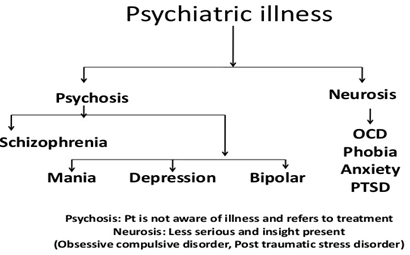

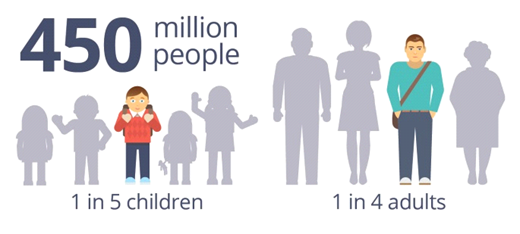

Naturally, mental illness is divided into two distinct groups; Psychoses and Neuroses, seen in Figure 1.8 Although sometimes difficult to differentiate, psychoses usually involve a distorted impression of reality and neuroses do not. Numerically psychoses are fewer and tend to be associated with more serious conditions, like schizophrenia. Neurosis is considered mellow in comparison, as well as more common,1 symptoms found tend to be extreme versions of ‘normal’ emotions, and can include conditions such as depression or obsessional behaviour.4 Mental illness affects around 450 million people worldwide8,9 and Britain usually see around a quarter of their adult population10 and a fifth of their child population suffer from a mental illness,11 illustrated in Figure 2. A mental illness is not judgmental to its sufferers and the exact cause of it is unknown. Research conducted into mental illness has found that it is most likely due to a combination of factors biologically, psychologically and environmentally.12

Figure 1 Flowchart showing psychoses and neurosis related illnesse.8

Figure 2 Infographic showing annual frequency of mental illness.11

Disorders of the brain are thought to be due to disturbances within the cognitive function and this, in turn, will cause effects emotionally affecting mood or physically affecting heart rate, appetite and the behaviour of the sufferer.13 Research has shown that mental illness is most likely caused by changes of neuro chemicals within the brain. It is to many scientists belief that neurotransmission problems occur when a person experiences a mental health problem. Disruption in levels of serotonin, dopamine, glutamate and norepinephrine can lead to depression or schizophrenia within humans. These findings are then used to specifically design medication to treat individuals with mental illness. People with depression usually experience low serotonin levels leading to reduced binding within the postsynaptic neuron. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI), decrease the amount of serotonin reuptake by the presynaptic neuron so an abundance of serotonin is in the synaptic cleft, creating an increased chance of binding with the post synaptic neuron, this would help the sufferer to feel happier.14 A visual representation of the neuron activity can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3 World Health Organisation’s life course approach.16

Diagnosis for mental illness is not a simple matter. Local doctors in general practice will focus on the symptoms experienced, the length they occurred for and the impacts upon lifestyle of the patient. Common neurosis problems will usually be diagnosed by the General Practitioner (GP) whereas psychoses will be diagnosed by a psychiatrist due to a referral from the GP, and they will refer to the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases System to find a specific diagnosis.15 Economic, social and physical environments serve to shape mental health disorders that are experienced within a section of the public. It has been noted by the World Health Organisation that social inequalities are profoundly associated with mental disorders. Actions then have to be taken in order to improve the conditions of daily life from before birth to old age to reduce the risk of mental disorders, however, action must be universal. This regards the society as a whole as well as being proportional to the need within certain social environments. Actions throughout the life stages along with the proportional need will aid in the improvement of mental health within a population.16

The World Health Organisation’s European review affirms a life–course approach seen in Figure 4, to interpret mental health inequalities due to social determents within the different stages of life.17,18 There is evidence to suggest that mental health conditions, which present in later life, do in fact originate in early years.19,20 Stress that is experienced in the ‘Early years’ stage, has been shown to affect stress regulatory systems within the brain as well as an increase in the expression of genes that are associated to a stress response.21 These in turn are buffered by the social support within a population.22 It is therefore fundamental that there is an attachment between a child and the caregiver in order to help stop increased anxiety and to assist them to cope with stress.23 If these vital responses do not occur, stress related behaviour can induce a development of addictive behaviour like alcohol and drug dependency within an individual, commonly resulting to an increase in committing crime.24

Figure 4 World Health Organisation’s life course approach.16

Police & mental health

UK police

United Kingdom police forces faced 239,388 incidents in 2016 relating to mental health. Nottinghamshire Police recorded most incidences, experiencing 19,973 and Lincolnshire with the least incidences at 2,512.25 Danny Bowman, the Mental Health Spokesman for Parliament Street suggested that the findings reveal shocking numbers of mental health issues currently being dealt with by the UK police forces.25 The UK government have invested £30million to provide alternate places of safety, as well as decreasing the amount of people detained within a police cell under the mental health section by half in 2016. Police Sergeant Anthony Horsnall identified mental health as a priority within Nottinghamshire’s Police and Crime Plan.25

Police in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, police have to deal with nuisance, public order disturbances and small crime committed by people that suffer from mental illness. This could be seen as a waste of time as many are responding to what is thought to be an emergency call when in fact many are small problems that could have been solved in a different way. Only 6.1% of total health and social care budgets are used in the Netherlands by mental health providers so there is room for improvement when considering mental health problems and how they can be dealt with.26 Economic costs to the Netherlands regarding ill mental health are large and reach 3.3% of Gross Domestic Product. This can be through state benefit systems or the costs of health care.26 The Netherlands currently witness members of the public not working due to mental health and figures are around 30-50% higher than any other OECD country. Usually in the Netherlands, these mentally ill will frequently rely on disability, social and unemployment benefit systems.26

It was found in 2012, 40% received social benefits, 30% received unemployment benefit and 7.9% of the Netherlands working age population received disability benefits. Due to the lesser chances of employment, whilst experiencing a mental health problem, this can give them more time to commit petty crime,26 in which the police have to deal with. The police in Assen, the Netherlands, continuously have to deal with calls that are about crime or nuisance being committed by people with mental health issues. In the year of 2015 t/m 30th November 2016, there were 777 call outs for the police regarding mental health, a 63% increase in numbers from 2014. Figure 5 visually represents this, from April to 6th November 2015. Call outs are mostly to do with alerts and assistance needed by people to deal with the mentally ill. The police however sometimes feel they do not have the time or resources to deal with this all of the time. Sometimes they are being called out to small instances that could have been dealt with in a different way rather than with the police. This review will include the problems faced by the police in the Netherlands due to mental health issues with a comparison to the UK policing systems. It will address a broad range of areas containing what problems they face from an epidemiological study and solutions with what can be put in place to help the Dutch Police deal with the problems.

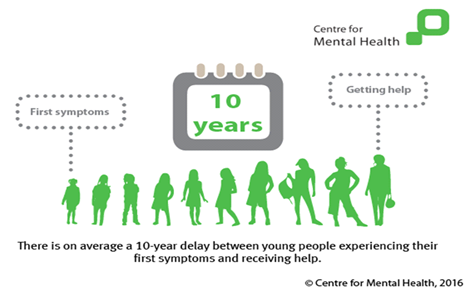

Figure 5 Infographic illustrating the time between first symptoms and receiving of help.52

Research was conducted in Assen, The Netherlands, with the use of an epidemiological study. Officers from the Dutch National Police based in Assen City Centre in the province of Drenthe answered a series of questions in order to evaluate how people with mental illnesses are treated by the police in a situation of distress or when crime is involved The questions involved the call outs the police attend regarding mentally ill individuals and what happens if the police believe they are in distress. It also includes, where they take them to be analysed by a doctor. It involved checking upon the mentally ill whilst in police care and how long they stay within their care, along with information about the doctors that analyse them and the deterrence’s available to stop the committing of crime.

The police responded that the call outs they receive tend to be to do with moving a mentally ill person within a home, this is due to having to use reasonable force because under distress, many will become aggressive. The police also suggested that they have to deal with mentally ill people going missing due to abusing their freedom or just walking out of their homes. The police force has said they have to deal with crime such as alcohol or drug abuse by persons of a mentally ill nature, this is through shoplifting to fund habits. It is very rare that serious crimes are being committed frequently by mentally ill persons. Results show that when police, either arrested or escorted the person voluntarily, they had no alternative, but to convey them to the police station and place them in a cell, even if the person was severely mentally unwell. They then had no alternative but to remain with the person until a doctor diagnosed mental illness. The procedure can take in excess of 6 hours on occasions. Within the policing systems in the Netherlands, there are currently no police powers for the officers to use to deter the mentally ill committing crime repeatedly and it has been suggested that mentally ill people are treated exactly the same as any other criminal which was believed to be irrational.

Whilst conducting the research in Assen, enquiries were made with the police in the United Kingdom, in relation to policing systems utilised to deal with people with mental health issues. Comparisons were made with police forces in London Metropolitan, the North West regional policy involving Merseyside, Derbyshire, British Transport Police, Manchester, Cumbria, Lancashire and Cheshire Constabularies, as well as Nottinghamshire Police, in order to gain an insight into how the British police deal with mentally disturbed people. Research was conducted into areas opposed to those regarding custodial sentencing. The aim of a custodial sentence is to punish convicted offenders within prisons. Along with custodial sentencing come psychological effects, which in turn are not ideal for mentally vulnerable people. These effects involve:

Stress and depression

With suicide rates within prisons increasing rapidly higher than that within the general public, and the stress experienced within prison can induce disturbance after release.

Institutionalisation

Becoming so acclimatised to the routines within prison that when released they cannot cope with everyday life.

Prison

Behaviour that is considered unacceptable in the outside world may become acceptable within the prison environment, inmates will often adopt an ‘inmate code’.27 Alternate options for the mentally ill regarding police cells and prisons are vital in the help in recovery of the sufferer. Clinical studies have shown that up to 15% of people in both city jails and state prisons have very severe mental illness,28 thus providing alternate methods may induce a decline of police dealings regarding mental health and ensure that the sufferers are getting the correct help they need. People experiencing severe mental illness are often over characterised within the criminal justice system. Many believe that they are very violent, however, they are often very ill and are dealt with unfairly. Diversional programs seen below will help to increase the options available for mentally ill patients committing crimes29 in the Netherlands.

Acceptable behaviour contract: An Acceptable Behaviour Contract (ABC) is used within the United Kingdom as a written agreement between a person and the arresting officers involved in an anti-social behaviour act. The contract specifies the acts committed and it is agreed those acts are not continued, especially if they involve crime or nuisance. The individual can also be involved in drawing up the contract in order for them to recognise the impact of their behaviour. The flexibility of these ABC’s allows police forces to take the lead on incidences and incorporates a way of tackling unacceptable behaviour efficiently. Monitoring however, is vital to the success of an ABC and early intervention can prevent behaviour escalating. When the use of an ABC is in conjunction with a person of mental illness, practitioners with relevant knowledge are involved in the process of the assessment. This will help to determine any mediation that may need to take place. Police forces must ensure that those with mental health disabilities are not ruled out from a level of support.30

Community treatment order: Section 3 and Section 37 of the Mental Health Act 1983 state that you can be detained in hospital, and that mental health professionals are able to take you to a hospital for treatment, respectively.31 If a person has been taken to the hospital under Section 3 or Section 37 the Mental Health Act 1983, the responsible clinician can arrange for a Community Treatment Order (CTO) for the sufferer. Having a CTO means that a mentally ill person will have managed treatment when they leave hospital, and if they need to go back to hospital the clinician has the authority to readmit them. If the medical professional decides to take them back to the hospital, they can be held for 72 hours whilst the psychiatrists make an assessment. In order to stay out of the hospital, a person must follow the conditions to the CTO. These conditions make sure that the sufferer continues to get treatment, and will enable protection for that person as well as arranging where they will live or where they can access treatment. A community treatment order will continue until a responsible clinician discharges the sufferer.32

Detention places of safety: Under Section 136(1) of the Mental Health Act 1983 it states: “If a constable finds in a place to which the public have access a person who appears to him/her to be suffering from mental disorder and to be in immediate need of care or control, the constable may, if she/he thinks it necessary to do so in the interests of that person or for the protection of other persons, remove that person to a place of safety…” Under this section, mentally ill people can then be detained for a maximum of 72 hours, this is however different from arrest. This power can only be used if the four conditions are met. These are:

Section 135 of the Mental Health Act 1983 states that a police officer can take the sufferer to a place of safety from a private place and are allowed to force themselves into their house.34 A place of safety at that time will be in a 136 suite in a hospital. However, they can only be kept under this section for 72 hours. During this time, mental health professionals will arrange an assessment for the sufferer, and decide whether they need to be admitted to hospital. After being assessed, a person could be subjected to sectioning or could be free to leave. This 136 suite will be used as the detainment area for the sufferer and will be their place of safety. The only time it would be considered not to be was if the detainee:

Triage system: Police in the UK, have set up a project that commenced on the 31st March 2014 called ‘The Street Triage System’. This scheme has been put into place to allow mental health nurses to join patrols and assist officers on call outs. The system is funded by the Department of Health and is backed by the United Kingdom’s Home Office.35 It prides itself on improving the way in which police forces view mental health problems and the way they are treated during emergencies. Former Care and Support Minister Norman Lamb is backing the idea and has stated that “providing police forces with support of health professionals can give the officers the skills they need to treat vulnerable people appropriately in times of crisis and allowing police officers’ time to become more free to enable more time to fight crime.”36 Using information from London Metropolitan Police, the service comprises a band 6 experienced mental health nurse on duty 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, sometimes this can be face to face or a telephone and advice helpline.37

In the UK, Section 135 and Section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983 gives police officers the powers to take a person to a place of safety when found in a private or public place, respectively.38 They can do this if they believe that the person has a mental health illness and are in need of care. The first recorded dataset by the Metropolitan Police was in June 2014, there were a total of 87 interventions, whereby 56 could be detained under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983 due to being in a public place. Of these, 75% were continued to be detained under Section 136 in a place of care.37 Table 1 below shows the number of detentions from the Metropolitan Police under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983 from April 2012 to August 2014 and whether a person was taken to a place of safety or kept in custody.

|

Date |

Section 136 |

Custody |

Place of Safety |

Not Stated |

|

12-Apr |

69 |

1 |

64 |

4 |

|

12-May |

90 |

1 |

84 |

5 |

|

12-Jun |

105 |

0 |

95 |

10 |

|

12-Jul |

81 |

0 |

75 |

6 |

|

12-Aug |

97 |

0 |

88 |

9 |

|

12-Sep |

93 |

1 |

85 |

7 |

|

12-Oct |

89 |

0 |

82 |

7 |

|

12-Nov |

93 |

0 |

88 |

5 |

|

12-Dec |

106 |

1 |

94 |

11 |

|

13-Jan |

66 |

0 |

66 |

0 |

|

13-Feb |

77 |

0 |

76 |

1 |

|

13-Mar |

83 |

1 |

81 |

1 |

|

13-Apr |

92 |

0 |

91 |

1 |

|

13-May |

110 |

0 |

109 |

1 |

|

13-Jun |

135 |

2 |

126 |

7 |

|

13-Jul |

128 |

0 |

124 |

4 |

|

13-Aug |

118 |

2 |

114 |

2 |

|

13-Sep |

114 |

0 |

114 |

0 |

|

13-Oct |

141 |

3 |

133 |

5 |

|

13-Nov |

108 |

0 |

106 |

2 |

|

13-Dec |

124 |

2 |

120 |

2 |

|

14-Jan |

138 |

1 |

137 |

0 |

|

14-Feb |

118 |

0 |

115 |

3 |

|

14-Mar |

124 |

0 |

123 |

1 |

|

14-Apr |

157 |

0 |

155 |

2 |

|

14-May |

177 |

1 |

174 |

2 |

|

14-Jun |

151 |

2 |

147 |

2 |

|

14-Jul |

150 |

2 |

143 |

5 |

|

14-Aug |

103 |

1 |

102 |

0 |

Table 1 Metropolitan police detentions under section 136 of the mental health act 1983 from April 2012 to August 201437

In the UK a new proposal has been underway since September 2012. This entitles new rights for the public who are detained under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983. These proposals suggest that people with suspected mental health issues who are detained under Section 136 have to be assessed within three hours and are not allowed to be kept in police custody for longer than 12 hours. The legal limit of 72 hours in custody does not take into account the timing of the mental health assessments for people to be detained under Section 136. The new draft therefore recommends that a police station is not to be used as a place of safety except in notable circumstances. A statutory care and treatment plan, if needed for the individual, will be completed up to 72 hours after admission to hospital.39 The United Kingdom’s Police have estimated they spend about 40% of their time dealing with people with mental health issues.40 Figures from May 2015 show that at least 21,995 people were sectioned under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983, and 20% of these were kept in police cells due to no other alternative available.41

Prime Minister Theresa May has awarded £15 million into health facilities to refrain from detainment under the Mental Health Act in a police cell rather than a place of safety and to ban children being held.41 This £15 million will be used as funding to provide alternatives for the mentally ill who are spending time in detention in police cells rather than a place of safety and to stop any use of police cells to detain any minors experiencing mental health problems.41 The ban regarding the detainment of under 18’s within police cells as ‘places of safety’ is going to affect around 150 children per year due to the absence of alternate health facilities.41 The proclamation incorporates an agreement to ensure plans of places of safety for people experiencing a crisis, with new funding available to the NHS, co-operation with the police and crime commissioners, to fund alternative places of safety.41 Theresa May expressed that when the police are sent to look after people suffering from mental health problems, “nobody wins”. This is because the “vulnerable people do not get the care they deserve or need and the police are not doing the job they are trained to do” fight crime. This £15million will enable the government to obtain places of safety in England and assure that a person with mental health problems will not be placed in a police cell due to the lack of a suitable alternative. Theresa May later went on to say that “the right place for a person suffering is a bed, not a police cell, and the right people to look after them are medically trained professionals, not police officers.”41

Helpline: The Triage System available to the UK police means that mental health nurses can assist officers and accompany them to mental health related calls. This service however is not always completed with a mental health nurse with them all of the time. Sometimes officers can use a telephone support and advice helpline. This help line can be accessed by police officers to give them support and advice on how they can deal with the situation.37

Punished/treated: There are always conflicting opinions surrounding whether it is appropriate to punish and/or treat mentally ill individuals that commit crime. Generally the population become anxious about their own safety and find it difficult to understand that a mentally ill person who commits a crime may become hospitalised and eventually discharged, rather than being punished in line with the law. Placing people in jail will always cost the government more than treatment facilities as it will increase taxpayer costs to care for them.42 Mental Health Courts could be a solution, and may be an option for the Dutch Police Force to consider. The goal of these courts is to introduce more treatment to sufferers as a substitution of jail time with the use of legal authority to ensure the plan is followed.42 Research showed that the mentally ill tend to stay in treatment longer and chances of reoffending are reduced. Serious crimes however, cannot be handled through these courts such as murder, arson or rape, for example. The growing number of mentally ill people in prison can be seen as a failure of society as there has been a failure in care. A goal would be to get them into hospital before they should have the chance to commit a crime.43

A pre-arrest assessment should be conducted by a police officer when they arrive at a scene and this should determine whether they should be arrested or taken to a place of safety. Due to the police officers not having qualifications to diagnose, the use of the triage system allows them to speak with a qualified mental health nurse to look at the severity and to decide the course of action. In the UK if someone is believed to have a mental health issue and arrested, the arresting officer has to complete a mental health form in all cases.44 A Sussex mental health patient who ended up within a police cell, experienced severe distress whilst being held within the cell. She stated that she was covering her ears whilst screaming, shouting and swearing, praying that the doctor would hurry up.45

Security nurses: Security nurses, like general nurses, will perform skilled procedures and treatments, for example taking blood pressure, administering medication, etc. However, they will also be able to perform security work like attending patient’s appointments and being able to physically and therapeutically intervene when patients display ill behaviour.46

Education: Educating people is vital to understanding mental health. Whether it is in the schooling systems or in the work place, it allows an insight into providing people with a sense of identity and dignity. Good mental state is proportional to positive educational and behavioral outcomes showing that it is a vital step. In school systems very few children receive interventions to promote mental health and how to prevent and reduce mental illness. Mental health promotion within places of learning will have positive consequences on a child’s development, including educational outcomes and honesty. Integrating mental health into policies relating to education allows development and safeguarding of society’s most compelling and least mature resource, the mental health of children.47 The ‘Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Study’ covers most EU members. It collects information on the health and nature of young people between 11-15 years, including emotional and psychological conditions. The recent study showed that between 16-27% of females and 12-16% of males rate their health and well-being as ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ and self-reported health and well-being decreased for both genders when comparing to a previous study conducted.48 Providing direction to schools will help to:

Scientific investigations into positive mental health has enabled scientists to reveal six approaches to be taught in order to promote positive mental health, these include:

Mental health is considered one of the major causes of absence within the workplace. On average it takes around 10 years from first symptoms of mental health to when a person receives help,52 illustrated in Figure 6. With the workplace being an environment that can seriously affect mental state, the promotion of good mental health is vital. Places of employment should encourage steps relating to the promotion of mental well-being, and companies have noticed a proportional link to the productivity of an employee. These five categories include:

Institutions: There are a number of institutions available in the UK that could also benefit the communities in the Netherlands. These include:

Early intervention: Research has shown that 75% of mental health disorders will start before the age of 25 and receiving help earlier will make a significant difference in recovery. As mental health issues can affect all aspects of a person’s life whether it is work, social, family or relationships, early intervention could lead to treatment starting and management of their illness. This could be beneficial in engaging with people committing crimes that have a mental illness.54 Early intervention work with a person who is experiencing psychosis for the first time. They will help to make an analysis of a person’s symptoms. After being referred by a GP or a hospital, the team of psychiatrists, community psychiatric nurses, psychologists, social and support workers will then provide a care program for the sufferer to follow or refer them for recovery at relevant places of safety.55

People in crisis: Specialised places of safety are available for the mentally ill to access beds when in crisis. NHS England has just awarded a 12 bed unit in Bodmin in Cornwall to open in the summer of 2019 for young people with mental health issues. It has been known that young people from this area to have to travel to Cheshire and Norwich for their treatment. The treatment centre will allow care closer to home and help the people in crisis at a better integration into ‘normal’ life.56

Home treatment: By obtaining a home treatment service, it enables the individual to feel that their needs are being focused on directly rather than in the care system. This increased security will allow the patient to feel comfortable and may aid in the recovery process. The service is available 24 hours, 7 days a week and planned visits from teams of nurses and psychiatrists will occur.57

Day hospitals: There is an alternative to home treatment for people who are very unwell. They provide psychotherapeutic therapy to patients along with assessment and support for the sufferer. Due to being a short-term option, this care centre can help the sufferer on a particular day and will provide support for that day or provide alternative care if needed.58

E Cards: A PCSO from Lancashire constabulary has created an ‘E Card’, an emergency information card. This is a support card for someone with a mental health problem and means when they come into contact with the police, either as a victim, witness or suspected offender it provides an option to reduce distress. It will encourage efficient communication and mean the person will get the right additional help if needed.59 The size of a credit card, it contains the person’s name, a photograph, any medical conditions, emergency contact information, and other useful information e.g. communication needs. At this given time around 10,000 people are making use of them in Lancashire.59 PCSO James Holland, the inventor of the card, from Lancashire constabulary stated “I have been told face-to-face by people with experience of mental distress that the E Card has given them more confidence that if they come into contact with the police, they will receive a more understanding, patient and equal service because they have something that they can present to police officers.”59

All of these alternate methods provide help to the police system to enable police within the United Kingdom to help create a better relationship and experience for mental health sufferers, something the Dutch police forces can learn from. It must also be taken into account the threat that is exposed with the individual. In certain cases of very serious crime e.g. murder, it may be appropriate for the safety of the individual as well as the public that a police cell is used, however keeping to the relevant checks and doctors being available within police stations will allow the time spent within the cell to rapidly decrease. This in turn will enable the experience for the sufferer to be less stressful and for them to feel more at ease. The alternate methods must however not be abused and must carefully be monitored, this will ensure that the other services are not being overcrowded and it must not be used as a way for the police to just drop them off or move the problem on.

Devon and Cornwall police forces have shown that there has been a 73% decrease in mental health patients being detained within cells from January 2015 however, this decrease has been linked to major affects for Accident & Emergency (A&E) departments in the South West of the UK.60 This tension between the police and the other services has, will and is currently creating longer waiting times meaning the mentally ill are not getting the nurturing they truly need. It is known that the police are not necessarily intentionally passing on the patients however, it is believed to be a better place for them than a police cell. It therefore has recently been announced that A&E departments will be pledged with £247 million to improve mental health services to accommodate with the new laws coming into force.60

Overall, problems with mental health in Assen are rising and with a 63% increase in 2015 of calls being sent to the police to deal with nuisance or crime committed compared to 2014, there needs to be something in place to try to control the numbers. Comparing the UK policing systems to that in the Netherlands, we can clearly see that there is a vast difference in how the police may deal with someone who has mental disturbance. Research has shown that psychological problems increase the likelihood that people will make poor behavioral choices which can contribute to medical or policing problems. Good mental health will improve some bodies quality of life and this peace of the mind is extremely important and will strengthen the ability for people to have healthy relationships, make good life choices and maintain physical health and well-being.54 Knowing that only 6.1% of total health and social care budgets are used in the Netherlands by mental health providers, the key to success will be using some of the money left over to put in preventative methods with the goal to create a decline in numbers of nuisance calls received to the police. In the UK, MP Nick Clegg, has said the sector needs a ‘breakthrough comparable to penicillin’61 and in 2015 saw that mental health services in England received £1.25 billion in their budgets, with the money being spent over five years mainly helping young people with mental health issues.62 It is clear that the Netherlands would benefit from further research and closer liaising with the authorities in the United Kingdom. This will help their understanding of this ever-growing problem and could develop their response in relation to mental health.

None.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 O’Hagan, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.