eISSN: 2469-2794

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 1

School of Psychology and Therapeutic Studies, University of South Wales, UK

Correspondence: Sandra Taylor, School of Psychology and Therapeutic Studies, University of South Wales, Pontypridd, Wales, CF37 1DL, UK

Received: February 04, 2018 | Published: February 16, 2018

Citation: Taylor S, Lui YL, Workman L. Defendant’s mens rea or attractiveness: which influences mock juror decisions? Forensic Res Criminol Int J. 2018;6(1):64-70. DOI: 10.15406/frcij.2018.06.00185

Mock juror studies have been used to help elucidate our understanding of how people come to make decisions concerning the extent of guilt of an accused. One area of debate concerns the relative merits of evidential and non-evidential information in this decision making process. In the current study, 155 (79 males, 74 females) participants read one of three versions of a fictitious transcript of a theft/handling court case, varying in the defendant’s intent only (but indirectly addressing differences of motive). A photograph of the defendant, attractive or unattractive, was attached to each transcript. ‘Mock jurors’ made decisions of extent of guilt, sentence and probability of intent. Results indicate a significant difference for the variable of intent for extent of guilt (F(2,135)=3.799, p<0.05), sentence (F(2,135)=7.438, p<0.001) and probability of intent (F(2,135)=4.993, p<0.01). No attractive-leniency effect was found for extent of guilt (F(1,135)=0.069, p>0.05), sentence (F(1,135)=0.107, p>0.05) and probability of intent (F(1,135)=0.377, p>0.05). Equally no sex of juror difference was found for extent of guilt (F(1,135)=0.001, p>0.05), sentence (F(1,135)=0.292, p>0.05) and probability of intent (F(1,135)=0.028, p>0.05). As intent increased, mock jurors were less lenient (ignoring the motive for the act). They appear to give the benefit of the doubt to the defendant who pleads not guilty, even when the only evidential information missing is admittance to theft/handling despite detail consistency across transcripts.

In order to improve our knowledge of how jurors come to make decisions, psychologists and criminologists have developed the ‘mock juror’ paradigm. Here the details of a mock (or real) criminal event are presented to a group of individuals acting as though they are jurors deliberating a trial. A number of mock jury studies have considered both evidential information, such as how the alleged perpetrator might be linked to the crime and non-evidential information (commonly known as ‘extra-legal defendant characteristics’), such as physical and social attractiveness, gender and ethnicity. In theory, only evidential evidence should be considered when determining the probability of guilt. Technically, in court evidence presented should be in aid of ascertaining the two defining elements of a crime, the act itself or actus reus and the underlying culpable state of mind behind the act or the mens rea. Non-evidential evidence should play no role here.1 The mock juror study paradigm enables researchers to look at the issue of mens rea as part and parcel of evidential information.

In contrast to actus rea, mens rea is not easily defined. To illustrate this, Giles2 outlined four states of mind which separately or combined can constitute the appropriate mens rea of a case. Giles points out the common error of assuming that intention and motive are one and the same by drawing upon the case of Steane (1947). During World War 2 he was accused of broadcasting information ‘with intent to assist the enemy.’ However, in reality Steane was broadcasting because of threats to his family. He was found not guilty because he had not intended to assist the enemy but rather to protect his family. In other words he was coerced into this behaviour. In law intent can be direct or oblique.2 In the case of direct intent, the consequence is desired unlike oblique intent where it is not. A defendant may not wish for a consequence of his action to occur but nevertheless continues with his action knowing that the undesired consequence is likely to be realised. Differentiating oblique intent from recklessness is more a matter of degree: that is, it depends on the defendant’s perception of consequence probability. Desiring the consequences is considered to be ‘intent’ unlike recklessness where the lack of foresight of the consequences cannot be taken as intent (The House of Lords 1990). Recklessness by law involves taking unjustified risk. This delineation is further complicated by the notion of specific and basic intent.2

For crimes of basic intent (i.e. criminal damage, manslaughter, common assault and rape) mens rea can be intention or recklessness. In the case of crimes of specific intent, direct or oblique intent is relevant (i.e. murder, theft and burglary). Negligence and blameless inadvertence are also pertinent here. Negligence is about failing to perform to the expected standards and omitting or engaging in something that most people would not do. If a person fails to realise the existence of a consequence resulting from his/her act then this constitutes blameless inadvertence. Defendants in this situation can still be found guilty. Mens rea and motive are not the same and can be shown to be different by the following example taken from Williams3 If your grandmother begs you to carry out a mercy killing and you do, some people might perceive this as an honourable motive. However, if this was premeditated and the intent was to kill her then this could be perceived as murder in the same light as someone killing a stranger for no reason. Murder is murder and the motive does not change the outcome of actions having culminated in a crime. Sentencing may be less punitive due to the motive of merciful killing but the act is nevertheless one of murder. This is often a difficult dilemma for jurors to understand – motive rather than intent.4 The mens rea may be established more readily if the person intended to do wrong but the consequences were not expected or anticipated. In the scenario where the target victim dies as a consequence of being assaulted, the culprit may have intended the assault but had not anticipated the victim’s death. This might, for example, be due to the fact that he was not privy to a medical condition weakening the victim’s sustainability against high impact knocks. The intention was not to murder but rather to mane.

Decisions made concerning factors involved in mens rea, as outlined above, can be investigated using a mock juror study paradigm. This enables researchers to consider the relationship between mens rea and evidential information. This of course involves court procedures and legal concerns and instructions given to jurors by the judge. Instructions are there for the benefit of the juror – often alerting them to the operationalisation of procedures and rules. More specifically, jurors are instructed to avoid reaching a verdict prior to hearing all of the evidence. In this way jurors can avoid an order effect where evidence presented early on in the case biases a verdict in favour of the defendant or victim.5,6 It has been found that jurors do pay heed to the nature of evidence presented and in particular evidence considered to be admissible or inadmissible in court. Kadish et al.,7 demonstrated that jurors are motivated by both procedural and legal concerns and that these concerns are incorporated in their final ratings of guilt. Furthermore, Fleming et al.,8 have found that jurors are motivated to correct their judgements of guilt or innocence as a consequence of procedural or legal infractions of due process. When, for example, evidence was obtained under violation of due process, jurors corrected for this regardless of whether the evidence was admissible or inadmissible in court.

Visher9, however, had previously reported that evidential issues in mock jury studies are considered to be part of the transcript framework where mock jurors are introduced to the criminal event and to the accused. According to Visher, the way in which the transcript content is then manipulated, measured, systematically assimilated and employed by jurors is often ignored in research. This often highlights the impact of non-evidential information such as the effects of race or attractiveness on decisions of guilt or innocence, simply because evidential information has taken a back seat. In fact, many studies suggest that jurors find it difficult to put aside their preconceptions, especially when it comes to sex crimes or mental health issues. In the case of the former, Ellison et al.,10 found that, when considering a simulated rape trial, jurors were reluctant to jettison their tendencies to reach a verdict based on ‘common sense’ and ‘personal experience’. In the case of mental health issues Taylor et al.,11 found that middle aged mock jurors have a tendency to misattribute the behaviour of defendants with Borderline Personality Disorder as being ‘bad’, ‘rude’ and ‘punishable’ rather than taking into account their mental health issues. Clearly, in both cases, evidential issues take a back seat.

Despite such issues, Visher9 did find that, when evidential issues are manipulated coherently with clarity of physical evidence, juror decisions are based on evidential information. In such cases jurors were less responsive to extra-legal defendant and victim characteristics. In support of this, Pickel12 has demonstrated the influence of motive on verdict and probability of insanity decisions. In this study motive information and crime unusualness were presented to mock jurors. The defendant was more likely to be judged ‘insane’ if the manner of the crime committed was atypical. And if the information about the prosecution motive demonstrated evidence of a ‘strong reasonable motive,’ the defendant was considered to be sane in comparison to the defendant who had a ‘crazy unreasonable motive.’ Clearly the motive is having an impact on decision making and is considered to be evidential information.

Of importance here is the work of Kaplan et al.,13 Their study demonstrated that mock jurors considered both evidential and non-evidential information when evaluating defendants. In this case, evidential information was manipulated by presenting circumstances of the crime in either a high or low incriminating manner. Non-evidential information was manipulated via positive, negative, neutral or ‘not at all’ accounts of the defendant’s personality. There was an interaction between the two types of evidence. As expected the more incriminating the evidential information then the higher the extent of guilt and sentencing responses recorded. Furthermore, personality descriptions, which should not bear any importance to a defendant’s guilt, had an additive effect. In Kaplan and Kemmerick’s study a negative personality description interacted with the strong evidential information such that a higher extent of guilt rating and a stiffer sentence were considered a ‘just desert’ response.

In addition to personality factors, how attractive (physically or socially) a defendant is perceived to be has also been shown to have an effect on sentencing in mock jury experiments.14 The findings here, however, are not straightforward. The defendant’s gender, for example, has been found to impact on mock jurors’ verdict and sentencing tariff. McCoy et al.,15 found a verdict leniency effect towards female defendants of sexual child abuse cases. Ahola et al.,16 found a sentencing leniency effect for female defendants in crimes of child abuse, theft and homicide. Male defendants not only received more convictions for murder than their female counterparts but were also judged to be less trustworthy.17 There are a number of explanations for this. Ahola et al.,16 believe that the traditional stereotype of males as being capable of violent crimes influences how the female defendant is perceived. Her criminal behaviour becomes accidental rather than intentional. Herrington et al.,18 consider males accused of a criminal act to be more guilty than their female counterparts as a consequence of their masculinity.

Abwender et al.,19 found, in cases of negligent vehicular-homicide, sentencing leniency was given to attractive female defendants in comparison with less attractive ones. This effect occurred only when the mock juror was female, unlike the opposite pattern demonstrated by male mock jurors. A similar attractive leniency bias for negligent vehicular-homicide was found by Staley20 In cases of theft from a vehicle, McAlexander21 found that unattractive offenders were more likely to be found guilty by female mock jurors. Recently, Shechory-Bitton et al.,22 revisited the effect of physical attractiveness in decisions of punishment for crimes of swindle. They found that a male victim swindled by a female is held more accountable if she is unattractive. Moreover, in this case the male victim is judged to be more accountable for what had occurred when being judged by a female mock juror. There was an inverse relationship between victim-offender blame, such that no attractiveness leniency bias occurred when the swindler was attractive.

Although the level of attractiveness of the defendant clearly has a bearing on mock jury decision making, a number of studies have shown that this can be attenuated, or even eliminated, by manipulating other factors. Martin23 examined the effects of physical attractiveness, the type of crime committed (i.e. murder, assault, maim, theft and property damage), intent (responsibility versus diminished responsibility) and victim gender on male and female mock juror punishment ratings. Punishment ratings across male and female jurors failed to differ significantly even when the variables of attractiveness, type of crime committed and intent were added to the analyses. A significant interaction was uncovered, however, when the gender of the victim was considered in relation to attractiveness and intent. Punishment ratings were higher when the victim was male. There was a significant effect of intent on victim gender, where punishment ratings were higher when the defendant was perceived as responsible in contrast to showing diminished responsibility. Attractiveness played no role in punishment decision making.

Another attenuating factor to consider is the level of justification provided by the defendant for the crime. A classic study by Izzett et al.,24 considered the influence of high or low justification for defendant behaviour with levels of high and low social attractiveness. They hypothesised that defendants with high external justification for their behaviour would be sentenced less severely than defendants with low justification. They further hypothesised that a socially attractive defendant with low external justification would be sentenced more severely than a socially unattractive defendant. Mock jurors had to rate for sentence, the defendant’s justification, and social attractiveness, how guilty they felt the defendant was and the level of defendant responsibility for perpetuating the crime. Sentences received indicated no main effect of attractiveness but did for the justification variable. In cases of high justification the defendant was treated more leniently. The attractive defendant was sentenced more severely when external justification was low but leniently when it was high. The attractiveness variable clearly had an effect on sentence ratings. Alicke25 introduced the Culpable Control Model to account for the psychological processing used when making evaluations about responsibility and blame. Hence, when determining a defendant’s guilt, people evaluate negligence and harm caused in relation to the extent of responsibility and blame.

Stereotypes and the ‘halo effect’26,27 have been examined as ways of accounting for why highly attractive people tend to be perceived in a more positive light. This even extrapolates to the domain of the criminal justice system. Downs et al.,28 found that highly attractive defendants in misdemeanour cases received less in fines than unattractive defendants. They explain this by the stereotypical perception of attractive defendants being virtuous which should be rewarded or acknowledged (or an appropriate ‘just desert’ decision;29 through lenient sentencing.28 Downs and Lyons further suggest that jurors perceive unattractive defendants as transgressors and therefore, to maintain equity through ‘just desserts’, they are given harsher sentences.28,30 Unlike the halo effect which leads jurors to apply positive characteristics to defendants which, in turn, leads to assumptions of innocence, stereotypes lead to generalised beliefs, regardless of an individual’s good or bad traits.

Past research indicates that some of the halo and stereotype effects on sentencing are influenced by the intentionality and the severity of the crime. This thus supports the interactive findings of attractiveness and justification and motives on decisions of sentence as reported in previous research.13,24,31 The influence of attractiveness might therefore depend upon the type of crime and evidential information presented. Sigall et al.,31 claimed that under these experimental conditions the attractiveness-leniency effect might cancel itself out. Lieberman32 incorporated experiential or emotional and rational processing as part of a mock juror study to establish whether an attractive-leniency effect was found under variations of information processing. His research examined whether experiential processing would produce a defendant-attractiveness/leniency effect. Before deciding the monetary damages rewarded to the plaintiff in a civil trial, mock jurors were motivated to think either experientially or rationally. They were shown a photograph of either a high or low attractive defendant. Lieberman found that the plaintiff was awarded lower damages when the defendant was attractive and the mock juror processed information whilst in the experiential mode. This attractive-leniency effect however, was lost when in the rational mode. So here is another situation where the attractive-leniency effect was degraded.

As pointed out by Visher9 when evidential information is ignored or not reliably manipulated, non-evidential factors tend to be exaggerated. Indeed Mazzella et al.,33 found from their meta-analysis of experimental research on non-evidential information presented to mock jurors, that it was advantageous for defendants to be attractive, female and of high social economic status (SES). Stewart34 and Rector et al.,35 found that defendant attractiveness correlated significantly and negatively with levels of punitiveness, thus demonstrating the attraction-leniency effect. By concentrating on the ethnicity of the defendant as non-evidential information, ForsterLee et al.,36 found that jurors were most lenient in sentencing with White defendants who murdered White victims. Female jurors were more punitive than male jurors toward the Black defendant. ForsterLee et al.,36 concluded that jurors processed evidence systematically in ‘homo-race’ trials but employed a combination of systematic and heuristic processing in cases of ‘hetero- race’ trials. Furthermore, female jurors were more likely to engage emotive responses when the victim was Black.

This research demonstrates that there might be a sex of the juror effect operating here. This is not a new idea as Bloomstein37 stated in 1968 that ‘women jurors are thought to be harder on their own sex.’ The findings in this area are, however, ambiguous. Nagel et al.,38 for example, uncovered evidence that, in general, males favour male defendants and females favour female defendants. Stephen39 also found an interaction between sex of the juror and sex of the defendant: both sexes were less likely to find the defendant of their own sex guilty – hence, supporting Nagel and Weitzman. Efran40 found that men judge facially attractive female defendants as less guilty than unattractive ones. Furthermore, attractive female defendants were subsequently sentenced to fewer years’ imprisonment. Recently, however, Bottoms et al.,41 uncovered evidence that men and women do respond differently to crimes when they involve child sex abuse. In a series of mock jury experiments Bottoms et al. found women were more empathic than men toward child victims and more opposed to adult/child sex. They were also more pro-women, and more inclined than men to believe children in general. These tendencies meant that the women in these studies were more likely than men to draw on feelings of empathy for the victim when determining guilt. In summary previous mock juror studies have uncovered mixed findings. Some studies have shown that evidential information overrides non-evidential factors such as levels of attractiveness, gender and intent. Others, however, have uncovered robust effects of these non-evidential factors. It is not surprising that in some cases mock jurors are seen to be persuaded by relevant factual information or by irrelevant extra-legal defendant factors such as attractiveness.

The current study manipulates both evidential (intent directly, motive indirectly) and non-evidential information (physical attractiveness) in an effort to establish which is the more influential for mock juror decision making. Furthermore, sex of the juror is considered as a possible interactive factor.

Participants

155 students from the University of West London took part in this study. The age ranged from 18 to 59 with the vast majority being of typical student age. There was almost equal numbers of males and females (79 and 74 respectively). The only condition was that participants had a good understanding and reading ability of English.

Design

There were three independent variables: intent, defendant attractiveness and sex of the ‘mock juror.’ Intent of the defendant as depicted in the fictitious transcript had three levels: the standard condition whereby the defendant does not admit to the act; the misleading condition whereby the defendant admits to the act of the crime but was not fully aware of the situation (therefore without intent) and the coerced or threatened condition whereby the defendant admits to the act with full awareness of intent. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions. The facial attractiveness of the defendant was manipulated: attractive and unattractive. An attractive or unattractive photo of the defendant was attached to the transcripts such that there were equal numbers of attractive to unattractive photos across levels of intention. The third variable was the ‘sex of the mock juror’, (approximately the same number of males and females took part). There were three dependent variables: extent of guilt (the level of guilt attributed to the defendant), sentence (the sentence fine attributed as most fitting for the offence) and probability of intent (the level of intent to commit the offence attributed to the defendant). All three were presented on an incremental scale as follows:

Extent of guilt: Scale ranged from 0 to 5 (no guilt through to highest guilt).

Sentence: Scale ranged from 0 to 10 (no sentence through to highest fine).

Probability of intent: Scale ranged from 0 to 10 (no intent through to highest percentage of intent).

Three versions of a fictitious transcript were presented to participants. The scenario depicts a car being stolen and taken to the garage to re-spray it a different colour. The case is considered as theft but handling of stolen goods in particular. The content of the three versions was consistent with only differences relating to intent (differing levels of intent) and consequently admittance to the act. Each transcript had a photo of the defendant attached which was deemed either attractive or unattractive. Previously a series of 13 photos of females in vignette and colour format were taken and rated by 24 independent raters for attractiveness on a scale of 1-5 where 1 was most attractive and 5 least attractive. Scores were analysed using Kendall’s Correlation of Concordance where two clear photos on opposing ends of the scale were statistically significantly different. These two photos were used in this study. Attached to each transcript was a score sheet with instructions. Each dependent variable was scored using an incremental scale.

Participants were approached at the university and asked if they would be interested in reading a transcript and answering a few questions afterwards. If they agreed then a quiet space in the university was found where they could read the transcript uninterrupted.

Ethical issues

This study was passed by the Ethics Committee of the University of West London.

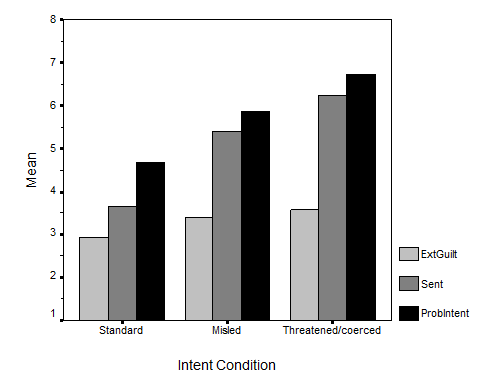

The mean ratings for extent of guilt, sentence and probability of intent across the three conditions of intent are shown in Figure 1c. There is a rise in extent of guilt, sentence and probability of intent scores with change of intent. In the standard condition, where the defendant claims to be innocent and there is no admittance of guilt or justification for the behaviour, mock jurors are more lenient in their scores for the three dependent variables. In the case of the misled and coerced/threatened conditions the extent of guilt failed to rise significantly from the standard condition or from each other (i.e. misled and coerced/threatened). Sentence and probability of intent ratings, however, increase from the misled to coerced/threatened conditions. This suggests that, in terms of extent of guilt, mock jurors perceive all three defendant cases as similar, but as the intent changes, sentence and probability of intent scores increase. In the misleading condition, the defendant argues that she did not realise what was happening, unlike the coerced/threatened condition where she claims that her criminal conduct was due to a forced situation that she felt unhappy with. It therefore makes sense that probability of intent would be perceived as most pronounced by mock jurors judging the coerced/threatened condition – as the full intent was there after all. Sentence again reflects this way of thinking and fits with the notion of a difference between intent and motive (the reason, whether conscious or unconscious for the course of action). In this case the intent is having a greater impact on mock jurors than the underlying motive for the action.

Figure 2 shows the mean ratings for extent of guilt, sentence and probability of intent across the two levels of defendant attractiveness with conditions of intent collapsed. The scores for all three dependant variables for attractive and unattractive defendants were similar. Figure 3 shows the mean ratings for extent of guilt, sentence and probability of intent across the two levels of gender of the mock juror with conditions of intent and defendant attractiveness collapsed. Male and female ratings are very similar for all three dependant variables. A Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was performed on these data. A significant difference was found across the three levels of intent for extent of guilt (F(2,135)=3.799, p<0.05), sentence (F(2,135)=7.438, p<0.001) and probability of intent (F(2,135)=4.993, p<0.01). Post hoc Scheffe test for unplanned comparisons revealed that the significant differences across the variable of intent lay between the following groups: Extent of Guilt - standard and coerced/threatened (mean diff = -.63, p<0.05); Sentence – standard and misled (mean diff =-1.74, p<0.05) and standard and coerced/threatened (mean diff =-2.59, p<0.05) and Probability of Intent standard and coerced/threatened (mean diff =-2.04, p<0.05). The direction of difference can clearly be seen in Figure 1 where the extent of guilt, sentence and probability of intent scores increase with increasing intent and justification (motive). There were no significant findings for attractiveness of the defendant for extent of guilt (F(1,135)=0.069, p>0.05), sentence (F(1,135)=0.107, p>0.05) and probability of intent (F(1,135)=0.377, p>0.05). Figure 2 clearly shows the similarity of rating across the conditions. There were no significant findings for gender of the juror for extent of guilt (F(1,135)=0.001, p>0.05), sentence (F(1,135)=0.292, p>0.05) and probability of intent (F(1,135)=0.028, p>0.05). Figure 3 clearly shows the similarity of rating across the conditions. There were no significant interactions found.

Figure 1 The mean ratings for extent of guilt, sentence and probability of intent across the three conditions of intent.

Findings are consistent with the notion that mock jurors rely on evidential information to inform their judgements of extent of guilt, sentence and probability of intent. In contrast to a number of previous studies, an attractiveness-leniency effect for the dependant variables was not found in this study. Furthermore, there is no support for the notion of there being a difference in decision making between men and women. The variable of intent appears to be the only significant evidence item influencing both male and female mock jurors alike in deciding extent of guilt, sentence and probability of intent.

The probability of intent variable is important to the appropriateness of the manipulation of intent across the three versions of the transcript (refer to Figure 1). This acts as a good indicator of variable reliability. Despite there being a significant difference for probability of intent across the three motive conditions, post hoc analysis reveals that this significant effect arises from the difference between the standard and the coerced/threatened conditions. Of relevance to our understanding of the levels of intent outlined in the transcripts and their possible impact on decision making is Section 22 of the 1968 UK Theft Act42 (given that the study was conducted in the UK). This stipulates that a person is guilty of handling stolen goods if they know or believe them to be stolen. Also if they dishonestly do one of the following: receive the goods; arrange to receive them; undertake their detention, removal, disposal or realisation by or for the benefit of another; arrange to undertake the above; assist in their detention, removal, disposal or realisation by or for the benefit of another; arrange to assist in the above.

The collection, handling and detention of a ‘stolen’ vehicle are key to understanding the manipulation of the variable of intent depicted in the court case transcript. In the standard condition the defendant denies stealing the car; in the misleading condition the defendant denies stealing the car but admits to ‘collecting’ it and taking it to the garage for body work and finally, in the coerced/threatened condition the defendant admits to stealing the car but only for the purpose of ensuring the safety of her children. The variation of intent is mainly concerned with the level of realisation of theft and handling of stolen goods. It is therefore not surprising that, across the three levels of intent, the probability of intent increases with increasing likelihood of knowing and believing the handling of the car would be theft. That is, taking it without the consent of the owner. Of interest is the fact that sentencing increased with increasing ‘justification’ of the action which could be considered as the motive element of the act. It appears that mock jurors in this study are giving the benefit of the doubt to the defendant in the standard condition. This also appears to be the case for the extent of guilt ratings. Despite a significant difference for ‘extent of guilt’ across the differing conditions of intent, post hoc analyses reveals that this difference lies with one comparison – between the standard and coerced/threatened condition. This suggests that on account of ‘extent of guilt’ the defendant in the misleading and coerced/threatened conditions is regarded as being equally culpable. It appears that no exception is made for the defendant who was misled or coerced/threatened into committing an act of theft. They are ‘tarred with the same brush’ it would seem regardless of the motive being different. In accordance with the 1968 UK Theft Act, it would appear mock jurors believe that the defendant who was ‘misled’ or ‘coerced/threatened’ had knowledge that the car might have been taken without the consent of the owner. No such assumptions can be made for the defendant who pleads not guilty in the standard condition.

Where does this leave us in terms of the mens rea of theft? There are two elements: dishonesty and intention to permanently deprive someone, which makes it a crime of specific intent. Dishonesty is up to the jury to decide. Jurors need to consider whether the defendant believes he or she has the right to deprive another person of their car on a permanent basis. Would the victim concerned have consented to the car being taken if the circumstances had been made clear? This is equivalent to the neighbour borrowing goods with permission. Is taking the car a reasonable action when the defendant acted in the belief that the true owner cannot be found? More specifically in the case of handling goods, for mens rea to stand, there has to be proof of a defendant’s knowledge or belief that the goods are stolen. This is not always easy to establish which is why a defendant’s previous involvement in theft/handling is admissible in court as evidence of mens rea. This can be as far back as the last 12 months for the involvement in theft/handling but for a conviction of theft/handling it increases to the last 5 years (again under UK law). In the transcript details there is mention of the defendant having two previous convictions for theft/handling and the modus operandi being exactly the same as the current charge. This information is available to all mock jurors participating regardless of varying conditions of intent. Clearly, mock jurors are giving the defendant who pleads not guilty the benefit of the doubt even though there is a history of convictions for theft/handling.

It is interesting that physical attractiveness appeared to have no effect on juror decisions of defendant culpability in the current study. The attractive-leniency effect, which has been well documented in previous studies, did not appear to be a factor in decision making here. As pointed out by Visher9 it might be that evidential information is the more robust factor influencing jurors’ decisions of guilt or innocence when there is a choice between evidential and non-evidential information. Jurors might be influenced more directly by non-evidential factors in the absence of or attenuated factual information pertinent to the defendant (as is the case of a defendant’s intent and evidence for this). Lieberman32 found that the attractiveness-leniency effect was degraded when mock jurors were encouraged to process information in a rational mode; that is, one reliant on cognition, logic and deduction. The opposite was true when mock jurors used an experiential mode, where they conceivably drew on emotional responses and experiences. It is possible, whilst in the experiential mode, that mock jurors utilise stereotypes to aid their decision making. This could equally be the case in studies where there is little evidential information to guide their decisions and so they might resort to person perception. That is, they may have relied on stereotypes; one stereotype being that attractive people are nice to look at and therefore they are nice! The ‘halo’ effect might also be used to aid decision making in the absence of substantial hard evidence. Visher9 suggest that the level of manipulation of evidential versus non-evidential information might be the very factor influencing whether mock jurors are persuaded by the facts or someone’s appearance. In the current study it would appear that the facts in the guise of the defendant’s intent override physical attractiveness.

The importance placed on evidential information and the consideration of the defendant’s intent applies equally to male and female mock jurors in this study. Unlike ForsterLee et al.,36 study, neither sex was encouraged to adopt an emotive or rational processing strategy. There is no reason therefore to suspect that female jurors are any less objective in analysing evidence, formulating sound hypotheses based on deduction and similar story telling than their male counterparts.43 Additionally, they should be no more persuaded to draw upon non-evidential information and entertain different person perception interpretations than their male counterparts. Hence, in our study, it would appear that there is no foundation for a difference of evidence utilisation across gender. It is entirely possible, however, that had we used a child sex abuse scenario, then we might have uncovered a gender difference in decision making. This was certainly the case in the mock jury study of Bottoms et al. (2014) where women were observed to be more empathetic than men towards the child victims. Hence, there may be some specific forms of criminal activity which lead to broadly divergent reactions across gender.

This study demonstrates that male and female mock jurors were more considerate of evidential than non-evidential information. The levels of defendant intention (considered as evidential information) influenced mock juror decisions of extent of guilt, sentencing and probability of intent. It appears that the intent, and not the justification (or motive) for the criminal behaviour, negates any attractive-leniency effect and ensures punitive treatment in terms of increased sentence. Intent initiates a ‘just deserts’ philosophy – where the behaviour should be punished accordingly. Where there was no intent (or at the very least it was not directly implicated from the defendant) benefit of the doubt was given and this is supported by lower extent of guilt, sentence and probability of intent ratings. In this case, attractiveness of the defendant appeared to be overpowered by the defendant’s mens rea.

None.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Taylor, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.