eISSN: 2575-906X

Short Communication Volume 8 Issue 1

Alumnus, Faculty of Pharmacy, Dhaka University, Bangladesh

Correspondence: Abdul Kader Mohiuddin, Alumnus, Faculty of Pharmacy, Dhaka University, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh

Received: November 27, 2025 | Published: December 17, 2025

Citation: Mohiuddin AK. Global green betrayal: excuses are plenty, forests empty, and truth overlooked. Biodiversity Int J. 2025;8(1):40-50. DOI: 10.15406/bij.2025.08.00219

Deforestation is accelerating across regions as ecosystems face mounting human pressures. Biodiversity is collapsing at unprecedented rates, with wildlife populations declining by nearly three-quarters and economic losses reaching trillions of dollars each year. Agricultural expansion, industrial extraction, climate-driven wildfires, and conflict are driving record levels of forest degradation, particularly in tropical regions where ecological resilience is already fragile. These combined pressures are pushing the planet toward a critical sustainability threshold, underscoring the urgent need for decisive global action to safeguard the world’s remaining forests before they are lost irreversibly. Yet public trust in climate governance continues to erode as global leaders host consecutive U.N. summits in major fossil-fuel-exporting and high-emission nations—including the United Arab Emirates, Azerbaijan, and Egypt—while the worldwide backlash over COP30’s Amazon tree-felling lays bare the deeper climate challenges threatening the credibility of international sustainability commitments.

Keywords: tree-cover loss, permanent land-use change, tropical deforestation, armed conflicts, biodiversity decline, agricultural expansion, climate-driven wildfires, mining-related loss, wildfires

Biodiversity loss has become one of the most urgent sustainability challenges of the twenty-first century. Although scientists estimate that Earth may host between 100 million and 1 trillion species.1 only about 2 million have been formally described, underscoring how little is understood about the biological systems upon which human well-being depends.2 The World Wide Fund for Nature’s Living Planet Report shows that nearly three-quarters of global wildlife populations have disappeared in just five decades, a level of ecological decline that now disrupts ecosystem integrity, food systems, and economic stability worldwide.3

Today, roughly five million hectares of forest are destroyed each year, with 95% of this loss occurring in tropical regions.2 Socioeconomic pressures—from population growth and rising GDP per capita to disruptive shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2008 financial crisis—continue to shape where and how quickly forests disappear. Research shows that population size, economic development, colonial history, geographic conditions, and existing forest cover all influence deforestation differently in countries with large versus limited forest resources.4 Meanwhile, industrial activities such as logging, mining, and large-scale agriculture keep pushing deeper into forest landscapes, driven by soaring global demand for beef, palm oil, timber, soy, and paper, and accelerating destruction at an unprecedented scale.

A Nature study shows that wealthy nations—including the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, China, Germany, and France—outsource their demand for commodities in ways that trigger fifteen times more biodiversity loss abroad than within their own borders. This global imbalance becomes clear when looking at consumption patterns: for example, demand in the U.S. and the U.K. alone is linked to 13% of all forest loss occurring outside their territories.5 The same pattern holds for mining. Just six countries—many of them geographically distant from the extraction sites—are responsible for over half of the world’s mining-related deforestation. One striking case is the European Union, whose imports drive 85% of its total deforestation footprint in other regions, well beyond the continent’s own borders.6

Alarmingly, Global Canopy reports that in 2024, 150 of the world’s largest financial institutions directed nearly $9 trillion into sectors directly linked to deforestation.7 Its latest review of the 500 most influential real-economy companies reveals that nine forest-risk commodities—beef, leather, soy, palm oil, timber, pulp and paper, cocoa, coffee, and rubber—collectively account for more than two-thirds of all forest loss worldwide.8 Political deadlock has further intensified the global forest crisis. For example, the EU’s Deforestation Regulation, designed to hold supply chains accountable for forest loss, has faced repeated delays since its approval in April 2023. These setbacks are driven by pushback from the U.S., major commodity-producing countries, farmer protests, the ongoing war in Ukraine, and opposition from a right-wing majority in the European Parliament.9,10

Forest decline and its multidimensional impacts on people and planet

Forests—home to more than 80 percent of the world’s threatened species—remain central to global sustainability because they support food security, economic stability, and the livelihoods of more than 1.6 billion people, including nearly 70 million Indigenous Peoples.11 Yet more than one-eighth of global greenhouse gas emissions now arises from deforestation and forest degradation, linking ecosystem collapse directly to climate instability.12

Deforestation amplifies environmental stress by increasing pollution, disrupting water and carbon cycles, and accelerating climate change. These cascading pressures trigger inflammation and oxidative stress, elevating the risk of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and other non-communicable diseases. Research in Nature indicates that deforestation-driven erosion and rising chemical pollution contaminate soil, air, and water, intensifying exposure pathways responsible for an estimated 5.5 million pollution-linked cardiovascular deaths worldwide in 2019.13 Another Nature study shows that tropical deforestation contributes to dangerous local warming, resulting in over 28,000 heat-related deaths annually and exposing hundreds of millions—particularly in Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Americas—to increasing heat stress and sharply reduced safe working hours.14

A global meta-analysis found that greater exposure to forests and green spaces is associated with lower risks of asthma, lung cancer, and COPD mortality, with protective effects influenced by age and proximity to greenery.15 Country-level analyses across 230 nations also reveal that larger forested areas are significantly linked to lower prevalence of mental health disorders.16 Table 1 reflects key health impacts linked to deforestation across different regions.

|

Study place |

Investigation details |

Deforestation-related health outcomes |

|

Indonesia |

Effect of forest loss on child health and education |

Higher malaria incidence; greater risk of academic delay17 |

|

Southeast Asia |

Link between deforestation, environmental change, and Nipah virus |

Human-driven land use (deforestation, agriculture, urbanization) promotes NiV transmission18-20 |

|

Nigeria |

Two approaches to quantify deforestation’s impact on children |

Increased risk of cough, diarrhea, and malaria via soil pH, organic carbon, and cation levels21 |

|

Peruvian Amazon |

Spatial Durbin Model analysis of deforestation and malaria |

Loss of 1,000 hectares of forest linked to 69 additional malaria cases 22 |

|

Brazil |

Spatiotemporal analysis of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) and deforestation (2001–2023) |

Deforestation significantly raises VL incidence, especially in areas of intense land-use change 23 |

|

Deforestation and COVID-19 in Indigenous populations |

Strong link between deforestation and COVID-19 spread before vaccination 24 |

|

|

The DR Congo (DRC) |

Human–animal–environment risk factors for Monkeypox (mpox) |

Forest cover changes, via deforestation or conservation, alter mpox transmission risk 25 |

|

Mexican Municipalities |

Deforestation impact on infant health |

Higher likelihood of low birth weight and low Apgar scores 26 |

Table 1 Deforestation and its health consequences: evidence from recent case studies

The World Health Organization estimates that current global deforestation trend drains roughly $10 trillion from the global economy each year, driven by mounting healthcare costs and crop losses as pollinators disappear.27 The World Bank adds an equally sobering projection: ongoing deforestation could shave $2.7 trillion off global GDP annually, with low- and lower-middle-income nations facing the steepest fallout—potentially more than a 10 percent GDP drop by 2030.28

Deforestation threatens the livelihoods, food security, and cultural identity of local and Indigenous communities by depleting clean water, fertile soil, and climate stability. While it may offer short-term profits, the long-term economic costs—from lost ecosystem services to land degradation and higher disaster risks—far outweigh any immediate gains.29 Each year, tens of thousands of animal species disappear, while human-generated mercury emissions further pollute the atmosphere. Forest loss disrupts rainfall patterns, accelerates soil erosion, and intensifies floods and droughts. Indigenous communities are displaced, livelihoods are undermined, and the risk of zoonotic disease spillover increases.30 Among rural populations, deforestation exacerbates poverty, deepens social inequalities, and weakens community resilience, highlighting the urgent need for effective conservation and community empowerment measures.31 Businesses also face supply chain disruptions, litigation risks, and reputational damage, while financial institutions contend with elevated credit, market, and liquidity risks from nature-related losses. Collectively, these impacts threaten macroeconomic stability through reduced productivity, inflationary pressures, and increased financial system vulnerability.32 Altogether, deforestation poses severe environmental, health, social, and economic risks that demand urgent action.

Historical and contemporary dynamics of human-driven deforestation

Human-driven deforestation—rooted in land clearing for crops and livestock since as early as 10,000 BC—has become one of the planet’s most enduring and damaging environmental legacies.33 Half of the world’s forests disappeared between 8,000 BCE and 1900, yet the remaining half vanished in only the last century, underscoring an escalating sustainability crisis.34 Prior to the twentieth century, temperate regions such as Europe, Russia, China, North America, and Australia absorbed most of this pressure, driven by rising demand for food, fuel, and timber.35

Between 1800 and 1914, global forest loss surged, not primarily because populations were expanding, but because Europe’s intensifying appetite for commodities and raw materials reshaped land use across continents.36 This market-driven transformation depleted ecosystems, destabilized natural capital, and forced rural communities—especially in non-Western regions—to depend on increasingly volatile global supply chains. Over the past 300 years, an astonishing 1.5 billion hectares of forest—an area roughly one and a half times the size of the United States—have been cleared, highlighting a central sustainability dilemma: economic growth has been achieved at the expense of ecological stability, long-term resilience, and the biodiversity upon which human well-being ultimately depends.34

The scale and pace of tropical forest loss underscore a critical sustainability challenge. According to data from the University of Maryland’s GLAD Lab, published on the World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Watch platform, approximately 6.7 million hectares of tropical primary forests were lost in 2024—a more than 150% increase over the past two decades, marking a twenty-year peak in forest destruction. To put this in perspective, the area lost is roughly equivalent to the size of Panama and nearly twice the size of Belgium or Taiwan, and represents almost double the forest loss recorded the previous year.37,38

Brazil bore the brunt of forest loss, shedding an area comparable in size to Belgium or the U.S. state of Massachusetts, primarily due to extensive wildfires.39 Meanwhile, Bolivia experienced a staggering 200% increase in primary forest loss, exceeding the size of Montenegro and driven largely by fire rather than the agricultural expansion that dominated previous years.40 Climate change, unsustainable land use, and unusually dry conditions linked to El Niño are fueling a self-reinforcing cycle in the Amazon, where increasing forest vulnerability amplifies both the frequency and intensity of wildfires, further weakening the ecosystem and accelerating long-term degradation.38

The DRC’s vast forests—forming part of the Congo Basin, the world’s second-largest rainforest—cover two-thirds of the country and support more than half of its largely rural population, who depend on them for food, fuel, and income, often at significant environmental cost.41 The country offers a distinct lens for understanding ecological change, as severe fragmentation from mining, rapid urban expansion, and recurring conflict creates a real-time setting to study tipping points, conflict-driven regrowth, and the ways instability reshapes landscapes.42 In 2024, the DRC’s primary forests shrank by an area roughly the size of Delaware, marking a 150% increase in loss driven by a combination of armed conflict and widespread wildfires.43

In Indonesia, deforestation intensified at lower elevations and along coastal areas between 1950 and 2017 due to the rapid expansion of plantations—except in Java and Bali, where most forest loss occurred earlier—and although protected areas slowed this trajectory, they still experienced edge-related degradation as plantations advanced.44 In 2024, Indonesia had lost forest cover comparable in size to Luxembourg or even the Greater Tokyo area, with nearly half of these losses lacking a clearly identifiable cause.45,46

Global drivers of accelerating deforestation and tree-cover loss

Biodiversity now confronts one of the most profound sustainability threats of the modern era: the rapid and relentless loss of forests. With the global population now surpassing 8 billion, pressure on the world’s forests is escalating at an unprecedented rate. Rapid urbanization and industrial expansion are driving large-scale deforestation, as expanding cities, roads, and infrastructure encroach upon previously intact forested landscapes. Research indicates that the growing demand for land and forest-derived resources intensifies both legal and illegal logging, leaving remaining forest fragments ecologically isolated, highly vulnerable, and poorly connected.47 Concurrently, industrial activities—including logging, mining, and large-scale agriculture—continue to clear vast tracts of forest, while the surging global appetite for commodities such as beef, soy, palm oil, and paper compounds this loss, accelerating ecosystem degradation worldwide.48

Permanent land-use change: a major driver of global forest loss

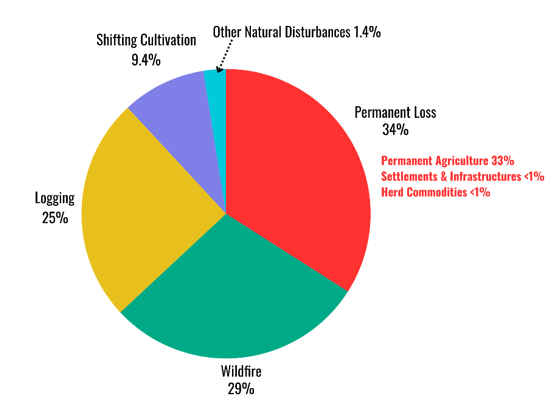

Between 2001 and 2024, over a third of global tree-cover loss—168 million hectares, an area larger than Mongolia—was likely driven by permanent land-use change, according to the World Resources Institute using Global Forest Watch data (Figure 1). The impact is even more pronounced in tropical primary rainforests, where more than 60% of forest loss—50.7 million hectares, roughly the size of Thailand—can be attributed to permanent land-use conversion.49

Figure 1 The pie chart shows an estimated 515 million hectares of global tree-cover loss between 2001 and 2024, with 34% deemed permanent. The WRI and Google DeepMind dataset, based on nearly 7,000 samples and available via Global Forest Watch, uses a neural-network model with 90.5% accuracy to identify forest-loss drivers. Regional patterns indicate that logging dominates in Europe, permanent agriculture in the tropics, and wildfires in Russia, North America, Asia, and Oceania (Figure generated by Canva Illustrator).

Methodology

This narrative review integrates leading global datasets, peer-reviewed studies, and major international reports to examine the drivers and patterns of accelerating deforestation. Where recent scholarly data are limited, verified news media reports have been incorporated to provide updated context. While the discussion of climate and socioeconomic impacts is addressed under their respective subheadings, the review primarily focuses on key drivers such as agricultural expansion, industrial extraction, human-driven wildfires, and conflict-related deforestation, with additional attention to the international political dynamics that exacerbate forest loss. The synthesis is structured to inform and support environmental scientists, ecologists, conservation practitioners, and policymakers engaged in forest governance, biodiversity conservation, and land-use planning.

Agricultural and industrial drivers of global deforestation

Over the past three decades, crop and cattle production have become dominant drivers of global deforestation, progressively reshaping landscapes across tropical and subtropical regions. Between 2000 and 2018, FAO’s global Remote Sensing Survey found that agriculture—particularly livestock grazing—accounted for nearly 88% of forest loss, a sharp escalation compared to earlier estimates.50

Palm oil cultivation, livestock grazing, and the production of beef and animal feed now account for more than 40% of global deforestation,51 with cattle pasture alone eliminating over 45 million hectares between 2001 and 2015 and soy cultivation for animal feed clearing an additional eight million hectares—together an expanse slightly larger than Spain and just under the size of Texas.52

In South America, for instance, a region producing a quarter of the world’s beef, cattle production surged 70% between 1990 and 2020, while 90 million hectares of degraded pasture continue to drive deforestation (Costa et al., 2025). Overall, agricultural expansion—including both crop and livestock production—was responsible for 80–86% of global deforestation between 2001 and 2022 and from 1990 to 2020, global forests declined by 7.1%, with agricultural expansion and population growth identified as the primary forces behind this loss.48,53,54

Accelerating forest loss driven by climate and human-caused wildfires

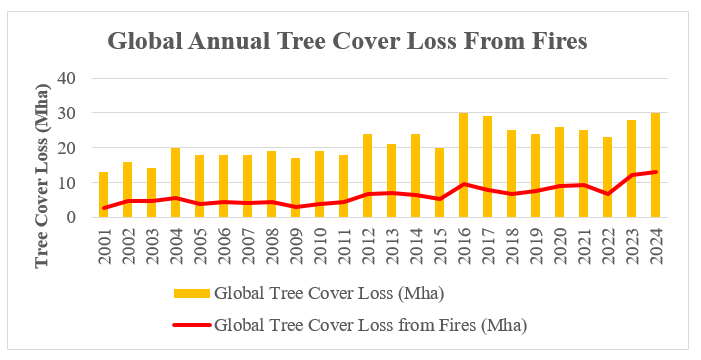

Although the role of fire in forest loss has been quantified at regional and global scales using diverse satellite sensors, these estimates remain inherently uncertain. Beyond naturally occurring wildfires, humans frequently use fire as a low-cost tool for land management and agricultural conversion, intensifying its ecological impact. Between 2001 and 2024, fires were responsible for approximately 150 million hectares of tree-cover loss—roughly the size of Mongolia or four times that of California—accounting for nearly 29% of global deforestation, with the remaining 71% driven by other human and natural factors (Global Forest Watch Live Data) (Figure 2). Alarmingly, this trend is accelerating: the annual global area of fire-induced forest disturbance in 2023–2024 was 2.2 times higher than the 2002–2022 average and three times higher within tropical regions. At the continental level, North America saw the most pronounced escalation, with fire-related forest disturbance increasing 3.7-fold over the past two decades, followed by Latin America at 3.4-fold and Africa at 2.4-fold.55

Figure 2 The annual global loss of tree cover caused by wildfires (Source: Global Forest Watch). The graph shows that, alongside rising deforestation worldwide, wildfires are becoming an increasingly significant driver of forest loss, accounting for 45% of tree-cover loss in 2024. Analysis indicates that the global area affected by fire-induced forest disturbances in 2023–2024 was 2.2 times higher than the 2002–2022 average, highlighting a sharp upward trend in wildfire-driven deforestation.

Climate change is dramatically amplifying wildfire risks, making fires 25 to 35 times more likely in some regions than they would be in a cooler world.56 According to data from the University of Maryland’s GLAD Lab, about 74.9 million hectares of forest—an area roughly the size of France, or nearly one and a half times that of Germany—were burned across 2023 and 2024.55 Kelley et al. (2025) further report that at least 3.7 million square kilometers of land, an expanse larger than India, went up in flames between March 2024 and February 2025 alone.56 Nearly half of this destruction was driven by wildfires.57

While wildfires can occur naturally in some ecosystems, in tropical forests they are predominantly human-induced, often set deliberately to clear land for agriculture and frequently spreading uncontrollably into adjacent woodlands.57 Estimates suggest that at least half of global forest loss stems from a combination of natural and human-driven fire processes, including wildfires and intentional burning associated with land grabbing, commodity-driven deforestation, and shifting cultivation.58,59 In Indonesia, for instance, approximately 60% of forests burned between 2015 and 2016 were subsequently converted into palm oil plantations, underscoring the direct link between fire use and land ownership change.60 Similarly, across parts of Africa, landowners frequently set fires on or near their properties, destroying forested areas to expand pastureland, further accelerating deforestation and landscape degradation.61

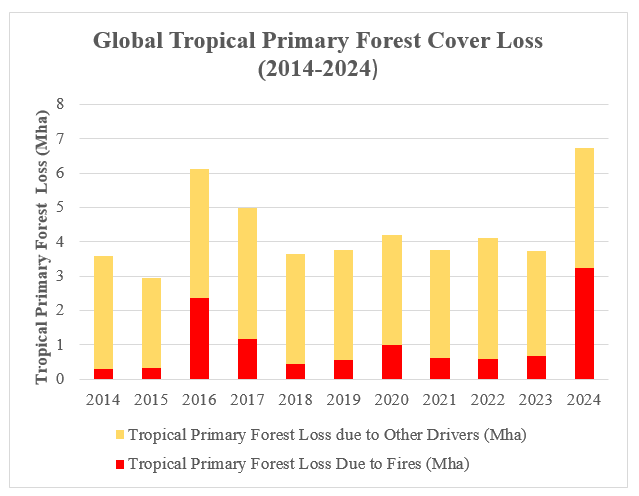

During severe fire years such as 2016 and 2024, more than a quarter of all fire-related forest loss occurred in tropical regions.55 Tropical primary forests were particularly hard hit, with fires accounting for nearly half (49.5%) of their total loss in 2024, nearly four times the 13.3% recorded in 2023,62 representing an 80% increase in loss year-over-year (Figure 3). Analyses from the University of Maryland further show that the world was losing forest cover at a rate equivalent to 11 football fields every minute in 2022, a pace that surged to 18 football fields per minute by 2024.37,63

Figure 3 The global trend in tropical primary forest cover loss over the past decade (Source: University of Maryland’s GLAD Lab). The data highlight that tropical primary forests were particularly affected in 2016 and 2024, with fire-related losses in 2024 nearly quadrupling compared to the previous year, accounting for almost half of all tropical primary forest loss worldwide.

Mining expansion and the global forest crisis

Miners worldwide are locked in a fierce race for mineral wealth, forgetting that the true treasures lie in the lush greenery of nature—nurturing biodiversity for centuries and sustaining human life itself. While global leaders proclaim their devotion to saving the planet, their actions tell another story: in the name of progress, they pursue relentless excavation, mining the world’s poorest lands as if they belong to another planet.64–69 According to authors from the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), mining—currently the fourth-largest driver of deforestation—has a far-reaching impact, affecting up to one-third of the world’s forest ecosystems when indirect effects are considered. Mining activities have accelerated alarmingly, with more than one-third of all mining-related deforestation over the past 20 years occurring in just the last five, and this upward trend is expected to continue.6 An abstract presented at the EGU General Assembly 2025 reported that 236,028 mining areas worldwide were associated with 9,765 km² of deforestation—roughly the size of Puerto Rico—between 2001 and 2023, with about half linked to undocumented mining operations.70

Since 2001, global mining activity has expanded by more than 50%, fueled by surging demand for gold, coal, lithium, cobalt, and other industrial minerals.71 This rapid growth has intensified pressure on forests in every region—from the Congo Basin to the boreal woodlands of Russia. Between 2001 and 2020 alone, mining caused the permanent loss of nearly 1.4 million hectares of tree cover, an area roughly the size of Montenegro.72 A separate global analysis found that mining activities contributed to the loss of 16,785.90 km² of forest between 2000 and 2019, exceeding the land area of Hawaii.73

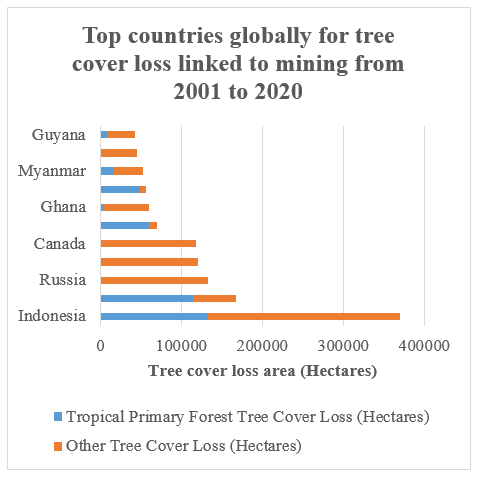

By 2022, countries such as Russia, China, Australia, the United States, and Indonesia together accounted for nearly half of global mining land use. Between 2000 and 2019, mining caused more than 9,000 km² of forest loss worldwide, including 1,374 km² in Brazil and 1,272 km² in Indonesia, placing these countries among the world’s top hotspots.74 Overall, just 11 countries—including Indonesia, Brazil, Russia, the U.S., and Canada—are responsible for more than 85% of global mining-related deforestation (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Top countries globally for tree cover loss linked to mining (Source: World Resource Institute). Between 2000 and 2019, Indonesia and Brazil together lost a combined area of forest roughly equivalent to the size of Brunei or the island of Bali, representing more than one-quarter of all mining-related forest loss worldwide.

The timeline is especially stark in the tropics. Although tropical regions host less than 30% of the world’s mining sites, they account for a disproportionate 62% of all mining-related forest loss.6,72 This imbalance is visible on the ground: open-pit gold mines in the Amazon can strip thousands of hectares of rainforest within a decade, while expanding coal operations in Indonesia routinely flatten forested mountain ranges in just a few years.

A WWF study shows that gold and coal extraction alone contributed over 71% of all mining-linked deforestation from 2001 to 2019. Indonesia stands out as the global epicenter of mining-driven forest loss. With about 370,000 hectares of tree cover cleared, mostly for coal extraction, the country accounts for more than one-fifth of all deforestation tied to mining worldwide.6 This pressure has intensified as nickel mining—essential for lithium-ion batteries—expanded more than 700% between 2000 and 2020 to meet global demand for electric vehicles.73,74

In Sub-Saharan Africa, mining activities led to forest loss around mine sites over 2000–2020 roughly equivalent to the size of Jamaica or nearly the state of Connecticut, representing a 47.5% higher loss than comparable non-mining areas. Annual deforestation rates increased 2.6-fold following the establishment of mines. Beyond direct clearing, associated infrastructure and secondary land-use changes further drive off-site forest disruption.75 Ghana’s forests shrank by 5.9% between 2018 and 2023, while illegal gold mining surged by an extraordinary 1,917.6%, with the fastest expansion occurring from 2022 to 2023, driving severe ecological decline. Mined areas showed drastic losses in plant diversity, vegetation structure, and carbon storage.76

In South America, mining has become a major driver of deforestation. In Peru, gold extraction alone has resulted in 139,169 hectares of forest loss between 1984 and mid-2025, with Madre de Dios suffering the most severe impacts, despite temporary declines following Operation Mercury in 2019, according to the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP) and its Peruvian partner, Conservación Amazónica. Mining-linked deforestation is now spreading across the country, affecting Huánuco, Pasco, Ucayali, Amazonas, Cajamarca, and Loreto, where nearly 1,000 dredges have enabled rapid forest clearing in Indigenous territories and protected areas.77 In Suriname, mining has expanded rapidly since the mid-2000s, causing 421.3 km² of forest loss between 1997 and 2019, with 85% attributed to artisanal mining and driving a fourfold increase in deforestation on Saamaka lands after the 2007 IACHR ruling.78,79 These activities have resulted in severe forest fragmentation, sharp declines in vegetation greenness, and reduced carbon-sequestration capacity across the Amazon. Spikes in gold prices—following the 2008 boom and the COVID-19 pandemic—have further accelerated deforestation and pushed mining into previously intact forest areas.78

Colonial legacies in Brazil and the DRC have shaped resource-driven economies where mining and infrastructure are major drivers of forest loss. In the DRC, Belgium’s mining regime evolved into a post-independence system dominated by foreign companies, with artisanal and industrial mining causing deforestation up to 28 times greater than the land directly cleared.80 Home to 107 million hectares of rainforest, the DRC shows a strong pattern of indirect forest loss: artisanal mining in eastern regions directly cleared only 6.6% of 924,502 hectares between 2002 and 2018, yet indirectly spurred additional deforestation via agriculture (6.8% of 752,077 hectares) and settlements (23.9% of 23,299 hectares) around mining sites.81 Mining affects forests both directly, through pits and tailings, and indirectly, via infrastructure and supply chains, driving land cover change, biodiversity loss, and water stress. In Brazil, Portugal’s colonial legacy of plantations and mineral exports laid the foundation for modern agribusiness and mining, which have cleared vast Amazonian tracts, displaced Indigenous communities, and fueled fires.80 Indirect deforestation linked to mining can be up to 40 times larger than direct loss, with Brazil ranking second globally in mining-related forest loss at roughly 170,000 hectares cleared between 2001 and 2020, largely from small-scale, informal gold mining that opens roads, pollutes rivers, and fragments remote Amazonian forests.6,74

Mining, the pursuit of natural resources, and armed conflict are intertwined challenges worldwide. In conflict-affected Myanmar, a handful of mining sites in the eastern region bordering China exported rare earths more than twice between 2021 and 2023. Since then, mining has expanded rapidly, now spanning an area roughly the size of Singapore. In Kachin State, where mining is most concentrated, approximately 32,720 hectares of subtropical and moist forests across Chipwi, Momauk, and Bhamo—regions experiencing both mining activity and clashes between the Myanmar junta and the Kachin Independence Army—were lost between 2018 and 2024.82

Armed conflicts and post-war drivers of forest loss

Armed conflicts are a major yet often overlooked driver of unsustainable forest loss, undermining ecological stability and long-term human well-being. They frequently spark sharp surges in deforestation—particularly in protected areas—through weakened environmental governance, civilian survival strategies, and prolonged military occupation.83 During the Vietnam War, millions of acres were defoliated with Agent Orange, destroying tree cover and critical food sources for local populations.84 In Gaza and the West Bank, the targeted felling of olive trees has devastated livelihoods while heightening social and political vulnerabilities.85 Syria lost roughly one-fifth of its forests during the civil war (2010–2019) due to direct impacts like fires from shelling, displaced populations relying on wood for fuel, and indirect pressures including poverty and weakened governance.86 Across Sub-Saharan Africa, protected areas such as Virunga, Gorongosa, and several reserves in Liberia have experienced partial deforestation linked to armed conflicts.87

Cross-border and internal conflicts, combined with complex tensions over land use and distribution, have driven multidimensional deforestation in India. Since 2001, the five Northeast states—Assam, Mizoram, Nagaland, Manipur, and Meghalaya—have collectively lost more than 1.44 million hectares of forest, roughly twice the size of Luxembourg, far exceeding the national average.88 Much of this loss stems from complex ethnic conflicts and border disputes: Assam-Nagaland tensions rooted in colonial-era demarcations push communities to rely on forests, while violent ethno-religious conflicts in Assam’s Bodoland forests drive rebel control, illegal logging, and displacement.89–92 In Manipur, deforestation links to land use conflicts, illegal migration from Myanmar, and poppy cultivation.93 Jhum cultivation, mining, and quarrying are key drivers of deforestation in Mizoram and Meghalaya,94,95 fueling competition over forested land among tribal groups, settlers, and commercial actors, while refugee influxes in Mizoram and Manipur further drive clearing for settlements and subsistence agriculture, albeit with limited data available.

Armed conflicts can drive deforestation both within the country and across its borders. From 1990 to 2020, Myanmar lost over 11 million hectares of forest cover in three major waves driven by conflict dynamics, post-Cold War geopolitics, and cross-border resource extraction.96,97 In Tanintharyi, military offensives, ceasefires, and Thai-backed logging and infrastructure projects fueled timber extraction and oil palm concessions; in Kayin, counterinsurgency, road building, and later ceasefire-enabled investments drove cycles of displacement and forest clearing; and in Kachin, ceasefires, shifting alliances, and China’s commercial engagement spurred logging, agribusiness, and mining.98 Armed groups and cronies exploited these territories, creating uneven deforestation patterns. Following the 2017 Rohingya refugee influx in Bangladesh, 2,300–7,000 ha of forest around Cox’s Bazar were lost, with daily tree losses equal to three football fields, further straining resources.99–102 Dependence on forests for fuelwood, low education, and insecure livelihoods reinforced a cycle where conflict and deforestation mutually intensified. In addition, from 2021 to 2024, an overwhelming 96% of Myanmar’s tree cover loss occurred within natural forests, amounting to roughly 1.2 million hectares, according to Global Forest Watch’s dynamic data.

Armed conflicts, when intertwined with illicit crop production used to fund warfare, have dramatically accelerated deforestation, yielding severe ecological and social consequences. In Myanmar’s Shan State, ongoing conflicts drove the expansion of opium poppy cultivation, making the country the world’s largest opium producer at 1,080 metric tons in 2023, while simultaneously triggering widespread deforestation, water scarcity, soil erosion, and heightened landslide risks.103 In Lao PDR, nearly 44% of poppy plots were located within 10 km of protected areas, including 11% inside official reserves, and roughly half of recently deforested lands had been cleared within three years to make way for opium cultivation.104

Between 2000 and 2015 in Colombia, deforestation closely mirrored conflict intensity and proximity to illegal coca plantations, particularly in ecologically rich regions such as Tumaco, Catatumbo, San Lucas, La Macarena, and the Sierra Nevada. While armed conflict and coca cultivation each exerted independent pressures on forests, their combined impact was smaller than other drivers. Following the peace accord, areas with weak governance saw renewed forest loss tied to localized conflicts.105 Across Central America, narcotics-driven deforestation—commonly termed “narco-deforestation”—transformed millions of acres of tropical forest into agricultural land for money laundering, accounting for up to 30% of annual forest loss in Nicaragua, Honduras, and Guatemala. Alarmingly, 30–60% of this deforestation occurred within protected, biodiversity-rich areas, highlighting the acute environmental threat posed by conflict-linked illicit agriculture.106

While some armed conflicts can temporarily shield ecosystems by limiting human activity, these benefits are usually short-lived and often offset by deforestation and land-use changes elsewhere, as seen in Ukraine’s disrupted agriculture.83 In just two years of war with Russia, Ukraine lost nearly 600 square miles of forest—roughly twice the size of New York City—demonstrating how rapidly conflict can accelerate ecosystem loss.107 As natural gas supplies tightened and prices surged, households and industries across Europe increasingly turned to fuelwood and biomass for energy.108–112 Simultaneously, some governments loosened logging restrictions or fast-tracked timber auctions to stabilize energy markets, adding further pressure on already stressed forests. Rising energy costs, combined with EU bioenergy subsidies, have driven households to burn wood even in protected areas.113 At the same time, the conflict has spurred a surge in global food prices, prompting cropland expansion—including in Europe’s fallow lands and in countries such as the United States, Brazil, China, and India—threatening biodiversity worldwide, especially in tropical regions.114

Critically, deforestation often accelerates after conflicts due to reconstruction efforts, weak governance, and renewed commercial logging. For example, annual forest loss in Nepal, Sri Lanka, Ivory Coast, and Peru rose by 68% in the five years following conflicts—far surpassing the global average of 7.2%—primarily driven by illegal logging and agricultural expansion.115 Yet, incorporating local communities’ perceptions into peacebuilding initiatives can play a crucial role in guiding forest conservation amid post-conflict land-use changes. In Colombia’s post-conflict Antioquia region, for instance, community views on peacebuilding and reconciliation significantly shaped deforestation patterns, with areas holding pessimistic perceptions experiencing a 22.09% lower annual deforestation rate compared to neutral areas.116

In Colombia however, armed conflict, stalled peacebuilding, and deforestation are deeply intertwined. Municipalities most affected by violence have experienced the highest forest loss, with coca-growing areas facing up to triple the deforestation rates of non-priority zones during 2016–2019.117 Weak state presence and delayed implementation of the 2016 Peace Agreement have allowed armed groups and illicit economies to expand, perpetuating both violence and forest destruction rather than delivering anticipated stability. National deforestation surged 35% in 2024, rising from 793 km²—a 23-year low—to 1,070 km², with conflict-affected Amazonian regions accounting for nearly 60% of losses.118 Governance erosion in hotspots such as Tinigua and Sierra de la Macarena enabled large-scale clearing, land grabbing, and illegal operations, contributing one-quarter of the country’s 2024 deforestation. Post-accord power vacuums continue to shape forest dynamics, from the 2017 surge after the FARC peace deal to medium-scale clearing of 2,700 hectares in Chiribiquete National Park and Yarí–Yaguará II Reserve in 2024–25.119

A climate summit and the amazon: exposing the gap between climate rhetoric and environmental reality

The COP30 conference underscored a profound sustainability crisis, triggering global backlash for delivering little more than symbolic progress. While wealthy nations pledged to triple adaptation finance by 2035, they simultaneously obstructed essential measures to phase out fossil fuels, curb deforestation, and regulate critical minerals—decisions that directly undermine long-term environmental and social sustainability.120 Belém, a region in Pará already burdened by chronic deforestation, illegal gold mining, threatened Indigenous territories, and mercury-polluted waterways, became an emblem of this contradiction.121–125 The conference’s operations in Belém—marked by excessive spending, exclusionary planning, and large-scale infrastructure demands, including the felling of 100,000 Amazon trees to accommodate delegates—exposed a stark misalignment between stated sustainability goals and actual practices, further eroding trust in global climate governance.126,127

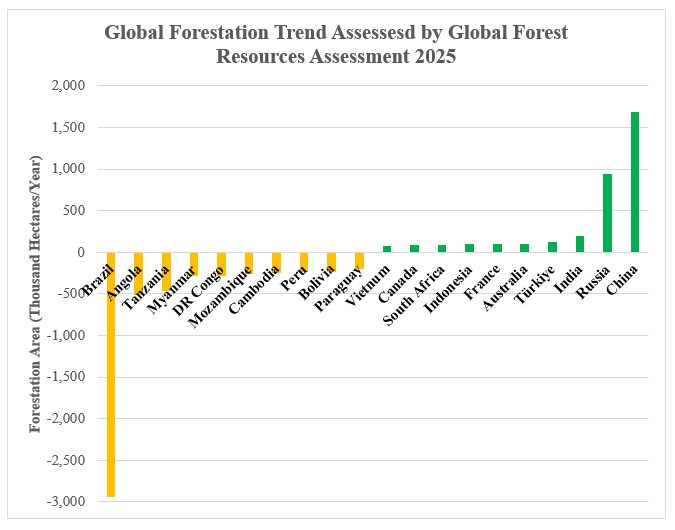

Yet this is no isolated incident. Tree felling has become a global scourge, ravaging livelihoods, development projects, and even war-torn lands. While nature nourishes the Amazon with Sulphur-rich dust carried more than 6,000 kilometers from the distant Sahara, humanity continues to strip it of life. Between 2000 and 2018, the rainforest lost an area larger than Spain, and over the past four decades’ deforestation has consumed land equal to the combined size of Germany and France—driven by cattle ranching, soy cultivation, logging, mining, and unchecked expansion, leaving its biodiversity increasingly fragile. Further, UN FAO report indicate that Brazil lost an average of 2.9 million hectares of forest annually from 2015–2025 (Figure 5).128–131

Figure 5 Top 10 Countries Gaining and Losing Forest Area (Source: Global Forest Resources Assessment 2025). The figure highlights a sharp contrast in global forest trends: countries such as China and Russia show significant net gains through large-scale afforestation, while others—especially Brazil—continue to experience steep losses.

There are numerous consequences to this level of environmental disruption. For instance, the World Bank warns that continued Amazon deforestation—including the clearing of transition zones such as the Cerrado savanna and the Pantanal wetlands—could saddle Brazil with $317 billion in annual economic losses, a figure that is seven times greater than the combined profits from agriculture, logging, and mining.132 A study published in Nature further found that in the Brazilian Amazon, the destruction of just one square kilometer of forest resulted in an additional 27 malaria cases.133 Moreover, beyond the obvious indirect health benefits of preserving the forest, another Nature study reported that reduced hospitalization costs for local Brazilians could amount to nearly $6 million in annual savings.134

Global Green Betrayal and ecological imperialism provide a sharp analytical lens on how wealthy nations’ resource footprints reflect persistent global land-use asymmetries. Prior to the twentieth century, temperate regions—from Europe and Russia to China, North America, and Australia—absorbed most land-use pressure driven by rising demand for food, fuel, and timber.35 Recent evidence shows this burden has shifted to the tropics, with high-income countries outsourcing biodiversity loss at rates roughly fifteen times greater abroad, while six distant economies account for more than half of mining-linked deforestation.5,6

Although not solely the outcome of intentional exploitation, these patterns reflect structural continuities with historical extraction systems. Market incentives and regulatory delays concentrate investment in forest-risk sectors, leaving vulnerable communities to absorb disproportionate climate and biodiversity impacts.7,8

Agricultural expansion—largely driven by livestock grazing to feed a growing global population of 8 billion—accounts for nearly 90% of global forest loss, far surpassing earlier estimates.50 Between 2001 and 2024, one-third of global tree-cover loss resulted from agriculture-related permanent land-use change, highlighting how food-system growth drives irreversible forest conversion and intensifies structural pressures on tropical commodity-producing regions.49 Addressing these challenges requires the urgent global adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices that balance high crop yields with biodiversity-friendly methods, safeguarding food security while preserving forest ecosystems.

Since 2001, fires have driven nearly one-third of global tree-cover loss, with burned areas in 2023–2024 more than double the 2002–2022 average, and by 2024, fires accounted for nearly half of the total loss—nearly quadruple 2023—highlighting accelerating climate-driven forest instability and mounting risks to global health and wellbeing.55,62 Immediate global climate finance and action are imperative, leaving behind excuses while rapidly adopting newer inventions to prevent wildfires. Financing must be mandated from profit-making global giants and countries most responsible for deforestation and the climate crisis, ensuring accountability and accelerated implementation.

Mining, currently the fourth-largest driver of deforestation, has caused cumulative losses since 2001 roughly equivalent to the size of Puerto Rico and is estimated to impact up to one-third of the world’s forest ecosystems when indirect effects are considered.6,70 Most mining operations are small-scale, located in remote areas, and rely on manual labor, making monitoring and control extremely difficult while often prioritizing poverty-driven work over ethical or environmental standards. Illegal mining, largely dominated by major business actors who bribe authorities and finance militants or terrorists, further complicates governance, suggesting that stronger international oversight and targeted anti-terrorism measures may be more effective than local enforcement alone.

Conflicts are both inherent and inevitable in human history, persisting across past, present, and future contexts. Large-scale armed conflicts—whether internal or cross-border—consistently generate two outcomes: weakened governance and population displacement, often accompanied by natural resource depletion and accelerated deforestation. Contemporary and recent crises, including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine since 2022, U.S.–China trade tensions since 2018, the Red Sea Crisis since 2023, as well as post–Cold War instability, the 2008 Global Great Recession, and the systemic shocks of COVID-19, have all disrupted global power balances and created sustained pressures on forested landscapes, yet their role as drivers of unsustainable forest loss remains largely overlooked. Imperialism, by its nature, perpetuates and often finances violent conflicts, typically to the detriment of the broader population. Collectively, these dynamics reveal a persistent intersection of geopolitical tensions, environmental degradation, and social inequities that shape global sustainability challenges.

Public trust in climate governance continues to decline as global leaders hold successive U.N. summits in major fossil-fuel-exporting and high-emission nations, including the United Arab Emirates, Azerbaijan, and Egypt.135,136 COP27 in Egypt saw critical climate goals, such as the "loss and damage" fund, overshadowed by the host nation’s political and environmental controversies.137,138 The appointment of Sultan Al-Jaber, CEO of the UAE’s state oil company ADNOC, as COP28 president-designate sparked strong opposition from climate activists and civil society.139 COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, faced sharp criticism for its human rights record, allegations of ethnic cleansing, and heavy reliance on fossil fuels, with numerous critics imprisoned in recent months.140 The COP30 controversy in Belém, Brazil—where an eight-mile stretch of Amazon rainforest was reportedly cleared to build a four-lane highway for summit infrastructure—has reinforced global perceptions of a “green betrayal.” Against a backdrop of chronic deforestation, illegal gold mining, endangered Indigenous territories, and mercury-polluted waterways, these actions expose a troubling hypocrisy. They reveal a sharp disconnect between the summit’s supposedly ambitious climate agenda and the environmentally destructive practices carried out in its name.

Our forests, the silent custodians of life, are disappearing at an unprecedented pace, driven by global warming, human greed, and relentless land-use change, as if the Earth itself mourns its own destruction. Humanity drifts helplessly in a tragic cycle of deforestation, blind to the irreplaceable gifts forests have nurtured for millennia, while evidence reveals a sorrowful tale of global green betrayal, where lofty promises of sustainability crumble under relentless tree loss. Deforestation—propelled by agriculture, industry, mining, and conflict—ravages biodiversity and dismantles the fragile systems that sustain life, with climate-fueled wildfires and permanent land-use changes pushing forests beyond recovery. Symbolic gestures at climate summits starkly expose the emptiness of global commitments, even as industrial and extractive expansion rages unchecked and post-conflict devastation deepens wounds on ecosystems and vulnerable communities. Urgent global climate action must address these intertwined crises of deforestation, biodiversity loss, and ecological inequities, holding the most responsible nations and actors accountable. Protecting forests through sustainable land use, climate-smart agriculture, and equitable governance is critical not only for the planet’s survival but also for the health, security, and well-being of current and future generations.

None.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2025 Mohiuddin. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.