eISSN: 2575-906X

Research Article Volume 2 Issue 1

Prince Saud Al Faisal Wildlife Research Center, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: M Zafar-ul Islam, Prince Saud Al Faisal Wildlife Research Center, PO Box 1086, Taif, Saudi Arabia, Tel 0096612748 1298

Received: December 09, 2017 | Published: February 15, 2018

Citation: Boug A, Islam MZ. Dating Saudi Arabian desert surface assemblages with Arabian ostrich Struthio Camelus Syriacus eggshell by c14: propositions for palaeoecology and extinction. Biodiversity Int J. 2018;2(1):83-89. DOI: 10.15406/bij.2018.02.00048

The Arabian Ostrich Struthio camelus syriacus was thought to have become extinct sometime in the late 1960s. Here we review radiometric dates for ostrich eggshell, and present 14 new calibrated accelerator mass spectrometry or C14 data, indicating that the ostrich survived in the north of Saudi Arabia until at least in the1960s. Their C14 age, derived from 14 samples, date from 384±22 to 50100±800 years from present. This study provides data of the distribution of the Arabian Ostrich through C14, and how humans extirpated the Arabian ostrich. It also assesses possible corridors for the northern and southern populations in Saudi Arabia. Genetically closely related to Arabian Ostrich is the Red-necked Ostrich (Struthio camelus camelus), which has been re-introduced in two reserves, one in Mahazat as-Sayd Protected Area in late 1990s in central Saudi Arabia; and in April 2017 a group of 10 S.c. camelus were released in ‘Uruq Bani Ma’arid Protected Area in the Empty Quarter in the southern part of the country, while it is planned to be re-introduced in al Khunfa, Harrat al Harrah reserves in the north, and As Shaiba (biodiversity area) in southeast, where the Arabian Ostrich was recorded historically.

Keywords: Carbon14 dating, arabian ostrich, struthio camelus syriacus, reintroduction, red-necked ostrich, s.c. camelus, empty quarter, saudi arabia

The Arabian Ostrich Struthio camelus syriacus1 was very similar to the Red-necked Ostrich Struthio camelus camelus as documented, but it was distinguished by its comparatively small size.2,3 Possibly, the Arabian Ostrich females were of a slightly lighter colouration.3 Within two decades of it being named, the Arabian Ostrich had become extremely rare and perhaps extinct, without any study of it being made in the wild.4

This sub-species of Ostrich, the Arabian Ostrich, was smaller than the Red-necked Ostrich, which had an excellent feathering that attracted the wealthy and noble in Arabian and European countries. Due to that, ostrich hunting became a popular pursuit. Besides selling ostrich feathers, eggs and leather were extensively used in handicraft; and sometimes the Arabian ostrich products, as well as live birds, were exported as far as China, where they call it camel bird. The introduction of firearms and motor vehicles led to significant poaching, which led to extinction of this subspecies. Once, hunting of the birds was done with bow, arrows and dogs; which allowed these flightless birds to escape, but long-range guns enabled poaching and excessive hunting, which reduced the Arabian Ostrich to extinction.

IUCN category: The Middle Eastern Ostrich or Arabian Ostrich was thought to be extinct in 1966. It is a subspecies of the most which once lived on the Arabian Peninsula and in the Near East,2,4 while Red-necked Ostrich has declined to the point where it now is included on CITES Appendix I and some treat it as Critically Endangered.5−8 The Arabian Ostrich formerly occurred in inhabited open semi-desert and desert plains of the Middle East. It is documented that in ancient times it was found north to about 33°N, and east to Kuwait, including Jordan, Syrian Desert, south into the Arabian Peninsula and apparently southern Palestine and the Sinai.9 Woodrow & Clements10 and Potts11 mentioned that Struthionids were indigenous to the Arabian Peninsula rather than immigrants from North Africa, as anticipated by Finet12 and Camps-Fabrer.13 As mentioned by Potts,11 ornithologists have suggested that the range of S. c. syriacus was between c. 34" and 22"N, or roughly from the Damascus-Baghdad line to south of Riyadh, and from Sinai in the west to the Euphrates and Gulf region in the east,14,15 while Serjeant16 suggests that the southern range of the ostrich should be extended to at least 14"N.11 The range of the Arabian Ostrich was throughout the Arabian Peninsula with the main concentration in the Rub-Al Khali and Nafud desert in the north, while there are some records from north-eastern and central parts as well.9,17 Historically, the bird seems to have occurred in two discrete relict populations: a smaller one in the southeast of the Arabian Peninsula and a larger one in the area where today the borders of Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Iraq and Syria meet.2,4

An important question has been raised that not a single S. c. syriacus bone has ever been recorded in an archaeological excavation anywhere in the Arabian Peninsula,11 which suggests that they were not hunted for meat; while recent interviews we conducted in Al Qasim suggest that ostriches were hunted for meat as well and skin and feathers were sold in local markets. As reported by Jennings4 and Fuller3 some of the last sightings of the Arabian Ostrich include an individual east of the Tall al-Rasatin at the Jordanian-Iraqi border in 1928, a bird shot and eaten by pipeline workers in the area of Jubail in the early 1940s (some sources specifically state 1941), two apocryphal records of birds suffering the same fate in 1948, and a dying individual found in February 1966 in the upper Wadi el-Hasa near Safi in Southern Dead Sea Depression in north of Petra, Jordan. This female apparently was brought to the Jordan River by floodwaters. This record is based on second-hand information but accepted with doubts (Shirihai 1996).3,14,18

The Red-necked Ostrich S. c. camelus which occurs in northeastern Africa and is considered the most closely related subspecies to the extinct Arabian form, confirmed by analyses of mt DNA control region haplotypes.19 Has been chosen for the reintroduction in 1988-89, by obtaining Red-necked Ostrich from local animal collections of Sudan origin from a private collection.20 In 1988-89, a total of 96birds were re-introduced in Mahazat as-Sayd PA in central Saudi Arabia where the present population is around 300. A group of 25 Red-necked Ostrich were re-introduced in Uruq Bani Ma’arid Protected Area in the Rub-al Khali in the south of Saudi Arabia in April-May 2017 while it is planned to re-introduced in al Khunfa, Harrat al Harrah reserves, and As Shaiba (biodiversity area), where the Arabian Ostrich was recorded historically. The objective of this paper is to establish the age of Arabian ostrich eggshells; to investigate if there is a possible corridor of northern and southern populations of the Arabian ostrich, and to propose sites for reintroduction of the genetically closely related Red-necked Ostrich in certain reserves (Figure 1).

A total of 38 eggshells were collected from the Rub al Khali or Empty Quarter mainly between Wadi ad Dawasair and Najran in southern Saudi Arabia, in Al Qasim north of Riyadh in central part and near Tabarjalin the northwest. From the literature review, certain specific sites were identified for collection of eggshells; and a few Wildlife Rangers and hunters from those areas were consulted; these reported personally to the authors about the eggshells in certain locations. Eggshells were searched and collected; some were at surface while some eggshells were buried under the sand. A few conical stones were collected near these locations of possible nests of the Arabian Ostrich, which might have been used by breeding females.

Out of 38 samples, 14 were sent to Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit of Oxford University for C14 analyses to establish the age of the eggshells; the analysis for the remaining eggshells will be carried out when funding is available. The C14 dating method was first developed in the 1940’s, by Willard Libby. He published the first set of Radiocarbon dates in 1952, and in 1960 he won the Nobel Prize. The first method for used for Radiocarbon dating involved using a Geiger counter to measure the radiation of the carbon ions. This process proved to be almost wholly ineffective because it required a very large amount of C14; 1 whole gram. C14 occurs in only trace amounts in Parts per million (PPMs). The process required monitoring the decay for a one-year period. The Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) is a technique for measuring long-lived radionuclide’s that occur naturally in our environment that made it much more practical to determining C14 levels.21,22 It involves the use of charged plates to deflect the trajectories of smaller particles while they are accelerated between these plates. Basically, the heavier C14 ions will travel in a straight path and can be collected and measured. The lighter particles will be deflected away by the magnetic field. This allows for very small sample sizes and much faster turnaround in C14 dates.

With the invention of Radiocarbon dating, it allowed scientists to obtain more exact dates than the relative dates that were available previously. The process is not 100% accurate though; there is a margin of error with each date, which can sometimes be quite large (Table 1). However, there is ongoing research into new methods and sampling techniques in order to try to reduce the margin of error, and give more exact dates.21,23 This technology is one of the ways that help us to better understand the processes that shape the world around us. Carbon 14 is produced in the upper atmosphere when cosmic radiation interacts with nitrogen gas, converting nitrogen 14 to carbon 14. These carbon 14 atoms combine with oxygen to form carbon dioxide gas, which is absorbed by plants. The plants use the carbon in the carbon dioxide to make sugar and other edible stuff. Animals eat the plants, ingesting the carbon 14. As long as the plant or animal is alive, it keeps ingesting carbon, which is a mixture of stable carbon 12 and radioactive carbon 14. When the plant or animal dies, it stops eating carbon-containing food, so its earthly remains no longer absorb carbon 14. The carbon 14 that it had when it died, however, slowly decays into nitrogen gas. So, by measuring the amount of carbon 14 left in the specimen, one can tell how long it has been since it died (http://www.scienceagainstevolution.org/v10i10f.htm, http://www.c14dating.com/int.html).

Sample # |

Site Name |

δ13C |

Year of Sample Collection & C14 |

State |

Latitude |

Longitude |

OxA-25990 |

Shuqqat Umm as Sudood in UBM |

384 ± 22 |

2010 & 2013 |

Najran |

19.39 |

45.4382 |

OxA-25981 |

Shuqqat al Khushbi |

503 ± 22 |

2010 & 2013 |

Najran |

19.24 |

45.68 |

OxA-25985 |

Shuqqat al Qarnain in UBM |

647 ± 23 |

2010 & 2013 |

Najran |

19.22 |

45.34 |

OxA-25987 |

Shuqqat Umar Jaid |

800 ± 22 |

2010 & 2013 |

Najran |

19.14 |

45.4 |

OxA-25980 |

Hamra Nathil |

838 ± 23 |

2010 & 2013 |

Najran |

18.26 |

46.39 |

OxA-23692 |

Al Wahad Sand dune |

1087 ± 25 |

2010 & 2013 |

Najran |

18.25 |

45.49 |

OxA-25988 |

Mahayyar Sudder |

1127 ± 24 |

2010 & 2013 |

Najran |

19.19 |

45.18 |

OxA-25989 |

Manadi Area |

1436 ± 24 |

2010 & 2013 |

Najran |

18.92 |

46.3 |

OxA-25986 |

Shuqqat Uma rJaid |

1482 ± 23 |

2010 & 2013 |

Najran |

19.16 |

45.29 |

OxA-23691 |

Umm ul Wahad (South of Hirjah) |

1534 ± 26 |

2010 & 2013 |

Najran |

18.22 |

45.64 |

OxA-25982 |

Al Maqta, Al Aarid, Al Khatma |

1887 ± 25 |

2010 & 2013 |

Najran |

18.4 |

45.46 |

OxA-23690 |

Shuqqat al Qarnain in UBM |

5446 ± 33 |

2010 & 2013 |

Najran |

19.16 |

45.19 |

OxA-25983 |

Shuqqat al Khushbi |

47550 ± 600 |

2010 & 2013 |

Najran |

19.13 |

45.35 |

OxA-25984 |

Shuqqat al Khushbi |

50100 ± 800 |

2010 & 2013 |

Najran |

19.13 |

45.35 |

Eggshells |

Nufud al Thwerat nearby site |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2007 |

Al Qasim |

26.55 |

44.58 |

Eggshells |

Al Wahad Sand dune |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2010 |

Najran |

18.31 |

45.55 |

Eggshells |

Al Wahad Sand dune |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2010 |

Najran |

18.31 |

45.55 |

Eggshells |

Al Wahad Sand dune (UBM) |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2010 |

Najran |

18.25 |

45.5 |

Eggshells |

Road Sharura |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2010 |

Najran |

18.29 |

45.52 |

Eggshells |

Al Wahad Sand dune |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2010 |

Najran |

18.25 |

45.48 |

Eggshells |

Shuqqat al Qarnain in UBM |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2010 |

Najran |

19.32 |

45.63 |

Eggshells |

Arg Umm ul Wahad |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2010 |

Najran |

18.22 |

45.53 |

Eggshells |

Arg al Dahboob (south of Umm al Wahad) |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2010 |

Najran |

18.17 |

45.6 |

Eggshells |

Arg al Dahboob (south of Umm al Wahad) |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2010 |

Najran |

18.17 |

45.58 |

Eggshells |

Al Mindifuin (40km of UBM) kept in Najran Museum |

Measurement |

2010 |

Najran |

18.97 |

45.96 |

Eggshells |

Al Mindifuin (40km of UBM) kept in Najran Museum |

Measurement |

2010 |

Najran |

18.97 |

45.96 |

Eggshells |

Al Mindifuin (40km of UBM) kept in Najran Museum |

Measurement |

2010 |

Najran |

18.97 |

45.96 |

Eggshells |

Shuqqat al Qarnain in UBM |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2010 |

Najran |

19.19 |

45.21 |

Eggshells |

Suqqat Um arJaid |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2010 |

Najran |

19.16 |

45.29 |

Eggshells |

Shuqqat al Khushbi |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2010 |

Najran |

19.13 |

45.35 |

Eggshells |

Shuqqat al Khushbi |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2010 |

Najran |

19.13 |

45.35 |

Eggshells |

Empty Quarter (unknown place) |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2011 |

Najran |

19.22 |

45.17 |

Eggshells |

Al Hasana in Al Qasim |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2011 |

Al Qasim |

26.56 |

44.31 |

Eggshells |

Qasimat al Waet in Tabarjal |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2012 |

Al Jawf |

30.27 |

38.36 |

Eggshells |

Nadfi in Al Hamad NE Harrat al Harrah |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2013 |

Al Jawf |

31.29 |

39.84 |

Eggshells |

Nufud al Thwerat |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2016 |

Al Qasim |

26.45 |

44.48 |

Eggshells |

Uruq al Thweret in Al Qasim |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

Record |

Al Qasim |

26.9 |

44.51 |

Eggshells |

Harrat al-Harrah |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

Record |

Al Jawf |

31.26 |

37.74 |

Eggshells |

Nafud al Urayq |

Analysis will be done when funding available |

2017 |

Al Qasim |

25.25 |

45.5 |

Table 1 Dating of Eggshells of Arabian Ostrich at Oxford University- Radiocarbon unit & other records.

Prior to the routine carbonate preparation, a series of solvent washes was applied to the eggshells, to prevent conservation contamination on the surface. The Oxford University lab, where C14 analysis was carried out made it clear that there is a 58.3% probability that it calibrates to a date of 596 cal AD but also a 37.1% probability that it calibrates to a date of 496 cal AD. Carbon 14 dating can be calibrated, and it has been discovered that certain corrections have to be made to “radiocarbon years” to convert them to “calendar years.” Knowing these correction factors allows carbon 14 measurements to yield very accurate ages, back to 4 or 5 thousand years. But beyond 5,000 years, we have to guess what the correction factors are, so the ages are only as good as our guesse (http://www.scienceagainstevolution.org/v10i10f.htm, http://www.c14dating.com/int.html)

Three complete eggshells were provided by the Najran Museum; measurements and pictures were taken in 2011 (MZ Islam in litt. 2012), while four complete eggshells were provided by the authors. One of these eggshells contains a dried dead embryo. Measurements were taken and compared with data from the Red-necked Ostrich which is considered as genetically closely related, and are captive bred at the Prince Saud al Faisal Wildlife Research Center (NWRC.GOV.SA) and re-introduced in Mahazat as-Sayd Protected Area (22.21 north & 41.79 east) central Saudi Arabia.20

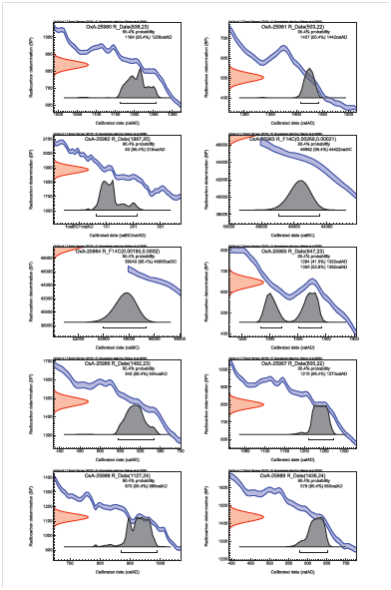

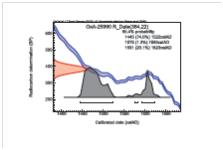

In Figure 2, the dates are uncalibrated in radiocarbon years BP (Before Present - AD 1950) using the half-life of5568 years. Isotopic fractionation has been corrected for using δ13C values measured on the AMS.24 The quoted δ13C values are measured independently on a stable isotope mass spectrometer (to 0:3 per ml relative to VPDB): Carbon stable isotope ratios are reported relative to the PDB (for Pee Dee Belemnite) or the equivalent VPDB (Vienna PDB) standard, and the chemical pretreatment, target preparation and AMS measurement.23−25 The calibration plots (Figure 2) showing the calendar age ranges, have been generated using the Oxcal computer program (v4.1) of C. Bronk Ramsey, using the `INTCAL09' dataset.26

Figure 2 Carbon dating of 14 eggshells of ostrich from Empty Quarter (courtesy: Oxford University).

Notes on reading the graphs: This plot shows how the radiocarbon measurement in BP would be calibrated. The left-hand axis shows radiocarbon concentration expressed in years `before present' and the bottom axis shows calendar years (derived from the eggshells data). The pair of blue curves shows the radiocarbon measurements on the eggshell (plus and minus one standard deviation) and the red curve on the left indicates the radiocarbon concentration in the sample. The grey histogram shows possible ages for the sample (the higher the histogram the more likely that age is).

However, as there are changes in the rate of C14 production in the atmosphere through time, it is necessary to calibrate these raw dates in order to obtain calendrical dates, and these calibrations are shown in Figure 2. These calibrated dates come with a probability term that partly derives from the measurement error, and partly from variation in the apparent rate of 14C production in the atmosphere. The C14 calibrated dates for the eggshell samples are shown in the Table 1. One of the oldest aged eggshells is of 50100±800 of present time from Shuqqat al Khushbi in the Empty Quarter; and the youngest analyzed age was of 384±22 of present time from Shuqqa Umm as Sudood in ‘Uruq Bani Ma’arid Protected Area.

Remains of old eggshells are still found in the former range of the southern subpopulation of the Arabian Ostrich, which disappeared between the 1900s and the 1920s, probably mainly because of increasing aridity wind make the eggshells appear. From the interviews in Al Qasim in central Saudi Arabia, a 94year old person mentioned that his father shot an adult Arabian Ostrich in the Al Shamasiya area (25.27north & 45.34east), when he was just a few years old. He saw a group of ostriches passing through his farm in Al Qasim. Al Qasim was considered corridor for north and south population movements. Another important record was provided by Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdullah bin Bilahid (1892-1957) in his book ‘What is close to here and far to find’ published in Arabic in 1903,27 in which he mentioned that he and his friend saw five Arabian ostriches in Faidhat Masma (26.31 north & 44.25 east) near Shaqra in Al Qasim,. He was able to kill one adult male, and sold the skin of the ostrich for 50 French Riyal, as recorded by Dr. Mohammed bin Saad bin Hussain (who reviewed Bilahid’s book and provided details to the authorsin July 2016). During the interview, another old person informed that 60 years before, one Arabian Ostrich was shot by Gretan Al Nahaetan al Sharari some 20 km NW of the Head Ranger’s Camp of Harrat al Harrah Protected Area (31.02 North & 37.93 East). In 2017, many eggshells were discovered at Nafud al Uraiq Protected Area in central Saudi Arabia.28 Also, an adult with 11 offspring is presented on the famous prehistoric Graffiti Rock near Riyadh (capital of Saudi Arabia).

During the field surveys in Empty Quarter, we often found eggshells in and around the Uruq Bani Ma’arid Protected Area. Some were considered nesting sites as complete eggs were found, with dead embryos. Key sites where samples were collected, are Shuqqa Umm al Khushbi, where C14 dating shows >5000 age. Other sites include Shuqqat Qarnain within the Reserve, Manadi Area etc as given in Table 1.

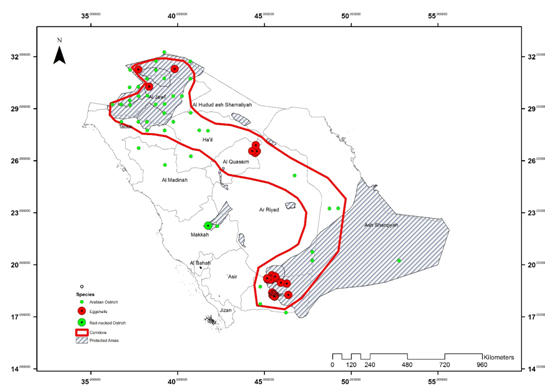

Possible corridor: There were two disjunct populations of the Arabian Ostrich in Saudi Arabia: one in the south and the other one the north; some of the records of the ostrich in the Najd plateau that include Al Qasim, connects these two populations and could be defined as possible corridor. From the interviews in the Al Qasim areas, old people mentioned there might be some resident populations of ostriches there, but these are mainly migratory birds which they used to see and hunt (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Location of Eggshells, shown in large red bullets; collected from 2007 to 2016; the possible corridor and green small dots are records from Jennings [9], while big green dots depict eggshells of Red-necked Ostrich which were collected for comparison in Mahazat as-Sayd PA.

Size measurements of complete eggs: A total of seven complete eggshells were found in Empty Quarter and they were measured. Three are kept in Najran Museum and four are kept with the author. The average length of the Arabian Ostrich egg was 139mm and width is 113mm, while 9 complete eggshells of the Red-necked Ostrich were also measured and the average length is 149mm and width is 122mm.

Conservation issues: The widespread introduction of firearms and, later, motor vehicles marked the start of the decline towards extinction of this subspecies. Earlier, hunting with bow, arrows and horses had allowed most animals of a group to escape, but rifles enabled the poachers to shoot down many individuals for the sheer fun of it. Hunting in 1920s and 1930s could be the key cause of decline and extinction of the species, especially for plumes, which were always popular and reached a fashionable peak in the western world at the beginning of 20thcentury. Vesey-Fitzgerald (1950-52) attributes a “big massacre” in1930s to the demand for plumes.

The Red-necked Ostrich is introduced into areas once occupied by the now extinct Arabian Ostrich. For example, in April-May 2017, a total of 25 birds were re-introduced in UruqBaniMa’arid PA, and in 2016 a group of 15 birds were released in Shaybah Biodiversity Area in the Empty Quarter. The Red-necked Ostrich was chosen as a substitute because of its geographic proximity, phenotypic similarity, and conservation value.20,29 The population of Red-necked Ostrich in Mahazat as-Sayd PA in central Saudi Arabia is around 300.

We want to acknowledge many people including Ebin Khashan in Empty Quarter, Bander al Tamimi in Qasim and Sheikh Sulaiman al Hawi in Tabarjal and wildlife rangers in Empty Quarter, Naif bin Mashal al Utaibi who helped us in collecting eggshells in various parts of Saudi Arabia and Librarian of PSFWRC who helped us in literature review. We want to thank Saudi Wildlife Authority that permitted us to send samples to Oxford University for C14 dating analysis, especially to Dr. Peter Ditchfield, & Prof. Christopher Ramsey. We are also thankful to the reviewer of the manuscript, whose comments improved the paper.

Author declares there is no conflict of interest in publishing the article.

©2018 Boug, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.