Advances in

eISSN: 2377-4290

Case Report Volume 10 Issue 4

1Chicago College of Optometry, Midwestern University, USA

1Chicago College of Optometry, Midwestern University, USA

Correspondence: Jeanie C Lucy, Chicago College of Optometry, Midwestern University, USA, Tel 630 960-3928, Fax 630 960-3033, Tel 630 960-3928, Fax 630 960-3033

Received: June 12, 2020 | Published: July 23, 2020

Citation: Lucy JC. Secondary open-angle glaucoma in presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Adv Ophthalmol Vis Syst. 2020;10(4):74?77. DOI: 10.15406/aovs.2020.10.00389

Purpose: Secondary glaucoma refers to any form of glaucoma in which there is an identifiable cause of increased eye pressure, resulting in optic nerve damage and vision loss. Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS) is an infection caused by the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. There are diverse ocular and systemic manifestations of POHS, ranging from influenza-like illness, cavitary lung disease to life threatening dissemination affecting multiple major organ systems. Once considered to be a public health threat mainly to Ohio, Mississippi River valley areas of the United States and South America, this case represents a new epidemiological report.

Results: Initial presentation of a young patient to our clinical service revealed several punched-out-chorioretinal lesions evident in the left eye. Secondary glaucoma was diagnosed in the left eye after Avastin injection to treat a choroidal neovascular membrane secondary to histoplasmosis. The patient was treated successfully with a topical simbrinza for the glaucoma.

Conclusion: The clinical presentation of histo-spots, peripapillary atrophy, and choroidal neovascularization represents a confirmed triad for POHS. Choroidal neovascular membranes can be a complication of POHS and anti-VEGF is a standard treatment. Certain anti-VEGF injections have been linked to sustained elevated intraocular pressure. From a public health perspective, we can look for POHS in other areas of the world where it is not usually and customarily found as well as monitor patients for prolonged increase in eye pressure after Avastin injection.

Keywords: secondary open angle glaucoma, presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome, turkey, avastin, public health

Worldwide the number of people with glaucoma is expected to rise from 64 million to 76 million in 2020 and 111 million in 2040, with Africa and Asia being affected more heavily than the rest of the world.1,2 The most common type of glaucoma is still primary open angle. The highest prevalence of Primary Open Angle Glaucoma (POAG) are in African countries.1 This is not surprising since the increased risk of glaucoma among people of African descent has been widely accepted for many years.3,4 Prevalence of glaucoma is difficult to pinpoint due to differences in how it is defined, and diagnostic equipment. Worldwide estimates in 2014 of POAG prevalence among people aged 40-80 years showed estimates of 2.31% in Asia, 3.65% in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 4.20% in Africa.1 If diagnosed early, primary glaucomas are managed by early diagnosis and treatment.

Secondary glaucomas have not been studied as widely as POAG. They differ from POAG by the fact that they are often a result of a positive history and ocular findings of pathologies such as trauma, previous surgery, neovascularization, inflammation, and other abnormal ocular or systemic findings that could have caused prior or current IOP elevation. In addition, patients with unilateral glaucoma are often suspect for secondary glaucoma if the other eye has no evidence of a primary glaucoma. In a study by Gadia in 2008, it was found that common causes of secondary glaucoma included post vitrectomy surgery (14%), trauma (13%), corneal pathology (12%), aphakia (11%), neovascular glaucoma (10%), pseudophakia (10%), steroid-induced glaucoma (8%), uveitic glaucoma (8%), and miscellaneous causes (14%).5 When cause were broken down by age: the most common cause for those 0-20 years old was trauma (often sports-related); for patients 21-40, post-vitreoretinal surgery was most common; neovascular glaucoma was most common in those 41-60 and pseudophakic glaucoma was most common in those over 60 years of age.5

In some cases, if the primary pathology is treated properly and the possibility of secondary glaucoma is kept in mind, triggers leading to secondary glaucomatous damage can be prevented. Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS) was first described in 1959 by Woods and Wahlen as peripheral chorioretinal scar and hemorrhagic macular disciform lesion in a patient with positive histoplasmin skin test.6 POHS is an infection caused by a fungus called Histoplasma. The fungus lives in the environment, particularly in soil that contains large amounts of bird or bat droppings. In the United States, Histoplasma mainly lives in the central and eastern states, especially areas around the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. The fungus also lives in parts of Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and Australia.7 While POHS infection can be found all over the world, very few cases have been found in Turkey which is where this case is from.

POHS is accepted as an entity characterized by small, round, discrete, atrophic mid-peripheral chorioretinal lesions (called histo spots), peripapillary atrophy, and choroidal neovascularization (CNV).8 Patients do not exhibit anterior segment or vitreous inflammation. Diagnosis is based on typical clinical findings, as well as history of exposure to the pathogen such as residence in an endemic area for Histoplasma capsulatum.9 A major cause of vision loss associated with POHS are macular CNV and formation of disciform scar. Treatment with anti-VEGF aims to minimize the area of scarring and thus reduce the size of the scotoma. This study represents a case of CNV secondary to POHS treated with Avastin which caused a secondary glaucoma.

A 25-year-old Turkish male presented to our clinic for the first time after arriving in the USA one week prior with complaints of blurry vision in the left eye which was first noticed twelve months ago while living in Turkey. A detailed history revealed that the patient had not traveled to other countries other than Turkey and the United States. He was diagnosed one year prior with POHS that was treated with an unknown anti-VEGF in Turkey. Refractive error was Plano in both eyes with best visual acuity of 20/20 in the right and 20/400 in the left eye. Anterior segment examination was within normal limits. Intraocular pressures measured by Goldmann applanation tonometry were 12 mmHg in the right eye and 12 mmHg in the left eye. There was no sign of inflammation and no signs of secondary glaucoma from pigment dispersion, or pseudoexfoliation. Prior to this incident, ocular and medical history were reported as unremarkable based on previous records from well care examination in Turkey two years prior. There was no history of glaucoma in the patient or his family, or trauma and no history of steroid use.

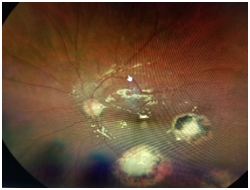

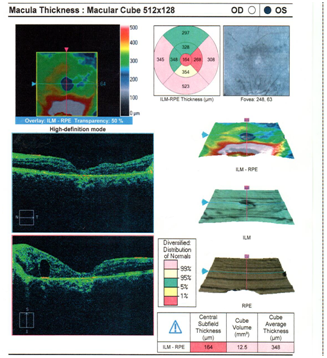

Dilated fundus examination revealed that the right eye was unremarkable, yet the left eye showed several punched-out-chorioretinal lesions with macular involvement (Figures 1&2). The OCT (Figures 3&4) depicts a normal right eye with abnormal left eye showing macular edema precipitated by vascular damage, ischemia, and inflammation leading to blood-retinal barrier breakdown and impaired fluid filtration from the POHS. The OCT also shows macula edema and a neovascular membrane of the left eye. Due to the current findings, the retina referral was initiated with confirmation of the diagnosis of POHS with treatment of Avastin (bevacizumab)1.2 mg. Three months post-op, best visual acuity in the left eye was 20/70 and the primary condition of POHS was stable yet intraocular pressure was present at 35mm Hg in the left eye. The right eye was within normal limits and had a intraocular pressure (IOP) of 12mm Hg. Cup to disc ratios were recorded at 0.25/0.25 in the right eye and 0.75/0.75 in the left eye. The visual field confirmed optic nerve damage and a superior arcuate scotoma (Figure 5). The patient was treated with simbrinza 1%/0.2% two times per day in the left eye. After two weeks the pressure was stabilized at 15mm Hg in the left eye with right eye pressures remaining unchanged.

Figure 2 The left eye (OS) shows several punched-out-chorioretinal lesions with macular involvement.

Figure 4 OS OCT

Normal right eye with abnormal left eye showing macular edema precipitated by vascular damage, ischemia, and inflammation leading to blood-retinal barrier breakdown and impaired fluid filtration from the POHS. The OCT also shows macula edema and a neovascular membrane of the left eye.

Two major issues arose in this case including POHS in a young male from an area where this infection is not commonly found and secondly, the issue of how the diagnosis of POHS has affected the development of secondary glaucoma. Injecting anything in the eye raises IOP which has been well documented in the literature with pressures going as high as 90mmHg with a standard volume of anti-VEGF medication.10 Most healthy eyes can sustain any pressure in a manner which is short lived. However, IOP stays chronically high after anti-VEGF injection in some patients for unknown reasons.11 Patients with glaucoma can have trouble with increased eye pressure after injection, yet this patient experienced sustained pressure without being previously diagnosed with glaucoma after the POHS diagnosis. Central USA is well documented as having the greatest prevalence of histoplasmosis.12 Prevalence may increase with international travel and the use of immunosuppressants.13‒16 Evidence based research regarding worldwide distribution of histoplasmosis and soil isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum lacks sufficient data. Cases of histoplasmosis found in Turkey also has a limited narrative. European studies have shown two cases between 1995 and 1999 in Turkey that may have been autochthonous yet patients had no ocular symptoms.17 This may be one of only a minimum number of cases of diagnosed POHS which originated in Turkey.

Formal treatment guidelines for POHS currently do not exist. It is not believed that POHS represents an active infectious process so antifungal therapy is not indicated.18 Patient education regarding risk for vision changes due to CNV and self-monitoring is standard of care. Estimated prevalence regarding POHS with CNV complication is half a central old. Today there are still questions regarding whether POHS is truly caused by Histoplasma. Previous demographic findings show that females have POHS more than males, yet current data is changing in this area. This case involved a male patient and supports current data. When CNV is found, this one factor causes most patients to experience some degree of vision impairment.19 Progression timetables with POHS are not known. Understanding of progression to CNV in POHS may improve with close monitoring of retinal image patterns on optical coherence tomography (OCT). CNV usually develops between the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and the neurosensory retina, with imaging features comparable to those of classic type 2 diabetic CNVs.20‒22 Development of CNV has been associated with oxidative stress, hypoxia, and autophagy, yet the exact context in which it develops in POAG requires more research.23 When CNV is present, treatment with Anti-VEGF has been successful, yet secondary glaucoma may be at a higher risk than previously thought. Risk may be associated with degree of steroid response or degree of CNV progression.24

Located mainly on the Anatolian peninsula in Western Asia, Turkey is a transcontinental Eurasian country with a smaller portion on the Balkan peninsula in Southeastern Europe. Current studies indicate that histoplasmosis with POHS such as the one presented here do not have high prevalence in Turkey, especially in young males. Public health experts and primary care eye physicians need to be aware of histoplasmosis in patients living in and traveling to and from Turkey. POHS requires strict monitoring for early detection of potential CNV. Progression time table of POAG to CNV is still unknown so careful examination and use of OCT is beneficial. In this case Avastin was used to successful treat CNM secondary to POHS with post-operative elevation of intraocular pressure. Given the debilitating effects of glaucoma, secondary glaucoma requires just as much attention to mitigate complications and prevent blindness whenever possible.

None.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2020 Lucy, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.