Advances in

eISSN: 2377-4290

Case Report Volume 6 Issue 1

Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences Khoo Teck Puat Hospital Singapore

Correspondence: Sanjay Srinivasan Khoo Teck Puat Hospital 90 Yishun Central Singapore , Tel 6555 8000

Received: October 25, 2016 | Published: January 27, 2017

Citation: Chan T, Sanjay S (2017) A Peck of Affection or a Peck of Aggression: Case Report of an Eye Injury Due to the Black-Naped Oriole. Adv Ophthalmol Vis Syst 6(1): 00169. DOI: DOI: 10.15406/aovs.2017.06.00169

To highlight the potential dangers of Black–naped Orioles in urban Singapore. A patient encountered the wild Black–naped Oriole in his backyard and attempted to tame the bird. The bird attacked the patient and caused injury to the eye. He presented to the Accident and Emergency department with a corneal epithelial defect in the left eye. The injured eye was treated with topical antibiotics and lubricants, subsequently recovering without any long–term sequelae.

Keywords: black–naped oriole, Singapore, corneal epithelial defect, ocular trauma, bird

Black–naped Orioles are distinctive black and golden–yellow medium–sized birds with a pinkish bill. They are known to breed in Singapore frequently spotted in forest canopies, mangroves, and cultivated urban landscapes such as gardens, parks, and residential housing estates.1,2

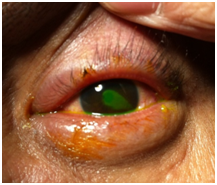

A 49 year old Chinese male was in his backyard when he heard the lilting and fluid call of a nearby bird. Investigating the sound, he chanced upon a juvenile Black–naped Oriole (Figure 1). In his attempt to examine the bird, the bird’s bill attacked the patient’s left eye causing severe pain and tearing. The pain persisted and he presented for consultation at the Accident and Emergency Department. On initial examination, unaided visual acuity was 6/6 in the right eye and 6/18 in the left eye (Figure 2). The left eye showed a 5.6 x 3mm corneal epithelial defect with conjunctival injection, while the fellow eye was normal. The anterior chamber was deep and quiet with a normal intraocular pressure in both eyes.

Figure 2 The patient’s left eye at presentation. Fluorescein stain showing a corneal epithelial defect.

Dilated fundus examination was unremarkable bilaterally. His left eye was treated with moxifloxacin 0.5% eye drops four times a day, atropine sulphate 1% eye drops twice daily, preservative free lubricants hourly with vidisic™ gel once every night. He was given oral paracetamol 500mg and codeine phosphate 30mg and an IM tetanus toxoid injection 0.5mL by the emergency department. A day after the injury, his left eye visual acuity was 6/24 with pinhole correction of 6/7.5. The corneal abrasion had resolved completely but the tear film was unstable showing a decreased tear break up time less than 10 seconds. Moxifloxacin and atropine was discontinued, while preservative free lubricants were continued. On follow–up one week later visual acuity in the left eye was 6/9 (Figure 3). The pupil still had partial residual effects of atropine. Subsequently patient was lost to follow–up.

Ocular trauma resulting from bird attacks is rare in medical literature but not necessarily uncommon.3 The incidence of such injuries still remains unknown. Previous literature has showed examples of eye injuries caused by wild birds like the common myna,4 sparrows,5 owls,6,7 and even an ostrich.8 Many of these injuries resulted in severe ocular trauma requiring surgery. Domestic birds such as roosters and hens have also been reported as culprits of serious eye injuries, like a ruptured globe in a 2 year old girl9 and penetrating injury resulting in uniocular blindness in a six year old boy.10 Bird attacks can occur even without provocation as seen in a case series of attacks on joggers passing by.11 A recent study conducted by the National University of Singapore suggests that the current population density of the Black–naped Oriole is approximately 0.119 birds per hectare. To put it into perspective, urban areas in Singapore such as Hougang (13.93km2) and Yishun (21.24km2) will have approximately 166 birds and 253 birds respectively.12

This case report aims to highlight the potential dangers posed by common urban birds. When the bird species was narrowed down to the Black–naped Orioles, a literature review was done. However, it did not reveal any known zoonotic diseases transmitted by Black–naped Orioles or provide any information of the microorganisms that reside on the bird’s beak. The bird has been documented to feed on fruits, nectar, and insects. Known examples of common fruits include mango, banana, papaya, and star fruit. They have also been seen to feed on plant species like Acacia auriculariformis, Ptychospermamacarthurii, Cinnamonuminers, Pithecellobiumdulce, Azadirachtaindica, Morindacitrifolia, Syzygiumgrande, Ficus spp., Campnospermaauriculatum, Raphidophorakorthalsii, Gnetumgnemon, Macaranga spp., Vitex pubescens, and Passiflorafoetida. The orioles will feed on nectar from flowers such as the Erythrina variegata and Callistemon sp. Their diet of insects includes grasshoppers, alate termites, caterpillars, mantids, and pupae.12–14 There has been no research available that isolated specific microorganisms from the Black–napedorioles beaks.

However, there have been studies that showed Pseudomonas aeruginosa growing from laboratory cultures of grasshoppers.15 Microbiological specimens were not taken from the patient at the time of presentation as there were no signs of infection. However, as the possibility of a Pseudomonas infection cannot be ruled out, it would be prudent to cover bird–related ocular eye injuries with topical prophylactic antibiotics. Studies have shown the vast majority of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains are susceptible to ciprofloxacin (a fluoroquinolone).16 Using this information, the treatment plan for this patient included the use of a topical fluoroquinolone such as moxifloxacin, which was readily available in our hospital formulary.

Our patient was attacked by a Black-naped Oriole (Orioluschinensis), commonly found in Singapore and many parts of Asia. This case shows the importance of awareness among the public when encountering wild birds that have adapted to the urban setting. Although the microorganisms harboured in the Black-naped Oriole are not well-known, in our case the use of a fluoroquinolone eye drop was adequate enough for microbial coverage.

None.

None.

The authors declare that there was no conflicts of interest.

©2017 Chan, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.