eISSN: 2577-8250

Review Article Volume 4 Issue 6

Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica

Correspondence: Claire MarieDe Mezerville Lopez, Universidad of Costa Rica, USA

Received: December 15, 2020 | Published: December 31, 2020

Citation: Lopez CMDM. Restorative practices and their potential to foster resilient masculinities from patriarchal culture: a scoping review. Art Human Open Acc J. 2020;4(6):261-267. DOI: 10.15406/ahoaj.2020.04.00179

This paper explores how strength-based approaches and restorative practices can foster resilience from patriarchal masculinities in Latin American adolescent boys. Gender violence from the perspective of critical theory will be described. The need for community engagement and critical pedagogy approaches are explored in the context of Latin America. A case study will be developed and analyzed about a specific experience with an all-boys Costa Rican high school where efforts for a restorative initiative were unsuccessful. Implications for practitioners are developed through the description of intervention models from both resilience focused approaches and restorative practices.

Keywords: resilience, restorative practices, masculinities, adolescence, critical pedagogy

Adolescence is a sensitive period in which the construction of the individual’s identity ideally involves developing a sense of belonging, purpose and accountability. Adolescents in Latin America face many cultural demands related to traditional gender roles and patriarchal culture. Patriarchal culture is understood as institutionalized sexism,1 including the social expectations for boys to never show weakness, to withhold the expression of specific emotions, and an orientation towards domination and control.2 On this matter, patriarchal culture is also based on the belief that societies must be controlled through dominating forces and that domination is associated with masculinity.1,3–6

According to Costa Rica’s Ministerio de Educación MEP, Spanish for Ministry of Public Education, patriarchal culture is dangerous because it entails the belief that gender violence is inevitable or justifiable because is associated with the core and biological nature of masculinity in particular and humanity in.7 Interestingly, research shows that the new generations of adolescent boys question this social dominance orientation4 and are more open to challenging rigid gender roles, embracing the expression of emotion and the questioning of traditional stereotypes associated with violence.8,9

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Latin America as a region is going through significant cultural changes that question traditional gender roles.9 However, this process still faces several cultural barriers and obstacles. This paper will focus on how resilience-focused-interventions on masculinities can be offered through restorative practices as a preventive strength-based approach. Strength-based approaches are understood in this paper as opportunities to address issues from the perspective of the positive assets that communities, families and individuals can contribute, instead of basing only on the current deficits. It will be stated, however, that in structural, multifactorial and sensitive issues such as gender violence, these approaches will only work if they build from a transformational pedagogy of liberation3,10 that engages the whole community setting. Throughout this paper, a case study will be described of a public all-boys high school from Costa Rica with an attempt at a restorative approach regarding gender violence on a particular incident.11 The analysis of this case serves to contribute with the reflection of the possible needs within adolescents’ construction of positive identities to build a deeper sense of community and belonging, and active social engagement.

Gender theory and Latin American youth

Lethal violence against women in Latin America is on the rise.6 The negative impact of stereotyped gender roles on boys and men is also a subject of study and research: men are more likely to commit suicide, to take poor care of their own health and to engage in risky behaviors.1,2,9,12 The current social and political scenario witnesses a resurgence of dominating masculinities being romanticized by fundamentalist groups, seeking to return to a radical traditionalism.13,14 Reactive approaches from justice and education are probably not going to be enough to respond effectively to gender violence in these turbulent and polarized times.

A feminist approach to boyhood and manhood is also a topic of research and discussion. 1,5,9,15–17 Bassham18 asserts that feminism, as a philosophy, emerged in the nineteen seventies, as a branch of critical theory, crystallizing the contributions of feminist scholars from previous decades. Feminism can then be defined both as a social movement and a theory: Black et al.,19 define it as a movement for equal rights for men and women, as well as positive changes in society. As a branch of critical theory, feminist theoretical approaches embrace gender theory, coined by Sandra Bem in 1981.18 Gender theory explains how individuals are gendered in society and these traits are maintained and transmitted from one generation to the next through culture.5,19 Yet, individuals are not only gendered by culture. The concept of intersectionality was coined in 1989 by Kimberlé Crenshaw to explore how different aspects of a person’s identity, including race, age, education, disability, sexuality and, yes, gender, influence individuals and the impact of a culture.19 This impact is not only patriarchal but also capitalist, colonial and white supremacist.1 Strength-based approaches with a community and restorative focus can potentialize the valuable insights of gender theory in the midst of the current polarization.

Efforts to promote healthy masculinities that foster a culture of peace and relational community become relevant for the physical and mental health of both men and women. This paper will focus on exploring the topic of masculinity in adolescent males, in order to find out how restorative strategies can facilitate resilient masculinities within a patriarchal culture, so that is possible to help others understand why it is valuable for restorative practices to be implemented in Latin American schools as a strengths-based approach to healthy male development.

Krauskopf 20 explains how the school setting is the environment where adolescents experiment with their capacity to participate as citizens in a period of life where they are also building their own identity. Intergenerational relationships that develop within the school setting offer the opportunity to build a reflective and accountable sense of self in adolescence. About this topic, the ACQUIRE Project 2 developed a guideline mentioned before, about working with boys and schools on subjects related with gender equity. According to this source, boys in Latin America face several prejudices associated with the patriarchal culture, such as the following mandates of being a man (Table 1).

Mandates from Patriarchy about Being a Man |

|

Be tough |

Get pleasure from women |

Don’t cry |

Have children |

Be the family’s only provider |

Marry |

Keep control. Never back down |

Take risks |

Have sex any time you can |

Never ask for help |

Have sex with as many partners as you can |

Use violence to solve conflict |

Table 1 Mandates from Patriarchy about Being a Man

Masculinity is significant for boys. Oberst claim that adolescent boys that perceive themselves as masculine are associated with higher rates of wellbeing, whereas according to these authors, there is no significant relation between girls perceiving themselves as feminine and increasing their wellbeing. According to UNESCO21 boys are more likely to develop self-confidence earlier than girls.

On this matter, Aranda et al.,4 explored the assignment of male stereotypes and how this explains social dominance orientation (SDO) scores. In their research, SDO was not associated with sex, but with youth that held traditional stereotypes. Features related with traditional masculinity included independence, production, competitiveness, leadership, and achievement-oriented roles. These traits correlated with more sympathetic ideas about society functioning as a hierarchical organization. The authors go further to affirm that “the acceptance of hierarchical systems among high-status groups is a way to protect and maintain their privileged position compared to others”.4 These kinds of dynamics may contribute to maintaining patriarchy as institutionalized sexism1 and structural violence in general, defined by Weingarten (2003) as the aggressions that affect people “whose identities mark them as different from a hypothetical average or a cultural ideal” (Weingarten, 2003, p. 53).

On the latest Costa Rican periodic review about Human Rights, Costa Rican Congressman Enrique Sánchez claimed that Costa Rica’s greater challenge on this topic transcends normative changes, and approximates us to a reality “where violence against women has not been completely denaturalized and is an everyday issue: sexual harassment in public and private spaces, women that die at the hands of their partners and political violence” (United Nations, 2019, minute 18), and Sagot6 has affirmed that violence against women in Latin America is manifesting a lethal scalation. Costa Rica recently passed a bill against sexual harassment in the street22 that has been criticized by general public and legislative assembly representatives, due to the normalization of this kind of violence and the rejection of feminist initiatives.13,14,23

In that sense, a recent study developed in Costa Rica described youth’s perspectives on several issues, including conflict and violence. Morales, Chaves, Ramírez, Jiménez, Vargas, García & Yock, investigated a sample of 3074 high school students from Costa Rican coast provinces. Over 70% of the sample mentioned that in their everyday life, punching is a way to solve conflict; 12.5% of the sample has suffered some kind of aggression, with 61% of the aggressions being emotional abuse, followed by physical (34%) and sexual (24%). 28% of the adolescents that suffered some kind of aggression report that it was bullying that came from classmates or friends. Although access to education is equal in Costa Rica for both boys and girls, boys are more likely to drop out of school. Violence against women, starting in adolescence, is still a sensitive and unresolved issue in Costa Rica.

According to the Dirección de Vida Estudiantil DVE, heteronormative patriarchal systems are reinforced with social mechanisms such as marginalization, invisibility or persecution.7 According to Lustick23 restorative practices could become unintended accomplices of keeping the hegemonic status quo unless they are implemented with “a critical eye toward reversing the traditional notions of control and order” (p. 8). To promote resilience from violent masculinities, restorative practices need to confront the privilege associated with traditional masculinities through honest and engaging conversations with adolescent boys and with their relational leadership.

Costa Rican specialist in masculinities, Álvaro Campos, presented at the UNESCO Conference Vinculando a los Varones (Engaging Boys), describing the work of the Wëm Institute with several Costa Rican communities. Wëm is a word in Bribri, a Central American indigenous language, that means “man.” Wëm Institute’s work has included teachers, police officers, fishermen, informal workers, boys, elderly, and indigenous communities to prevent violence related with traditional masculinities. Their work relies on five principles: (1) the need to manifest in the public space; (2) men need to engage other men with language related with masculine codes; (3) engagement should be done through promoting prevention and positive models; (4) work should not rely on isolated activities from the institutional hierarchy, but on community and continuous processes; and (5) the necessity to engage men with the achievement of gender equality based on the explicit rejection of sexism and homophobia, and respect towards human rights and diversities.9 He asserts that:, It is about contributing to the construction of an alternative masculinity, of different masculine subjects, that are able to talk openly about their emotions, concerns, fears, experiences, weaknesses and insecurities in the context of gender equity (Campos, at UNESCO, 2016, p. 24).

Wëm is far from alone in these efforts: different organizations across Latin America explore this work: GENDES in Mexico, Glasswing International in Honduras and El Salvador, OYE in Honduras, Human Partner in Colombia, Fundación Cultura Salud Pontificia in Chile (Dunia Perdomo, personal communication, November 27th 2020), among many others. An alternative masculinity cannot be taught through a program-based curriculum only: these are the socializing experiences that school have to offer only through a critical, relational and community manner. There are reasons to be hopeful: several authors claim that Latin American adolescents in this decade are slowly separating themselves from the more traditional stereotypes and, for example, are more interested in one day becoming affectionate fathers.4,8,9 This transformation has to do with the desire to have meaningful and affectionate relationships,1 if not only towards women and peers, perhaps towards future offspring. It is for this reason that is important to engage boys in educational interventions that question the status quo, support transparent and engaging leadership, confront shame related with privilege in a way that communicates that they are capable and lovable,24 talks explicitly about the harms that patriarchy brings to everyone in the community, exalt the importance of relationships, and the healthy expression of emotions.

In his recent book Healing Resistance, Haga makes a description and analysis of Kingian-nonviolent activism from an autobiographical perspective. The author argues that nonviolence is the path to Dr. King's reference to “beloved community”. Nonviolence, with restorative justice as one of its methods, requires a principled approach, discipline, training and a commitment with social change. He refers to the importance of men working with men to question patriarchy: “Male-identified people shouldn’t be working to undo patriarchy because they want to protect women. We should be doing it because we understand that patriarchy rips apart a core of our own humanity.” (p. 115).

Resilience focused interventions: all about relationships

The focus of this section is to describe how resilience-focused-interventions in school settings have been explored in research, in order to conceptualize them in relation to restorative practices. Regarding the external factors related with this phenomenon, according to Pitzer and Skinner25 the external dynamics that foster resilience in students depend on the interpersonal resources that teachers have. These authors describe the need for teachers to offer warmth instead of rejection, structure instead of chaos, and autonomy support instead of coercion.25 Through these resources, they will be able to appraise relatedness, competence and autonomy, and this dynamic, in turn, generates the emotional skills in students that nurtures motivational resilience. For these authors, motivational resilience is understood as engagement, coping and capacity for re-engagement. The role of teachers on the development of these motivational interactions is crucial to foster resilience in the school setting.

Allen, Rosas-Lee, Ortega, Hang, Pergament & Pratt26 developed a qualitative study on positive youth development promoted by educators and youth leaders. The work on resilience from patriarchal masculinities with a restorative approach must begin by engaging youth in critical and relational conversations with teachers and community identified leadership, trusting on a common goal: a strength-based support towards positive youth development. To confront patriarchal values means to have restorative experiences where teachers and youth leaders can explore, along with people that have experienced the adversity of patriarchy in a more direct manner, ways to understand the depths of the harm, to repair some of it and to restore a sense of community.27 This process is often complex, longitudinal and uncomfortable.1 However, if there is relational safety to engage and train youth in Nonviolent Communication, to foster active listening and to express honest opinions, it will be possible to collectively reconstruct what can be understood as healthy masculinities, built from the adolescent’s language and codes.

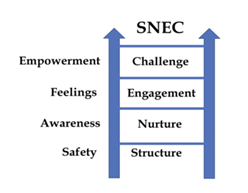

On this topic, the Relational Care Ladder28 is an applicable model that illustrates the above. It is a model dependent on the active establishing of structure and boundaries. Although Rundell28 develops this model as a way to intervene with youth that have experienced trauma, it is useful to consider it as part of building a restorative culture based on critical and transformational pedagogies. This model can guide the work with teachers and youth leaders to empower them to also follow it on their conversations with adolescent boys. Nurturing conversations that foster awareness about the student’s rights and responsibilities are fundamental. Teachers engage the learning community in a social and emotional way by incorporating feelings in ways that are horizontal.29 Expression of feelings is encouraged through engagement and teachers empower youth by challenging the person to take actions. This is illustrated through the acronym SNEC (Structure, Nurture, Engagement, Challenge) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Relational Care Ladder. Co-creating change within a traumatized child & family. IIRP World Conference Strengthening the Spirit of Community: IIRP & Black Family Development.

The strength-based process takes place in the context of strong relationships and an awakening of a sense of community, co-responsibility and belonging. Restorative practices can be practical means to promote engagement, critical and transformational thinking in order to challenge adolescents towards growth. Most of all, these are practices that can build a sense of intergenerational community, necessary to address issues such as masculinities resilient from patriarchy.

Resilience and the steeling effect

For this paper, “resilience” will be understood as the capability to overcome adversity and develop personal growth in the midst of challenges. The steeling effect will refer to the opportunity Latin American boys have to respond to challenges in a way that they grow and actively contribute to the community. Healthy masculinities are resilient, strength-based and relational self-constructions. They step away from the traditional conceptions of strength, domination and control, and move towards a value focused and interdependent construction of self, that focuses on their affective responsibility for self and community, and on the development of positive assets, instead of fixing on personal deficits.

Vanistendael30 defines resilience as both resistance to human destruction and as the capacity to build positive human behavior despite difficult circumstances. Rutter31 refers to the “steeling” effects of resilience when he notes that exposure to adversities may “either increase vulnerabilities through a sensitization effect or decrease vulnerabilities through a steeling effect” (p. 337). Perry & Szalavitz32 argue that, if stress in the environment is unpredictable, severe and prolonged, it will cause vulnerability, whereas if stress is predictable, moderate and controlled, it will generate resilience. Taleb mentions that eliminating stress altogether is not the way towards resilience. Quite on the contrary, he claims that overprotection fragilizes individuals: “If about everything top- down fragilizes and blocks antifragility and growth, everything bottom- up thrives under the right amount of stress and disorder”. Predictable and controlled stressful situations within a supporting environment will foster resilience so that individuals not only endure but thrive. It is not possible to shield adolescent boys from patriarchal culture altogether, but it is possible to foster relational environments that engage them and empower them to learn, participate and encourage a resilient and critical reflection about patriarchy. These processes moderate patriarchal culture and offer alternatives for resilience.

Restorative practices

Restorative practices were defined by the U.S. Department of Education as “non-punitive disciplinary responses that focus on repairing harm done to relationships and people, developing solutions by engaging all persons affected by harm, and accountability”.33 They are based on a model oriented to the importance of strengthening community and building social capital through restoring human relationships and repairing harm when it occurs.34 Restorative practices in schools are based on the grounds of high participation from students and all members of the community, transparency and engagement from leadership, and on responses that work with people by exalting both high support and high accountability.

Díaz & Sime35 did a meta study about Latin American school practices and student coexistence. Seven main topics were identified: school violence, punitive regulations, skills development, conflict, communication-climate, bullying and school diversity. The authors mention a lack of research development on subjects such as gender issues, and interculturality in Latin America. They mention how Latin American research on school coexistence has been limited to descriptions about conventional responses to conflict, instead of developing innovative proposals on intervention programs (Díaz & Sime, 2016).35 On this topic, according to Gregory & Clawson36 affective interventions and restorative practices implementation in schools correlate with less misconduct from students, but gender and ethnic disparities persisted. Restorative practices as a way to enact a transformational pedagogical culture must draw back on its roots of a holistic, participatory restorative justice.

Restorative Practices as Means for Resilience Focused Interventions

Restorative practices can foster resilient environments. Henderson & Milstein37 offer a model of how to build resilience and how to mitigate risk factors in the environment (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Resiliency Wheel. Resiliency in schools: Making it happen for students and educators. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

According to these authors, in order to build resilience in the environment it is necessary to provide care and support; set and communicate high expectations; and provide opportunities for meaningful participation. To challenge cultural and structural factors that perpetuate gender violence requires community longitudinal interventions that sets the platform for community leaders to become engaged, participate in restorative processes and develop action plans with the youth they already have strong relationships with.

This will work, however, with approaches that are long-term, whole-school, and built upon experienced approaches on specific social issues, such as Wëm’s.9 As Lustick23 established, fostering strong interpersonal relationships through restorative practices is an important first step to process gender violence from the perspective of adolescent boys, and to confront their own biases in an environment of awareness, expression of emotions, empowerment and accountability. Restorative practices offer valuable and practical strategies for teachers and youth leaders that, in order to foster resilience in the environment, still need some tools to address difficult conversations. Not one single intervention will be enough, yet for restorative practices to become an effective manifestation of critical pedagogies, longitudinal approaches will need to become the norm.

An attempt of a restorative approach: a case study

With permission from Costa Rica’s Ministry of Education, the following experience will be described based on news reports, and the internal reports facilitated by the institution.11,38,40 In September 2019, the city of San José chose the Colegio Superior de Señoritas, Costa Rica’s historic Women’s Public Highschool, to close the Independence Day parade taking place on September 15th. This old historic educational institution is physically located across the street from Costa Rica’s historic Liceo de Costa Rica, an all-boys public high school, which is also a longstanding Costa Rican institution. During the parade, alumni—not current students—from Liceo de Costa Rica harassed and attacked the female students closing the parade, inflicting physical, verbal, psychological and symbolic aggressions.38 There were no judicial consequences for the perpetrators. Costa Rica’s Instituto Nacional de la Mujer INAMU, Spanish for Women’s National Institute, required an institutional response to these acts of violence. Therefore, the Minister of Education asked the Dirección de Vida Estudiantil DVE, Spanish for Direction for Student’s Life, a branch from Ministry of Education, to do an intervention with the younger students from Liceo de Costa Rica concerning gender violence, to sensitize them to the harm that was perpetrated by alumni from their very school.11,39 The intervention was proposed in explicit communication with the principal from Liceo de Costa Rica.39 and staff from MEP’s headquarters received training to facilitate it in the form of several workshops to cover all groups of seventh to tenth graders. The activity was designed and was meant to follow this agenda:40

On the date of the event, MEP personnel arrived at Liceo de Costa Rica, to find that there was a very low attendance from students and possibly there were problems with the announcement of the activity. Staff from DVE inquired with Liceo de Costa Rica’s staff about the lack of participation from students: both staff became defensive and had an argument about who was to blame for students not showing up. The activity was cancelled. The events of that day were systematized by DVE staff in a report sent to supervisory instances from the Ministry of Education.11

It cannot be stated that a restorative approach with students was unsuccessful, since it didn’t take place, but even if it did, there are several concerning issues to be addressed in this situation. The reason to cancel was that students did not show up: it could be argued that students did not participate as a rejection of the initiative. It could also be said that there was resistance from the school staff that wasn’t interested in the activity. It could also be argued that DVE’s strategy was not restorative in the first place, although it included restorative methods and development of affective skills: it was an adult-centered initiative that was led by people external to the community in question.

Can restorative practices function “top-down”?

It can be asserted that to have an honest conversation about an incident that involves shame and privilege is always difficult. The staff from the DVE have received training in restorative practices41 and designed the activity proposing a circle format oriented to exploring harm and building a sense of community. Restorative practices have been studied as interventions to reduce violence in schools,42,29 however, they have also been questioned as means that could maintain hegemonic systems by “keeping the order” instead of questioning and restoring the systems that underlie behavior.23 In this case study, the restorative initiative was a reaction to respond to a mediatic violent incident with boys that were not the perpetrators. Although it was asserted that the initiative was a preventive strategy with the Liceo’s younger students, the context wasn’t one of a longitudinal community approach based on critical theory, but a top-down reactive measure from the DVE: a centralized authority figure.

A one-time initiative by authorities that are external from the community are unlikely to create sustainable change. Motivational resilience25 sustained by teachers, community identified leaders and youth itself 26,5 is essential. These teachers, leaders and youth may very well be unwilling to question patriarchal culture and reluctant to issues related with gender equity, however, in the sight of harm, a collaborative and integrated creation of relational and safe spaces for active listening28 can lead to the critical conversations3,10 that allow youth to develop awareness and resilience in regard to violence and patriarchal culture. This community approach needs to begin with restorative dialogues between DVE and Liceo’s staff; between the boys, their families and volunteers from the Colegio Superior de Señoritas. The reactive focus based on punishment and control can evolve into a critical focus based on a resilience and strength-based approach towards positive youth development. Given the support and empowerment that they need, boys can become key players in building a culture for peace based on the committed construction of healthy masculinities.

Implications for Practitioners

Resilience-focused-interventions are based on fostering external factors that depend on practitioners who are prepared to address difficult issues in a direct and brave manner, and their capacity to foster an environment that is safe, engaging, and challenging. Personal and professional growth becomes an important task for teachers and other adults, who must begin by challenging themselves to construct positive and safe environments ready to manifest explicitly against patriarchal culture. These are the first groups that need to go through restorative processes of sensitizing, active listening, and critical problematizing of structural violence.24,27 Restorative practices offer ways to begin this path. Fostering resilience in the classroom is based on building strong relationships with the students. According to Perry & Zsalavitz (...) If we don’t give children time to learn about how to be with others, to connect, to deal with conflict, and to negotiate complex social hierarchies, those areas of their brains will be underdeveloped. As Hrdy (sic.) states: “One of the things we know about empathy is that the potential is expressed only under certain rearing conditions.” If you don’t provide these conditions through a caring, vibrant social network, it won’t fully emerge.

Resilience-focused-interventions through restorative practices offer ways to work on the five principles described by Campos on Wëm’s experience (as cited by UNESCO, 2016),9 regarding the construction of positive masculinities, only if the issues related with gender violence are addressed directly: (1) the need to manifest in the public space, through active engagement and meaningful participation; (2) men need to engage other men with language related to masculine codes, due to the relevance of a sense of connection and belonging; (3) engagement should be done through promoting prevention and positive models, through motivational resilience and based on high accountability and high support; (4) work should not rely on isolated activities from the institutional hierarchy, but on community and continuous processes; and (5) the necessity to engage men with the achievement of gender equality, based on the explicit rejection of violence, through the SNEC model of Safety, Nurturing, Engagement and Challenge. Resilient masculinities encouraged through restorative environments address strength-based healthy masculinities in Latin American adolescents. As Lustick23 mentions, teachers and administrators need to become aware of their own biases, connecting with students to open spaces to approach difficult subjects, as part of the social commitment that every school holds within a larger community.42–52

Teachers in Costa Rica are currently encouraged by the Ministry of Education through several protocols to foster a Culture of Peace and to promote student leadership.43 Restorative principles offer a conceptual framework and a practical model to develop resilience-focused-interventions, as described by Allen et al.,26 through authoritative/restorative classroom management, and as stated before, they align to the Resiliency Wheel as described by Henderson and Milstein.37 Yet, they could become apparent good practices that keep an appearance of harmony and order, while they avoid addressing the underlying causes of violence and harm.

Latin America is a region where being a boy is both a privileged opportunity for a less vulnerable stage of development, but also a challenge to break from patriarchal stereotypes that undermine deep human connection, which is necessary for wellbeing and for compassionate and responsible engagement with social realities. The understanding of community approaches based on critical pedagogy through restorative practices that incorporate resilience as a concept that is approached from a strengths-based perspective, is fundamental when working with youth from this generation; youth that should not merely endure negative messages or avoid bad behaviors, but who can learn, adapt and thrive with humanity and vision, becoming active challengers of their social realities as they dive into the uncertainties of the twenty-first century.

None.

Author declare that there is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2020 Lopez. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.