eISSN: 2577-8250

Research Article Volume 1 Issue 2

University of Science and Art, Rasht Branch, Iran

Correspondence: Minoo Khakpour, University of Science and Art, Rasht Branch, Iran, Tel 0098?9111362561

Received: September 20, 2017 | Published: October 16, 2017

Citation: Khakpour M. Aghadar, a belief of revering trees in gilan. Art Human Open Acc J. 2017;1(2):63-70. DOI: 10.15406/ahoaj.2017.01.00010

The effect of social systems and religious values which are tied up with graphical conditions on the mindset of the different tribes is well established. On this account, it is not surprising that the beliefs of herdsmen are different from the myths of farmers. Such a conflict can be found between the beliefs of plain-dwellers and the beliefs of mountain inhabitants. Thus, the diversity in myths, beliefs, and livelihoods among different ethnic groups is very common in a geographical area with a diverse climate. There is an urgent call for studying ancient beliefs of the rural peoples as such beliefs are at the risk of being vanished. The reason is that many villagers have chosen to live in urban areas for economic and welfare reasons or their lifestyle have been exposed to fast-paced cultural dynamics. Despite the frequent call, our knowledge about the source of the deep-seated beliefs is very limited. Less research exists on how such beliefs and mindsets have influenced the structure of habits and shrines. To address the gaps, this study examines the beliefs of revering different trees species held by plain-dwellers of Gilan who are endowed with diverse vegetation and explains how belief in such endowments are bound up with the structure of habitats and sacred places. Data for the present study were collected through observations and documents and analyzed using qualitative content analysis. The findings of the research can be used by architect designers, researchers from the variety of disciplines (e.g. archaeology), and policymakers to improve people’s lifestyles based on their culture and create culture- based habitats.

Keywords: sacred tree, gilan, aghadar, tomb, pilgrimage

Rituals as a major factor influencing different aspects of human life including birth, growth, livelihood, marriage, death and even the life after death have long been rooted in the cultural traditions of different ethnic groups. In ancient times, humans believed that all living things have humanistic souls and spirits. Through the civilizing process, semi-civilized humans started believing in the differentiation between the tree as a living being in nature and its mythological forms so much so that the humans attributed it wisdom and thought and even a holy spirit. In fulfilling their needs for shelter, birth, an abundance of aliment, they depicted it as a powerful entity, clung to it. They adhered to some specific rites of worship in a frame of time and place.

Recently, different aspects of rituals have received a widespread attention. The developments of new lifestyles and fast-paced cultural dynamics over time have brought about quantitative and qualitative changes in ecological and behavioral codes of the tribes. These widespread changes have led to the elimination of cultural diversity and have put the subcultures at the risk of destruction, thereby affecting the texture of larger communities. Though necessity of preserving the rites have been the subject of debate and attracted the attention of scholars in different, rarely such believes have been documented. Due to high attrition rates of village dwellers in Gilan, some of the rural rites of this area are being faded away. Though the rites of sacred trees have been extensively investigated, so far no research has been conducted in the geographical area of Gilan.

The essay is an attempt to show how rituals and myths have been conceptualized and differentiated. It also shows how the beliefs of the people around the world, different tribes and ancient Iranian have influenced the conceptualization of tree and its associated connotations. More specifically, this article examines the mindset and belief of respecting tree as a being with a soul in Gilan. In addition, it explains where this belief comes from and how the rites of revering the sacred trees have influenced the structure of buildings, especially habitats and shrines.

Theoretical foundation

This paper draws upon Eliade's theory which argues that a myth is a true history or what occurred at the beginning of time, and one which presents the pattern for human behavior. This theory posits that here is a close affinity between the myths and the rituals of mankind. According to Eliade, by attributing the word sacred and profane to location and time by religious man, he creates a boundary between these two concepts.

The sacred is s a dichotomy of profane. The scared can manifest itself to pious man as anything such as a tree. These objects become the focus of religious reverence because they are hierophanies. According to Eliade, the threshold is very influential in determining the form and type of rituals. Eliade defines threshold as a place where the two worlds are separated and also opposed, but at the same time where the worlds are connected, where passing from the profane world to the sacred world becomes probable. The sacred place implies a hierophany that results in separating an area from the surrounding cosmic environment and making it different in quality. Such interpretation seems to be deeply associated with the social structures and the biological practices of the peoples, which themselves are bound up with the geographic environment (pp, 115-117).

Tree - symbol

The tree is a vibrant, dynamic combination of three elements, sky, earth, and water. Tree has roots in the depths of the earth - in the center of the world - and grows in a time frame. As it grows, a ring is added to its trunk, its branches reach the sky. "The evergreen tree represents the eternal life, the immortality of the soul, and a tree with falling leaves symbolizes the world experiencing a renewed life and a continuous regeneration, from the death to life; resurrection, rebirth and the life itself. Both symbols reflect a plurality in unity. Lateral roots extending from the main root in the form of fruit seeds reunite with one another in every branch. The cosmic tree is then depicted as a cosmic tree whose branches are a divider and at the same time fastening, or it has two trunks, a root and its branches are connected, these images symbolize the metaphysical world, moving from a plurality to unity and again reuniting and the unity of the earth and the sky. The tree as the center of the world represents mountains and pillars and all the axes. A tree like a grave, a mountain, a stone, and water per se symbolizes the entire universe, and a column, a wooden arrow, etc.1 It is believed that those trees and plants which are beneficial to mankind possess a soul which goes back to prehistoric times. It also symbolizes the universe and represents the source of fertility knowledge and an eternal life. Some examples of sacred trees in the mythology of different nations are: Fig trees in Egypt and India, Aspic trees in Scandinavia, Willow and Pine trees in China and Japan, Palm trees in Mesopotamia and Laurel trees in Greece (including the Oak tree was sacred to Zeus, Laurel tree to Apollo, Olive tree to Athena and the myrtle-tree to the Aphrodite tree).2 In the ancient beliefs, gods live mainly in a sacred tree, which lies on the border of our world and the mystic world. After death, the souls receive water and food from the gods. The importance and veneration of some types of trees refer to their association with some of the important events, such as sleeping an Imam or a leader in the shade of the tree.2 Therefore, it was assumed that such a tree is sacred and helps their wishes come true.

For those with some religious experience, all nature with its self-disclosure capability enjoys a cosmic sanctity. The man of ancient societies tends to live in the sacred or in close adjacency to sanctified objects. "Today's man finds it difficult to accept the fact that the sanctity manifests itself in stones or trees-but we realize that what is concerned is not reverence of the stone in itself and a cult of the tree. The sacred tree or the sacred stone are not worshiped as stone or tree; they are worshiped just because they represent something that is no longer stone or tree, but the sacred.3 Bahar believes: "This is not just the souls of the dead or the gods in trees that make them sacred. The primitive people realized that having this assumption that souls or gods manifest in trees, or equating the souls or the gods with the trees bring substantial benefits to humans. For example, trees have the power to make clouds rain, to make the sun shine, increase herds and help women with fertility and childbirth.4

Tree in the eyes of ancient Iranian

In Iran, the earliest images of trees were painted on pottery, beads, and stones. Elamian world (e.g.the Lorestan bronze, Marlik, Amlash, Ziwi) is full of plant images which are associated or inspired by trees. Though tree images were not uncommon during the Achaemenid and Parthian period, in the Sassanid period, the images received a special attention, and they manifested all ancient traditions from the Manichaean, Zoroastrian, and Mythra religions. Trees play a key role in Iranian traditions. For instance a tree which is presented by a Mandala (e.g. Shamse or Toranj) in Iranian carpets or in the wall decorations of the traditional oriental arts, symbolizes the association between the earth and the sky. During the Achaemenid and Sassanid period, the Cypress tree as the tree of life was revered, and the palm, fig, cedar, olive and plane trees were sacred. In the monotheistic religions, some fruit trees such as fig, olive, apple, grapes, and pomegranate trees are considered as heaven trees, and people hang a piece of cloth from its branches and it is believed that in doing so, their wishes will be met (Figure 1 & 2).

Usually, the tree of life is located between the images of two monks or priests or two mythical beasts who are their guardians. The access to a lifespan mystic elixir requires the branch of the tree or its fruit to be touched and whoever defeats the guardians would turn to be immortal and stay juvenile for the rest of his life. On a golden bowl found at Marlik area in Roudbar, the images of two standing goats are seen on the sides of the sacred Tree (probably a palm) (Figure 3). In another Golden cup found in the same area, the recurring patterns of two cows taking care of the scared tree are seen. Both containers date back to the first millennium BC (Figure 4).

On the sanctity of various types of trees in ancient Persian culture, Bahar states as such: "It is not only the magnificence, big size, and lifespan of an old plan tree that makes it sacred; it is its juvenility every year that makes it magical and praiseworthy. Every year, it sheds its skin off, and its shoots start shining bright green, and this annual juvenility, as the everlasting feature of Cedar, sanctifies it because preserving youthfulness which is one of the prerequisites for fertility symbolizes the eternal blessings and gifts from gods and spirits. From the book of the Shahriyarian rites in Iran, Bahar quotes from Samuel K.D as such: "The kings of the Pars continuously revered plane trees," he maintains that "In the court of Iran, there was a golden plane and a golden grapevine in the king’s bedroom, the plane tree was adorned with gems and the Persian were worshiping it. When Darius the Great was in Asia, he was given a plane tree and a golden grapevine tree, and when King Kheshayar went to the Greek war, he saw a huge plane tree and ordered to be adorned with golden ornaments and to be protected by his special armies. Apparently obtaining the golden tree in king’s bedroom meant ruling the kingdom3 and this is exactly what can be seen in ancient times in Nemi temple in Italy, and the tree in this temple was protected by a priest throughout the day until the late night, As long as the priest was able to protect it, nobody could touch it unless the priest’s blood was shed. These two reflect the old rites. It means that ruling and serving as a priest both meant to preserve greenery and blessing, and the main task of a king or priest, a terrestrial symbol of heavenly forces, was to preserve the blessings and richness in his homeland.4

Totem in Gilan

The Persian clan in Gilan, a small community which draws its main principles from the macro patriarchal system, believes in Totem.4 They believe that worshiping gods and masters of all kinds is in fact associated with animals and plants. The idea of Totem has received much attention in the rural life in Gilan, and nowadays this issue has been more or less important. In the mountainous areas of Gilan, a huge mountain with its sharp summits has attracted the attention of inhabitants and sanctified the site. On the top of this mountain, people have built places where they make a solemn vow and pray for their needs. Galesh,5 who moves his flocks from the winter quarters to the country, gives away the one –day milk of his livestock to these places. In so doing, he prevents his flocks to be afflicted with different diseases throughout the summer. During the summer, he slaughters a few of these animals and gives away his meat to the pilgrims or custodian of the shrines.6 As we get away from the mountains and enter the foothills and then the plain, we see that the plants cover the entire regions, and this is a place where trees enjoy a unique sanctity. The inhabitants of the area believe that the vegetation variety has brought the bliss of God. It is not surprising that the tree as a symbol of heavenly power which deserves revering has become a fixed mindset of this cohort of people.

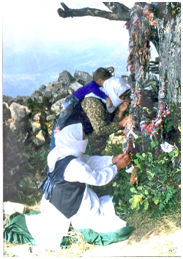

In Gilan, especially the plain areas, there is a common proverb which means: Wherever a large tree is, it is a pilgrimage of the Gilak. The large trees of the forest, such as planer trees and oak trees in the plain and aspic trees7 and different types of Cedars in the mountains are revered by the people. The people in this region believe that a tree has insight and wisdom. That might explain why people light candles and carry lanterns or seek help from trees by hanging something from its branches to cope with their problems. Like other sacred sites, trees should be revered. For example, villagers, including women and men, and sometimes women, collectively go on a pilgrimage on the special days of the year but this does not mean that the pilgrimage cannot be made individually if someone needs to make a vow for Allah or pray for his needs (Figure 5).

Types of trees and common names

People of Gilan believe that certain species of trees such as planer and oak symbolize the robustness and sanctity and pilgrimage. Boxwood tree is a symbol of greenery and sanctity.8 In the past, for the people in the northern part of Iran, the value and importance of the tree were so much so that the name of the trees or plants was used as the villages’ ornaments. Generally, the ways that this group of people name the villages is probably rooted in ancient Iran and selecting the names shows their great respect for some tree species such as Planer (Azad, Azadar), Boxwood (Kish), Oak (Mazo), Maple (Pellet), Elder (Lei, Lilaki), Pine or Cypress (Sor, Zarbin). Some of the chosen names for the villages which are derived from tree names are Azadlak, A'azbun, Kish Dareh, Kish Dibi, Kish Sara, Pellekeh, Mazobon, Sourjar, Sour Khani. There is a village in the rural region of Shab Khos Lat which is called "Sur Shafi Lot". In this name-the Yaw tree (sometimes Kish) is used with the suffix "Shafi"(i.e. intercessor). This tree was highly revered in the shrines and cemeteries of northern Iran. It seems that the people not only did venerate this tree but also pleaded it to intercede with God. The Evergreen tree which is long living has long been a symbol of life after death, and it is believed that that damaging the growing tree is ominous, because this tree is very resistant to the forces of evil.

It is noteworthy that the names of the above-mentioned villages are also derived from the name of the silk tree (Shab khosh). In general, if the tree is a symbol of grave, then it is called Pir (sagacious), Bozorgvar (magnanimous), Agha dar, Agha sur, Mazar, Agha rias and if it is a sacred stone, it is called Sang-e- Mazar (tombstone).5 Sometimes the tree itself has a special name. An example is Mir Hamza tree in Masouleh. This tree which has a masculine name is revered by the women in the village. Apparently, the prefix "Mir" in the name suggests that the tree is blessed and sanctified (Figure 6). It seems that the beliefs about worshipping have disappeared and transformed to interceding beliefs. In other words, the tree has already been eligible to satisfy the needs of the pilgrims, but with the advent of Islam, the worshiping practice of trees has turned into revering and pleading them to intercede with God.

Aghadar

"Perhaps sexual encoding is one of the important issues in the religious rituals and ceremonies of all nations." Different rites and practices underline this importance. Fertility rites which are common to various tribes lead to extensive encoding that does not need to appear in unobtrusive or bare forms and shapes. Attributing gender to non-living objects in the language is astonishing. In different languages, some objects are considered to be generally or preferably, male or female. Such attribution should be the result of common sexual encryption among different ethnic groups.6 Almost all the trees are considered as female, and apparently, the fruits are what trees are being compared share in common( Tertium comparationis). In Latin, assigning the female gender to trees is an absolute rule (women, trees, cities, lands, etc.). The sexual difference has long been important to human. The need for such assignment is not just limited to his beloved but involve whatever belongs to him. Human assigns a gender to everything around them " (ibid, 82) (Figure 7 & 8).

With respect to what has been discussed so far and the widespread belief in the futility of the tree in different cultures, using the term "Aghadar " with the prefix of "Agha " and assuming respected tree as a male is likely coincided with the birth or prevalence of this ritual at the time when the idea of patriarchy was dominant. Therefore, Aghadar is a totem representing a great respect for the believer- man. These trees are often renowned and reversed by women. This reverence seems to indicate a feminine decision; in other words, the women identify the holy trees with the characteristics of men and revered those (Figure 9 & 10). In some cases, in some areas of Gilan, including Lahijan, the trees that are left in the shrines and cemeteries are called Kish Khanam (Shamshad Khanum). Infertile women who wished to have a child used to put in a green cloth made hammock between two adjacent trees. These holy trees, which are reflecting purely feminine characteristics, are merely revered by women, and men were never allowed to visit them.

Sacred trees in the lives of the people

Once it was thought that the ground was flat, round and shaped like an overturned bowl, or a covered sky needed to be supported by a central pillar such as a mountain, a pillar, and a tree. The world's center or cosmic tree was known to the Babylonians and European peoples, and it was in Hindu mythology and was adapted from Buddhist rites.2

Cosmic symbolism can be found anywhere, and the symbolism that in most cases describes some religious behaviors in relation to the place where a person lives. In all traditional cultures, the habitation has a sacred aspect by the fact that it reflects the world. The house is an image of the world, and the sky is perceived as a huge tent supported by a central pillar. The tent pole or the central pillar of the house is likened to the pillars of the world and is so named. This central pillar has a significant ritual role.3

In the plain area of Gilan, generally using the trunk of trees in the pillar of residential buildings is quite common. This belief is popular with the villagers today. Given that trees are sacred for foresters, the use of sacred wooden columns to support the roof and strengthen the building is fully justified (Figure 11). In addition, symbolizing the pillar as a tree in the house underlines the central role of the cosmic tree in the world. This double-sided interpretation facilitates communication and, results in the convergence and unity with nature. Marashi in his history book entitled ‘Gilan and Daylamastan’ writes: "In Ranekouh they started a mosque whose pillars and wood blocks were ordered to be the pine wood from Sejiran (Eshkevar-Rūdsar), because the wood is durable and is similar to the granite stone.7 Generally, the coffins in Shrines are made of tree trunks. These trees not only reflect the belief in animism in ancient Gilan, but also show that the sanctification of trees in Gilan has occurred after Islam. It seems that as soon as Islam was introduced to some regions, some of the beliefs merged with religious beliefs and emerged in a new way.

Some sacred national and ancient elements of Iran such as light, earth, soil, and wind and other symbols of nature, have been mainly merged with some of the Shi'a beliefs, such as the attention to the Imams".8 Therefore, since the advent of a new religion, people have not abandoned the old beliefs at once, but they have slowly started merging them with new values. In the village of Karafestan, in Amlash district, a kind of planer tree has become a source of strong beliefs among in the villagers. The secretion of red sap from the bark of the tree in the first decades of Muharram has made the people believe that this is the way the tree shows sympathy with the mourning of those days. They carry some lanterns into the area and seek help from the tree by hanging something like a piece of cloth, put the sap on their heads and faces and they sometimes plead the tree to intercede with God though there is a holy shrine of Imam.

Sacred place

The sense created by place is of particular importance in determining the degree of sanctity. “Myriad rituals accompany transitory domestic threshold: a bow, a devout touch of the hand and so on. The religious significance of the threshold and the door is that they are symbols and, at the same time, vehicles for passing from one space to another. The threshold is a paradoxical place where the two worlds are separated and also opposed, but at the same time where the worlds are connected, where passing from the profane world to the sacred world becomes probable.9 The sacred place implies a hierophany, a forcible entry of the sacred that leads in separating an area from the surrounding cosmic environment and making it different in quality.3 In this way, every sacred place is a door for passing from one world to another. Therefore, the desire to create this sacred place highlights the necessity for creating this cosmic threshold. Sotoudeh in the book entitled from ‘Astara to Estarabad’ explains how the trees have converted to shrines over time. In last 50 years, almost ten trees which Rabino has referred to them as Mazar in his book called Gilan were nothing but some sturdy trees. Now some buildings have been made by these trees and named Imam Zadeh Hassan and Imam Zadeh Ibrahim shrines and so on.9

Sometimes the villagers cut down Aghadar and create buildings of the same wood or make a coffin for the shrine. This shrine is not really a cover for a sacred body; the shrine itself is sanctified. It seems that the shrine and its associates (all pilgrims in the shrine) which are treated as a single being is respected. The whole space is filled with spiritual waves and as the pilgrim enters the scared area, puts his head on the tomb and starts praying. Sanctity of space is overwhelming. Based on this belief, the atmosphere for the visitor of the sacred place is spiritual, and whatever is within the place is holy and can be a link between him and the metaphysic world. In some villages, including Viyayeh village in Rudbar and Shah Nargesi village in Amarlou, they put up walls around the sacred tree.

The tree trunk (without tree branches and leafs) serves as the cosmic tree in the middle of the building and preserves the sacred place as the center of the world. Occasionally, when the sacred tree in a village (e.g Tucha village in Lashte nesha) is cut down for various reasons for examples the villagers need to build a road or the tree is withered, the women of the village leave some lighted candles on its trunk. It seems cutting the tree cannot lessen the sanctity of the tree. A perusal of literature shows that there was a shrine at the heights of Kohneh-e-Gouye village in Ranekouh Sookht e Kish.9 The name of this shrine reflecting the sanctity of a boxwood shrub burnt and perhaps it does not exist anymore. An old oak tree is planted by the shrine in the village of Shah Barzeh Kouh, at Parehsar in Talesh and, is called tooth pain tree. The tree which lies in a scared place can satisfy some of its pilgrims’ needs including healing tooth and head pains as long as some rites are observed10 (Figure 12 &13).

Aghdar in Naser Kiadah village in Lahijan, are two tangled trees, a Planer and a Fig which are well-known for their healing fruits. Though there is a charity box, people put their dedicated gifts in the gap between the two trees. They cherish the nexus between the two trees and in turn, the donation of fruit from the trees. Therefore, the space and everything in it associates with the spiritual aspects of the universe, and the pilgrim requires all beings and even objects to intercede with God and get connected to the metaphysic world. The sense of place mingles with the sacred entity, and a hierophany overwhelms the place with the spiritual waves of prayer.

This longitudinal qualitative case study attempts to provide an in-depth examination of the belief about revering trees in Gilan (Creswell, 2009). The study was carried out in seven villages across Gilan. The villages were purposively chosen by the researcher who was an instrument through which the data of the current study were collected from different sources (Observations and documents) and then analyzed.10

Data sources

Observations: The author of this paper spent four years (March 2011-July 2015) observing the daily worship activities of people in Gilan. The observations were unstructured to gather the rich data about the belief. The author ended her observations when she reached the data saturation.11 People were not aware that the researcher was observing them.12 The reason for selecting covert observation was to be sure that the participants don’t change their behaviour due to the researcher’s presence.12

Document

Documents are other sources of data that the author used to provide a thick description of the data.13 The documents used in this study are public records (see appendix), personal documents (e.g. the authors’ experiences, and beliefs) physical evidence: (artifacts).

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.14 Like any other inductive analysis, the pre-established categories are not imposed on the data. This method is recommended when the existing literature on the topic of interest is scanty. In this method of analysis interpreting the data in the light of theories and previous literature occurs when core categories emerged. To develop categories, the author started comparing meaning units constantly. Then she crosschecked the codes by getting back to the data and then finalized categories and themes after cross-analyzing the data. She independently analyzed the data and requested an expert to monitor the data analysis and interpretation.15

The beliefs of plain-dwellers could be different from the beliefs of mountain inhabitants. This is true about the herdsmen and farmers. This implies that those who believe in supernatural power may seek help from different things such as trees, stones or mountains as sacred creatures. The belief originates from the fact that human realizes that all these elements are revered as sacred creatures, not for what they are, but for their sanctity. Generally, while in mountainous places, a huge mountain could be sacred for people; plain dwellers may believe a tree has a unique sanctity because of the vegetation cover. As the foothills are situated between the mountain and the plain, the beliefs of worshipping the stones and trees are common.

Believing in the tree as an entity possessing a soul and as a reliever of the body and soul of the human at the time of loss justifies sanctifying tree of any types. Therefore, the evergreen tree represents the eternal life and the immortal soul, and deciduous tree symbolizes the world that is undergoing renewal and incessant regeneration, from the death to life, from the life to death, and it evokes a sense of resurrection and rebirth. Finally, both types of trees symbolize a plurality in unity. Sanctifying a natural phenomenon like a tree is quite common among the plain dwellers of Gilan because of the natural vegetation cover.

It is almost 2 o’clock am I see a woman in local clothes, she looks upset. She comes closer to the tree and starts opening her hand towards the trees and murmuring something. Though it is not clear what she says, it is very evident that she is beseeching the tree (Observation, 3rd March, 2014).

I see two people near the tree, one of them is a child around 6 years old and the other is a woman around 27. The child’s back is toward the tree. She is busy buckling her shoes. The woman gets angry at her and asks her to turn and respect the tree (Observation, 9th August 2011).

It seems that the use of the term "Aghadar" with the "Agha" prefix and attributing male features to trees are closely bound up with the birth or prevalence of such rituals at the time when patriarchy reached its culmination. Apparently, this is a result of the great respect for the man-totem belief. In the plain area of Gilan, the use of planer trees in the columns of residential buildings has long been common among villagers. Given the fact that these types of trees are scared in the eyes of foresters, the use of sacred wooden columns which support the roof itself and strengthen the building is fully justified.

It is summer, it is not quite hot and I am in the village of Fushah, I see a man insisting on choosing a planer tree to be used as pillars and other types are unacceptable to him. (Observation, 28th July 2015).

Generally, the coffin in the sacred shrine is made of this tree. An examination of the rites of making a pilgrimage to the tree reflect the belief in animism and sanctification of the tree as a supernatural force which can satisfy the needs of the people in the ancient Gilan; With the advent of Islam to Gilan, such sacredness has reappeared as the intercession with God. It seems that as soon as Islam was introduced to the people of this area, some beliefs have been mingled with religious rituals and have emerged in different forms. Every sacred place is a door for passing from one world to another. Therefore, the desire to create this sacred place requires creating this cosmic threshold. Cutting down the sacred tree and its death is not an end to its sanctity for the villagers who revere the trees; the dead trees are used in different buildings, and coffins.

The coffin is not only a cover for a sacred corpse but also a respect for itself. By doing this, the inhabitants believe that the trees continue to live in a different form. Even they go further and believe that a hierophany moves into a geographic zone and not only covers the tomb's area and but also the city. The human being as a myth believer thinks that burying his mortal body adjacent to the sacred entity will bring prosperity to him in the other world. Insisting on the possession of grave before his death explains why corpses have been buried near these places and the term sacred is cities. It seems that here, shrine and its associates (all visitors to the shrine) which are treated as a single entity. The atmosphere is divine, and whatever is in the space is holy and can intercede between him and the metaphysic world.

Footnotes

The author has not received any funding for this work.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Khakpour. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.