Advances in

eISSN: 2573-2862

Research Article Volume 2 Issue 5

1Department of pathology, Government medical college, India

2Department of surgical oncology, Pushpadi cancer care centre, India

3Department of pathology, Kasturba Medical College, India

Correspondence: Lakshmi Agarwal, Consultant onco-pathologist AP, Department of pathology, Government medical college, Pushpadi cancer care centre, India, Tel 9772464587

Received: October 31, 2017 | Published: December 18, 2017

Citation: Agarwal L, Agrawal M, Geetha V, et al. Histological features of tubercular lymphadenitis in hiv positive patients.Adv Cytol Pathol. 2017;2(5):150-154. DOI: 10.15406/acp.2017.02.00039

Tuberculosis is one of the most common causes of lymphadenopathy in HIV positive patients. Though the presenting complaint is same as non HIV patient, the histologic features of lymph node biopsy varies depending on the immune status. The present study is conducted to find out these differences and its relevance in diagnosis.

Material and methods: The histological features seen on lymph node biopsies, done on HIV positive patients who presented with lymphadenopathy, with or without other systemic manifestations over a period of three years were analysed. Seventy four lymph node biopsies were found adequate and provided the material for the present study. The lymph nodes biopsies were fixed in 10% formalin and were stained using Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain. Sections were stained for AFB by using Ziehl-Neelson method if H & E stained slides showed features suggestive of tuberculosis on light microscopy.

Results: In the current study, 33 cases (44%) were diagnosed as tuberculous lymphadenitis and was the second most common cause of lymphadenopathy. The CD4 counts of all these patients ranged from 10-258/�l with the CD4 count being<200 in 84.8% of cases. In the present study, granulomas were detected in 90.9% of the cases and were the most common and conspicuous feature. Confluent granulomas were more commonly seen than discrete ones. Most of the cases of caseating (75%) had more than 1 AFB/hpf whereas in the remaining cases (25%), number was less than 1/100hpf. Granulomatous lymphadenitis without caseous necrosis was seen in 2 cases (6.7%). Microabscess with granular debris without coexisting granuloma was found in 11 cases (33.3%) and all showed acid fast bacilli on Ziehl-Neelsen stain. Other features noted in present study were plasmacytosis (57.6%), paracortical expansion (12.1%) and periadenitis(30.3%). In the present study, AFB was positive in all the 33 cases. Two cases were diagnosed as tuberculosis on biopsies and confirmed as atypical mycobacterium.

Conclusion: Lymph node biopsy is a valuable tool in the evaluation of HIV positive patient to identify the causes of lymphadenopathy.

Keywords: HIV, tuberculosis, lymph node biopsy, histological features, bacilli load

Lymphadenopathy is frequent in persons with HIV infection, occurring either as one of the earliest manifestations of infection or as a finding at any time throughout the clinical course of progression through AIDS. Tuberculosis is one of the most common causes of lymphadenopathy in HIV positive patients. The presenting complaint is same as tuberculosis in non-HIV patients. However, the histologic features of lymph node in tuberculosis vary depending on the immune status of the patients. The present study is conducted to find out these differences and its relevance in diagnosing.

The histological features seen on lymph node biopsies, done on HIV positive patients who presented with lymphadenopathy, with or without other systemic manifestations over a period of three years were analyzed. Patients aged less than 14 years and inadequate samples were excluded from the study. Seventy-four lymph node biopsies were adequate and provided the material for the study. In each case, a brief and precise history was taken which included age, presenting complaints, any opportunistic infection etc. Complete blood picture and CD4+, CD8+ counts were noted wherever available. Results of Mantoux test, sputum for AFB and ESR when done were also documented. The lymph nodes biopsies were fixed in 10% formalin and were routinely processed. The histopathological evaluation of all cases was done using Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain. The number of slides studied in each case varied from 1 to 6. Sections were stained for AFB by using Ziehl-Neelson method if H & E stained slides showed features suggestive of tuberculosis on light microscopy.

In the current study, 33 cases (44%) were diagnosed as tubercular lymphadenitis and were the second most common causes of lymphadenopathy after reactive hyperplasia. The presenting complaints in this group were fever (100%) followed by cough (84%) and weight loss (75%). Generalized lymphadenopathy was seen in 25 cases (75.6%) where as cervical lymphadenopathy was found in 7 cases (21.2%). One case presented with axillary lymphadenopathy. All the patients (33) were clinically diagnosed as AIDS. A raised ESR was seen in all cases ranging from 40 to 140mm/hr. The CD4 counts of all these patients ranged from 10-258/�l with the CD4 count being<200 in 84.8% of cases (Table 1). Mantoux test and sputum for AFB were performed in 22 cases and was strongly positive in all of them. Granulomas were detected in 90.9% of the cases and were the most common and conspicuous feature. Micro abscess with granular debris without coexisting granuloma was found in 11 cases (33.3%).

CD4 counts /�l |

Number of Cases |

Percentage |

0-40 |

11 |

33.3 |

41-80 |

8 |

24.2 |

81-120 |

2 |

6 |

121-160 |

7 |

21.3 |

161-200 |

0 |

0 |

>200 |

5 |

15.2 |

Table 1 HIV positive patients with tuberculous lymphadenitis: CD4 counts (n=33)

Tuberculosis (TB) was not mentioned as a manifestation of AIDS in the earlier description of the disease from USA and Europe. The association with TB was recognized in Haitians and intravenous drug abusers.1 In developing countries, it is now recognized as one of the most common opportunistic infection in seropositive patients. It is unclear whether HIV associated TB is usually a primary, reactivated or secondary exogenous infection though reactivation of latent infection is the most important cause. Whatever the source, people infected by both HIV and TB have an accelerated progression to overt tuberculosis.2,3 Cervical lymphadenopathy was the most common site of localized lymphadenopathy in the current study and this is similar to the findings of Hadadi et al.4 In studies conducted by ‘Chaisson et al.5 & Duncanson et al.6 and coworkers5,6 it was noted that TB usually precedes the diagnosis of AIDS, presumably because TB is more virulent than other HIV associated pathogens. Their data also confirms that TB is an AIDS related opportunistic infection characterized by atypical clinical and radiological features and poor survival. Gnana et al. noted a greater prevalence of extra pulmonary and disseminated forms of TB in HIV positive individuals than in immunocompetent patients. Diagnosing extra pulmonary TB in patients with HIV is important because it is an AIDS defining illness. The most frequent forms are lymphadenitis and miliary disease.1,7,8 Lymph nodes are commonly infected by mycobacterium in patients with AIDS.9 In such patients, abscesses and purulent inflammation comprise a significant component of the histologic features of tuberculous lymphadenitis. Morphologically, in addition to the presence of polymorphs, the other criteria for the diagnosis are caseous necrosis and granulomas, of which the former is the most specific and sensitive as shown by Arora et al.10 & Nambuya et al.11 in their study on lymph nodes morphology in HIV positive patients with TB classified the tubercular node into four categories based on cellularity and number of AFB’s. These were:

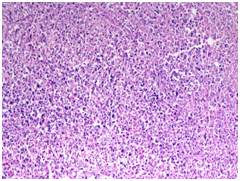

Shobhana et al.12 in their study documented 41% of their cases as tuberculous lymphadenitis with their CD4 counts varying between 113 and 422 cells/µL. The various morphological features analyzed in cases of tuberculosis included; presence and type of granulomas, neutrophilic micro abscess, periadenitis, plasmacytosis and paracortical expansion (Table 2). The morphology of the granulomas i.e. discrete or confluent and presence or absence of caseation was also noted. In the present study, granulomas (Figure 1A) (Figure 1B) were detected in 90.9% of the cases and were the most common and conspicuous feature (Table 3). Among the 30 cases with granulomas, caseous necrosis (Figure 2) was found in 28 (93.3%). Confluent granulomas were more commonly seen than discrete ones (Table 3). These findings are similar to those of other workers.8,9,10 Caseation alone was the most common specific and sensitive findings in most studies. Wannakrairot et al.13 not only found this to be the predominant feature in 74.5% of their cases but also found granulomas to be less numerous in AIDS than in non-AIDS patients.13,14 Perenboom et al.15 observed that microscopic caseation was 100% predictive of tuberculosis with a sensitivity of 69%. Most of the cases of caseating (75%) had more than 1 AFB/hpf whereas in the remaining cases (25%), number was less than 1/100hpf.15 Granulomatous lymphadenitis without caseous necrosis was seen in 2 cases (6.7%). These were subsequently diagnosed as tuberculosis based on AFB positivity. Similar non caseous granuloma may also be seen in opportunistic fungal infections, of which Candida, Cryptococcus neoformans, Histoplasma capsulatum have been reported in HIV positive patients. Hence, in cases with non caseating granulomas, AFB stain is very useful to identify tubercle bacilli and thereby ascertain the etiology of the granulomatous process. Nag et al found the highest AFB positivity was among the patients showing caseation necrosis plus ill-formed granuloma (100%), followed by caseation necrosis only (80%).9 He also documented two cases of histoplasmosis and cryptococcosis in which well-formed epithelioid granuloma without any necrosis was present.9

Features |

Number of Cases |

Percentage |

Granulomas |

30 |

90.9 |

Neutrophilic microabscess |

11 |

33.3 |

Periadenitis |

10 |

30.3 |

Plasmacytosis |

19 |

57.6 |

Paracortical expansion |

4 |

12.1 |

AFB positivity |

33 |

100 |

Table 2 HIV positive patients with tuberculous lymphadenitis -Microscopic features (n=33)

Granulomas |

Discrete |

Confluent |

Both |

Caseating(n=28) |

9(32.1%) |

14(50%) |

5(17.9%) |

Non caseating(n=2) |

0 |

2(100%) |

0 |

Table 3 HIV positive patients with tuberculous lymphadenitis: Type of granulomas (n=30)

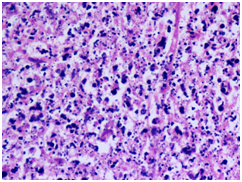

In the present study, micro abscess (Figure 3A) (Figure 3B) with granular debris without coexisting granuloma was found in 11 cases (33.3%) (Table 1) and all showed acid fast bacilli on Ziehl-Neelsen stain. In the absence of granulomas, the identification of such micro abscesses with granular debris should therefore raise the suspicion of tuberculosis in these immunocompromised patients. An AFB can be performed to confirm the same. In the current study, tuberculosis was diagnosed in these 11 patients on the basis of AFB positivity. Ukekwe et al.8 also opined that histological demonstration of AFB by Ziehl-Neelsen stain in TB is the goal standard for a diagnosis of TB.8 Four cases (36%) showed langhans giant cells. Priyanka Chand et al.14 found caseous necrotic material with degenerated inflammatory cells without epithelioid cell granulomas in 34.4%.14 Wannakrairot et al.13 in their study noted that extensive nuclear debris was present in 10% of their cases, sometimes with scattered neutrophils and occasional eosinophils.13 Langerhans cells were rarely present. The necrosis was accompanied by a minimal granulomatous response that was not distinctive and was discernible only focally. The reaction was represented by scattered epithelioid histiocytes associated with marked intervening edema. Shenoy16 & Jayaram17 & Kraus18 along with their co workers have noted neutrophilic micro abscesses in approximately 30% of their cases and are in concordance with findings of the present study.16–18 In these cases, with neutrophilic micro abscesses (n=11); it was noted that the bacillary load was higher in patients with lower CD4+ count (Table 4). These findings are similar to those of Nambuya et al.11 They noted that numerous bacilli were found in granular debris in their study group. It was seen in 6 of the 11 cases (54.5%) of patients with CD4 count<40. Similarly, patients with low CD4 count (<200) were found to have high bacilli load i.e. 72.2%. The relationship of CD4+ count with presence of micro abscess and AFB in present study is in concordance with that of Nambuya et al.11 This unusual histopathology of tuberculosis in AIDS (i.e. abscesses and organisms) has been attributed to a compromised immune status and an inability to mount an adequate cellular response. Other features noted in present study were plasmacytosis (57.6%), paracortical expansion (12.1%) and periadenitis(30.3%). Ngilimana et al.19 in their study documented the presence of numerous blood vessels and abundant plasmacytosis in the non-necrotic areas.19 The gold standard for a definitive diagnosis of tuberculosis rests on the demonstration of AFB on histopathology or by culture studies. In the present study, AFB was positive in all the 33 cases. Bacilli load was categorized into four groups depending on the number of AFB’s present per high power field (HPF) i.e. AFB<1/100 HPF, AFB1-10/HPF, AFB>1/10-100hpf, AFB>10/HPF and the results are depicted in tabular form (Table 5). All these patients were clinically categorized as AIDS. None were in the ARC or AIDS at risk categories.

CD4+ in �l |

MICROABSCESS |

AFB<1/100HPF |

AFB 1-10/HPF |

AFB>10/HPF |

<40 |

6 |

NIL |

3 |

3 |

120-160 |

2 |

NIL |

1 |

1 |

>200 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

NIL |

Table 4 HIV positive patients with tuberculous lymphadenitis: correlation between microabscess formation, CD4+ count and AFB (n=11)

Bacilli load |

AFB<1/100hpf |

AFB1-10/hpf |

AFB>1/10-100hpf |

AFB>10/hpf |

Number of cases |

10(30.3%) |

13(39.3%) |

2(6%) |

8(24.4%) |

Table 5 HIV positive patients with tuberculous lymphadenitis: Evaluation of bacillary load (n=33)

Figure 3

3A) Neutrophilic microabscess with granular debris(H&E 10X)

3B) Neutrophilic microabscess with granular debris(H&E 40X)

Nambuya et al.11 in their study observed that the number of AFB‘s tended to correlate with AIDS status. These patients were more likely to have abundant AFB than those with AIDS related complex and AIDS risk patients. Further, no AIDS patients with a positive mycobacterial culture had a negative AFB stain. Mycobacterium avium and mycobacterium intracellulare are two closely related, non-chromogenic mycobacteria that are grouped together to form the Mycobacterium avium intracellular complex (MAC). These are the second most common mycobacteria isolated from patients with AIDS. Unlike TB, MAC disease occurs later in the course of AIDS. The histopathology of MAC infected tissues reveals non-necrotizing granulomas which are often poorly formed and associated with clusters of foamy macrophages. Klatt et al.20 studied pathologic findings of disseminated MAI infection in 12 patients with AIDS. In every patient, the distinctive microscopic features on H&E staining were poorly defined granulomas consisting of pale blue striated histiocytes filled with mycobacteria. Well-formed granulomas with fibrosis, necrosis and epithelioid histiocytes were present in less than one third of the cases. It occurs as a late complication of HIV infection, often with CD4+ count less than 50/µl. In the present study, two cases were diagnosed as tuberculosis on biopsies and confirmed as atypical mycobacterium by culture. However neutrophilic micro abscesses were also found in 9 cases of lymphadenitis due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Thus, these findings of neutrophilic micro abscess are not specific for atypical Mycobacteria. However, presence of such micro abscesses should raise the suspicion of atypical mycobacterial infection and culture should be requested for definite diagnosis. Kraus et al had opined that culture should be done in presence of micro abscess and ill-defined granulomas to rule out atypical mycobacteria.18

The various clinical and microscopic features in case of high and low bacillary load were compared and are depicted in a tabular form in Table 6. No statistically significant difference was noted in the two groups with respect to clinical presentation and morphological features. A higher rate of acid fast bacilli positivity (62.5%) was found in cases with neutrophilic micro abscess, most of which did not show discreet granulomas. Langhans giant cell was found in only 1 case (12.5%). Therefore, in the absence of Ziehl-Neelsen staining, these cases would have been dismissed as acute necrotizing lymphadenitis. Though marked difference in percentage was observed between the two groups in relation to neutrophilic micro abscess (62.5% and 20% respectively), it was not statistically significant. This discrepancy may be attributed to the small sample size available for analysis.

Features |

High Bacillary Load AFB>10/Hpf (N=8) |

Low Bacillary Load AFB<1/100hpf (N=10) |

Common Clinical Features |

Fever and Cough |

Fever and Cough |

Lymphadenopathy: |

||

Generalized |

50% |

80% |

Localized |

50% |

20% |

ESR in mm/hour (mean) |

110 |

80 |

Mantoux Test (N=4 In Each Group) |

Positive in one Case |

Positive in one Case |

CD4+ count: |

||

<50/�l |

50% cases |

20% cases |

>50-<200/�l |

50% cases |

80% cases |

Caseation |

87.50% |

90% |

Neutrophilic microabscess |

62.50% |

20% |

Granulomas: |

||

Confluent |

5 cases |

6 cases |

Discreet |

3 cases |

Nil |

Absent |

Nil |

one case |

Both(discrete and confluent) |

Nil |

3 cases |

Langhans giant cells |

1 case (12.5%) |

4 cases (40%) |

Table 6 Tuberculous lymph nodes: Clinical and morphological features in high and low bacillary load groups

Caseous necrosis was a distinctive feature even in the absence of granulomas or in the presence of poorly formed ones in case of tuberculosis. Neutrophilic micro abscess with granular debris without co existing granulomas had higher bacillary load. This stresses the need for routine AFB staining in all such cases. Hence lymph node biopsy along with AFB staining is a valuable tool in the evaluation of HIV positive patient to identify the cause of lymphadenopathy and to confirm the diagnosis of tuberculosis.21

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Agarwal, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.