eISSN: 2378-3176

Case Report Volume 5 Issue 3

Department of Urology, Pinderfields hospital, UK

Correspondence: Michalis Varnavas, Department of Urology, Pinderfields hospital, UK

Received: June 14, 2017 | Published: September 6, 2017

Citation: Varnavas M, Khan A, Reall G, Dooldeniya M (2017) Malignant Mesothelioma of the Spermatic Cord. Urol Nephrol Open Access J 5(3): 00169. DOI: 10.15406/unoaj.2017.05.00169

Paratesticular malignant mesothelioma is a very rare entity which mirrors the aggressive nature of mesotheliomas arising from other serous membranes in the body. Reports on their incidence vary and stand to 0.3-1.4 % of all malignant mesotheliomas. Malignant mesothelioma arising from the spermatic cord is extremely rare with only 14 cases being reported in the past. We report a case of a malignant mesothelioma of the spermatic cord in a 52-year-old man who presented to our department with a two year history of a right scrotal mass. He was treated initially with a right sided orchidectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy. Despite this he developed local recurrence of the disease and eventually distant metastasis. Regardless of its rarity paratesticular mesothelioma needs to be suspected, especially in patients with a history of asbestos exposure. Early and accurate diagnosis with early surgical excision remains the most important factor for effective treatment and control of this disease. In addition, after the diagnosis is confirmed as malignant mesothelioma, a more aggressive management including a second-look operation with pelvic lymphadenectomy or adjunctive chemotherapy has been suggested to produce better outcomes.

Malignant mesothelioma is a rare primary aggressive neoplasm arising from the mesothelial cells, these cells from the lining of the various serous membranes of the body. The most common sites are the pleura (70-75%), the peritoneum (10-20%) and pericardium (5%). The development of the tumour has been linked to asbestos exposure especially in pleural disease. In the UK asbestos exposure accounts for 94% of the mesothelioma cases. A recent case demonstrated malignant mesothelioma of the spermatic cord in an 80 year old man who worked as a railway worker with a long history of asbestos exposure.1 The latency period between asbestos exposure and tumour detection varies between 20 and 40years. There were 2700 new cases of mesothelioma in the UK in 2014 according to cancer research UK accounting for about 1% of all new cancer cases diagnosed in the year. Malignant mesothelioma of the tunica vaginalis of the testis (paratesticular) is very rare accounting 0.3-1.4% of all mesothelioma cases.2 And when it arises from the spermatic cord is extraordinarily rare indeed. Our literature review has revealed 14 cases being reported in the English literature as of February 2017.

We present the case of a 52-year-oldman that presented initially in our urology clinic with a 2-year history of a lump on his right testicle. His past medical history included a perforated duodenal ulcer at age seventeen, hypertension and a current smoker of twenty per day but no previous history of asbestos exposure. He denied any change in size, shape or consistency of the lump during this time. On examination his abdomen was soft not tender. The left testis felt normal while there was a right sided hydrocele. Separate from the right testicle there was a hard, irregular mass which was mobile and not tender. An urgent US scan was organised from clinic (Figure 1), this confirmed a 20mmx 15mm x 17mm vascular mass, adjacent to and possibly arising from the superior right spermatic cord.

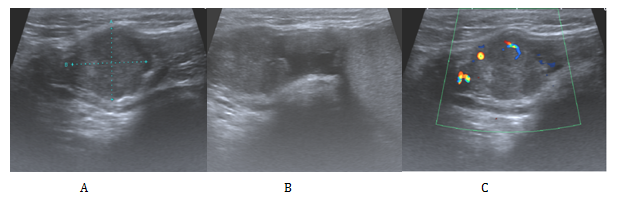

Figure 1 Ultrasonographic appearances of the tumour.

A: A is a 2cm x 1.7cm x 1.5cm heterogeneous lesion arising from or adjacent to the right spermatic cord.

B: Here it is shown clearly to be separate from the right testis and epididymis.

C: Doppler study confirmed a solid component with some internal vascularity.

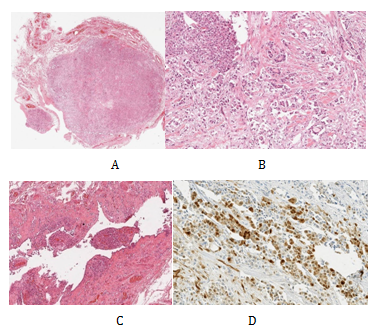

The findings of the clinical examination and ultrasound scan were discussed in our multidisciplinary team meeting (MDT). The consensus for the meeting was that the available evidence was inconclusive on the nature of the tumour and offered to patient radical orchidectomy which was performed the following week. Operative findings were of a lesion (query chronic inflammation) adherent to the cord and unable to separate but a standard radical orchidectomy carried out. The histological analysis revealed a tumour primarily located in the spermatic cord (Figure 2A). This was fairly circumscribed and composed of nests and sheets of cells with abundant clear cytoplasm, large pleomorphic nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Figure 2B). There was frequent mitotic activity and focal necrosis. The tumour had an infiltrative margin with cords of cells infiltrating between densestromaeliciting a desmoplastic reaction. Focally at the edge of the tumour, there is a small papillary component. In conclusion appearances were highly suggestive a poorly differentiated tumour which was confirmation of being a malignant mesothelioma after immunohistochemical analysis.

Figure 2 Low power H&E of tumour x10 - demonstrates a well circumscribed but infiltrative solid tumour located primarily in the spermatic cord (A). High power H&E of tumour x40 (B). Low power H&E of background mesothelial proliferation x10 - small papillary mesothelial excrescences on the capsular surface of the testis containing psammoma bodies and focal vascular invasion (C). Immunohistochemistry calretinin positive - strongly positive within tumour cells for calretinin, confirming mesothelial origin of tumour cells (D).

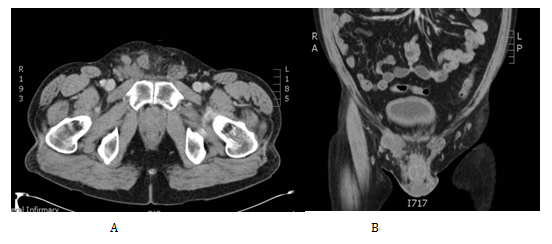

As a result of the histological findings a subsequent CT Chest/Abdomen/Pelvis was organised, this showed no evidence of residual or metastatic disease. The case was then discussed in the oncology MDT. The decision at that point given the diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma which offers a high risk of recurrence was to offer adjuvant chemotherapy with Cisplatin Pemetrexed. He was subsequently closely followed up by the clinical oncologist at 3-6 monthly intervals. Unfortunately 13months after his chemotherapy he presented in clinic with a right inguinal mass. On examination this was overlying his right pubic bone extending down the line of the inguinal canal and into the superior aspect of his right hemiscrotum. His US and CT (Figure 3) confirmed a 9x4.5x4 cm multilocular malignant mass consistent with local recurrence. He subsequently received a high dose palliative radiotherapy to the recurrence (40Gy 15 fractions).

Figure 3 Cross section tomographic appearance of the recurrence in the right groin in the transverse (A) and coronal (B) planes.

Following the completion of his radiotherapy he presented early in clinic after 2months with two malignant deposits at the base of his penis at the left side. At that stage he was offered palliative chemotherapy with cisplatin and pemetrexed. He had 6 cycles in total. Immediate cross sectional imaging showed disease regression. However, this was a short lived response as he subsequently developed an enlarging mass on the base of his penis; this was treated with another 5 fractions of radiotherapy. Subsequent CT scans (Figure 4) confirmed progression of disease with new pulmonary metastasis, pelvic and hilar lymphadenopathy and metastasis in the right psoas and T3. He had another 2 cycles of carboplatin and pemetrexed chemotherapy which was discontinued as there was no clinical improvement. He was at that point referred to the palliative team for symptomatic treatment. At the later stages of his disease, he developed an enlarging fungating tumour in the base of the penis which was his primary source of discomfort. This was discussed in our tertiary centre and was felt that penectomy and wound debridement would create significant wound management problems and thus was not attempted. He passed away on the 37months after his initial presentation.

Our research has shown that paratesticular mesotheliomas occur at a wide range of ages (7-87years) but most commonly present at the ages of 60-80. The vast majority arise from the tunica vaginalis and very rarely from the epididymis or the spermatic cord. With regards to the pathogenesis an occupational or family exposure to asbestos is seen in 40% of cases.3 This a much lower percentage than the one found in other sites of mesothelioma. Other causes implicated include trauma, long term hydrocele and previous herniorrhaphy.4,5 Clinically, the most common presentation is a scrotal mass 30% or an expanding hydrocele 55%.3,4 The differential diagnosis after the initial examination varies, and includes other testicular tumours, hydrocoele, epididymitis, inguinal hernia, and spermatocele or adenomatoid tumour.

The combination of an accurate history, examination, radiology, and the acquisition of pathology is essential in the early diagnosis of mesothelioma. After the initial assessment, investigations commonly include an ultrasonographic characterisation of the tumour followed by accurate staging with a chest radiograph and a subsequent CT chest/abdo/pelvis. MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and PET (positron emission tomography) have also been used to evaluate the disease. Definitive diagnosis is by histopathological analysis. Three subtypes of paratesticular malignant mesothelioma according to their microscopic appearance have been reported. These are pure epithelial, mixed type and very few pure sarcomatous cases.5 Architectural pattern are usually papillary or tubulo-papillary. Immunohistochemically, mesotheliomas are positive for cytokeratin CKAE1/AE3, CK7, CK5/6, EMA, thrombomodulin, K2-40, calretinin and WT1 and negative one for CK20, BerEP4, B72’3, MOC-31 and Leu M1.6

Paratesticular malignant mesotheliomas are aggressive neoplasms capable of widespread local involvement as well as lymphatic and hematogeneous metastases. In view of this they are usually diagnosed at advanced stages and have poor prognosis. Para-aortic lymph nodes are the most frequently and primarily involved, whereas pelvic (iliac and obturator) nodes are usually involved in more advanced stages. Local recurrence after primary radical orchiectomy and extensive surgical resection occurs in 60% of patients within 2years, with median survival of 24months.3,7 The most important prognostic factor for survival is the age of patient at the time of diagnosis, with significantly better survival in patients younger than 60years of age. Other predictors of mortality include the tumour’s histological pattern and differentiation. Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma seems to have a better prognosis.8

Consensus is that initial management of localised disease should be with radical orchiectomy and extensive surgical excision of suspicious sites. Some authors have also suggested a second-look operation with pelvic lymphadenectomy or adjunctive chemotherapy this can be in the presence of metastatic disease but no timescale has been defined regarding how soon after primary surgical removal of the tumour.2 A more limited conservative approach should be discouraged because it is almost always complicated by local recurrences. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy do not increase survival rate significantly, unless distant metastases are present at diagnosis.

None.

All authors declared there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2017 Varnavas, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.