eISSN: 2378-3176

Review Article Volume 9 Issue 1

1Jaber El Ahmed Military Hospital, Nephrology department, Kuwait

2Faculty of Health and Science, University of Liverpool, Institute of Learning and Teaching, School of Medicine, Liverpool - United Kingdom

3College of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Egypt

Correspondence: Fedaei Abbas, Consultant Nephrologist, Jaber El Ahmed Military Hospital,Nephrology department, P.O. Box 454, Safat 13005, Kuwait, Tel +965 97529091

Received: December 29, 2020 | Published: February 26, 2021

Citation: Abbas F, Abbas SF. De Novo and recurrent thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) after renal transplantation: current concepts in management. Urol Nephrol Open Access J. 2021;9(1):2-30. DOI: 10.15406/unoaj.2021.09.00303

Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is a well-recognized complication of kidney transplantation that leads frequently to allograft failure. This serious outcome depends greatly on the underlying etiology as well as the timing of therapeutic interventions. TMA syndromes may occur with no previous history of TMA, i.e., de novo TMA, mostly due to medications or infection, or more frequently recurs after kidney transplantation i.e., recurrent TMA in patients with ESRF due to the atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS). On the other hand, patients with shiga-toxin induced HUS (classic HUS), particularly in childhood has a favorable prognosis. One of the fundamental tools of management of this disease is the genetic screening for abnormal mutations, determination of which will recognize the tools of therapy and consequently outcome of the disease to a large extent. While patients with CFH and CFI mutations have a worse prognosis, other patients with MCP mutations-for example- have a more favorable prognosis. Accordingly, plan of therapy can be thoroughly drawn with a better chance of cure. Unfortunately, the successful use of the biological agent “eculizumab”, an anti-C5 agent, in some of these syndromes is largely impeded by its high cost linked to its use as a life-long therapy. However, a new therapeutic option has been recently admitted ameliorating this drawback and improve the cost-effectiveness balance.

Keywords: thrombotic microangiopathy- de novo tma - recurrent tma - renal allograft

TMA, thrombotic microangiopathy; MAHA, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia; HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; aHUS, atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura; KTR, kidney transplant recipients; CFH, complement factor h; CFI, complement factor I; MCP, membrane cofactor protein; THBD, gene encoding thrombomodulin; PE, Plasmapheresis; mTORi, Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors

The evolution of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) after renal transplantation, either de novo or recurrent disease, is a well-documented complication that not only affects allograft function, but also adversely influences patient and allograft survival.1 Management of this devastating disease depends largely on the underlying etiology. While the shiga toxin-associated HUS (classic HUS) is usually self-limited with a favorable prognosis, the complement-mediated HUS, (atypical HUS, aHUS) usually carries worse outcome that requires a more sophisticated therapeutic approach.1 In 1981, Shulman et al.4 described an association between cyclosporine (CyA) and TMA for the first time.2 TMA was also linked to the most used CNI, tacrolimus with an estimated incidence of approximately 3-14 % in some series3 and increases up to 25% in others.4 aHUS is a systemic disease involving the kidney and recurs in up to 100% of renal transplant, with poor allograft outcome.8 Pathogenesis is due to dysregulation of the alternative complement pathway that triggers uncontrolled cleavage of terminal complement protein C5 with excessive C5b-9 complex production.5 This cascade results in endothelial injury, increased expression of adhesion molecules that consequently followed by fibrin-rich micro-thrombi with an end-organ ischemia, thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA).5–7 In this review we will shed some light on the recent concepts in management of different forms of TMA.

Definition: Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) refers to a histopathologic entity that includes vessel wall thickening (arterioles and capillaries), intraluminal thrombi and vessel luminal occlusion. The resultant platelet and RBCs consumption at the level of microvasculature of vital organs including the kidney, leads to thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA). Two clinical situations with overlapping features were recognized; thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) with neurological features are essential features of the TTP but not in the HUS.9

Etiology: KTR can develop HUS either de novo or as a recurrent disease:

Prevalence

De novo HUS: the reported rate of de novo HUS is about 3-14 % of KTR.3,19,20 The following list includes factors that are particularly encountered in KTR:21–23

- Switching the patients on CyA immunosuppression to tacrolimus can reverse the CyA-induced HUS in more than 80% of patients.11 Data is limited as regard the evidence clarifying this response.

Recurrent HUS: While more than 90% of the childhood-onset HUS is mostly related to the Shiga toxin-producing E. coli with a recurrence rate of less than 1% of patients after renal transplantation,24 many patients with complement-mediated HUS (aHUS) have recurrence after transplantation. The reported rate of recurrence in patients on dialysis secondary to HUS ranges between 25 and 50%.25–28 However, recurrence is uncommon in infection-related HUS. On the other hand, the estimated rate of recurrence for complement-mediated HUS is very frequent and depends to a great extent on the type of genetic mutations.24 While the estimated rate of recurrence has been reported to be 50-100% in mutations involved CFH and CFI, the reported rate is only 15-20% in mutation involving membrane cofactor protein (MCP).24 A given explanation for this low recurrence incidence of MCP-associated HUS is that MCP is highly expressed in the kidney, so that it is rapidly restored after transplantation of a new graft.29

Other reported risk factors of HUS recurrence include:

Clinical presentation: Both de novo and recurrent HUS have a similar presentation (microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA), thrombocytopenia and AKI). Low platelet count, increased serum creatinine with evidence of hemolysis (reticulocytosis and schistocytes on peripheral smear and increased LDH) are usually encountered. A hematuria/proteinuria syndrome can be also seen. Nevertheless, this presentation is not universal, as some patients may present with only graft dysfunction with abnormal urine analysis.3,30 As regard timing of presentation, de novo HUS typically presents within the first three months post-transplant,24 while the recurrent HUS usually presents within days to weeks.31,32

Diagnosis: Any KTR presented with allograft dysfunction, should raise the possibility of HUS diagnosis, particularly so, if there is associated hemolytic anemia with drop of the platelet count. However, final diagnosis is ultimately documented by tissue diagnosis.

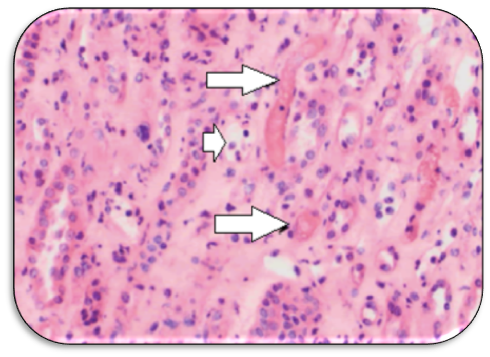

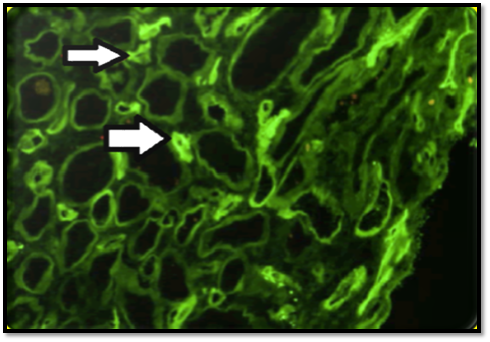

Pathology: the typical histopathological finding includes glomerular and arteriolar thrombosis, intra-capillary engorgement with RBCs and RBCs fragments, basement membrane detachment, endothelial swelling with glomerular ischemia. With healing of the arteriolar walls, an onion-skin hypertrophy supervenes Figure (1,2).6

Figure 1 Medullary region of allograft biopsy obtained at onset of HUS symptoms with small vascular thrombi (arrows) and scattered dilated capillaries with peritubular capillaritis (short arrow) (Adapted from: Wrenn SM et al.36 open access).

Figure 2 C4d IF staining of less than 50% of the peritubular capillaries (arrows), noted on the initial allograft biopsy. (Adapted from: Wrenn SM et al.36 open access).

Two pathological entities in tissue biopsy can be encountered in allograft biopsy:

Differential diagnosis: of AMR from HUS is difficult, as both conditions share in allograft dysfunction and resistance to anti-rejection therapy. However, the presence of predominant endarteritis with global involvement of the whole vascular tree of the graft is characteristic of the acute AMR.6

Location: In about 30% of cases, TMA is strictly confined to allograft tissues with no associated manifestations of hemolysis or platelet count drop. In this situation, tissue diagnosis will be the only resort. Any young KTR presented with severe hypertension associated with decline in allograft function, should raise the possibility of TMA.3

Pathogenesis: An endothelial cell injury associated with imbalance between thrombotic and antithrombotic factors at the level of microvasculature has been postulated to be the culprit mechanism. Risk of TMA appears to be highest at the first three months post-transplant, with females and elderly patients appear to be more vulnerable.4

Classic HUS: internalization of the Shiga toxin occurs in the endothelial cells, which is followed by activation and through cytokine release and endothelial damage, could develop a cascade of endothelial disruption, platelet clustering and thrombosis. The latter is the hallmark of TMA.33

CNI related: through potent vasoconstriction, endothelial toxicity, prothrombotic and antifibrinolytic criteria,28,34 CNI can precipitate HUS. CyA and tacrolimus have the ability to up-regulate the production of vasoconstrictors elements e.g., endothelin-1 and angiotensin II that results in evolution of a pro-coagulation state that trigger platelet aggregation and thrombosis.28

Two different types of TMA have been described by Schwimmer and his associates (2003) in their retrospective study: systemic (62%) and a localized type (38%) without systemic extension.3 Graft loss have been more observed with the systemic form (more aggressive and disseminated disease), as compared with the localized type.3

AMR and HUS: it was Satoskar et al.34 who first admitted AMR as a cause of TMA. They found 55% of their biopsies were C4d positive. Another study found 88% of biopsies had C4d deposits.35 Finally, both C4d staining of peritubular capillaries and DSA express the two-fundamental links between TMA and AMR.6,36

Genetic predisposition: The absence of clear evidence of any HUS manifestation before transplant denotes de novo HUS diagnosis, however, Broeders et al.37 describes a case of silent polymorphism of factor “H” that present as de novo HUS after transplant.37 So, genetic predisposition to aHUS may be hidden in a “silent status” until clinically unmasked through an inciting factor (second hit) like transplant surgery or an associated infection.38

Risk factors of de novo TMA: the following factors have been considered:

Potent vasoconstriction

The mTORi: Rapamycin has reported to be associated with de novo TMA.40

Role of complement abnormality in aHUS recurrence: the outcome of aHUS is largely dependent on the type of complement aberrations.34,42–44

III. Combined mutations

It is difficult to interpret due to rarity of cases. However, heterozygous mutations in CFI/MCP and CFH/CFI were devoid of recurrence after renal transplantation, while other combinations of CFH/ CFI mutations and another with three mutations in MCP/CFH/CFI have been reported to recur after transplantation.44,45

Prognosis

Prognosis of de novo is usually better than that of recurrent HUS.4 HUS has also a favorable prognosis if the lesions were confined to the glomeruli (localized form).46 The one- and five-year’s survival rates of KTR with ESRF due to HUS were reported to be lower with HUS recurrence as compared with those without recurrence in one study (33% versus 57% at one year and 19% versus 57% at five years).32

De novo versus recurrent TMA: the fundamental differences between de novo and recurrent TMA are summarized in (Table 1).

|

No |

Item |

De novo HUS |

Recurrent HUS (aHUS). |

|

(1) |

Etiology |

Medications, e.g., CNI,10,11 viral infection, ischemia /reperfusion injury & AMR. |

Dysregulation of complement activation due to genetic defects in the alternative pathway (complement-mediated) or atypical HUS.18 |

|

(2) |

Timing |

Typically, within the first 3 months post-transplant.24 |

|

|

(3) |

Prevalence |

Recurrence rate: - In patients on dialysis due to HUS: 25-50%.25–28 - 50-100% in mutations involved CFH & CFI. - Only 15-20% in mutations involving MCP.24 |

|

|

(4) |

Pathology: |

Glomeruloarteriolar thromb-osis, capillary engorgement, endothelial swelling. |

- Same. |

|

(5) |

Clinical presentation |

MAHA, thrombocytopenia and AKI. |

Similar presentation.

|

|

(6) |

Prognosis |

-Better than recurrent HUS [4]. - Favorable prognosis with the “localized” form.46 |

I. Worse outcome: 1]CFH mutations: recurrence rate: 76%, graft loss 86%.31 |

|

2] CFI mutations: recurrence 92%, Graft loss: 85%. |

|||

|

3] C3 & CFB mutations: high rate of recurrence.6 |

|||

|

II. Better outcome: 1] Anti-CFH autoantibodies: better outcome. 2] MCP mutations: recurrence of aHUS is rare.6 3] THBD mutations: low risk of recurrence.39 |

|||

|

(7) |

Prevention |

Avoid “risk factors” (see below). |

Eculizumab (see below for more details). |

|

(8) |

Treatment |

Hold the culprit drug. PE. Eculizumab (if associated with genetic abnormality). |

Eculizumab (see the detailed protocol). Bortezomib. Rituximab. Eculizumab “upon recurrence”.7 |

Table 1 Main differences between de novo and recurrent HUS

Prevention of HUS recurrence: to prevent HUS recurrence the following therapeutic approaches should be adopted:

Donor selection: avoid living related donor kidney for a patient developed ESRD due to complement-mediated HUS, the following explanations have been suggested:

Therapy of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA)

General concepts

TMA is a clinical phenotype that encompasses thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), shiga toxin-associated HUS (classic HUS) and atypical HUS (aHUS). While TTP responds well to plasma exchange (PE) and shiga toxin-associated HUS can be managed by supportive measures, the atypical HUS (aHUS), on the other hand, is a life-threatening event that necessitates more aggressive therapeutic maneuvers.8 Atypical HUS (aHUS) is a devastating disease presents usually with thrombocytopenia, hemolysis and renal failure. Prognosis is ultimately poor due to unlimited complement activity leading to thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). While 50% of untreated patients progress to ESRF, 10% of them can be lost in its acute phase.50 KTx is a robust therapeutic option. Unfortunately, the high rate of recurrence with graft loss is a real threat.51 Trial of PE therapy has a very limited response with ultimate return to dialysis.52 The newly administrated biological agent, eculizumab (a complement 5 blocker) of increasing popularity due to rapid resumption of allograft function.53 Moreover, KTx can be successfully performed under an umbrella of eculizumab prophylaxis.54 Considering the high cost of this biological agent is of great concern, especially so, with applying the “lifelong prophylactic strategy”,55,56 consequently, alternative options have been recently addressed (see below).

Treatment of de novo HUS

CNI/mTORi withdrawal or dose reduction to a lower trough level, whatever the suspected etiology. Considering these agents as common causes of HUS, their withdrawal/reduction can induce resolution of de novo HUS.21,28 Switching to tacrolimus is another option for patients receiving CyA.

Alternative options: Eculizumab with belatacept combination: the use of eculizumab combined with belatacept has been successfully applied as an alternative to CNI and to reverse a case of de novo aHUS in a patient with a heterozygous deletion in CFHR3-CFHR1 gene. Dedhia et al.8 presented a case of de novo aHUS after kidney transplantation in a patient with a heterozygous complement factor H-related protein (CFHR)3-CFHR1 deletion with a successful response to eculizumab therapy, with utilizing belatacept, a CD80-binding fusion protein, for maintenance immunosuppression as an alternative to the CNI agent, tacrolimus.8

Treatment of recurrent aHUS

The significant role of a complement-mediated process as a culprit mechanism of HUS recurrence is now universally accepted. However, all other precipitating factors should be excluded before considering eculizumab therapy:

Depending on the current available data,53,61–64 eculizumab therapy has its clear beneficial impact on the recurrence of aHUS disease. Many patients can be withdrawn from dialysis, with elevation of the platelet count and normalization of the LDH level. Therefore, all patients with recurrent HUS should receive eculizumab therapy as followed:

Alternative options: in view of the high cost of eculizumab therapy, a recent discussion of experts in the last “EDTA 2017” conference, described a new strategy for better “cost-effectiveness” rates. The alternative options include the following:

Bortezomib: Depletion of plasma cells with the proteasome inhibitor “bortezomib” has been proposed as a new therapeutic option for management of the recurrent aHUS.6

Eculizumab “upon recurrence”: Recently, Brand (2017) and his colleagues presented a successful renal transplantation of aHUS patients without the need for eculizumab prophylaxis.7 Along 2.6 years follow-up these transplants and with avoiding risk factors that can trigger aHUS recurrence (e.g., surgery and viral infection), they succeeded to get a decline in recurrence rate up to 10%. Moreover, they successfully achieved a reasonable cost-effectiveness rate with “eculizumab upon recurrence” strategy that depend primarily on monitoring the risk of recurrence through observation of the trigger factors. They also suggest monitoring the early markers e.g. thrombomodulin and soluble C5b-9 in urine.66

Both “eculizumab induction” and “lifelong maintenance therapy” strategies could result in an “over treatment” burden, which will not only has a negative impact on the “cost-effectiveness” balance but also will exaggerate the untoward effects burden.No evidence is currently available documented that curative eculizumab is less effective than prophylactic strategy. Therefore, the policy of “therapy upon recurrence” is preferable for a better cost-effectiveness balance. Furthermore, the need of early markers of disease recurrence appears to be urgently warranted. Promising markers of recurrence include thrombomodulin and soluble C5b-9 in urine.7 These markers are not only used for predicting HUS recurrence, but also can help in evaluating eculizumab response as well as drawing the best therapeutic plan. Fulfillment of these parameters in large cohorts of randomized studies can help achieve the best cost-effective strategy.66

Brand (2017) and his associates66 used the decision analytical approach (Markov modelling) to evaluate five strategies: (1) Dialysis therapy only; (2) Kidney transplantation (KTx) without eculizumab;(3) Eculizumab upon recurrence: KTx plus 3 mo. of eculizumab therapy in case of HUS recurrence; (4) Eculizumab induction: KTx plus 12 months of Eculizumab prophylaxis, and re-treatment with HUS recurrence, and (5) Eculizumab lifelong: KTx plus lifelong Eculizumab prophylaxis. They demonstrate that eculizumab therapy results in substantial benefit in QALYs (quality-adjusted life years). Moreover, applying the new suggested strategy of “eculizumab upon recurrence” is more efficacious in the concept of QALYs gain, as compared to both “eculizumab induction” and “lifelong eculizumab” prophylaxis. The latter two, however, can result in a higher cost-effective balance. Finally, living donor kidney transplantation for aHUS patients appears more feasible with no need for eculizumab prophylaxis as long as monitoring of trigger factors of recurrence was of utmost priority.66

The increasing awareness of TMA pathogenesis and its risk factors – despite rare – is of growing interest among the transplant community. The proper preparation of the KTR, particularly as regard genetic mutations abnormalities related to the evolution of aHUS (complement-mediated HUS) is a fundamental step before commencing the transplant. This is particularly crucial in ESRF patients due to HUS disease. On the other hand, the perfect evaluation of KTR can result in detection of a simple avoidable etiology for HUS e.g., medications, switching of which can result in a complete disease reversal and avoidance of unnecessary costly medications. The latter, however, is under robust investigations to reduce their cost and improve the cost-effectiveness balance e.g., “therapy upon recurrence” strategy. However, more efforts still warranted to simplify these complicated therapeutic strategies of this devastating disease and guarantee better patient and graft outcome.

None.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2021 Abbas, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.