eISSN: 2577-8285

Research Article Volume 4 Issue 1

1Department of Kinesiology and Health, Wright State University, USA

2Maple Tree Cancer Alliance, USA

Correspondence: Wright State University, Department of Kinesiology and Health, 3640 Col Glenn Hwy, Dayton, OH 45435, USA

Received: July 28, 2018 | Published: January 20, 2020

Citation: Wonders KY, Oostveen A, Wise R, et al. The role of prescribed, individualized exercise in attenuating sleep disturbance and deprivation during cancer treatment. Sleep Med Dis Int J 2020;4(1):1-4. DOI: 10.15406/smdij.2020.04.00064

Approximately one quarter of cancer patients are diagnosed with chronic insomnia, presenting as restlessness, trouble falling asleep and increased sleep-wake hours throughout the night. Sleep disturbances and deprivation negatively impacts the patient’s quality of life, in terms of impaired mood, daytime fatigue, compromised immune function, and increased risk of depression. Pharmacological therapies often result in negative side effects. However, exercise is safe in a cancer population and has long demonstrated positive benefits in relation to improved treatment outcome.

Purpose: As such, the purpose of this investigation was to examine the role of prescribed, individualized exercise in mitigating sleep disturbance associate with cancer treatment.

Methods: This controlled trial evaluated the effects of individualized exercise therapy in 253 patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment. Study participants underwent standard prescribed chemotherapy schedules, and were excluded from the study if they had pre-existing cardiac, liver, and bone marrow conditions prior to treatment. Each participant completed the Sleep Condition Indicator questionnaire at the start and conclusion of their treatment regimen. During their treatment, patients participated in a 12-week individualized, supervised exercise program through Maple Tree Cancer Alliance. An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was done to compare groups at each follow-up assessment using the baseline pre-chemotherapy measure as a covariate. A significance level of p< 0.05 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results: Twelve weeks of prescribed, individualized exercise had a positive impact on fitness parameters, as well as sleep. Muscular strength, muscular endurance, and cardiovascular endurance significantly improved from baseline (average increases of 3.1 kg, 3.4, and 2.9 ml/kg/min, respectively. P<0.05). In addition, time to fall asleep, sleep quality, and early wake time were all significantly improved (average percent increases of 75.15%, 61.61%, and 160.61%, respectively. P<0.05).

Conclusion: Twelve weeks of individualized exercise improved fitness parameters and mitigated symptoms of sleep deprivation and disturbance during chemotherapy treatment.

Keywords: muscular strength, muscular endurance, and cardiovascular endurance

NCCN, National comprehensive cancer network; REM, rapid eye movement

Insufficient sleep has been a growing concern for cancer patients, especially those receiving chemotherapy. Approximately one quarter of cancer patients are diagnosed with chronic insomnia.1 Patients have reported restlessness, trouble falling asleep and increased sleep-wake hours throughout the night. Compounding with the emotional stressors such as anxiety and depression and typical cancer pains, the effects of chemotherapy are physically strenuous and debilitating. Many issues arise from an inadequate amount of sleep. Starving the body of this vital repair period is detrimental cognitively, physically, and biologically. During sleep, the body undergoes a system of hormone release and inhibitions necessary for repair and information storage. Research has shown that, when left untreated, chronic insomnia, leads to daytime fatigue and depressive behaviors.2 Many patients who experience chronic insomnia also exhibit impaired mood and reduced energy levels, and are more likely to be diagnosed with clinical depression. Immune function, which is often already suppressed because of certain chemotherapy drugs, becomes compromised with of lack of sleep, leading to an increased risk of disease and infection for the patient. The potential causes of insomnia include family history, anxiety or depression, advanced age, and female gender. In addition, certain medications, including chemotherapy, radiation, and hormone therapy are linked to insomnia during cancer treatment. Sleep disturbances are exacerbated during chemotherapy due to a negative effect on the endocrine system causing neuroendocrine disruptions that cause insomnia.3 Further, the natural aging process lends itself to prolonged sleep-onset latency and sleep maintenance. The increase in cancer diagnoses later in life,4 highlights the necessity to investigate ways to improve sleep quality and limit the damaging effects of sleep deprivation.

Many treatment options have been explored to treat sleep disturbance and deprivation. In fact, Approximately 25%–50% of all prescriptions written for patients with cancer are for hypnotics.5,6 However, the vast majority contain side effects that interfere with quality of life, including residual next day effects, toxicity when combined with other sedating agents, risk of dependence, and rebound insomnia when stopped.5 One possible non-pharmacologic treatment that may help offset the negative effects of sleep disturbance is exercise. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) asserts that moderate exercise has no harmful effects on cancer patients. In fact, decades of research support the use of exercise to improve mood, increase energy, increase strength, and build immunity. Further, patients who participate in regular exercise have reported up to 50% less fatigue during chemo-treatments. As such, the NCCN recommends approximately 150 minutes of moderate cardiovascular exercise each week along with 2 to 3 weekly sessions of strength training. In addition, regular stretching of major muscle groups will aide in mobility and reduce risk of injury.7 However, research on the effectiveness of exercise in reducing sleep deprivation during cancer treatment is scant. Therefore, the purpose of the present investigation was to examine the role of prescribed, individualized exercise in mitigating sleep disturbance associate with cancer treatment.

Subjects

This controlled trial evaluated the effects of individualized exercise therapy in 253 patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment. Oncology patients who received cancer treatment at Soin Medical Center in Dayton, Ohio between March 6, 2018–June 26, 2018 participated in a cancer exercise program through Maple Tree Cancer Alliance, a non-profit organization that provides free exercise training to individuals battling cancer. The age range of the patients was 24-68 years. Study participants underwent standard prescribed chemotherapy schedules (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluroracil, adriamycin, and cyclophosphamide). Patients were excluded from the study if they had pre-existing cardiac, liver, and bone marrow conditions prior to treatment.

Measures

At the initial visit, demographic information, medical history, and relevant clinical data were ascertained from all consenting participants. Patients then completed the Sleep Condition Indicator, which was used to gauge the severity of sleep disturbance and deprivation related to chemotherapy. The checklists consisted of 9 items of severity graded from 0-4, with qualifiers given for severity (i.e. How long does it take for you to fall asleep? 0-15 min = 4 points, 16-30 min = 3 points, 31-45 min = 2 points, 46-60 min = 1 point, >60 min = 0 points). These scales measured the total sleep deprivation and disturbance and severity score.

Patients also underwent a comprehensive fitness assessment at this time. Cardiovascular fitness was measured via the Bruce treadmill test. Muscular strength was measured via hand grip dynamometer. Modified sit and reach measured flexibility. Muscular endurance was assessed via partial curl up test, and body composition was measured using skinfold calipers. Results from this fitness assessment were used to create an individualized exercise program that focused on each patient’s strengths and weaknesses.

Exercise training protocol

Each patient participated in a cancer exercise program through Maple Tree Cancer Alliance. All interested patients were referred by hospital oncologists, and began participation in the exercise program upon referral. They completed 12 weeks of prescribed, individualized exercise that included cardiovascular, strength training, and flexibility components during chemotherapy treatment. The intensity level for the cardiovascular exercise ranged from 30-45% of the individual’s predicted VO2max. The strength training involved a full body workout, with emphasis on all major muscle groups. Machines, free weights, and tubing were all employed. Patients completed 3 sets of 10 repetitions for each exercise. Flexibility training involved static stretching of all major muscle groups for 15-20 seconds at the completion of each workout. Patients met with a trainer once a week and were given instructions on how to remain active at home. At the conclusion of this 12-week exercise program, patients underwent a follow-up reassessment and completed the ESAS-R) questionnaire and subjective symptom checklist again.

Statistical method

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 20.0 for PC windows 2000. Mean scores for measured sleep disturbance and fitness parameters were calculated for the complete sample. Since order of adjuvant treatment differed, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was done to compare groups at each follow-up assessment using the baseline pre-chemotherapy measure as a covariate. A significance level of p<0.05 was used for all statistical analyses.

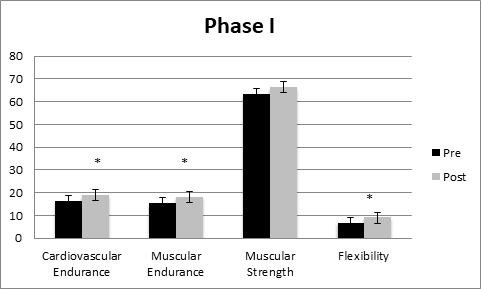

A total of 253 patients currently undergoing cancer treatment completed the study. Table 1 presents patient demographics. Twelve weeks of supervised, individualized exercise had a positive impact on fitness parameters as well as sleep. Muscular strength, muscular endurance, and cardiovascular endurance also significantly improved from baseline (p<0.05, Figure 1).

Figure 1 Phase I program completers from pre-post-exercise programming. Values are mean scores + SE, VO2 in ml/kg/min, muscular endurance in repetitions, muscular strength in psi, flexibility in inches (n=253). *p<0.05.

Average Age (years) |

60 + .05 |

|

Gender |

||

Male |

15% |

|

Female |

85% |

|

Ethnicity |

||

White |

70% |

|

African American |

13% |

|

Hispanic |

4% |

|

Asian |

5% |

|

Unknown |

8% |

|

Type of Cancer |

||

Breast |

61% |

|

Colon |

3% |

|

Prostate |

2% |

|

Lung |

4% |

|

Leukemia |

1% |

|

Brain |

1% |

|

Multiple Myeloma |

4% |

|

Table 1 Patient demographics

On average, patients who participated in prescribed, individualized exercised saw significant improvement to their sleep Table 2.

Pre-score Average |

Post-score Average |

Percent Change |

|

How long does it take you to fall asleep? |

47.5 min |

33.89 min |

75.15%8 |

If you wake up one or more times during the night, how long are you awake in total? |

41.4 min |

22.12 min |

90%8 |

If your final wake-up time occurs before you intend to wake up, |

58 min |

31.2 |

160.61%8 |

How many nights a week do you have problems with your sleep? |

2.21 |

3.33 |

50.68% |

How would you rate your sleep quality? |

2.11 (Average) |

3.41 (good) |

61.61%* |

Thinking about the last month, to what extent has poor sleep affected your mood, |

2.42 (Somewhat) |

3.81 (A little) |

57.44% |

Thinking about the last month, to what extent has poor sleep affected your |

1.72 (Very much) |

3.01 (A little) |

75%* |

Thinking about the last month, to what extent has poor sleep troubled you in general? |

2.78 (Somewhat) |

3.71 (A little) |

20.45% |

Table 2 Presents the questions in the survey, average pre-post scores and percent change (n= 253, *p<0.05)

Insomnia is a common problem for cancer survivors. It can present as difficulty falling asleep, waking throughout the night, or awakening early in the morning with the inability to fall back to sleep. Sleep disturbance and deprivation, as well as their associated pharmacological therapies, have side effects that can have a negative impact on an individual’s quality of life. Thus, the purpose of the present investigation was to examine the role of prescribed, individualized exercise in mitigating sleep disturbance associated with cancer treatment. On average, we found that patients who participated in prescribed, individualized exercised saw significant improvement to their sleep. Physiologically, sleep is a process that is internally and externally controlled by an interaction of the circadian clock and homeostatic mechanisms.8 Internal factors include intrinsic mechanisms that moderate metabolic circadian rhythms. These molecular mechanisms involve transcription feedback loops that produce proteins within a cell,8 and function to classify sleep into two states: rapid eye movement sleep (REM sleep) and non-REM sleep. Non-REM sleep is subdivided into three stages, N1, N2, and N3, with N1 as the stage that lies between wake and sleep, N2 being a slightly deeper stage of sleep, marked by a higher auditory arousal threshold and changes in brain activity, and N3 as slow-wave sleep, with low-frequency, high-amplitude brain activity.8 Fatigue is highly prevalent in patients with cancer. Although cancer-related fatigue and cancer-related sleep disorders are distinct, a strong interrelationship exists between these symptoms. Studies that have assessed both sleep and fatigue in cancer survivors reveal a strong correlation between cancer-related fatigue and various sleep parameters, including poor sleep quality, nighttime awakening, restless sleep, a disrupted initiation and maintenance of sleep, and excessive daytime sleepiness.9–11 In adults, the effects of chronic and acute exercise on sleep are strongly correlated. In a meta-analysis by Kredlow et al.12 both acute and regular exercise were found to have a positive effect overall.12 REM sleep has important metabolic consequences due to the reported increase in metabolic rate and glucose utilization during this stage of sleep.13 Alley et al.14 found that the timing of resistance exercise did not significantly affect total or REM sleep the following evening,14 but regardless of the time of day, engaging in resistance exercise did improve sleep quality. Specifically, variations in the timing of resistance exercise impacted sleep onset latency and wake time after sleep onset. Further, Harp et al.15 evaluated the chronic effects of exercise on sleep in young adults15 and found that body composition (positively impacted by exercise) was significantly related to sleep quality.

Sleep disorders are a common and often chronic problem for cancer survivors. Until recently, such symptoms have been scarcely researched. Current understanding of the possible link between cancer related fatigue and sleep disturbances suggests that interventions targeting disordered sleep could provide promising potential treatments.16 Given the emerging data that suggest cancer-related sleep disturbance is commonplace, and that it may be interrelated with symptoms of daytime fatigue, it follows that targeted treatment of either symptom may positively affect the other. This and other data point to physical exercise as an effective intervention for those with sleep disturbance and deprivation. Further investigation is warranted in order to better understand the nature of sleep disturbances, the complex relationship they have with CRF, and their association with other symptoms commonly reported by patients with cancer, such as depression, pain, and anxiety. Despite the overwhelming evidence that adequate exercise is a necessary component for optimizing patient health, less than 5% of cancer patients exercise during cancer recovery.17 Therefore, it is our recommendation that prescribed, individualized exercise should serve as part of the national standard of care for all those diagnosed with and treated for cancer.

None.

Author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2020 Wonders, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.