eISSN: 2577-8285

Opinion Volume 2 Issue 4

Department of Medicine, International Centre for Healthcare and Medical Education (ICHME), UK

Correspondence: Department of Medicine, International Centre for Healthcare and Medical Education (ICHME), Bristol, UK

Received: July 29, 2018 | Published: August 21, 2018

Citation: Lazzari C, Rabottini M. Healthcare organizations and sleep deprivation. Is adequate sleep still granted to healthcare workers? Sleep Med Dis Int J. 2018;2(4):100-101. DOI: 10.15406/smdij.2018.02.00051

Modern-day healthcare organizations strive to provide sufficient protection to healthcare workers concerning their time of recovery sleep. Instead, the progressive reduction of staff, the problem of filling temporary vacancies and rotas, and the urgent requirements of on-calls put extra stress on healthcare workers who might borrow time from their sleep hours to stretch their working time. However, this organizational habit might impact on professional liability of healthcare workers who cannot get enough sleep while involuntarily making them more vulnerable to professional errors. The current article examines the theories that link productivity to working hours and recovery sleep in the healthcare services.

Keywords: serotonin, healthcare, sleep, productivity, organization, professional errors

Inadequate amount of sleep is a universal characteristic of contemporary culture.1 Besides, insufficient sleep in healthcare workers can lead to medical errors and questions on the professional liability of those who were aware of their reduced sleeping hours.2,3 The current article will explore some theories in healthcare organizations which unwillingly have conducted to altered sleep patterns in healthcare workers. Some identifiable causes of the ‘sleep problem’ in the healthcare professions are the national shortage of healthcare workers, the need to fill unexpected gaps in the shifts, the urgency to provide coverage for on-call rotas, and the financial incentives provided to healthcare workers who borrow hours for work from their sleep time.

Although reduced sleep is recognized by many as being a matter of concern for healthcare workers, there seems to be little progress in the healthcare management to improve working hours, understaffing of hospital wards, an increased workload with reduced recovery sleep, work-related stress, and employees’ insomnia. One obvious consequence is that staff will try to neutralize the ongoing tiredness and reduce the need for sleep by using caffeine-containing drinks which also reduce the pressure to sleep. Other times, the overuse of energy-containing food or drinks can somewhat impair normal metabolism and conduce to carbohydrate overload to feel less the exigency to sleep. Nonetheless, the typical consequence is a background variation of the sleep-modulating neurotransmitters (e.g. serotonin and dopamine) which will be conducive to altered sleep once the physiological sleep pattern is restored. There is another aspect which often escapes from surveys about the consequences of poor sleep on medical error: professional accountability. On one side, healthcare organizations are struggling against a progressive reduction of staff. Similarly, healthcare managers need to have more night shifts covered by stretching working hours of healthcare workers who have already stayed during day shifts. As lumps provide the total weekly working hours, it is likely that some healthcare professionals might have shifts longer than eight or more hours with unexpected impact on their sleep patterns and work efficiency. This last event is rarely studied in modern healthcare management. Sometimes, healthcare managers are pressed to cover gaps in working shifts by using the same number of personnel. This occurrence will induce some employees to accept a reduction of sleep hours to help with vacant shifts. The authors of the current communication found some uncertainty in hospital managers to reflect on the risk of jeopardizing professional liability in their employees by asking them to work beyond the eight hours daily, in night shift, and in reducing their hours of (recovery) sleep. Similarly, a shared attitude brings many healthcare workers to hide their desire to have more sleep hours not to appear ‘lazy’ to their employers. Hence the comments ‘feeling sleepy’ and ‘wanting to sleep more’ are still considered in some organizations and by some employees as signs of professional ‘weakness’ to be managed somehow. This organizational behavior in some way resembles Fordism which aims to higher output with lower costs.4 Furthermore, this trend has translated in the attitude of some healthcare managers to ask extra working hours to their staff, using the same personnel for daytime and night shifts, while giving financial incentives to those who volunteer to work more and thus to sleep less. As reported by several professional bodies, healthcare workers sleep less than standard population while using caffeine-based drinks to stay awake.5 Despite the awareness of poor sleep in healthcare employees, hospital managers still have a lack of personnel to cover their shifts. Alarms are raised in the website community more than in specialized literature. For instance, The National Sleep Foundation recommends an average of seven to nine hours sleep for working-age adults of 18 to 65.6 According to research, actual sleep patterns resemble those found in ancient civilizations and pre-industrial society where sleep was regulated by things to do more than the hours allocated.7 The same occurs for healthcare workers, nurses and doctors working during night shifts which have their sleep interrupted by urgent calls, patient’s deteriorating conditions, and other emergencies to attend. Hence, a mix of lack of sleep and interrupted sleep remains as the standard pattern in modern healthcare working conditions. From ethnographic observations, the authors of the current article could distinguish several patterns in the altered sleep of healthcare employees:

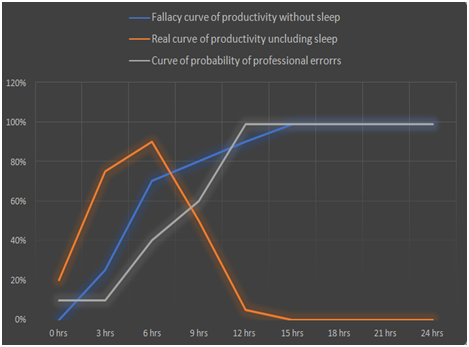

The Office for National Statistics defines productivity also as production per individual employee.9 When linking work productivity to the number of working hours, the authors of the current study designed curves explaining the manager’s fallacy and the real course in calculating efficiency in the healthcare productivity (Figure 1). The misconception consists in assuming that productivity is directly linked to the number of hours worked, hence, linking the outcome to the twenty-four-hour cycle (Figure1). Instead, the real curve of productivity does include recovery sleep into the equation thus providing a peak for work efficacy and productivity constrained into the regular five to eight working hours. Afterward, sleep pressure counteracts work productivity while increased sleep deprivation lowers efficiency and increases the likelihood of a professional’s errors. In other words, sleep too enters the equation for job productivity for every single worker (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Fallacy and right curve of productivity excluding and including sleep hours and curve of the likelihood of professional errors (expressed as percentages). At the point of crossing (6hours), healthcare management might consider that extra working hours borrowed from employee’s sleeping hours will not impact on workers’ productivity. Instead, our study hypothesizes that productivity has a steep decline after six to eight hours of work with an increased likelihood of reduced job productivity and increased likelihood of professional errors.

Fallacy and right curve of productivity excluding and including sleep hours and curve of the likelihood of professional errors (expressed as percentages). At the point of crossing (6hours), healthcare management might consider that extra working hours borrowed from employee’s sleeping hours will not impact on workers’ productivity. Instead, our study hypothesizes that productivity has a steep decline after six to eight hours of work with an increased likelihood of reduced job productivity and increased likelihood of professional errors (Figure 1).

The current communication highlights some of the drawbacks inherent in a healthcare model operating on outcome measures but relying on a limited number of human resources and involuntarily reducing planned sleep breaks for healthcare workers. One consequence of the mounting pressure to cover shifts and vacancies in the healthcare services with no personnel is to ask current staff to cover extra-shifts at the expenses of their sleep time. As seen in the current study, the promotion of this habit originates from an apparent fallacy in the managerial theory which assumes that individual and organizational productivity can increase by accretion of working hours. This position does not consider recovery sleep as being central to the productivity equation. Instead, work efficiency drops soon after five to eight hours of work with increased risks of professional errors if employers do not grant proper recovery sleep to individual workers.

©2018 Lazzari, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.