eISSN: 2576-4543

Research Article Volume 9 Issue 1

Science Education Department, Facultad Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Argentina

Correspondence: Guillermo Cutrera, Science Education Department, Facultad Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina, Funes 3350, CP: 7600

Received: January 06, 2025 | Published: February 12, 2025

Citation: Cutrera G. Reflective writing and teaching electrical circuits: a study on the development of reflective practice in pre-service teacher education. Phys Astron Int J. 2025;9(1):17‒27. DOI: 10.15406/paij.2025.09.00359

This study analyzes the reflections written by a pre-service physics teacher on his teaching intervention in teaching electrical circuits in a secondary school. Four levels of reflective depth were identified: descriptive (43%), comparative (31%), critical (17%), and emotional self-assessment (9%). In addition, associated epistemic emotions, such as frustration, pride, and insecurity, and their influence on pedagogical decisions were explored. The results highlight how reflective writing facilitates the connection between theory and practice, allowing teachers to integrate macroscopic and submicroscopic levels in their teaching. However, challenges were also evident, such as cognitive complexity for students and technical problems with teaching resources. This work contributes to pre-service teacher education by addressing gaps related to the impact of epistemic emotions on reflective development and the transition from descriptive to critical levels. Methodologically, a qualitative approach based on thematic content analysis was used, providing an interpretive framework transferable to similar contexts. The findings suggest practical implications for designing training strategies promoting more profound and transformative reflection.

Keywords: teacher reflection, reflective writing, epistemic emotions, initial teacher training, teaching of Physics

Teaching reflection is an essential component in teacher initial training, as it allows them to analyze and redefine their classroom experiences to improve their pedagogical practices. However, despite its relevance, important gaps persist in research on how certain factors, such as epistemic emotions and reflective writing, influence the reflective development of future teachers. These gaps limit understanding of how effective training strategies can be designed to promote critical and transformative reflective practice.

First, although epistemic emotions have been recognized as a key component in teaching learning and practice,1,2 their specific impact on the reflective process of future teachers remains an underexplored area. Emotions such as frustration or pride can significantly influence how teachers process their experiences and make pedagogical decisions. However, more research is needed to understand how these emotions directly affect critical reflective development.3,4

On the other hand, reflective writing has been highlighted as a valuable tool to foster systematic reflective practice.5,6 However, few studies have specifically analyzed how this practice can facilitate the transition from descriptive to critical levels of reflection. Rusznyak7 points out that although reflective writing helps teachers document their experiences, there is a lack of research exploring how this tool can promote transitions to deeper forms of critical analysis. Similarly, Lionenko, M. and Huzar8 emphasize that more empirical evidence is required on the factors that facilitate or limit the effectiveness of reflective journals in developing critical skills. In this context, the present work aims to analyze the reflections written by a future physics teacher about his teaching intervention in teaching electrical circuits in a secondary institution. This analysis seeks to identify the levels of reflective depth in the teacher's narratives, the emotions associated with the reflective process, and the connections between theory and practice. This approach intends to understand how these dimensions impact the future teacher's immediate pedagogical decisions and their long-term professional development.

This study addresses the gaps mentioned above and contributes to the field of initial teacher education by offering an interpretive framework to analyze how future teachers process their educational experiences. Furthermore, it provides empirical evidence on the central role of epistemic emotions and reflective writing in developing a critical and informed teaching practice. This study expands the theoretical understanding of these issues and offers practical implications for designing training strategies that promote more profound and transformative reflection among future teachers.

Methodologically, this research adopts a qualitative approach based on thematic content analysis,9 which allows for identifying significant patterns in future teachers' written narratives. This approach is particularly suitable for exploring complex phenomena such as teacher reflection and its relationship with epistemic emotions. The results are organized around three main dimensions: levels of reflective depth, emotions associated with the reflective process, and connections between theory and practice. The work is structured in several sections. First, a conceptual framework on teacher reflection and initial training is presented. Next, the methodology used to analyze the written narratives of future teachers is described in detail. Subsequently, the results are presented and discussed in light of previous research. Finally, it synthesizes the main findings and practical implications for the educational field.

Teacher reflection in initial teacher trainingTeacher reflection is an essential component in the initial training of future teachers, as it allows them to analyze and redefine the experiences lived in the classroom. However, this concept is intrinsically polysemic and has been interpreted from multiple perspectives in educational literature. According to Dewey,10 reflection is an intellectual and emotional process that helps teachers understand and solve complex problems in their practice. This approach was expanded by Schön,11 who introduced the concepts of reflection-in-action (reflection during action) and reflection-on-action (reflection after action), highlighting how teachers can learn both at the time of practice and by reviewing it afterwards.

In this work, reflection is understood as a multidimensional process that integrates cognitive, emotional and contextual aspects, allowing teachers to adjust their pedagogical strategies and develop a critical and transformative professional identity.12 This perspective is aligned with recent studies that emphasize that reflection is not only a technical or instrumental process but also a critical act that allows us to question pedagogical practices and the social structures that support them.13,14 In this sense, reflection facilitates the adjustment of teaching strategies and promotes the development of a critical and transformative professional identity.

Initial teacher training is designed to provide future teachers with the necessary skills to perform their professional roles in diverse educational contexts.15 This period is crucial because it lays the foundation for developing teaching, reflective, and emotional skills that will be fundamental throughout their careers.16 In this context, reflection becomes a key tool to connect theory and practice, allowing preservice teachers to integrate theoretical knowledge with practical experiences in the classroom.17

A central aspect of initial teacher training is using reflective writing to foster systematic reflective practice. According to Harrison et al.,5 reflective writing allows for documenting experiences and exploring thoughts and emotions associated with them, facilitating deeper learning. This study uses reflective writing to analyze how a preservice teacher processes his or her classroom experiences, connects these experiences with relevant theoretical frameworks, and proposes concrete improvements for his or her pedagogical practice. This practice helps preserve teachers identify teaching patterns, question their pedagogical decisions, and propose concrete improvements. Furthermore, recent research highlights that reflective writing can bridge emotions and teaching decisions, helping teachers manage negative emotions such as frustration or insecurity and transform these experiences into learning opportunities.1 Reflective writing also plays a fundamental role in facilitating connections between theory and practice. Farrell18 argues that this tool allows teachers to integrate theoretical concepts into their reflective analysis, facilitating a deeper understanding of teaching problems and more informed decision-making. For example, recent studies have shown that preservice teachers who regularly engage in reflective writing activities are more likely to develop critical skills to analyze their practices from multiple perspectives.6

Different research highlights three key dimensions related to the aim of the study: the levels of reflective depth, the emotions associated with the reflective process, and the connections between theory and practice. Regarding reflective levels, recent studies confirm that preservice teachers tend to focus initially on descriptive levels before moving towards critical reflections.19 For example, Lara Subiabre20 found that descriptive reflections predominate in preservice teachers' narratives due to their inexperience and the initial need to document what happened. However, research by Schlein21 and Noble22 underlined that reaching critical levels is essential to transform teaching practice, as it allows questioning of immediate pedagogical decisions and social and cultural structures that influence them.

Emotions associated with the reflective process have received increasing attention in recent literature. Hernández del Barco et al.1 introduce the concept of "epistemic emotions," referring to feelings associated with knowledge construction. These emotions—such as frustration or pride—can significantly influence how teachers process their experiences and make pedagogical decisions. Pekrun et al.2 highlight that negative emotions can temporarily limit a teacher's reflective capacity and act as catalysts for future changes if managed appropriately.

Finally, connections between theory and practice are critical to understanding how preservice teachers integrate conceptual frameworks into their teaching. Reflective writing and reflection are critical to bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application for preservice teachers.23,24 This process is essential to integrating conceptual frameworks into teaching practices, as it fosters self-analysis, critical thinking, and ongoing professional development. Reflective skills are a component of professional competence and a dynamic process involving stages of formation and requiring awareness and readiness for change.25

In the context of the connections between theory and practice, the distinction between levels of conceptualization is recovered in this work. Taber26 underlines the importance of carefully transitioning between different conceptual levels - macroscopic, submicroscopic and symbolic - to facilitate meaningful learning in science. This approach is particularly relevant in the present study, where the future teacher sought to integrate these levels to teach electrical circuits. Taber27 expands on Johnstone's28 "chemical triplet" model, which organizes the levels of representation in science teaching. This model includes three primary levels:

Taber27 highlights that effective learning in science requires moving between these levels to build an integrated understanding. He also underlines the importance of connecting the macroscopic and submicroscopic levels through appropriate technical language, leaving the symbolic level as a complementary tool to facilitate scientific understanding and reasoning. The future physics teacher recovered this distinction between levels of conceptualization in his analyses.

Conceptual justification of the system of reflective categoriesThis work developed a system of reflective categories to analyze teachers' narratives from different levels of depth and emotional dimensions. The constructed system integrates key theoretical contributions to capture the complexity of the reflective process. In particular, it is based on the typology proposed by Jay and Johnson,13 who identify three primary levels of reflection: descriptive, comparative and critical. These levels allow the analysis of how teachers progress from a basic description of the facts to deeper questions about their practice's ethical, social and political implications. The proposal presented is aligned with the idea of a progression in the levels of reflection, as proposed by Van Manen,29 Larrivee14 and Jay and Johnson.13 This group of authors agree that reflection begins at basic levels, such as description or technical analysis, and progresses towards more complex forms, including ethical, social and political questions.

Descriptive reflection focuses on narrating what happened without delving into its causes or consequences. This level is common in future teachers, who document their initial experiences to organize their practice.30 Comparative or dialogic reflection, on the other hand, introduces a more elaborate analysis by considering alternative perspectives or educational theories to interpret the observed problems. The category "dialogic reflection" in this proposal is directly inspired by Hatton and Smith,30 who identify this level as an internal dialogue or deliberative exploration of reasons. This type of writing is also found in Farrell,18 who emphasizes how teachers reflect on their professional identity through dialogue with themselves and others. Finally, critical reflection involves deep questioning that transcends the technical to address broader ethical and social issues. Critical reflection is an essential component in all the reviewed classifications, including those proposed by Jay and Johnson,13 Van Manen29 and Larrivee.14 This level allows prospective teachers to question their practices and the social, political and cultural structures that influence them. Jay and Johnson13 highlight how this reflection fosters a comprehensive understanding of the problem by considering ethical and social implications. Larrivee14 emphasizes that this level requires teachers to challenge their beliefs and consider new perspectives to transform their educational practice.

In addition to these levels, the system incorporates an emotional dimension based on recent research on the role of emotions in teaching practice.20 Emotional self-assessment is a specific category that analyzes how teachers recognize and manage their emotions in critical incidents or pedagogical challenges, according to Zhao et al.31 According to Arefian et al.,32 emotions directly affect teaching decisions and teachers' perceptions of their performance. For example, negative emotions can temporarily limit a teacher's reflective capacity33 but also act as catalysts for future changes if managed appropriately.32 In the analyzed case, these emotions were key to understanding how the future teacher processed critical incidents related to technological resources and planning.

The inclusion of this emotional dimension responds to the need to address the cognitive aspects of the reflective process and its affective component. Epistemic emotions1 -feelings associated with knowledge construction- are especially relevant in educational contexts where teachers face uncertainty or complex conceptual challenges. For example, in the analyzed text, the future teacher expressed technical insecurity when using testers during a practical activity. This recognition evidences a mixed emotion (insecurity) and an effort to redefine the experience to improve future interventions.

Finally, the proposed category system is aligned with methodological approaches focused on critical incidents.34 Critical incidents are significant events that generate tensions or conflicts in teaching practice and require deep reflection to understand and overcome. In this framework, reflective categories allow us to analyze how teachers describe these incidents (descriptive reflection), identify their causes (comparative reflection), and propose transformative solutions (critical reflection).

MethodologyThe present study adopted a qualitative approach based on the analysis of an instrumental case. This decision is framed because the research sought to explore and understand the reflections written by a future physics teacher on his teaching practice. This approach allows for an in-depth analysis of the narrated experiences, identifying patterns, meanings and levels of reflection that emerge from the text (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). According to Stake,35 instrumental cases are used when the main interest lies not exclusively in the case itself but in how it can provide a broader understanding of a specific phenomenon or topic. In this context, the case analyzed - a future physics teacher reflecting on his teaching intervention in the teaching of electrical circuits - acts as a tool to explore the dynamics between reflective writing, epistemic emotions and teacher professional development. The use of an instrumental case is particularly suitable for this study because it allows for a deeper look into the individual experiences of the prospective teacher, identifying patterns and meanings that may be transferable to similar educational contexts.36 This approach seeks not statistical generalizations but a rich and contextualized understanding that can inform educational theory and practice.37 Furthermore, choosing a single case allows for a detailed and in-depth analysis of the participant's reflective narratives, essential to capture the complexity of the reflective process and its relationship to epistemic emotions.

The case corresponded to the reflections written by a prospective physics teacher who documented his experience during a teaching intervention focused on teaching electrical circuits at a secondary school. The intervention spanned three consecutive classes, during which the teacher integrated macroscopic and submicroscopic levels to address concepts such as electric current, resistance, and voltage. This decision reflected his intention to overcome perceived limitations in a previous intervention and give students a deeper understanding of electrical phenomena. She documented her experiences, pedagogical decisions, and emotions associated with critical incidents during the intervention through her reflective writing. The lesson planning included activities designed to integrate both conceptual levels. For example, in the first class, she used an analogy based on ramps and marbles to explain the flow of electrons at a submicroscopic level. In the second class, students participated in a practical experience where they assembled electrical circuits using physical components. This activity allowed them to connect previously worked-on concepts with their macroscopic representation. Finally, in the third class, she presented Ohm's Law using a simulator and group activities.

The case analysis focused on identifying significant patterns in the teacher's written reflections, considering both their practice's cognitive and emotional aspects. This approach allowed us to understand how the participant processed their educational experiences and generate transferable insights that can inform training strategies in initial teacher training. The content analysis technique was considered appropriate for this type of study since it facilitates the identification, organization and systematization of the themes and categories present in the qualitative data.9

The thematic content analysis was developed following the three main stages proposed by Bardin.9 In the pre-analysis, the objectives of the analysis were defined, and the textual corpus to be studied was selected. The future teacher's reflective text was segmented into meaningful units, understood as fragments that contained complete ideas related to teaching practice. This segmentation allowed the analysis units that would be subsequently coded to be delimited. In addition, reflective categories were established based on a pre-existing theoretical framework.13,20,30 Each category was applied to the reflective text using a systematic approach:

The analysis was also structured around critical incidents.34,39,40 These incidents—such as technical problems with the simulator or difficulties with the testers—were used as key points to analyze how emotions and reflective levels interacted in pedagogical decision-making. The text was coded using a systematic process in the stage corresponding to the exploration of the material. Each significant unit was assigned exclusively to a reflective category. In these terms, each fragment exclusively reflected a predominant level of reflection, avoiding overlaps between categories. Identifying predefined categories and emerging themes related to the challenges and achievements of the teacher in training was allowed. Representative textual quotes were recorded to support each coding.

In the treatment and interpretation stage, the data obtained were analyzed to identify significant patterns in the reflections of future teachers. This analysis included two different instances. On the one hand, thematic identification: the coded units were grouped according to the main emerging themes of the reflective text (for example: "levels of conceptualization", "use of analogies", "challenges with teaching resources"). On the other hand, the quantification of frequencies: Each reflective category's absolute and relative frequency was calculated to identify its predominance in the analyzed text. Quantification followed a systematic procedure based on the initial segmentation of the text into meaningful units, exclusive assignment of each unit to a reflective category, and detailed recording of frequencies for each category.

From a qualitative perspective, using a single case study does not have statistical generalization as its primary objective but is oriented towards a naturalistic generalization.35 Naturalistic generalization is based on the idea that qualitative results are valuable not for their statistical representativeness but for their ability to generate transferable insights.37 This approach seeks to provide a deep and contextualized understanding of the phenomenon studied, allowing readers to evaluate the transferability of the findings to other similar contexts.

Different strategies were adopted to ensure the validity of the analysis. Theoretically, theoretical triangulation was used: the categories were based on multiple relevant theoretical frameworks.13,20,30 On the other hand, an iterative review was carried out by developing successive revisions to adjust the initial codifications. In this work, triangulation between researchers41 was implemented through consultations with expert colleagues in science education and qualitative analysis. Finally, in the context of a longitudinal analysis, changes in reflections over time were analyzed to identify progressions towards more critical levels.

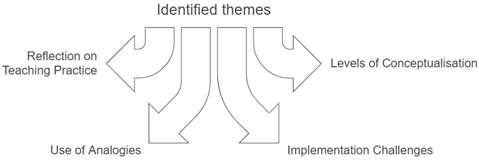

Analyzing the future physics teacher's reflections allowed us to identify four main themes: reflection in teaching practice, levels of conceptualization in teaching, analogies in physics teaching, and challenges in implementing teaching resources (Figure 1). Each of these themes is expanded upon below.

Figure 1 The main themes identified in the text prepared by the future teacher.

Source: Own elaboration.

Reflection in teaching practice

Reflection was presented as an essential component to analyze and improve teaching practices. The future teacher highlighted that reflecting on his experience allowed him to explore thoughts and feelings related to specific situations, facilitating a deeper understanding of his intervention. In his words: "Reflection is an essential part of teaching, as it allows the teacher to look beneath the surface of his experience, in order to explore his thoughts and feelings in the face of situations or problems related to his work." This approach highlights the importance of looking beyond the facts to identify achievements and drawbacks in teaching.

In addition, she pointed out how reflection allowed her to evaluate the effectiveness of her teaching strategies: "I find that reflecting on my practice helped me identify which decisions were correct and which ones generated difficulties for students, especially when working with submicroscopic levels." This coincides with what was proposed by Alnijres,42 Nazir et al.,43 and Hatton and Smith,30 who argue that reflection allows teachers to connect their experiences with future teaching decisions, promoting continuous learning.

Levels of conceptualization in physics teaching

The content of the text prepared by the future teacher addresses the importance of macroscopic and submicroscopic levels of conceptualization in teaching physics concepts, such as electrical circuits. It considers how these levels affect students' understanding and how teachers should balance both to facilitate learning. Teaching at the submicroscopic level can offer a more profound understanding but can also complicate learning if not appropriately managed ("Learning Physics Concepts in Secondary Education Classrooms, 2017"). "It is partially linked to the complexity with which teachers decide to work with them").

Using analogies in teaching physics

The use of analogies was identified as a key strategy to facilitate understanding abstract concepts. The author used an analogy based on ramps and marbles to explain the flow of electrons: "Through an experience with Hot Wheels ramps and marbles, I generated an analogy to electrons moving [...]. This analogy was beneficial to work at the submicroscopic level." This strategy allowed students to visualize phenomena that were not directly observable.

However, he also recognized limitations in analogies: "Some students did not fully understand the idea and took the example very literally, so they could not associate the analogy with the concepts very well." This comment highlights the need to carefully select analogies and accompany them with clear explanations to avoid misunderstandings. According to Mortimer and Scott (2002), analogies are powerful tools for constructing scientific meanings as long as they are used within an appropriate discursive framework.

Challenges in the implementation of teaching resources

The text describes several challenges related to the practical use of teaching resources such as testers and simulators. For example, the future teacher faced technical problems when using a simulator: "When we put the simulator on a SmartTV [...], we noticed that it did not represent the HTML5 of the simulator well [...]. This generated a feeling of frustration and demotivation in me." This critical incident affected his emotional disposition and ability to continue the planned activities.

Likewise, technical difficulties were identified when using testers during practical activities: "The testers recorded 'strange' values in the electrical circuits made by the students [...]. This generated confusion because the values did not comply with Ohm's Law." These experiences led the future teacher to reflect on improving his technical preparation and adapting activities to unforeseen problems: "Next time, I would dedicate a special time to explain how the tester works and how to measure the variables correctly."

These challenges reflect what Chin-Yee44 and Akdağ45 have pointed out, highlighting that technical limitations are often a frequent source of critical incidents during teaching practices. However, they also represent valuable opportunities to develop reflective and adaptive skills.

Distribution of reflective categories: quantitative analysis of frequenciesThe frequencies associated with each of the categories corresponding to writing are presented in Table 1.

|

Reflective Category |

Absolute Frequency |

Relative Percentage |

|

|

Descriptive reflection |

30 |

43% |

|

|

Comparative/dialogic reflection |

22 |

31% |

|

|

Critical reflection |

12 |

17% |

|

|

Emotional self-assessment |

6 |

9% |

|

Table 1 Frequencies of occurrence for each of the writing categories

Source: Own elaboration

The analysis of the future physics teacher's reflections, based on a model that classifies the levels of reflective depth, allowed us to identify significant patterns in his reflective practice. This approach focused on four main categories: descriptive reflection, comparative/dialogic reflection, critical reflection, and emotional self-assessment, each representing a different degree of analysis and depth in interpreting the teaching experience.

For example, the author describes his intervention at school as follows: "In the second class, the students built electrical circuits with various components, applying previous theoretical knowledge and understanding how to connect elements to generate the flow of electric current through a practical experience." This fragment is representative of a descriptive reflection because it limits itself to narrating what happened in the classroom without analyzing the challenges faced or the pedagogical decisions that influenced the development of the activity.

Another clear example appeared when he detailed his initial planning: "In the first class, I reviewed the definition of kinetic energy and potential energy to work with the definition of mechanical energy, associating it in the process with everyday life situations." In this case, the preservice teacher described how he structured his class and the concepts addressed without going into depth about the reasons behind his methodological choices or how these impacted student learning.

Furthermore, this type of reflection was evident when mentioning technical problems during classes. For example, "When we put the simulator on a Smart TV, we noticed that the TV itself did not properly represent the simulator's HTML5. For this reason, the application was not displayed correctly." Although a specific problem is identified here, its broader implications are not explored, and alternative solutions are not proposed.

In addition, the future teacher reflected on critical incidents related to using the simulator and its impact on the levels of conceptualization worked on. For example, he noted: "Due to technical problems with the simulator, an activity planned to be worked on at a macroscopic level was now worked on at a submicroscopic level [...] This generated additional difficulties for students when trying to associate abstract concepts." This analysis shows how he linked his practical experiences with didactic perspectives to identify problems and propose concrete solutions.

The comparative or dialogic modality was expressed in conceptual categories, recovered by the future teacher during the analysis of his practices. The analysis of the text showed the explicit use of educational theories to enrich his reflections, especially in relation to the levels of conceptualization (macroscopic and submicroscopic) and the discursive dimensions of Mortimer and Scott. These theoretical references were not only present in the classes' planning but were also integrated into his subsequent critical analysis, allowing a deeper reflection on his teaching practice.

On the other hand, this modality was also evident when the future teacher resorted to the levels of conceptualization to analyze how he presented the concepts about electrical circuits during his interactions with the group of students. For example, when he mentioned: "In the institution, we worked with the variables present in an electrical circuit [...] microscopically developing them, but, in addition, we worked in a macroscopic way by considering the variables related to the components present in an electrical circuit"). This passage from her analysis shows how she sought to integrate both levels to facilitate student learning. However, she also critically reflected on the difficulties this generated: "Perhaps my preconception was that I prioritized working at the submicroscopic level because I was not entirely satisfied with my practice in a previous school institution [...] but working with both levels simultaneously was what confused the students." This analysis, as a whole, shows a comparative and critical reflection: it evaluates how her pedagogical decisions impacted learning and proposes adjustments for future interventions.

On the other hand, she also used Mortimer and Scott's discursive dimensions to analyze her classroom interaction. In a specific episode, she describes how she used an interactive-authoritarian communicative approach to introduce new concepts: "My main intention in this fragment is to introduce and develop scientific history in the students [...] through a triadic pattern (I-R-E), where I ask questions, the students respond, and I proceed to evaluate them." This approach allowed him to structure the class so that students participated actively, although he acknowledges that this strategy limits the possibility of questioning the content presented.

The content of the text also showed the need to delve deeper into critical reflection by considering not only the immediate pedagogical decisions but also their broader ethical and social implications. This was reflected in fragments where the future teacher questioned how his methodological choices impacted student learning, recognizing the importance of adjusting his practices to avoid adverse effects in the future. For example, when reflecting on his decision to work simultaneously with the macroscopic and submicroscopic levels, he noted: "For this reason, I consider that perhaps my preconception was not wrong, but that working with both levels of conceptualization at the same time was what confused the students, and this was an incorrect decision that made the activity more complex." This fragment shows an effort to analyze how his decisions affected learning critically, but it focuses mainly on the immediate consequences within the classroom.

In addition, at another point, he expanded his critical analysis by considering broader dimensions and recognizing that structural and contextual limitations conditioned his planning. Specifically, she noted: "If I have the time to work through all three levels of conceptualization, this will be beneficial to student learning. However, I believe this was not beneficial from the detail of how it unfolded in the classroom." This attempts to link her practice to institutional and structural factors beyond her direct control, a step toward a new expression of critical reflection.

However, while she identified problems arising from the institutional context (such as lack of time), she did not fully explore these constraints' ethical or social implications. For example, she could have reflected on how these constraints systematically affect certain groups of students or how her practice could be adapted to mitigate educational inequalities. This type of analysis would be aligned with what Jay and Johnson13 describe as an expression of critical reflection, considering the broader ethical and sociopolitical implications of pedagogical decisions.

Another example of the emotional influence was evident when the future teacher described the technical problem with the simulator used in class: "When putting the simulator on a SmartTV, we noticed that the TV itself did not represent the HTML5 of the simulator well. For this reason, the application was not displayed correctly [...] This generated a feeling of frustration and demotivation in me at that moment." The content of this fragment shows how a critical incident related to technological resources not only affected the dynamics of the class but also had an emotional impact on the teacher, conditioning his perception of the development of the activity.

Another significant moment in his story occurred when he reflected on his inexperience with testers, a key tool for practical activities: "However, the main problem was not the use of the testers, but my inexperience in handling them. Even though I researched how they work and was handling them at home testing electrical circuits,... it was not enough to know how to measure the current correctly." Here, he acknowledged his insecurity and how this technical limitation affected both his performance and the measurements made by the students. This situation led him to improvise decisions to reorganize the activities and prioritize other objectives.

Furthermore, in his analysis, the future teacher showed how these emotions influenced his future teaching decisions. For example, after facing difficulties with the testers, he proposed a solution for future interventions: "However, next time, I would dedicate a special time to explain how the tester works and how to measure the variables correctly." This recognition of their emotions and impact on pedagogical decisions reflects an effort to redefine the experience and improve their teaching practice.

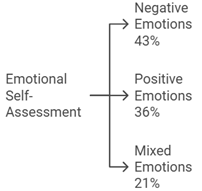

Complementing this last description, the emotions identified in the text were classified as positive, negative, and mixed or ambiguous (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Modalities associated with the "emotional self-assessment" category.

Source: Own elaboration.

First, among the negative emotions (43% of the total of the emotional self-assessment category; Figure 1l), frustration was one of the most recurrent and was associated with critical incidents related to technological resources ("When putting the simulator on a SmartTV, we noticed that the TV itself did not properly represent the HTML5 of the simulator. For this reason, the application was not displayed correctly [...] This generated a feeling of frustration and demotivation in me at that moment"). How an unexpected technical problem impacted not only the class's dynamics but also the teacher's emotional state, generating a feeling of demotivation that probably affected his disposition towards the rest of the activity. This frustration led him to improvise explanations about the figures observed in the simulator to continue the activity, which shows resilience in the face of adversity. However, it also highlights the importance of carefully planning when working with unknown technological resources. Another negative emotion identified was insecurity linked mainly to his technical inexperience with testers ("However, the main problem was not the use of the testers, but my inexperience handling them [...] Even though I researched how they worked and was handling them at home testing electrical circuits [...] it was not enough to know how to measure the current correctly"). This recognition revealed how his technical insecurity affected both his performance and the measurements made by the students. This feeling led him to reorganize the planned activities to prioritize more manageable tasks and avoid additional errors. In addition, he proposed dedicating specific time to future interventions to teach students how to use the testers correctly. This type of reflection shows an effort to redefine their experiences and improve their teaching practice.

On the other hand, among the positive emotions (36% of the total emotional self-assessment category; Figure 1), the satisfaction of observing specific achievements in student learning and successful teaching strategies stood out. For example, observing that an analogy used to explain submicroscopic concepts facilitated student understanding. Regarding an analogy used to explain submicroscopic concepts, he commented: "I think this analogy was useful for microscopically explaining electricity [...] This analogy was beneficial for working at the submicroscopic level because students could associate the phenomenon in question with electrons moving through ramps." This positive feeling reinforced his confidence in using analogies as a teaching tool and will probably motivate the teacher to continue using similar strategies in future classes. However, it could also have led the future teacher to underestimate these strategies' limitations for specific students or more abstract content.

Pride also appeared when he observed positive student activity results: "On the other hand, I consider that I managed to get the students to recognize the components and variables associated with an electric circuit." This feeling strengthened his positive perception of his teaching performance and reaffirmed his commitment to teaching.

Finally, mixed or ambiguous emotions (21% of the total emotional self-assessment category; Figure 1), such as challenge or tension between expectations and results, reflected internal tensions between his didactic preconceptions and the results observed during the intervention. For example, when reflecting on his decision to work simultaneously with macroscopic and submicroscopic levels, he commented: "I consider that perhaps my preconception was not wrong, but that working with both levels of conceptualization at the same time was what confused the students." This ambivalent feeling made him question his teaching knowledge and rethink his pedagogical strategies for future interventions.

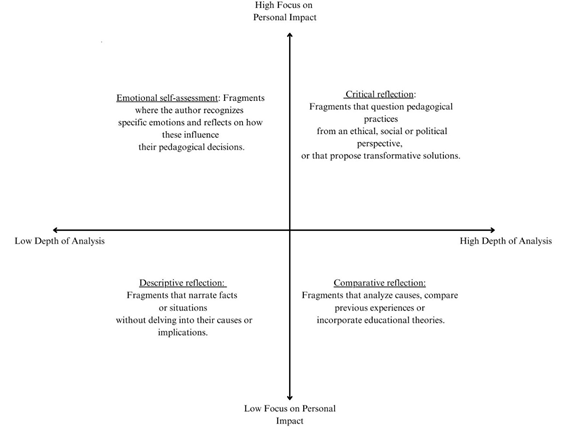

Figure 3 presents an image that proposes classifying the reflections in the four proposed categories (descriptive, comparative, critical, and emotional self-assessment) according to two continua: depth of analysis and focus on personal impact. This visual model is beneficial for interpreting the study's findings, as it allows contextualizing how the reflections written by the future teacher are distributed about these axes.

Figure 3 Classification of reflections according to analytical depth and personal impact.

Source: Own elaboration.

In the analysis, descriptive reflection (43% of the reflective units) was located in the lower left quadrant of the image, characterized by a low level of analytical depth and a low focus on personal impact. This type of reflection was limited to narrating facts or situations without delving into their causes or implications, consistent with previous studies that point out the predominance of this level in future teachers due to their inexperience. Comparative reflection (31% of the units of analysis) was positioned in the lower right quadrant, indicating a higher level of analytical depth but a low focus on personal impact. This level reflected efforts to analyze causes and connect experiences with educational theories, moving toward more complex forms of reflection. For example, when the future teacher evaluated his decision to work simultaneously with macroscopic and submicroscopic levels, identifying how this choice generated confusion among students.

Although less frequent (17%), critical reflection was located in the upper right quadrant, combining high analytical depth with a high focus on personal impact. This level was particularly valuable because it involved broader ethical and social questions about teaching practice and the proposal of transformative solutions. For example, the future teacher recognized the structural limitations of the time available to teach complex concepts and proposed methodological adjustments for future interventions.

Finally, emotional self-assessment, which represented 9% of the total, was located in the upper left quadrant, highlighting a high focus on personal impact but a low analytical depth. The emotions identified —such as frustration and insecurity— were closely linked to critical incidents related to technical problems or specific pedagogical decisions. These emotions not only influenced the teachers' immediate decisions but also their ability to redefine experiences and propose improvements.

Classifying reflections according to analytical depth and personal impact (Figure 3) organizes reflective categories within a clear visual framework and allows for analyzing how epistemic emotions interact with reflective levels. For example, negative emotions such as frustration were predominantly associated with descriptive reflections and emotional self-evaluations. In contrast, positive emotions such as pride were more frequently linked to comparative and critical reflections. This pattern reinforces previous research highlighting how emotions can act as catalysts for progressing toward more profound levels of reflection.32 This classification (Figure 3) organizes the preservice teacher's reflections based on their analytical depth and personal impact. It offers a practical conceptual framework for interpreting how epistemic emotions interact with reflective levels. Its value lies in its ability to synthesize complex data in an accessible way, facilitating the identification of patterns and trends that can inform both academic analysis and the design of training strategies. Furthermore, this tool is transferable to other educational contexts, making it a valuable resource for future research on teacher reflection and professional development.

This study aimed to analyze the reflections written by a future physics teacher on his teaching intervention in teaching electrical circuits to identify the levels of reflective depth, the associated emotions and the connections between theory and practice in order to understand how these dimensions impact his professional development and the improvement of his pedagogical practices. The results show how each objective dimension - identifying the levels of reflective depth, the associated emotions and the connections between theory and practice - was expressed in the analysis. Firstly, the levels of reflective depth were identified through a detailed analysis that allowed classifying the future teacher's reflections into four main categories: descriptive (43%), comparative (31%), critical (17%) and emotional self-assessment (9%). This finding confirms the trends observed in previous studies, such as those by Nian and Chudý,47 who highlight that future teachers tend to focus on descriptive and comparative levels during the initial stages of their professional development. However, progress towards critical reflections, although less frequent, evidenced a deeper questioning of the pedagogical decisions made, especially in the face of critical incidents related to technological resources or conceptual challenges.

Therefore, although the future teacher demonstrated progress towards critical reflection by questioning their own decisions and recognizing structural limitations, a deeper exploration of the ethical and social dimensions of the educational context is still lacking. This could be achieved through questions such as: How do these decisions affect students with different needs? What structural changes would be necessary to ensure more equitable teaching? Including this type of analysis would significantly enrich the reflective quality of the future teacher.

The connections between theory and practice were evident in explicitly integrating theoretical frameworks such as the macroscopic and submicroscopic levels to structure classes. Although this decision sought to enrich student learning, it also generated significant challenges related to the cognitive complexity involved. This finding reinforces what was pointed out by Taber26 and Johnstone et al.,48 who highlight the importance of carefully transitioning between different conceptual levels to facilitate learning. According to Caamaño,38 this integration can facilitate a deeper understanding of the physical phenomenon, but it also increases the cognitive load for students. In this case, the future teacher acknowledged that working simultaneously with both levels complicated learning: "Perhaps my preconception was that I prioritized working at the submicroscopic level because I was not completely satisfied with my previous practice [...] but working with both levels simultaneously was what confused the students." The difficulties observed could be explained by methodological limitations, such as the condensed planning of the classes, the lack of technical preparation to handle resources such as simulators and testers, and especially the lack of sufficient time to develop each conceptual level adequately. This finding coincides with Taber,27 who emphasizes that transitioning between different conceptual levels requires careful didactic design to avoid confusion. These results directly respond to the stated objective and highlight how these dimensions impacted the professional development of future teachers by encouraging more reflective and informed practice.

On the other hand, using analogies as a teaching tool was identified as an effective strategy but not without limitations. The analogy based on ramps and marbles allowed students to visualize submicroscopic phenomena. However, some had difficulties correctly associating the analogy with scientific concepts: "Some students did not fully understand the idea and took the example very literally." This result coincides with the warnings of Parma et al.,49 who highlight that analogies must be carefully selected and explained to maximize their effectiveness. According to Mammino,50 analogies help understand abstract concepts as long as they are used within a clear discursive framework to avoid misunderstandings.

Emotions played a central role in the reflective process of the preservice teachers. Negative emotions, such as frustration and insecurity, were linked to critical incidents related to technical problems (simulator) or personal limitations (handling testers). These emotions directly influenced their teaching decisions, such as reorganizing activities or improvising explanations ("This generated a feeling of frustration and demotivation in me at that moment"). For Pekrun et al.,2 these emotions can temporarily limit teachers' reflective capacity and act as catalysts for future changes if managed appropriately. These findings are consistent with recent research on epistemic emotions in initial teacher training,1,2 which underlines how emotions influence immediate decisions and long-term professional development.

Some of the teaching practice's results were unexpected or contradictory. For example, although the future teacher sought to integrate conceptual levels to enrich learning, this decision confused some students due to the cognitive complexity involved. This finding could be explained by methodological limitations related to the condensed planning of the lessons or by contextual factors such as the limited time available for the intervention. In addition, although valuable critical reflections were identified, these were less frequent than expected, suggesting that the teacher's reflective development is still in process. Compared to previous studies, this work reinforces the relevance of epistemic emotions in science teaching, as proposed by Hernández del Barco et al..1 These emotions associated with knowledge construction are particularly relevant in educational contexts where teachers face uncertainty or complex conceptual challenges. The future teacher showed an incipient ability to identify and manage his emotions, which is consistent with the findings of Fried et al. (2015), who highlight that emotional recognition is a crucial step towards deeper reflection.

These results have significant practical implications for initial teacher training. First, they highlight the need to include training strategies that encourage more profound and critical reflection among future teachers. This could be achieved through the use of structured guides to analyze critical incidents or guided discussions on ethical and pedagogical dilemmas. Furthermore, it is essential to provide opportunities for teacher trainees to develop technical skills related to using complex teaching resources, such as simulators and testers. Furthermore, the findings underline the importance of balancing the didactic use of conceptual levels in science teaching. Although working simultaneously with macroscopic and submicroscopic levels can enrich learning, it is essential to adapt these pedagogical decisions to the specific context and needs of the student group.51 This involves considering factors such as available time, technological resources, and students' prior level of knowledge.

Although the study was based on a single case, its findings offer a valuable interpretive framework for understanding how future teachers process their experiences and develop reflective skills. This qualitative approach is not intended to make universal claims but to provide a rich basis for future research exploring similar phenomena in other educational contexts. The detailed analysis of a preservice physics teacher's reflections allowed us to identify significant patterns in his reflective and emotional practice, which may resonate with the experiences of other preservice teachers. For example, the epistemic emotions identified in this study - such as frustration linked to technical problems and pride associated with pedagogical achievements - are experiences other preservice teachers will likely share when facing similar challenges. According to Hsieh and Shannon (2005), this type of detailed analysis allows for the construction of emerging theories that can be explored and adapted in different educational contexts.

Based on the findings obtained, several lines of research emerge that could enrich knowledge about teacher reflection and its relationship with emotions and conceptual levels in science teaching. First, it would be valuable to explore how different pedagogical approaches can facilitate or hinder the transition between macroscopic and submicroscopic levels in diverse educational contexts.54 Furthermore, future research could focus on evaluating specific interventions designed to strengthen reflective and emotional skills in preservice teachers, such as critical incident-based workshops or structured guides for reflection.1 It would also be interesting to analyze how epistemic emotions influence long-term teacher professional development and how these emotions can be managed to promote more effective pedagogical practice.2

Finally, this work extends the existing conceptual framework by explicitly integrating an emotional dimension into teacher reflective analysis. This response to recent calls in the literature on preservice teacher education to consider emotions as a secondary aspect of the reflective process and as a central component that influences immediate decisions and long-term professional development.2

The present study analyzed the written reflections of a preservice physics teacher on his teaching intervention in electrical circuits. The aim was to identify the levels of reflective depth, the associated emotions, and the connections between theory and practice. The results allow us to understand how these dimensions impacted his immediate teaching decisions and long-term professional development. This study contributes to the field of initial teacher education by providing empirical evidence on how epistemic emotions and reflective writing influence the professional development of preservice teachers. The findings highlight the importance of considering cognitive and emotional aspects in the reflective process, overcoming purely technical or instrumental approaches.

The practical implications for preservice teacher education are significant. First, the need to design training strategies that encourage more profound and critical reflection is highlighted, explicitly considering the role of emotions in the reflective process. This could be achieved through structured guides to analyze critical incidents or guided discussions on ethical and pedagogical dilemmas. The findings underscore the importance of balancing conceptual levels in science teaching. While working simultaneously with macroscopic and submicroscopic levels can enrich learning, it is critical to adapt these pedagogical decisions to the specific context and needs of the student group.

From a qualitative perspective, the present study offers valuable insights into the epistemic emotions and reflexive levels faced by preservice teachers. Adopting a naturalistic perspective highlights the importance of analyzing individual experiences as a basis for building broader interpretive frameworks that can enrich teaching practice and professional development. According to Lincoln and Guba,37 this type of generalization allows findings to be transferable to similar contexts as long as readers carefully assess the similarities between the case studied and their realities. Finally, this work opens new lines of research that deserve to be explored, such as the impact of specific interventions to strengthen reflective and emotional skills in future teachers and the longitudinal analysis of how epistemic emotions influence teachers' professional development over time.

None.

None.

©2025 Cutrera. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.