Research Article Volume 2 Issue 4

Frequency dependent site response inferred from microtremors accompanied by ambient noise

Biswas R,1

Regret for the inconvenience: we are taking measures to prevent fraudulent form submissions by extractors and page crawlers. Please type the correct Captcha word to see email ID.

Bora N,1 Baruah S2

1Department of Physics, Tezpur University, India

2CSIR?NEIST, Geoscience Division, India

Correspondence: Rajib Biswas, Department of Physics, Tezpur University, Assam?784028, India, Tel 9199-54-31-3970

Received: April 25, 2018 | Published: July 5, 2018

Citation: Biswas R, Bora N, Baruah S. Frequency dependent site response inferred from microtremors accompanied by ambient noise. Phys Astron Int J. 2018;2(4):273-277. DOI: 10.15406/paij.2018.02.00098

Download PDF

Abstract

We report frequency dependent estimation of site response. Towards this objective, we deploy widely established receiver function technique. Taking locally recorded events as inputs, we implement this technique to estimate resonance frequency in three receiver sites, characterized by varying lithology underneath. It is observed that resonance frequencies varies from 3 to 7 Hz, which is also confirmed by our previous studies of estimates from ambient noise recordings with reference to identical sites. Variation of frequency implies existence of heterogeneity in the study area.

Keywords: site response, resonance, receiver function

Introduction

Estimation of spatial variation of site response is one of the prime objectives of microzonation studies. Several literatures outlined the paramount significance of site dependent factor which largely impact the extent of damage in certain pocket areas pertaining to local geology.1–7 Even the shaking of man–made structures also gets affected by the spatial variation of site effects. The site effects can be parameterized by factors like resonance frequency, amplification factor which have direct impact on semi–resonance or resonance of certain building types, and thereby causing distortions or failures of constructions. In order to compute site response, there are adoptions of various methodologies.8–11 HVSR or receiver function technique has been widely regarded as one of the most powerful methods available to seismologist for acquiring a reliable estimate of site response.

In this work, we endeavor to estimate site response through horizontal to vertical ratio of microtremors. We give a comprehensive analysis of the results attained through horizontal to vertical ratio of locally recorded waveforms.

Data

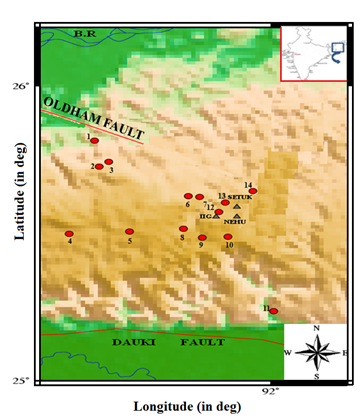

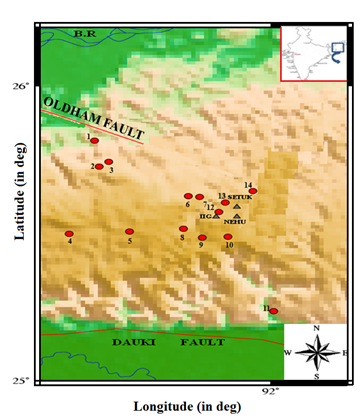

In order to generate local waveforms exclusively for this study, a temporary network of three stations namely IIG, NEHU and SETUK were installed in Shillong City, India. This network was operational for two months. The stations were equipped with three Trillium 120P sensors from Nanometrics having frequency bandwidth of 0.003 to 50 Hz; with 24 bit Guralp Digitizer in synchronization with Guralp GPS. It was a continuous mode of recording in all the three stations. The data were digitized at a sampling frequency of 100 samples /second. The stations are shown in Figure 1. A total of 135 tremors were recorded during the period of deployment of this temporary network. Out of this, a total of 40 tremors recorded by the three stations were precisely located adopting the velocity model of Bhattacharya et al.,12 compatible for Shillong region with a view to determine the hypocentral parameters. Out of these 40 events, only fourteen events have been selected in order to study the site response from HVSR in this study region within an epicentral distance of less than 50 km. Table 1 provides the hypo–central parameters of the located events. The depths of the events vary from 4 to 25 km whereas the epicentral distance ranges from a mere 1.9 km to 48 km. The root mean square of the located events is below 0.2.

Date

Yy mm dd |

Origin time

hh mm ss |

Latitude

in deg |

Longitude

in deg |

Depth

km |

Mag |

09 03 09 |

18 37 49.45 |

25.744 |

91.579 |

32.87 |

2.26 |

09 03 09 |

18 37 49.45 |

25.728 |

91.554 |

30.24 |

2.6 |

09 03 19 |

17 45 12.73 |

25.237 |

92.008 |

35.04 |

2.48 |

09 03 20 |

21 03 32.47 |

25.574 |

91.865 |

20 |

1.85 |

09 03 22 |

19 28 57.65 |

25.645 |

91.954 |

9.53 |

1.62 |

09 03 27 |

35 02 35.41 |

25.625 |

91.815 |

4.09 |

1.64 |

09 03 28 |

09 05 06.80 |

25.5 |

91.476 |

21.67 |

2.51 |

09 03 29 |

17 03 08.63 |

25.508 |

91.633 |

20.8 |

2.39 |

09 03 30 |

02 31 38.27 |

25.49 |

91.889 |

18.6 |

2.17 |

09 03 30 |

07 31 28.26 |

25.628 |

91.786 |

21 |

1.44 |

09 03 30 |

19 55 05.92 |

25.606 |

91.882 |

13.3 |

1.55 |

09 03 31 |

10 15 38.23 |

25.487 |

91.822 |

19.55 |

2.05 |

09 03 31 |

21 26 16.86 |

25.517 |

91.773 |

20.8 |

1.87 |

Table 1 List of the events.

HVSR estimation

As per reports of Aki et al.,2 & Kawase et al.,3 microearthquake study entailing events at short epicentral distances facilitates the understanding of physics of source processes as well as local site conditions. HVSR is based on the assumption that vertical component is least affected by near–surface influence. Consequently, when we divide the horizontal component by vertical component, the site effect can be deciphered.

Theoretical background

As an input for HVSR, we incorporate S–wave packets. Suppose,

and

represent S–wave amplitude and the background noise amplitude, respectively with a hypo central distance of

. The relation between signal amplitude

with respect to frequency

emerges to be,

(1)

Assuming k events being recorded by j stations, the amplitude spectrum

in frequency domain of

can be expressed as6,13,14

(2)

The corresponding HVSR can be estimated as

(3)

where

,

and

represent the Fourier spectra of the North–South component, East–West and Vertical component, respectively. By taking into account the contribution of all the seismic events, the average receiver function

is estimated.

Approach

HVSR yields a peak with existence of an impedance contrast. The epicentral plot of the events used for implementing this receiver function is illustrated in Figure 1. The horizontal to vertical ratio technique adopted for the locally recorded earthquakes in the present study is described below:

Figure 1 Epicentral plot of the locally recorded events denoted by filled circles. The receiver sites are represented by the filled triangles. BR stands for Brahmaputra River. The study area is shown in the inset.

- Differentiation of the S–wave motions from multiple station

- Instrument response correction with incorporation of poles and zeroes

- Adoption of band pass filter in the range of 0.1–10 Hz.

- The S–wave packets recorded are analyzed with a window length containing the maximum amplitude following king et al.1 The resultant multicolumn files containing the corrected displacement spectra are fed as input in the custom made Matlab code.

- During estimation HVSR, we ensure that the corrected spectra possess SNR>3 to eliminate all sorts of plausible transients.1

Results

The receiver function was determined at the three temporary stations viz, SETUK, NEHU and IIG incorporating the waveforms recorded by this temporary network. All these stations are characterized by different type of site geology. The HVSR yields different type of amplification levels and peak frequency corresponding to highest amplification. All these are elaborate station wise.

Station: IIG

The average HVSR result for IIG station including all the local events utilized are outlined between 4 and 6.8 Hz, as evident from Figure 2A. In between 3 and 5 Hz, an appreciable level of amplification is found which later on decays. But, with increment of frequency the amplification rises again and reaches the peak at 1.285. The frequency corresponding to the highest amplification, generally referred to as the fundamental frequency, is hence found to be 6.4 Hz. Meanwhile, the level of amplification remains above one, although very low, for this entire range of frequency. It is worthwhile to note that for higher side of frequencies, no amplification is observed.

Station: SETUK

Similarly, the average HVSR for SETUK station is also estimated which is shown by Figure 2B. The range of frequency outlining the amplification levels is observed to be from 5 to 9 Hz. Interestingly, SETUK reveals a different pattern of site response. Drastic decline of site amplification is contemplated once the peak frequency entailing the highest site response is crossed. SETUK station is characterized by peak frequency of 8Hz. Towards higher side of frequencies above 9 Hz, site amplification is quite negligible. The site response hardly goes beyond 1.0 except at the peak frequency within the frequency band observed in this case. Site amplification is found to be in the range of 0.8 to 1.0 only.

Station: NEHU

Likewise, the average receiver function is also evaluated for NEHU station exploiting the local waveforms recorded during its deployment exclusively for this study. Here also, the average HVSR shows appreciable site response in the same band of frequencies as has been observed for SETUK, i.e; 5 to 9 Hz, as illustrated in Figure 2C. Point of dissimilarity in these two stations arises with the inferred peak frequencies. The average HVSR reveals a fundamental or so called peak frequency at 7.4 Hz. However, the site amplification exhibited by this station is quite higher in comparison to the other two sites. Mostly, the site response is coming within the range of 0.95 to 1.6 which is not usually the case seen for the other two sites. More importantly, the range of frequencies within which the site amplification attains its highest level comes out to be the same for station SETUK and NEHU. It is indicative of the fact that both these sites might be characterized by existence of basement rock strata at the same level of depth.

Discussions

In this study, emphasis was given to estimate site response from computation of HVSR. The earthquakes utilized in this study indicate the level of seismic hazard in Shillong City for damage and destruction. Shillong has experienced no. of felt earthquakes in the recent past and has seen huge urbanization during last two decades. This has called an extensive study with the incorporation of various ground parameters like geology, topography, subsoil condition, geomorphology, seismicity, site amplification behavior and the attenuation parameter. Extensive work throughout the world has been carried out by different researchers so as to discern the spatial variability of seismic responses with HVSR formulation–receiver function technique.13,15 It is noteworthy to mention that all of their findings strongly put HVSR as the effective approach while estimating the site response in context of fundamental frequency of receiver site. As depicted in Figure 2, we can observe different type of amplification levels and peak frequencies as yielded by the average HVSR results. This implies frequency dependence of site response with three stations in consideration. While we find lower magnitude of amplification in high frequency range, the opposite trend prevails in low frequency range. It is found that resonance frequency is mostly prominent in the range of 4–8 Hz when all the three receiver sites are taken into account. The IIG site reached its peak at 5.5 Hz as while the rest two sites attained the highest amplification levels attain maximum corresponding to frequencies of 6–7 Hz for two sites. This observation is found to be in good conformity with the estimates of fundamental frequencies estimated through ambient noise recordings at these same sites as reported in Biswas & Baruah,16 Biswas et al.,17 Biswas & Baruah.18,19 As documented in these reports, the horizontal to vertical ratio by modified technique of Nakamura et al.,20,21 showed identical estimates of fundamental frequencies for these sites. The resonance frequency estimates at these three sites from ambient noise recordings reveal same pattern. In all cases, the estimates emerged to be ~4 to 8 Hz. Likewise, Biswas et al.,17,18 reported resonance estimation through reference site technique. As per their report, the amplification was found to be dominant in the frequency range of 3 to 7 Hz. Thus, it can be inferred that receiver function technique effectively reveals the fundamental frequencies at the sites under investigation. The estimations also implicate that there are spatial variation in geology and soil conditions prevailing in the region.22

Conclusion

The site response has been estimated from locally recorded events with adoption of receiver function technique. The fundamental frequencies are found to be in the range of 3 to 7 Hz for the study area pertaining to three receiver sites. The variation in resonance frequencies as computed from this technique implicates prevalence of heterogeneity in the study area. We find good corroboration between estimates of fundamental frequencies from receiver function technique with reference to local events and as that of ambient noise records for the study area. The study will help in future course of mitigation studies in this region.

Acknowledgements

Conflict of interest

Author declares there is no conflict of interest.

References

- King JL, Tucker BE. Observed variations of earthquake motion across a sediment–filled valley. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 1984;74(1):153–165.

- Aki K. Local site effects on ground motion, Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics II–Recent Advances in Ground Motion Evaluation. USA: Proceedings of the ASC, Speciality Conference; 1988. p. 103–155.

- Kawase H. The cause of the damage belt in Kobe: the basin–edge effect, constructive interference of the direct S–wave with the basin induced diffracted/Rayleigh waves. Seismological Research Letters. 1996;67(5):25–34.

- Field E, Jacob K. The theoretical response of sedimentary layers to ambient seismic noise. Geophysical Research Letters. 1993;20(24):2925–2928.

- Nath SK, Sengupta P, Sengupta S, et al. Site response estimation using strong motion network: A step towards microzonation of Sikkim Himalayas; Seismology 2000. Current Science. 2000;79:1316–1326.

- Nath SK, Biswas NN, Dravinski M, et al. Determination of S–wave site response in Anchor–age, Alaska in the 1–9 Hz frequency band. Pure and Applied Geophysics. 2002;159(11–12):2673–2698.

- Nath SK, Sengupta P, Kayal JR. Determination of site response at Garhwal Himalaya from the aftershock sequence of 1999 Chamoli earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 2002;92(3):1071–1081.

- Castro RR, Anderson JG, Singh SK. Site response, attenuation and source spectra of S–waves along the Guerrero, Mexico, subduction zone. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 1990;80(6A):1481–1503.

- Field EH, Jacob K. A comparison and test of various site response estimation techniques, including three that are non reference–site dependent. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.1995;85(4):1127–1143.

- Bonilla LF, Steidl JH, Lindley GT, et al. Site amplification in the San Ferdinando Valley, California: variability of site effect estimation using S–wave, coda, and H/V methods. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.1997;87(3):710–730.

- Riepl J, Bard PY, Hatzfeld D, et al. Detailed evaluation of site response estimation methods across and the sedimentary valley of Volvi (EURO–SEISTEST). Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 1998;88(2):488–502.

- Bhattacharya PM, Pujol J, Mazumdar RK, et al. Relocation of earthquakes in the Northeast India region using joint Hypocenter determination method. Current Science. 2005;89(8):1404–1413.

- Lermo J, Chavez–Garcia FJ. Site effects evaluation using spectral ratios with only one station. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 1993;83(5):1574–1594.

- Mandal P, Chadha RK, Satyamurty C, et al. Estimation of Site Response in Kachchh, Gujarat, India, Region Using H/V Spectral Ratios of Aftershocks of the 2001 Mw 7.7 Bhuj Earthquake. Pure and Applied Geophysics. 2005;162(12):2479–2504.

- Langston CA. The effect of planar dipping structure on source and receiver responses for constant ray parameter. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.1977;67(4):1029–1050.

- Biswas R, Baruah S. Site response estimation through Nakamura Method. India: Geological Society of India; 2011.

- Biswas R, Baruah S, Bora. Mapping sediment thickness in Shillong City of northeast India, through empirical relationship. Journal of Earthquakes. 2015.

- Biswas R, Baruah S. Non–Linear Earthquake Site Response Analysis: a Case Study in Shillong City. International Journal of Earthquake Engineering and Hazard Mitigation. 2015;3(4).

- Biswas R, Baruah S. Shear Wave Velocity Estimates through Combined Use of Passive Techniques in a Tectonically Active Area. Acta Geophysica. 2016;64(6):2051–2076.

- Nakamura Y. A method for dynamic characteristics estimation of subsurface using microtremor on the ground surface. Quarterly Report of RTRI (Railway Technical Research Institute). 1989;30(1):25–30.

- Nakamura Y. On the H/V Spectrum. China: 14th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering; 2008.

- Mundepi AK, Mahajan AK. Soft soil mapping using horizontal to vertical ratio (HVSR) for Seismic Hazard Assessment of Chandigarh City in Himalayan Foothills, North India. Journal of the Geological Society of India. 2010;75:799–806.

©2018 Biswas, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the,

which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.