eISSN: 2572-8474

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 5

1Department of Nursing, Sanitas University Foundation, Colombia

2Department of Nursing, National University of Colombia, Colombia

Correspondence: Diana Marcela Martínez Vallejos, Nursing School, Sanitas University Foundation, Colombia

Received: October 16, 2019 | Published: October 25, 2019

Citation: Vallejos DMM, Molina LMH. Valuation of nursing care in the preparation course for maternity and paternity. Nurse Care Open Acces J. 2019;6(5):175-178. DOI: 10.15406/ncoaj.2019.06.00204

Maternal health is included in the sustainable development objective 3: "health and wellness" charted in the UN conference in Rio de Janeiro in 2012.1,2 In Colombia prenatal care is regulated by Resolution 412 of 2000, in the Clinical Practice Guidelines "detection of alterations in pregnancy", updated in 2013 by the Ministry of Health and Social Protection of Colombia.3–5

Given the high birth rates in the country in the younger population, it is clear that there is no education in the family, in the community, and there is easy access to educational programs in schools and health institutions, by various cultural factors such as taboo on sexuality, family planning methods and gestation.6,7

For the conditions described previously in 2016 the Ministry of Health and Welfare announced the policy of comprehensive health care (PAIS), a law that gives rise to the Integral Model of Health Care (MIAS), which aims to generate comprehensiveness in health care and well-being of Colombians, for which coordination is required between all stakeholders in the health sector in order to carry out actions to regulate the determinants and risks that influence health and well-being population.8

For the implementation of this new model the Comprehensive Routes Health Care (RIAS), one of these is the comprehensive route health care 8 for perinatal maternal population were designed, in which actions are proposed to improve health conditions of the pregnant woman and her unborn child.8

On professional experience and literature has been observed that some pregnant women do not have adequate adherence to prenatal care programs, especially the preparation for parenthood, here are some factors that could explain this phenomenon are named :

The process of gestation is a period of change for parents who are awaiting the new being; therefore becomes important care provided by health professionals especially nurses in order to propender for the welfare of the mother and the unborn child through the care given to this dyad and activities education that are provided during the prenatal period to prevent disturbances during pregnancy, childbirth, newborn care and to promote healthy habits during the prenatal and postpartum period.10–16

That is why the need to know and describe how valued the care provided by the nurse to pregnant women attending the preparation of motherhood and fatherhood in a private IPS in Bogotá through the application arises scale professional care scale derived from professional care (CPS) of Dr. Kristen Swanson Spanish version, 2011.17

This study is descriptive quantitative approach, prospective took place in a private IPS in Bogotá during the second half of 2017. A sample of 331 pregnant women with a margin of error of 5% and confidence interval was calculated 95%, simple random probability sampling was performed were included in older pregnant 15-year study literate, between the second and third quarter had attended at least 2 of the 4 sessions of affiliates during the EPS linked to the IPS who applied the rating scale derived from professional care professional care scale (CPS) Dr. Kristen Swanson Spanish version, 2011.17

Researchers are girded with international ethical recommendations of CIOMS (Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences), Resolution 008430 of 1993, Law 911 of 2004, the code of childhood and adolescence and ethical principles: truthfulness, fidelity, mutuality , beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy and justice 18 which was approved by the ethics committees of the Faculty of nursing National University of Colombia and the IPS Virrey Solis.

This instrument has two dimensions: healing competent and compassionate healer is valid global content of 0.893 and 0.907 Cronbach's alpha.17 The application of the scale was done in units of basic care institution providing health services in the sessions of preparation for parenthood, explanation and purpose of the study each gestante was made, it was verified its understanding, he surrendered in physical informed consent, which was completed by users and then I filled each format with the instrument.

The results of this research were analyzed taking into account the scores obtained after the application of the instrument scale professional care derived from the Caring Professional Scale (CPS) of Dr. Kristen Swanson, Spanish version 2011.17

Tabulation was performed on a spreadsheet Excel data obtained were then exported to SPSS version 24 and then analyzing the results and variables in order to test the hypothesis in this research was conducted.

Participants were between 15 and 43 years old, average age was 25.8 years. Most pregnant women were between 21 and 27 years old, one can see that the number of pregnant women with extreme age was low, 7 pregnant were less than or equal to 16 years old and 30 greater than or equal to 35.

As for the educational level: 3% had primary education, 42.9% had completed high school, 30.8% had completed a technical degree, 21.5% were professionals, while 1.8% had graduate, according to these statistics although the vast majority of pregnant women had a high school education and a large number of them had advanced levels of technical / university higher education if it could be inferred that pregnancy influences the opportunity to continue academic training as it has a major social impact because of the difficulty in simultaneously play the role of mother and child.

Referring to marital status variable 1.5% of pregnant women reported being separated, married 9.3%, 39.2% 49.8% while single living in union; While this may reflect an aspect that has much to do with religion and culture, could also be associated with educational level, occupation and socioeconomic status, according to data being presented could be concluded that pregnant women living in free union or who are single are among the lowest socioeconomic levels.

Faced with gynecological and obstetric history is important to note that most women who participated in this study were not planning a pregnancy or wanted at this point in their lives, yet all accept stated gestation. It may show that 75.2% of pregnant women did not plan their pregnancy, on the other hand 24.7% if they had planned.

As for the current pregnancy was evident maternal risk classification where 42.3% of pregnant women were classified as high risk while 57.7% low risk, according to the extreme age as maternal risk factor, it was shown that 83.3% of pregnant añosas and 71.4% of very young pregnant were taking a high-risk pregnancy; it is worth noting that took into account the risk classification were pregnant at the time of the instrument, since this information is subject to complications that can occur during pregnancy and may vary.

Participants were between weeks 14 and 39 of gestation with an average gestational age of 26.6; where the highest concentration of pregnant women was in week 23, 24, 25 and 26. 58.3% of the participants were in the second quarter as 41.6% in the third trimester (Table 1).

Item |

Never |

sometimes yes, sometimes no |

most times |

Siempre |

Compassionate healer |

||||

Made her feel good? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Showed a positive attitude with you and your pregnancy? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

I listen carefully to you? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Are you allowed him to express his feelings? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Are you showed interest in what happens to you? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Have you understood your symptoms and concerns? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Did showed that he was prepared to do their job? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

competent healer |

||||

Is encouraged her to continue caring for your pregnancy? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Was respectful to you? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

How will I provide help and collaboration? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

I realize correctly the course of preparation for parenthood? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

What felt cared for during the course of preparation for parenthood? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Do I explain clearly the signs to follow? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Was it nice to you? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Is he treated as a person? |

one |

2 |

3 |

4 |

57.7% of pregnant women gave the highest score in the dimension of compassionate healer while 74.3% gave the highest score in the dimension of competent healer. This fact makes evident that the skills of nursing professionals are notorious for the human component pregnant.

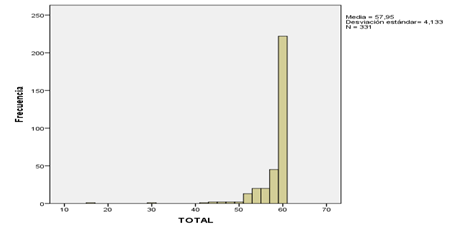

0.3% of participants rated the care provided by nurses in the course of preparation for parenthood as deficient, as a regular 0.3%, 3.6% and 95.7% as good of pregnant women felt that the care provided by nurses in the course was excellent. Figure1 94.2% of pregnant women with low risk pregnancies assessed care provided nursing preparation for parenthood as excellent figures 3.6 percentage points lower than those reported in participants who were enrolled with gestations high-risk.

Figure 1 Total frequency scale.

Source: Data obtained by the researcher in this study: "Assessment of nursing care in the course of preparation for parenthood".

100% of pregnant women in extreme age and 95.2% of pregnant women between 17 and 34 evaluated the care provided by the nurse in the course as excellent.

94.8% of pregnant women who were in the second trimester and 97.1% who were enrolled in their third trimester of pregnancy assessed as excellent the care received by nurses in the course of preparation for parenthood and paternity.

The data described allow us to see that there is a noticeable difference in the scores on the scale of professional care when comparing pregnant by chronological age, gestational age or risk classification.

The findings on the social characteristics in this research agree in some respects with the perception study of nursing care in antenatal care Guzman, even if it comes from different regions of Colombia, as both it is reported that most pregnant cohabiting and have the secondary level.19

However differences in the ranges of chronological age where ages are reported from 18 to 35 in the study of Guzman found, whereas in the present investigation ages of pregnant women showed greater variability being between 15 and 43 years old.19

Regarding gynecological and obstetric history are also similarities between the two studies where more than half of the participants were primiparas.19

According to the score obtained in the two dimensions of the scale there are similarities compared to findings presented by Ortega in his studio, where the lowest score in the intervention group in the healing dimension competent was in item 11 he performed correctly control your pregnancy? (The preparation for parenthood for this study).20

In the dimension of the compassionate healer it demonstrated that the items with the lowest score in the same group were does he feel good? And it allowed him to express his feelings? while in the control group were allowed to have you express your feelings? And demonstrated interest in their symptoms and concerns?; in this investigation are presented some similarities with the study by Ortega opposite the score of the control group and intervention in item 4, while the control group with item 5.20 Although the population of both studies was different care settings valuation by pregnant women has similarities.20

As for the results obtained in this research, according to their score in the scale professional care derived from the Caring Professional Scale (CPS) of Dr. Kristen Swanson Spanish version, 2011,17 shows that the assessment of care offered by nurses to pregnant women who perform the preparation for parenthood excellent coincides with the findings in the study of Suarez and Bejarano, since in the latter after the interviews the researchers showed that pregnant perceived nursing care as a holistic which led them to conclude the preparation for parenthood it can be located in the vision of transformative nursing unitaria.21

Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel – Capes.

None.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2019 Vallejos, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.