eISSN: 2572-8474

Research Article Volume 3 Issue 3

Faculty of Human Science, Department of Nursing, Sophia University, Japan

Correspondence: Katsuhiro Hiratsuka, Faculty of Human Science, Department of Nursing, Sophia University, Japan and Graduate School of Nursing, Chiba University, Japan, Tel +81 3 3950 6903

Received: June 27, 2017 | Published: July 14, 2017

Citation: Hiratsuka K. Daily life of adolescents with biliary atresia surviving with their native liver: change process of the patient-parent relationship. Nurse Care Open Acces J. 2017;3(3):266-268. DOI: 10.15406/ncoaj.2017.03.00074

Purpose: To describes the characteristics of the daily lives of adolescents with biliary atresia surviving with their native liver, and those of their parents, as well as the patient-parent relationship.

Method: The participants were adolescents with biliary atresia surviving with their native liver, and their parents. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews individually with patients and parents. And qualitative content analysis was used.

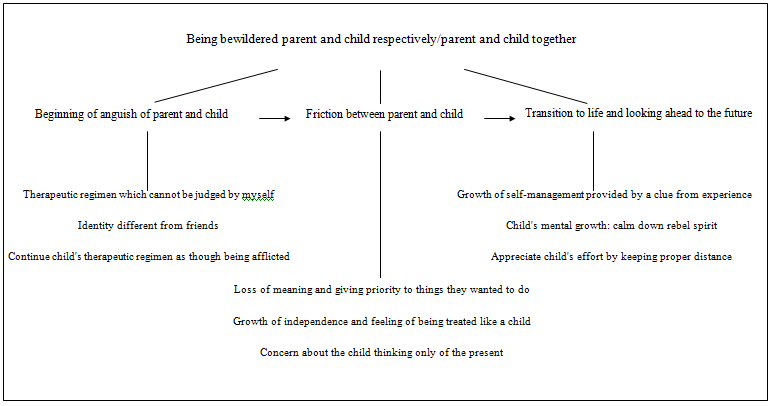

Result: The theme of the daily lives of the patients and their parents during the adolescent period involved a change process and be bewildered from “parent and child respectively” to “parent and child together.” This theme was composed of three categories; Beginning of anguish of parent and child, Friction between parent and child, and Transition to life and looking ahead to the future.

Conclusion: The patients with biliary atresia surviving with their native liver, and their parents, were bewildered because of the ambiguous nature of biliary atresia, the possibility of LDLT, and characteristics of the adolescent developmental stage. Nurses should become the compensating factor to reconstruct patient-parent relationships and support patients in acquiring understanding of their illness and experiencing suitable developmental stages in school or society.

The state of awaiting liver transplantation causes cognitive uncertainty for a patient.1 Most children undergoing liver transplantation are those with biliary atresia, and most liver transplants to a child are carried out by a donation from their parents in Japan.2,3 The ambiguous nature of biliary atresia and the possibility of living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) cause suffering to not only patients but also parents who are candidate donors.4 In addition, when patients reach adolescence, the relationship between children and parents changes, which might make their suffering more complicated. Therefore, this study examines whether adolescent patients and their parents experience suffering in their daily lives, how this shifts during the adolescent period, and how this suffering relates to the nature of biliary atresia and the future possibility of LDLT. Specifically, this short report describes the characteristics of the daily lives of adolescents with biliary atresia surviving with their native liver, and those of their parents, as well as the patient-parent relationship.

The participants were adolescents with biliary atresia surviving with their native liver, and their parents. This survey was conducted in a single outpatient center of a national university hospital in an urban area of Japan, from November 2016 to February 2017. The inclusion criteria were

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews individually with patients and parents. The focus of the interview was the experience of the adolescent period with biliary atresia and possible need for LDLT in the future, and the relationship between children (i.e., patients) and parents. Each interview was transcribed verbatim and qualitative content analysis5,6 was used. The specific procedure for analysis was as follows: Contents of the characteristics of their daily lives were extracted from the transcription, the extracted components were coded into concise sentences in each case, and each code was classified into categories according to the similarity of contents across all cases. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Graduate School of Nursing of Chiba University, Japan (Approval No.28-58).

Characteristics of participants

Three pairs of patients and their parents participated Table 1. There were various complications in each of these cases. Only one case had been diagnosed by a physician as needing to receive LDLT and had prepared for LDLT. The mother accompanying the patient was not a candidate donor.

Age/Gender of Patient |

Age/Gender of Parent |

Complications |

LDLT Status |

21/Female |

40s/Mother |

Cholangitis(repeatability) |

Not necessary now |

24/Female |

40s/Mother |

Cholangitis(repeatability) |

Preparing now |

25/Male |

50s/Mother |

Hepatatrophia (mild case) |

Not necessary now |

Table 1 Characteristics of adolescents with biliary atresia surviving with their native liver and their parents.

Status of daily life among adolescents and their parents

Being bewildered parent and child respectively/parent and child together: The theme of the daily lives of the patients and their parents during the adolescent period involved a change process and be bewildered from “parent and child respectively” to “parent and child together” Figure 1. They were bewildered respectively during the early adolescent period by a gap existed in recognition and attitudes toward the illness between the patients and parents. Thereafter, they could reconstruct their relationship by patient’s growth. However, there were still several problems related to the nature of biliary atresia and LDLT, and they were bewildered together during the late adolescent period.

Beginning of anguish of parent and child: Not only patients who had experienced cholangitis repeatedly, but also patients who were without complications experienced “Therapeutic regimen which cannot be judged by myself” when they were approximately junior high school students. In addition, these patients experienced that they were different (“Identity different from friends”) because of changes in their appearance (e.g., operation scars or abdominal dropsy) and activity limitations. Parents recognized that causation between therapeutic regimen and their children’s condition were ambiguous, and tended to choose to “Continue child's therapeutic regimen as though being afflicted.” At this time, conflict between patients and parents was not actualized; however, a gap existed in recognition and attitudes toward the illness between the patients and parents.

Friction between parent and child: Patients began to recognize that causation between therapeutic regimen and their condition were ambiguous, which might have caused “Loss of meaning and giving priority to things they wanted to do.” On the other hand, the parents recognized the future possibility of LDLT. Therefore, “Concern about the child thinking only of the present” emerged in the parents. This attitude of the parents seemed to cause “Growth of independence and feeling of being treated like a child” in the patients.

Whether patients recognized the possibility of LDLT did not seem to influence the relationship between patients and parents. In the case of not recognizing the possibility of LDLT, the patients did not understand that their parents were serious. On the other hand, even when they did recognize the possibility of LDLT, this was a delicate period for patients, such that they viewed the possible need for LDLT sometime, but not necessarily right away. In this way, the gap in recognition and attitudes toward the illness between the patients and parents was not improved.

Transition to life and looking ahead to the future: Conflict between patients and parents improved through friction caused by experiences of “Growth of self-management provided by a clue from experience” and “Child's mental growth: calm down rebel spirit.” Patients indicated that could express appreciation to their parents only after reaching late adolescence. In addition, parents began to “Appreciate the child's effort by keeping a proper distance” through life events of patients including attending higher education or getting a job. Afterward, patients and parents reached a stage in which they began to discuss constructively with each other. In the case that the conflict between patients and parents was serious, third party health professionals helped patients and parents to reconstruct their relationship.

The patients with biliary atresia surviving with their native liver, and their parents, were bewildered because of the ambiguous nature of biliary atresia, the possibility of LDLT, and characteristics of the adolescent developmental stage. At the time of the gap in recognition and attitudes toward the illness between the patients and parents, the patients and parents were bewildered respectively, which developed into friction or suffering. Therefore, nurses should understand the content of this suffering and the change process of these relationships.

For patients and parents, in order to reach the stage of Transition to life looking and looking ahead to the future, not only mental growth of the patient, but also accumulation of experience is important.7 Nurses should become the compensating factor to reconstruct patient-parent relationships and support patients in acquiring understanding of their illness and experiencing suitable developmental stages in school or society.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Hiratsuka. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.