MOJ

eISSN: 2475-5494

Opinion Volume 9 Issue 3

Economics, Policy & International Business Department, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK

Correspondence: John Simister, Senior Lecturer, Economics, Policy & International Business Dept, Manchester Metropolitan University, M15 6BH, UK, Tel 0161 247 3899

Received: April 26, 2020 | Published: May 22, 2020

Citation: Simister J. Is a woman more likely to experience violence, if she earns more than her partner? MOJ Women’s Health. 2020;9(3):67-70. DOI: 10.15406/mojwh.2020.09.00272

This paper is a replication of Simister1 which claims that if a woman earns more than her husband, she is more at risk of experiencing Gender-Based Violence (GBV). This paper uses a much larger set of household surveys, Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS); the new evidence supports the claims of the 2013 paper, and offers new perspectives. Female deference may be a way for a woman to protect herself from male violence.

The author is grateful that DHS survey data is made available to researchers. Any mistakes in this paper are the author’s responsibility.

Keywords: gender-based violence, demographic and health surveys

Space does not permit a literature review; readers are referred to Simister,1 which discusses various approaches–most of which are sociological. Other approaches include Grossbard,2 who analyses views of some economists: her own approach is impressive, but complicated.

Many sociologists are ambivalent about women’s earnings: they might allow a woman to walk away from a violent partner, but (if she stays with him) he may be unable to cope with his feelings of failure, if he cannot financially support his family. Rajkumari et al.3 wrote “The most common cause of violence (41.4%) as reported was ‘Arguments due to financial problem’. Financial dependency as well as less education may act as a precipitating factor for violence”.

This paper uses data from all relevant DHS surveys available in 2019, limited to female respondents (data on male respondents is not analysed here). In most DHS surveys, women are between 15 and 49 years old.4 This sample is restricted to women who are married/cohabiting in heterosexual relationships; the appendix shows effective sample-sizes for Figure 2 (Figures 1 and 3 have similar sample-sizes).

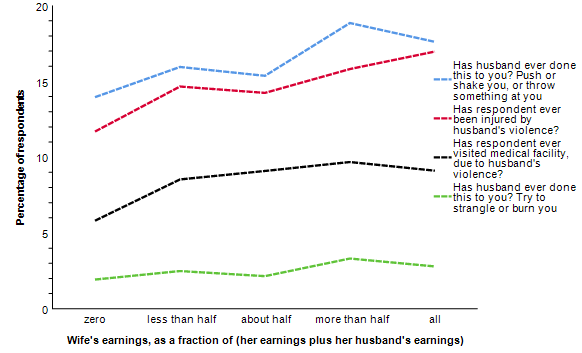

Figure 1 Respondent experienced types of violence, by her earnings.

Effective sample sizes: 550,551; 550,496; 131,645; and 55,257 cases respectively.

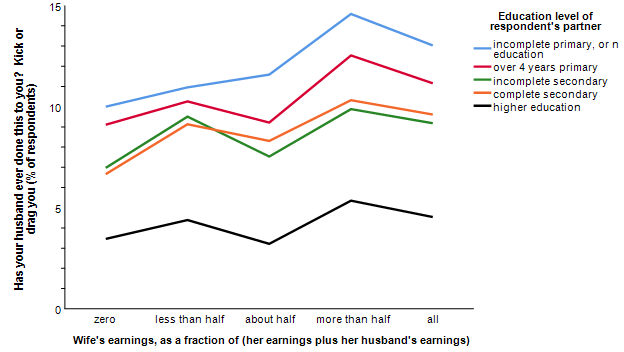

Figure 2 Respondent experienced violence, by her earnings & partner’s education.

Effective sample-size: 524,015 cases.

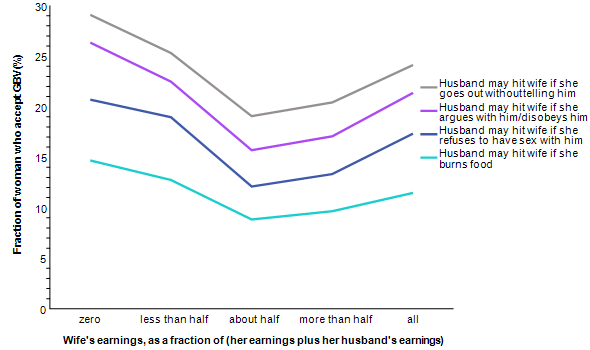

Figure 3 Women’s attitudes to GBV, by female earnings.

Effective sample-size: 24,663; 24,574; 23,254; 23,811 cases respectively.

The horizontal axis of Charts in this paper use variable v746: “Would you say that the money that you earn is more than what your husband earns, less than what he earns, or about the same? MORE THAN HUSBAND/LESS THAN HUSBAND/ABOUT THE SAME/HUSBAND HAS NO EARNINGS” (IIPS & ICF, 2017b: 74), combined with data-processing by the author to identify women with no earnings. Other questions investigated here include (for the vertical axis of Figure 3): “In your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife in the following situations: If she goes out without telling him?” (yes or no).5

Figure 1 aims to assess if claims by Simister1 are supported in DHS data. Each line is approximately horizontal, without the large spikes where the wife is the main earner; so the four lines in Figure 1 are less persuasive than Charts in Simister.1 Nevertheless, the key finding is confirmed: comparing left and right sides of Figure 1, there is more violence against a woman if she earns ‘more than half’ or ‘all’ of the household income (as opposed to ‘zero’, ‘less than half’ and ‘about half’). Note that a household can have more than two employed people, as well as non-earned income such as interest on savings; such complications are beyond the scope of this paper.

Madhivanan et al.6 state “women who contributed some household income were at significantly higher odds of being the victim of violence […] female employment typically functions as a protective factor only when a partner is also employed; if an employed woman is partnered with an unemployed or underemployed spouse, her risk of violence increases”. This view is consistent with Figure 1.

Figure 2 confirms Simister,1 in that there is a higher prevalence of violence on the right of Figure 2 (where the wife earned a large fraction of her & her partner’s combined income), than on the left (where women earned less). It seems puzzling that the level of violence is higher if the wife earns ‘less than half’ or ‘more than half’ of the couple’s income; this brief article does not attempt to answer such questions.

Figure 3 analyses how women with different (relative) earnings feel, regarding domestic violence. Among women with no earnings, about 30% say it acceptable for a husband to beat his wife–if she goes outside the home without his permission. But moving from left to right, we see decreasing acceptance of this idea: among women who earn about as much as their husband (‘about half’, on the horizontal axis), this falls from 30% to about 20%. Other attitude questions in Figure 3 show similar results. We might interpret Figure 3 as evidence that as women earn more, they support equal rights more; but this trend reverses on the right, as women become the main earners. There are several ways we could explain this: for example, many women who earn more than their husband have experienced violence themselves (Figure 1), which may affect their acceptance of GBV (regrettably for academics, many women may come to see GBV as ‘normal’).

We could consider a ‘symbolic interactionist’ view. A relatively well-paid woman realises that if a woman is the main earner in her family, her husband will find this humiliating; it is in her interests to placate him–for example, by being deferential, and doing more unpaid housework. Academics in a developed country may find such thinking unacceptable–a woman should never be a second-class citizen; but we cannot protect every woman in the world from violence, so supporting vulnerable women (who find their own solutions) may be appropriate. Gwagwa7 discusses such issues, as well as others relevant to household members’ behaviour–such as alcohol consumption.

Who understands how a household works? We might imagine that a woman will feel empowered if she is earning: she is less dependent on her partner–if he misbehaves, she can take her children and leave him. But this paper confirms evidence in Simister:1 male violence against women tends to increase (not reduce), if she earns more than he does. More research is needed.

Simister1 analysed surveys reporting husband & wife earnings, allowing the author to divide each sample into seven categories (rather than five, in this paper). Of the seven categories, the highest risk of GBV (by far) was in households where the wife earned between 83% & 99% of the couple’s joint income. DHS data are less precise: few DHS surveys report wife’s earnings, and no female respondents report their partner’s earnings. In other respects, DHS surveys are much better: they are nationally representative (sampling urban & rural households, and in many locations); whereas most surveys used by Simister1 only interview respondents in a few cities. Among surveys studied in Simister,1 BHPS is the most impressive; but DHS surveys cover many countries (see Appendix).

|

Country |

Year |

Sample |

|

Afghanistan |

2015 |

20159 |

|

Armenia |

2016 |

2824 |

|

Angola |

2015 |

5465 |

|

Azerbaijan |

2006 |

3619 |

|

Burkina Faso |

2010 |

8817 |

|

Burundi |

2016 |

5368 |

|

Benin |

2018 |

3754 |

|

Bolivia |

2008 |

9894 |

|

Democratic Republic of the Congo |

2013 |

4638 |

|

Cote D'Ivoire |

2012 |

4029 |

|

Cameroon |

2011 |

3233 |

|

Colombia |

2010 |

26582 |

|

Dominican Republic |

2007 |

6231 |

|

|

2013 |

4128 |

|

Egypt |

2014 |

6129 |

|

Ethiopia |

2016 |

3710 |

|

Gabon |

2012 |

3136 |

|

Ghana |

2008 |

1420 |

|

Gambia |

2013 |

2997 |

|

Guatemala |

2015 |

5682 |

|

Honduras |

2012 |

10331 |

|

Haiti |

2006 |

2217 |

|

|

2012 |

5623 |

|

|

2017 |

3729 |

|

India |

2006 |

62293 |

|

|

2015 |

60064 |

|

Jordan |

2007 |

2818 |

|

|

2012 |

5812 |

|

|

2017 |

5153 |

|

Kenya |

2009 |

4051 |

|

|

2014 |

3624 |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

2012 |

4301 |

|

Kampuchea |

2005 |

1578 |

|

|

2014 |

3125 |

|

Comoros |

2012 |

1893 |

|

Liberia |

2007 |

3208 |

|

Mali |

2018 |

2821 |

|

Myanmar |

2016 |

2913 |

|

Maldives |

2017 |

2758 |

|

Malawi |

2010 |

4415 |

|

Mozambique |

2011 |

4124 |

|

Namibia |

2013 |

1050 |

|

Nigeria |

2008 |

17274 |

|

|

2013 |

20209 |

|

|

2018 |

7952 |

|

Nepal |

2011 |

3278 |

|

|

2016 |

3542 |

|

Peru |

2005 |

2918 |

|

|

2006 |

3231 |

|

|

2007 |

3127 |

|

|

2008 |

7762 |

|

|

2009 |

11851 |

|

|

2010 |

8072 |

|

|

2011 |

11047 |

|

Philippines |

2008 |

6600 |

|

|

2013 |

7530 |

|

Pakistan |

2012 |

3383 |

|

|

2018 |

3770 |

|

Rwanda |

2010 |

2465 |

|

|

2015 |

1467 |

|

Sierra Leone |

2013 |

3713 |

|

Senegal |

2017 |

2185 |

|

Sao Tome and Principe |

2008 |

1396 |

|

Chad |

2015 |

3079 |

|

Togo |

2014 |

4413 |

|

Tajikistan |

2012 |

3926 |

|

|

2017 |

4461 |

|

East Timor |

2009 |

2034 |

|

|

2016 |

2928 |

|

Tanzania |

2010 |

4793 |

|

|

2015 |

6294 |

|

Ukraine |

2007 |

1860 |

|

Uganda |

2006 |

1199 |

|

|

2016 |

5822 |

|

South Africa |

2016 |

1664 |

|

Zambia |

2007 |

3426 |

|

|

2013 |

7535 |

|

Zimbabwe |

2010 |

3749 |

|

|

2015 |

4344 |

Appendix Effective sample-sizes for Figure 2

Evidence in this paper support the claim by Simister1 and others, that women tend to be more at risk if they earn more than their partner. Referring to India, Bhattacharya (2000:22)8 wrote “Socialization ensures that women accept their subservient roles in the household and perpetuate the discrimination against their female offspring […] ideology stresses male superiority within the household and places the women under the control of men throughout her life”. Madhivanan et al.6 found interventions aimed at increasing women’s job skills protect women (to some extent) against GBV; but “On the other hand, there is a risk that focusing primarily on providing opportunities for women to contribute some income to the household may actually put some at increased risk for physical violence. We suspect that partial contributions may upset the power dynamic in marital relationships without providing sufficient leverage to negotiate physical safety within the home [...] increasing a wife’s household contribution may exacerbate the risk of violence”.

There is general agreement among academics that more education for girls/women is appropriate. Figure 2 suggests male education is also important. If a man was socialised (as a boy) to believe he must be the family breadwinner and decision-maker, education could help him to reinvent himself as a ‘modern man’ if he finds himself unemployed.

None.

None.

©2020 Simister. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.