MOJ

eISSN: 2475-5494

Research Article Volume 8 Issue 1

Department of Economics, Policy & International Business, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK

Correspondence: John Simister, Department of Economics, Policy & International Business, Manchester Metropolitan University, All Saints, Manchester, M15 6BH, UK, Tel (0)161-247-3899

Received: January 31, 2019 | Published: February 6, 2019

Citation: Simister J. Are doctors getting the balance right? Treatment for depression in England, 1983 to 2017. MOJ Womens Health. 2019;8(1):78-84. DOI: 10.15406/mojwh.2019.08.00216

This paper investigates the risk of depression, and prescription of medical treatments for depression, among English women & men since 1983. It assesses some criticisms which have been made against medical healthcare professionals, such as their treatment of younger women with mental health problems. Some academics criticise doctors for over-prescribing anti-depressants; whereas other critics imply doctors often fail to prescribe treatment for depressed people. Many of these negative comments about English doctors seem unjustified, when assessed using survey data. This paper uses household surveys from 1983, to assess some aspects of the mental health problems and medical treatment experienced by survey respondents. Analysis of survey data, and qualitative information sources such as focus groups, may help doctors and other health professionals improve their work in future. Staff working for the National Health Service has much to be proud of; but there is more work to do.

Keywords: depression, anti, depressants, England, long-term trends, doctor

In UK, a ‘General Practitioner’ (GP) is a highly-qualified medical doctor, who carries out a key role in providing healthcare to the general population. Some writers, discussed below, have criticised GPs: for example, some people suggest GPs over-prescribe medication, whereas others claim that too few medicines are prescribed. Prescription of antidepressants in England doubled from 2005 to 2015;1,2 but this increase might be appropriate, if depression became more prevalent over this period. Some critics argue that GPs should offer different types of intervention, such as ‘Cognitive Behavioural Therapy’ (CBT); however, other people dismiss such “talking cures” as unscientific. Depression seems to be an increasing problem in UK; but it is hard to tell how many people in England are depressed. Previous researchers used various methods–such as the ICD-10 or DSM-5 approaches discussed below. These differences mean we often cannot directly compare findings from different research–such as on the prevalence of depression. Household surveys offer a perspective which might shed light on treatments for depression & other health issues–focusing on the patient’s perspective, rather than experience gained by GPs in their daily work. GPs could benefit from better understanding of how their patients feel: for example, do patients want to be involved in decisions about their own treatment? An advantage of household survey data is to reduce the ‘treatment gap’ (gaps in knowledge, because many people with depression don’t contact medical professionals): “only one-third of older people with depression ever discuss it with their GP”3–this may be at least partly because of social stigma.4

Introduction

This paper is too short to include all relevant research; it attempts to give a flavor of some controversies related to depression, and treatments for depression, in England. The author does not attempt to settle any controversy– the aim is to make readers more aware of some complicated debates. Analysing household survey data may improve understanding of this important topic. Academic analysis of publicly-available quantitative survey data could help GPs support their patients, complementing other sources such as qualitative surveys and NHS databases.

Defining ‘depression’

Depression is controversial. Medical experts disagree about why some people become depressed, whereas other people do not; and how a depressed person can best be treated. It may be desirable for GPs, psychologists, & psychiatrists to use a standard diagnostic system describing psychiatric disorders5 such as ‘Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders’, DSM-56 or ‘International Classification of Disease’ (ICD-10).7 There are similarities: “developers of the DSM-5 sought to maintain and, where possible, enhance the consistency of DSM and ICD”.8 An alternative system is ‘Research Domain Criteria’ (RDoC) from the USA National Institute of Mental Health.

DSM is highly respected–for example, Regier8 recommend DSM-5 for assessing mental health problems. But Cocchi, Tonello & Gabrielli9 claim “the development of DSM-5 was unduly influenced by input from the psychiatric drug industry. A number of scientists have objected that the DSM forces clinicians to make distinctions that are not supported by solid evidence, distinctions that have major treatment implications, including drug prescriptions”. Aho & Guignon10 claim psychiatrists developing DSM for depression & related illnesses had financial ties to drug companies selling medications for those illnesses.

DSM-5 separates ‘Depressive Disorders’ in Chapter 7, from ‘Anxiety Disorders’ in Chapter 8.6 DSM strict categorical boundaries give the impression that psychiatric disorders are discrete phenomena;8 but ‘Generalized Anxiety Disorder’ has similar symptoms to depression11,12–for example, DSM-5 ‘Major Depressive Disorder’ includes specifier "with anxious distress".13 Depression can be diagnosed in several categories of ICD-10, such as ‘Bipolar affective disorder’ (F31) or ‘Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder’ (F41.2).7

The previous paragraph suggests anxiety & depression are alternative diagnoses; but other observers consider anxiety cannot be clearly distinguished from depression–for example, NIMH report depression is “strongly comorbid” with multiple anxiety disorders.14 Sheldon sees anxiety & depression15 as being on a continuum.16 Callander & Schofield17 investigate ‘psychological distress’, which they define as “anxiety and depression symptoms, including nervousness, sadness, restlessness, hopelessness, and worthlessness”.

There is evidence that depression is often preceded by ‘anxiety disorder’.18–20 This may suggest anxiety is a cause of depression; it seems consistent with the RDoC approach, in which ‘Negative Valence Systems’ include ‘Potential Threat ("Anxiety")14–which is relevant to depression.15 Similarly, in ICD-10, ‘Mood [affective] disorders’ include “a change in affect or mood to depression (with or without associated anxiety)”: (F30 to F39).7 ICD-10 goes further, suggesting episodes of depression “can often be related to stressful events or situations” (F30 to F39).7 Martell et al. see depression as a response to difficult events: behaviour such as withdrawal, avoidance, and inactivity may be ‘coping strategies’.21

Sources such as NICE22,23 and Royal College of Psychiatrists24 offer guidance to UK medical personnel, on how to identify depression and anxiety. A typical UK psychiatrist might have about a decade of training, followed by decades of clinical experience; but a thousand years might not be enough to fully understand depression!

Are medical professionals helpful?

In UK, a GP is often the first medical professional a depressed person comes into contact with; the GP can prescribe medicine & other treatments, or refer a patient to a specialist such as a psychologist or psychiatrist. GP training includes how to interact with patients; doctors have sophisticated social skills. However, each GP would normally have conversations with dozens of patients each week – on average, a patient consultation with a GP only lasts for a few minutes. Some commentators seem unimpressed with GPs: “young women also came into regular contact with other professionals: doctors, mental health professionals and JCP work coaches. However, they did not describe a particularly positive or close bond with them. Sometimes young women would need support to go to health appointments or to negotiate with health professionals, as exemplified in the examples given in some of the accounts of the daily lives of young women with health problems”.25

Another case study said “I was hysterical when the first social worker came out and she was like, I think you’re depressed and you need to go back to the doctors. … So I had to go and then he increased my dosage but I was thinking I’m not even depressed. Well I was, obviously […] So I got that upped and I thought I don’t even want to take these anymore. I never even told my GP I just got myself off them”.25

Do UK doctors prescribe too many, or too few, anti-depressants?

Some observers imply GPs should have responded more strongly to depression: Lockhart & Guthrie26 wrote “In response to evidence that depression is often under-detected and under-treated, there have been a number of initiatives since the 1990s to improve diagnosis and treatment”. Reid27 claimed “depression is still under-recognised and undertreated”.

But others claim UK doctors over-prescribe anti-depressants.28 One GP claimed that GPs “use antidepressants too easily, for too long, and that they are effective for few people (if at all)”.29 Munoz-Arroyo30 claim increasing antidepressant prescribing can’t be explained by increasing prevalence of depression; the associated ‘Commentary’ by Chris Burton stated “If this is for maintenance therapy of major psychiatric disorder, then fine, but if a treatment that was offered (as the only thing available)31 during a difficult life episode is being continued, because of patient belief in its efficacy or the doctor’s adherence to guidelines for more serious illness, these results give real cause for concern”. In some cases, over-prescription of anti-depressants may be caused by long waiting-lists for ‘talking therapies’ such as CBT.32

Evidence reported by Munoz-Arroyo.30 seems unpersuasive: “It is possible that between 1995 and 1998 more people were being treated with antidepressants and their GHQ-12 scores may have improved. These improved scores would have been lost among the population as a whole. If they hadn’t been treated with antidepressants, it is conceivable that the true level of GHQ-12 caseness in the population would have increased. It is impossible to know if this happened or the size of this effect”.30

Summary

There is much disagreement on what depression is, and how to treat it. This paper cannot resolve these disagreements, but may encourage readers to investigate & report on it. The remainder of this paper reports relevant data from some household surveys, which shed light on these debates.

Data and methods

This paper uses data from numerous household surveys. ‘British Social Attitudes’ (BSA)32 are household surveys which have been carried out almost every year since 1983, covering various topics. The 2011 survey is particularly relevant to this paper, in asking about attitudes to doctors. The ‘British Household Panel Study’ (BHPS) is a national survey, based at the University of Essex,33 which interviewed a sample of several thousand people in 1991, and then attempted to re-interview each person once per year. The ‘Understanding Society’ survey began in 2009, conducted by the ‘Institute for Social and Economic Research’;34 it is a successor to BHPS, again using annual interviews. The BHPS sample forms part of Understanding Society from Wave 2; BHPS in this paper refers to ‘BHPS’ and ‘Understanding Society’.

The ‘Health Survey of England’ (HSE) is a large-scale, nationally-representative, sample of people interviewed each year from 1991; it is intended to monitor trends in the nation’s health.35 For this paper, HSE 1995 to 2012 respondents are considered to have been prescribed anti-depressants if any of variables MedBi01 to MedBi22 indicate the respondent was recently prescribed Tricyclic & Related Antidepressants (HSE code 40301, equivalent to British National Formulary code 4.3.1); Monoamine-Oxidase Inhibitors (code 40302); Selective Serotonin Re-Uptake Inhibitors (code 40303); or other anti-depressant medicine (code 40304). For HSE 2013 to 2016, variable antiDepM2 is used. HSE 2015 and 2016 report only the age-group of respondents; for comparability, other HSE surveys are recoded to the same age-groups for Chart 6.

The Labour Force Survey is one of the largest surveys commissioned in the UK. It is carried out by the UK government; findings are used to assess the UK economy, such as unemployment. LFS provides a long-term perspective of depression risk. In 1997, LFS questions changed to reflect the Disability Discrimination Act 1995: “new questions are concerned with all health problems, whilst until spring 1997 the emphasis has been on problems which affect respondents work”.36 Hence, for this paper, depression in LFS refers to people with depression sufficiently serious to limit their employment. At the time of writing, LFS data were only available to June 2018; hence, 2018 data are excluded from the sample, to reduce distortions caused by seasonal patterns. For Chart 3, LFS is limited to ages 16 to 64, for comparability between years.

Table 1 shows the sample-sizes used in this paper. Each survey in Table 1 (BSA, BHPS, HSE & LFS) is designed to provide a nationally-representative sample; they are very large samples. For this paper, weighting is not used to correct for possible sampling imperfections. Sample-sizes in Table 1 are generally the number of people of people interviewed in each sample; for BHPS however, most people are re-interviewed each year– hence, numbers in the BHPS column are appropriate for variables where each person can report different answers each year. The ‘Hawthorne effect’ may influence BHPS evidence; increasing ages of BHPS respondents since 1991 might reduce the representativeness of the sample. This paper uses all data available at the time of writing, for surveys in Table 1. Each survey analysed for this paper was accessed via the UK Data Archive/Data Service.

Year |

BSA |

HSE |

LFS |

BHPS |

1983 |

1,494 |

|||

1984 |

1,407 |

100,149 |

||

1985 |

1,538 |

103,753 |

||

1986 |

2,623 |

105,389 |

||

1987 |

2,402 |

103,304 |

||

1988 |

104,845 |

|||

1989 |

2,571 |

105,253 |

||

1990 |

2,395 |

101,643 |

||

1991 |

2,490 |

3,242 |

100,210 |

8,774 |

1992 |

4,416 |

307,167 |

8,186 |

|

1993 |

2,503 |

17,687 |

410,378 |

7,905 |

1994 |

2,979 |

15,809 |

401,936 |

8,218 |

1995 |

3,098 |

19,788 |

405,293 |

7,878 |

1996 |

3,054 |

20,328 |

398,370 |

8,406 |

1997 |

1,153 |

15,546 |

382,810 |

9,272 |

1998 |

2,695 |

19,654 |

384,371 |

9,160 |

1999 |

2,718 |

9,640 |

379,589 |

8,356 |

2000 |

2,887 |

9,920 |

374,256 |

9,573 |

2001 |

2,761 |

19,640 |

365,294 |

8,907 |

2002 |

2,897 |

18,396 |

361,474 |

7,776 |

2003 |

3,709 |

18,553 |

349,889 |

7,780 |

2004 |

2,684 |

8,354 |

332,478 |

7,438 |

2005 |

3,643 |

13,297 |

334,588 |

7,702 |

2006 |

3,666 |

21,399 |

335,354 |

7,576 |

2007 |

3,528 |

14,386 |

329,437 |

7,357 |

2008 |

3,880 |

22,620 |

319,427 |

7,136 |

2009 |

2,917 |

8,382 |

315,456 |

20,613 |

2010 |

2,795 |

14,331 |

292,163 |

42,373 |

2011 |

2,859 |

10,617 |

282,084 |

40,718 |

2012 |

2,793 |

10,333 |

274,608 |

36,737 |

2013 |

2,799 |

10,980 |

258,289 |

34,900 |

2014 |

2,449 |

10,080 |

257,984 |

33,821 |

2015 |

3,778 |

13,748 |

244,451 |

34,421 |

2016 |

2,525 |

10,067 |

237,204 |

18,349 |

2017 |

238,237 |

1,407 |

Table 1 sample-sizes of the surveys used, by year

Source: author’s analysis.

Most evidence in this paper is shown as charts. To improve comparability, all Charts in this paper uses the same time-period (1983 to 2017)–even though each set of surveys was only carried out for some of those years.

Chart 1 is an index, based on a Likert scale from zero (very satisfied) through 50 (neither satisfied nor dis-satisfied) to 100 (very Dis-satisfied). In Chart 1, the index is around 25 to 30 over this period; the maximum possible value is 100, so more respondents were more satisfied than dis-satisfied. Chart 1 shows men more dis-satisfied with their GP than women, for most of the period since 1983–but women became slightly more dis-satisfied than men from 2011 (gender differences are small: blue & red lines in Chart 1 are never far apart). There’s a weak upward trend in women’s dis-satisfaction from 1983 to 2016; if women became slightly less happy with their GP, can we tell why? One source is the 2011 BSA survey, which asked ‘Who would you prefer to make decisions about your care?’-as shown in Table 2, women tend to seek more involvement in healthcare than men. This question isn’t asked in other BSA surveys, as far as the author is aware. Table 3 asks for opinions on doctors–presumably each respondent included their own experience in this assessment, but may also have considered experiences of people they knew. Table 3 shows strong support for doctors in England, among women & men.

Who would you prefer to make decisions about your care? |

Gender of respondent |

||

Male |

female |

||

Your doctor or health professional, based on their expertise |

31% |

21% |

|

You, based on your experience and knowledge |

4% |

4% |

|

You and your doctor or health professional make the decision together |

64% |

75% |

|

|

Total |

100% |

100% |

(417 cases) |

(526 cases) |

||

Table 2 Respondent’s attitudes to their own healthcare, by gender

Source: BSA 2011 (author’s analysis). The difference between women & men is statistically significant (p-value=0.001 based on a Pearson Chi-square test).

Maguire & Mckay25 wrote: “Other young women did not like tablets because of their previous issues with dependency or because they physically could not take tablets. However, either the doctor prescribing did not ask them how they felt about taking tablets or they did not feel confident enough to voice their discomfort with the prescription”. This seems inconsistent with general support for GPs in Chart 1 & Table 3. Qualitative evidence, such as focus groups, can be helpful; but GPs shouldn’t over-react to relatively small numbers of people in a typical qualitative study. This author does not suggest Maguire & Mckay are unjustified in criticising GPs; but recommends considering several information sources. GPs should be considered ‘innocent until proven guilty’.

Do you respect Doctors? |

Gender of respondent |

||

Male |

Female |

||

A great deal of respect |

66% |

69% |

|

Some respect |

31% |

29% |

|

Not a lot of respect |

2% |

1% |

|

No respect at all |

1% |

0% |

|

|

Total |

100% |

100% |

(1,925 cases) |

(2,516 cases) |

||

Table 3 Respondent’s opinion on doctors, by gender

Source: BSA 2011 (author’s analysis). The difference between women & men is statistically significant (p-value=0.0003 based on a Pearson Chi-square test).

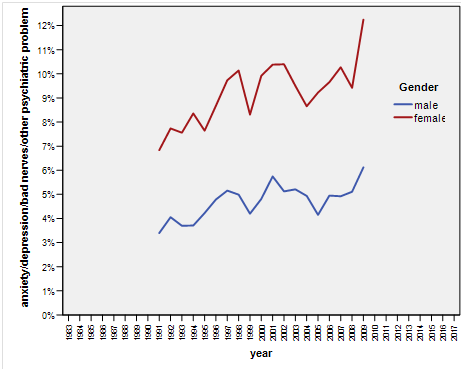

Chart 2 shows clear evidence that the number of anti-depressant medicines prescribed in England rose dramatically from 1995. This trend is consistent with previous research, such as Moore37 from 1993 to 2005; and Prescribing and Medicines Team (2016: 29) from 2005 to 2015. Some people question whether upward trends (in Chart 2) are appropriate–could English GPs be over-prescribing anti-depressants? Charts 3 to 5 offer evidence, reporting long-term trends in depression prevalence. Chart 3, using LFS data, shows increasing prevalence in depression which limits the victim’s ability to do paid work; it suggests a large increase in depression prevalence–and hence it is appropriate for GPs to provide more treatment for depression. Whether anti-depressants are the best treatment for depression is a separate question–it is beyond the scope of this paper to assess whether CBT would have been more appropriate than anti-depressants for (some) patients. Chart 4 uses alternative evidence to Chart 3, to assess whether or not depression prevalence increased. BHPS surveys asked “Do you have any of the health problems or disabilities listed on this card? .…Anxiety, depression or bad nerves, psychiatric problems”.33 Chart 4 shows an upward trend.

Chart 5 again investigates the prevalence of depression, using ‘Understanding Society’ surveys–which asked: “How much of the time during the past 4 weeks... Have you felt downhearted and depressed?” (Variable SCSF6C).34 For Chart 5, answers were recorded by the author to this index: ‘all of the time’ given a score of 100; ‘most of the time’ scored 65; ‘some of the time’ scored 15; ‘a little of the time’ scored 5; and ‘none of the time’ a score of zero.

Charts 4 & 5 confirm the upward trend in Chart 3: there is a clear tendency for increased depression prevalence in UK, in recent decades–for women and men. In each chart of this paper, variables adopted are comparable over time; but readers should be aware that there is little agreement on how we should measure depression–it isn’t clear which Chart to focus on.

Charts 3 to 5 may persuade some readers that depression is increasing–in which case, increases in anti-depressant medication could be justified; but perhaps prescribing a type of counselling (such as CBT) would be preferable to tablets; combining CBT with anti-depressant medicine might be optimal.38 If anxiety is inter-related with depression, then anxiolytics might help. But if medical professionals are accused of excessively prescribing anti-depressants (based on Chart 2 or similar evidence), Charts 3 to 5 seem to justify these doctors’ decisions. It can be argued that female patients should receive more help to cope with depression–for example, many women experience post-natal depression. But Maguire & Mckay25 imply young women face barriers when seeking help from doctors; should GPs pay more attention to young women, and treat men & older women as less important? Chart 6 doesn’t seem to support Maguire & Mckay, because the highest prevalence of anxiety/depression is among women/men in their 50s; there seems little justification to spend more on young adults than middle-aged patients.

Chart 4 People with anxiety/depression/bad nerves/psychiatric problem, by year & gender.

Source: BHPS (author’s analysis).

Medical professionals disagree on what depression is, and how to treat it. This paper does not attempt to assess which group of experts (e.g. DSM, ICD, or RDoC) has the ‘best’ approach to understanding depression. This paper does not attempt to explain why depression occurs, or why prevalence rates are rising; more research is needed.

Munoz-Arroyo,30 studying Scotland, found no evidence to support any of the four potential explanations for increasing antidepressant prescribing in Scotland that they investigated: “there was no evidence of an increase in the incidence or prevalence of depression; people did not present more often to their GPs with symptoms leading to a diagnosis of depression; and GPs did not record more diagnoses of depression”. Referring to England from 1998 to 2012, Spence38 wrote “Although there has been a recent increase in the prevalence of depression recorded by GPs, this change cannot fully account for the increased dispensing of antidepressants”. Johnson39claimed “Although prescribing continues to increase, there has been no corresponding increase in depression incidence or prevalence”. This paper rejects their findings, for England: depression prevalence did increase dramatically between 1984 and 2017, as shown in Charts 3 to 5.

This paper focuses on England, because ‘Health Survey of England’ is a key data source. For comparability, all other surveys used in this paper are limited to England. It is possible that many aspects of the findings in this paper would apply to the UK as a whole–further research could improve knowledge, and help GPs support patients. One topic in this paper is increasing anti-depressant use since the 1990s: did GPs make a mistake, and dispense too many tablets? Some researchers reported in this paper suggest GPs over-prescribed; other researchers claim the opposite. Evidence in this paper suggests that (in general) GPs seem justified in increasing prescription of anti-depressants, because the number of people describing themselves as depressed increased dramatically (as shown in Charts 3 to 5). The question of whether other treatments such as CBT would be more appropriate than medication is not assessed in this paper. Medical professionals such as GPs spent years training, and most have years of experience–often observing patients before & after treatment they prescribe. Academics can review past data, and assess how well GPs performed–some writers imply they know better than medics. Is such criticism justified? We should not see doctors as victims: GPs can prescribe or withhold treatment, and even ‘section’ a patient (force them to stay in a mental hospital against their will). A GP is more powerful than a patient.

This paper draws on household surveys over decades which interviewed over ten million people. GPs may feel vindicated–many criticisms against them seem weak: patients are generally supportive of doctors. Doctors helped millions of people in England since 1983; it seems clear that increasing anti-depressant prescription is a justified response by GPs to increasing depression prevalence. Academics can play a positive role, for example by analysing survey data; if a reader has evidence that GPs could do better, then publish it. Evidence in this paper suggests some researchers are too ready to criticise medical professionals–such criticisms may discourage some people from seeking help. Commentators (including those referred to in this paper) should be careful not to inhibit depressed people from visiting their doctor: if a woman is depressed, she is likely to get more help from her GP than from a statistician. Maguire & Mckay didn’t interview ten million people; but–in the author’s opinion–their evidence is compelling, explaining how disempowered women with mental health problems feel. Doctors can be proud of their achievements–but still aim higher.

The author is grateful to data providers, including UK government agencies, University of Essex, NatCen, and Institute for Social and Economic Research.

The author declares there are no conflicts of interest.

©2019 Simister. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.