MOJ

eISSN: 2574-9935

Case Report Volume 8 Issue 3

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Unidade Local de Saúde Viseu Dão-Lafões, Portugal

Correspondence: Pedro Leonel Almeida, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Unidade Local de Saúde Viseu Dão-Lafões, Portugal,

Received: October 27, 2025 | Published: November 3, 2025

Citation: Almeida PL, Félix T, Coelho P, et al. Intramuscular degloving injury of the rectus femoris: a case report and review of the literature. MOJ Sports Med. 2025;8(3):96‒98 DOI: 10.15406/mojsm.2025.08.00191

Intramuscular degloving injuries of the rectus femoris are rare but clinically significant lesions, characterized by separation of the inner bipennate (indirect) muscle component from the outer unipennate (direct) component. Recognition is essential, as these injuries differ from classic musculotendinous strains in both imaging appearance and prognosis.

We report the case of a 31-year-old male amateur soccer player who presented with right anterior thigh pain of sudden onset during training. Physical examination and radiologic findings are presented later in the article. This case highlights the importance of recognizing intramuscular degloving lesions, a distinct injury pattern described in the literature through MRI series and case reports. The pathophysiology, diagnostic imaging, management strategies, and outcomes are reviewed with reference to scientific evidence.

Muscle injuries of the lower limb are common in sports, with the rectus femoris (RF) being particularly susceptible due to its biarticular nature and unique internal architecture. Unlike other quadriceps muscles, the RF has two tendinous origins: a direct head from the anterior inferior iliac spine and an indirect head from the superior acetabular rim. These converge and extend into two distinct muscular components - an inner bipennate portion enveloped by an outer unipennate layer.1,2

This “muscle-within-a-muscle” anatomy predisposes the RF to a distinct form of injury termed intramuscular degloving, in which the inner component separates from the outer muscle fibers along a fascial plane.3,4 The lesion represents approximately 9% of rectus femoris injuries in some MRI series and is typically seen in athletes involved in kicking sports.3 Early diagnosis is essential, as the condition may be mistaken for a simple strain or hematoma, delaying appropriate management.5

A 31-year-old male amateur football soccer player, previously healthy, presented with right anterior thigh pain of sudden onset during a kick at training four weeks

before the appointment. The patient described a mechanical-type pain associated with a sensation of pressure in the anterior mid-thigh and difficulty performing soccer movements such as passing and kicking. Despite the discomfort, he was able to continue light activity. The was no report of previous injuries. The patient provided informed consent for the use of his clinical data in an open-access journal. A written and signed consent statement from the patient was submitted to the journal.

On examination, there was a palpable swelling over the middle third of the right thigh that became more prominent during resisted knee extension. Pain was elicited on active contraction and on resistance testing of the quadriceps. No neurological deficits were observed, and hip and knee joint motion remained full.

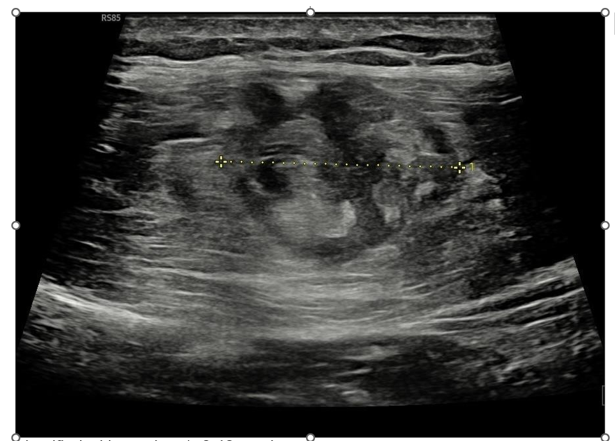

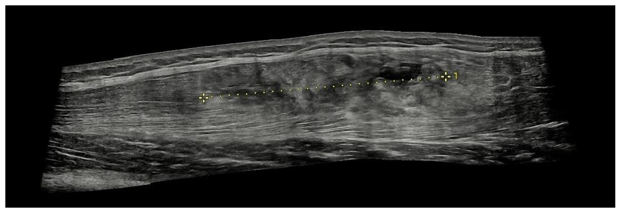

Ultrasound imaging revealed an intramuscular fluid collection and partial separation of the muscle fibers within the rectus femoris, consistent with an intramuscular degloving lesion (Figure 1&2).

Figure 1 Tranverse ultrasoud image of rectus femoris muscle

Measure identified with number 1: 2.42 centimeters.

Figure 2 Panoramic longitudinal ultrasound image of rectus femoris muscle

Measure identified with number 1: 7.48 centimeters.

Given the subacute presentation (four weeks since symptom onset) and imaging findings, no aspiration of fluid was performed. The patient was advised to suspend competitive sports activity and initiated a rehabilitation program including rest, cryotherapy, gradual stretching, and progressive strengthening.

At eight weeks, the patient reported complete resolution of pain and had returned to full football training without limitations.

Anatomy and biomechanical

The rectus femoris (RF) is uniquely predisposed to intramuscular degloving injury because of its dual-head arrangement: the outer unipennate (direct) component wraps around an inner bipennate (indirect) component, creating a potential plane of cleavage between them.2 The internal tendon (intramuscular aponeurosis) of the indirect head runs within the musculature, and this “muscle-within-a- muscle” architecture is rarely seen in other skeletal muscles.4 The result is that forces applied eccentrically or during forceful hip flexion plus knee extension can generate shear stress along this interface, pulling the inner component away from its sheath - hence the degloving phenomenon.2–4

Biomechanically, when the RF contracts eccentrically (as in deceleration or kicking), the outer and inner fibers may not always uniformly transmit load. Differences in fiber orientation, pennation angle, tendon stiffness, and load distribution may render the interface vulnerable to separation under high stress. The degloving lesion can thus be conceptualized as an intramuscular “slip plane” injury, where one muscular subcomponent shears within the larger muscle body rather than rupturing at a tendon or myotendinous junction.1,2

Interestingly, the exclusivity of reported intramuscular degloving injuries to the RF in the literature may reflect its unique architecture; to date, analogous intramuscular degloving in other muscles has rarely been documented, though a recent case series described a degloving-type lesion in the semimembranosus - expanding the conceptual boundaries of this lesion type. That said, the RF remains the archetypal site given its classical muscle-within-a-muscle design.6

Clinical spectrum and timing of presentation

Clinically, patients with IDI of RF commonly present with acute or subacute onset of anterior thigh pain, sometimes associated with a feeling of fullness or a “lump” in the mid-thigh region. The pain is reproduced by resisted knee extension or hip flexion, and mild swelling or tenderness is often present on palpation.3,7,8 In some cases, patients may continue activity at a reduced intensity or delay presentation because symptoms are less dramatic than with full-thickness tears.

In our case, the patient’s presentation aligns classically: sudden onset during training, mechanical pain, and palpable swelling. The relatively early recognition and use of imaging likely contributed to a favorable recovery trajectory.

Imaging signatures and their prognostic value

MRI remains the diagnostic gold standard for IDI, because it offers high spatial contrast to delineate the separation between inner and outer components. The defining MRI signature includes a circumferential fluid or edema signal at the interface, with edema in both the inner and outer compartments, often extending over multiple slices.2,4 In axial T2/STIR or fat-suppressed images, one may see a “ring” or “halo” of fluid around the dissociated inner muscle, sometimes described as a “finger-in-a-glove” pattern.4 Proximal retraction of the inner bipennate segment is seen in some cases, measured in millimeters or centimeters, and is an important prognostic marker.2

Kassarjian et al. documented separations ranging from a few centimeters up to about 18 cm and noted that retraction beyond certain thresholds tends to delay recovery.2 In the kickball case reported by Meller et al., there was ~23 mm retraction and a pronounced fluid collection, which required cautious rehabilitation.4 In contrast, in our patient, the favorable recovery suggests that retraction (if present) was modest and the lesion size was within a manageable scope.

Though less specific, ultrasound offers useful initial assessment: hypoechoic fluid collection, subtle fiber separation, and altered echotexture in the inner muscle portion may be visible, especially with high-frequency probes. In our case, ultrasound revealed the fluid plane and fascial separation, consistent with IDI. However, its sensitivity for quantifying retraction or distinguishing subtle separation is limited. Thus, MRI remains essential for comprehensive evaluation and prognostication.2,4

Some centers use contrast-enhanced MRI or delayed imaging to better delineate hemorrhage, granulation tissue, or capsular involvement, but such protocols have

not been extensively reported in the IDI literature. Additionally, repeat MRI over time may document resolution of fluid or reattachment of the inner component, although only a few published cases include longitudinal imaging data.

Management

Conservative management remains the standard of care in all published IDI cases. Key treatment principles include:

Given the fibrous nature of the interface, cautious progression is key. Some authors suggest delaying eccentric loading until imaging shows reduction or stabilization of fluid and edema, especially when the separation is larger.4

There is no consensus on hematoma aspiration in IDI. In some muscle injuries, ultrasound-guided aspiration of large collections may relieve pressure and pain, and theoretically aid healing; but in IDI, because the fluid is often between muscle layers rather than in a discrete hematoma cavity, the utility remains speculative. None of the published IDI cases systematically used aspiration; most favor letting the body resorb the fluid while focusing on rehabilitation.2,4

Prognostic factors

From the literature and our case, several potential prognostic factors emerge:

In our patient, the eight-week return suggests favorable prognostic features: modest retraction, early recognition, and disciplined rehabilitation.

Comparative reflection: degloving vs. other rectus femoris injuries

A valuable perspective is to contrast IDI with proximal rectus femoris avulsions or full-thickness myotendinous ruptures. In avulsion injuries, tendon is detached from bone, often requiring surgical fixation, and recovery often spans 3 to 6 months.10,11 Meanwhile, standard muscle or myotendinous strains have variable timelines (1-6 weeks) depending on grade and location.

Unlike avulsion or complete tears, IDI spares the primary tendon insertions and preserves continuity of the outer fibers, which may explain why rehabilitation is faster and surgical intervention rarely needed. The “intramuscular slip” nature of IDI places it somewhere between a high-grade strain and a distinct structural lesion-requiring its own rehabilitative nuance rather than being classified with traditional muscle injuries.2,9

Intramuscular degloving injuries (IDIs) of the rectus femoris represent an uncommon yet clinically significant differential diagnosis for anterior thigh pain in athletes. A high index of suspicion is warranted in individuals presenting with mid- thigh pain following activities involving forceful kicking or eccentric quadriceps loading, particularly when a palpable mass or localized fullness is detected. Prompt imaging evaluation is essential for accurate diagnosis and management planning. While ultrasound may serve as an initial screening tool, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) remains the diagnostic modality of choice, providing superior delineation of the intramuscular shear plane and the extent of myofascial retraction. Management is predominantly conservative, emphasizing a structured, phase-based rehabilitation program that progressively restores strength and function. Surgical intervention is reserved for atypical presentations or cases demonstrating inadequate response to nonoperative treatment. Patient education and adherence to prescribed rest and graded activity modification are critical in preventing lesion propagation and facilitating optimal recovery. Serial imaging may assist in monitoring healing progression and verifying reattachment, particularly in delayed or complex recoveries. Pathophysiologically, the injury results from shear separation between the inner (direct) and outer (indirect) components of the rectus femoris. When identified early and managed through a multidisciplinary approach, outcomes are generally excellent, with most athletes achieving full functional recovery and return to play. Further research, including multicenter registries, prospective cohort studies, and standardized imaging follow-up, is warranted to refine prognostic markers and optimize rehabilitation protocols.

Authors received no specific funding for this work.

None.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

©2025 Almeida, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.