MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6162

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 2

1Servicio de Cirugía General, Hepatobiliar y Trasplante Hepático, Pancreático e Intestinal. Hospital Universitario Fundación Favaloro, Argentina

2Servicio de Cirugía HPB y Unidad de Trasplante Hepático. Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Argentina

3Servicio de Cirugía Hepato-pancreato-biliar, Hospital Alemán de Buenos Aires, Argentina

4Servicio de Cirugía Pancreática, Sanatorio Trinidad Mitre, Argentina

5Servicio de Cirugía HPB, Hospital Italiano de Bahía Blanca, Argentina

6Servicio de Cirugía HPB y Trasplante Hepático, Sanatorio Sagrado Corazón, Argentina

7Grupo Especializado del Aparato Digestivo, Clínica de Nefrología, Urología y Enfermedades Cardiovasculares, Argentina

Correspondence: Juan Santiago Rubio, Servicio de Cirugía General, Hepatobiliar y Trasplante Hepático, Pancreático e Intestinal. Hospital Universitario Fundación Favaloro, Address- 1493 Tapiales St.Vicente López, Buenos Aires, Argentina, Tel +54 9 1130345656

Received: September 11, 2022 | Published: September 23, 2022

Citation: n: Rubio JS, Glinka J, Balmer M, et al. The pancreas as a target organ for metastases: Multi-center study in Argentina. MOJ Surg. 2022;10(2):31-35. DOI: 10.15406/mojs.2022.10.00199

Background: The pancreas is an uncommon site for metastases, accounting for 0.25% to 5% of pancreatic tumors, so that solitary pancreatic metastases are rare. The most frequent primary tumor capable of metastasizing in the pancreas is clear cell renal carcinoma (CCRC). Surgical resection remains the best therapeutic alternative to achieve long-term survival. Our aim is to present the long-term results of a multi-center study in Argentina of pancreatic resection due to pancreatic metastases.

Methods: Multi-center, retrospective report of adult patients operated for pancreatic metastases from July 2010 to December 2019, in 7 high volume Argentinian HPB surgery centers.

Results: 1557 pancreatic surgeries were performed, 48 (3.1%) due to pancreatic metastases. Median age was 62±11 years, 25 (52%) male. Twenty-six distal pancreatectomies, 12 pancreatoduodenectomies, 5 total pancreatectomies, 1 central pancreatectomy and 4 tumor enucleations were performed. The most frequent primary tumor was CCRC (N=35) followed by colorectal cancer (N=4). Mean number of pancreatic lesions was 1.6±3. Twenty-two (45%) patients had complications and 5 (10%) patients required reoperation; the 90-day mortality rate was 4.2%. Mean follow-up was 80 months. The mean disease-free interval was 5.3±6 years. The disease-free and overall survival was better in patients with pancreatic metastases of clear cell renal carcinoma compared with other type of cancer.

Conclusion: Despite its rarity, pancreatic metastases must be considered as a possible diagnosis in patients with a prior oncological history; surgical resection remains as the main therapeutic option.

Keywords: Pancreatic metastases, clear cell renal carcinoma, surgical resection

The pancreas is an uncommon site for metastases, representing only 0.25% - 5% of pancreatic tumors.1–4 The most common primary tumor responsible for causing metastases is clear cell renal carcinoma (CCRC), followed by colorectal cancer; other tumors such as melanoma, breast or lung cancer are less frequent.5–8 Pancreatic metastases (PM) are asymptomatic in 50% of cases, so most of them are diagnosed during the follow-up. The most common symptoms are gastrointestinal bleeding, weight loss, jaundice, pancreatitis, and diabetes.9 Although pancreatic resections have historically been associated with high morbidity and mortality, results have evolved when those procedures are performed in experienced centers.

Several studies have demonstrated that pancreatic resection for PM improves long-term results,10 increasing 5-year-survival rates from 51% to 88%, with a disease-free survival of 44 months. On the other hand, when patients were not resected, 3 and 5-year-overall survival was 21% and 0% respectively.9,11 The aim of this paper is to analyze the incidence, type of procedures performed, complications rate and long-term results of pancreatic resections due to PM in a cohort of cases reported as part of multi-center study carried out in Argentina.

This is a multi-center, retrospective analysis of a prospectively collected database of adult patients operated for PM, between July 2010 and December 2019. The appearance of PM 12 months after the diagnosis of the primary tumor was an inclusion criteria. Primary pancreatic tumors, synchronic metastases, and disseminated disease were excluded. Demographics, primary tumor histology, time from diagnosis of primary tumor and diagnosis of PM, type of surgery, reoperation rates, hospital length of stay, as well as overall and disease-free survival were analysed.

Complications were classified according to Dindo-Clavien classification,12 and pancreatic fistulas according to the International Classification Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula.13 Overall and disease-free survival were calculated from the date of pancreatic resection to the end of follow-up, recurrence or patient death.

Statistical analysis: Continuous variables are presented as average±standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables as a total number and percentages. The comparison of the continuous variables was performed by Student's test and categorical variables with Chi square and Fisher's test. Overall and disease-free survival were analysed using Kaplan-Meier curves and considered statistically significant when P = <0.05 (Log Rank test and Breslow test). For statistical analysis SPSS®v.25 package (IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 25.0 – NY, USA) was used.

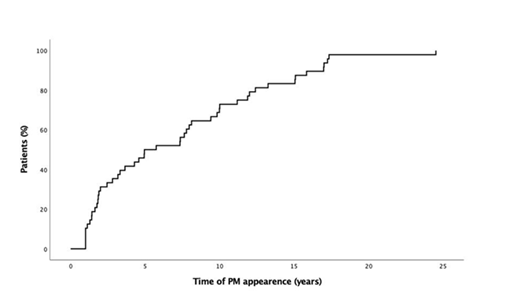

During the studied period, 1557 pancreatic surgeries were performed at the 7 centers. Forty-eight (3.1%) were due to PM. Mean age was 62±11 years, 25 (52%) patients were male; 37 (77%) had comorbidities. There were 35 patients with metastasis from CCRC, 27 placed on the right kidney tumor and 8 on the left kidney (p= 0.002). The other non-CCRC PM were: 4 (8%) colorectal cancer, 2 (4%) skin melanomas, 2 (4%) uterus (1 adenocarcinoma and 1 sarcoma), and 1 (2%) breast adenocarcinoma, 1 prostatic adenocarcinoma, 1 gastric GIST, 1 soft tissue sarcoma and 1 germinal tumor of testicle. Mean time from resection of the primary tumor to the appearance of PM was 5.2±7 years and 14 (29%) PM appeared beyond 10 years (Figure 1). Eighteen (38%) patients were symptomatic: 9 with abdominal pain; 2 abdominal pain and mass, 3 gastrointestinal bleeding, 1 exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, 1 jaundice, 1 loss of weight and 1 pruritus and the others were asymptomatic and diagnosed during follow-up.

Figure 1 1 Log Kaplan-Meier curve for disease –free interval (from surgery of primary tumor to PM resection.

Twenty-six distal pancreatectomies, 12 Whipple’s procedures, 5 total pancreatectomies, 1 central pancreatectomy and 4 tumor enucleations were performed. Mean number of pancreatic lesions was 1.6±1.3; 36 patients (75 %), had a unique PM. Twenty tree PM (47%) were localized in the body of the pancreas, being the most frequent site. Lymph nodes were compromised more frequently in patients with non-CCRC than in CCRC (p= 0.021). Resection margins were more commonly positive in non-CCRC than in CRCC (p= 0.005). Twenty-two (45%) patients had complications, the most frequent complication was type A pancreatic fistula (12%), followed by abdominal collection (8%), and 5 (10%) patients required reoperation; the 90-day mortality rate was 4.2% and the mean length of stay was 12±10 days. Mean follow-up was 80 months.

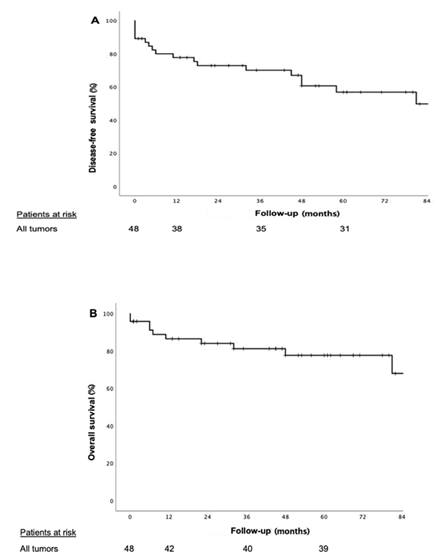

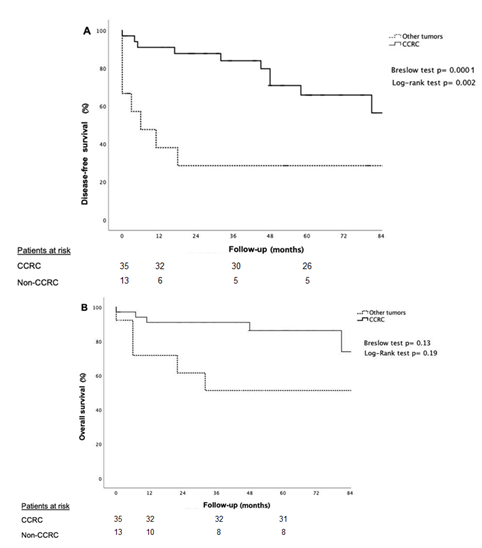

The disease-free survival of all patients at -1, -3 and -5 year was 77%, 70% and 56% respectively and the overall survival at -1, -3 and -5 year was 86%, 81, and 77% respectively (Figure 2). Patients with non-CCRC PM had statically significant local recurrence compared to the CCRC patients (p= 0.001). Recurrence sites are shown in Table 1. Patients with PM of CCRC had better -1, -3 and -5 disease-free survival compared with non-CCRC (91%, 83% and 65% vs. 38%, 38% and 29%; p= 0.002); and -1, -3 and -5 overall survival (91%, 91% and 86% vs. 71%, 51% and 51%; p= 0.019) respectively (figure 3). The appearance of the PM during the first 5 years after primary tumor surgery, did not impact on the disease-free and overall survival. Table 2 summarizes the results of literature review regarding pancreatic resections for PM, in order to be compared to our results.

Figure 2 Kaplan-Meier curves for patients undergoing pancreatic resection of all types of tumors (A) disease-free survival (B) overall survival.

Figure 3 Kaplan-Meier curves for patients undergoing pancreatic resection for CCRC vs non CCRC (A) disease-free survival (B) overall survival.

|

|

All |

CCRC |

Non-CCRC |

P value |

|

N (%) |

48 (100) |

35 (73) |

13 (27) |

0.0001 |

|

Sex (M/F) |

25/23 |

22/13 |

3/10 |

0.014 |

|

Age, mean (SD) |

62 (11) |

61 (11) |

55 (9) |

NS |

|

Comorbidities, n (%) |

37 (77) |

27 (77) |

10 (77) |

NS |

|

Right kidney/Left Kidney |

- |

27/8 |

- |

0.002 |

|

Symptoms |

||||

|

None Abdominal pain only |

30 9 |

25 7 |

5 2 |

0.03 |

|

GI bleeding |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Abdominal pain and mass |

2 |

- |

2 |

|

|

Pruritus Loss of weight Exocrine insufficiency Jaundice |

1 1 1 1 |

- - - 1 |

1 1 1 - |

|

|

Type of Surgery Pancreatoduodenectomy Distal pancreatectomy Total pancreatoduodenectomy Central pancreatectomy Tumor enucleation |

12 5 26 1 4 |

9 4 19 1 2 |

3 1 7 - 2 |

|

|

Lymph nodes +, n (%) |

17 (35) |

9 (25) |

8 (61) |

0.021 |

|

Resection margins +, n (%) |

5 (10) |

1 (3) |

4 (30) |

0.005 |

|

Complications, n (%) Clavien I Clavien II Clavien IIIA Clavien IIIB |

22 (45) 5 9 3 5 |

18 (51) 4 7 3 4 |

4 (30) 1 2 0 1 |

NS |

|

Length of stay, mean days (SD) |

12 (10) |

13(11) |

12 (7) |

NS |

|

Recurrence* (%) Liver Local Bone Lung Brain Peritoneum |

16 (33) 5 4 4 1 2 1 |

8 (22) 3 0 4 1 1 0 |

8 (61) 2 4 0 0 1 1 |

0.02 |

|

Persistence (%) |

4 (11) |

0 |

4 (30) |

0.004 |

|

Disease-free survival at 5 year (%) |

56 |

66 |

29 |

0.002 |

|

Overall survival at 5 year (%) |

77 |

86 |

51 |

0.019 |

|

*One patient had recurrence in bone and brain. |

||||

Table 1 CCRC vs. Non-CCRC results

|

Author |

N |

Prevalence (%) |

Mean age (year-old) |

Symptomatic n (%) |

Type of surgery |

CCRC n (%) |

OS |

||||

|

PD |

dP |

tPD |

cP |

TEn |

|

||||||

|

Hiotis et al. (2002) 7 |

16 |

N/S |

63 |

11 (69) |

8 |

7 |

1 |

- |

- |

10 (62) |

50% (3 years) |

|

Jarufe et al. (2005)23 |

13 |

N/S |

62 |

2 (85) |

7 |

2 |

4 |

- |

- |

7 (53) |

N/S |

|

Crippa et al. (2006)22 |

13 |

5 |

59 |

7 (54) |

7 |

4 |

- |

- |

- |

-45 |

48% (5 years) |

|

Reddy et al. (2008)6 |

49 |

1.3 |

60 |

45 (92) |

31 |

14 |

4 |

- |

- |

21 (42) |

N/S |

|

Mourra et al. (2010)19 |

12 |

N/S |

60 |

4 (33) |

4 |

8 |

- |

- |

- |

8 (66) |

N/S |

|

Untch et al.(2013)24 |

70 |

N/S |

N/S |

N/S |

20 |

44 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

27 (39) |

56% (5 years) |

|

Rubio et al. (2012) |

48 |

3.1 |

62 |

18 (38) |

12 |

26 |

5 |

1 |

4 |

35 (73) |

77% (5 years) |

Table 2 Literature review

PD, pancreatoduodenectomy; DP, Distal Pancreatectomy; TPD, total pancreatoduodenectomy; CP, central pancreatectomy; TEn, tumor enucleation; N/S, non-specified

Many publications have reported the possibility of developing metastases in the pancreas, and most of them are from CCRC. Only few publications reported PM from other tumors.6–8,14–21 Metastases should always be kept in mind in patients presenting with pancreatic masses with a history of another malignancy, especially tumors which are known to metastasize in the pancreas. The prevalence of PM is lower than 5%,1–4 being CCRC the most frequent origin.1,3,4,9,22–25 PM, like in our series appear during the long -term follow-up, reason why a close long-term monitoring is mandatory, in those patients for early detection, even after 10 years.

The way the primary tumor metastasizes in the pancreas is not fully understood; most of the reported pathological hypotheses focus on tumor angiogenesis as a main related factor. Huang et al.26 demonstrated that some microRNAs, especially mRNA-30a, have shown to be involved in tumour progression and metastasis in kidney and other cancers, being an independent predictor for CCRC hematogenous spread. Fox’s proteins have been described also as signalling pathways that might play a critical role in the pathological processes of renal cancer.27

Imaging studies, play a very important role in the diagnosis of PM. CT scan is the most used. In non-enhanced CT, most PM appeared hypodense compared to the normal pancreatic parenchyma. On T1-weighted MRI, the tumour is generally hypointense, on T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted, the PM appear as hyperintense lesions. The enhancement pattern may be helpful in lesion characterization, particularly in hyper-vascular lesions as CCRC, extra-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and medullary thyroid carcinomas. Smaller tumors enhance homogenously, and larger lesions show peripheral enhancement due to central necrosis, although this may not always be the case. Most other metastases are typically hypo-vascular. The late arterial capillary phase (also known as the pancreatic phase) provides maximal pancreatic parenchymal enhancement and is optimal for lesion detection.28,29 When analysing whether PM were more frequent when the primary tumour was in the right or left kidney, we found a statistically significant difference indicating that primary tumours of the right kidney metastasize more than those of the left kidney. To the best of our knowledge, there is no other publication that have analysed this issue in the international literature; however, studies with a greater number of cases are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Reddy et al.,6 report other aetiologies as causes of PM; in their series of 3830 patients who underwent pancreatic resection, 49 (1.3%) had PM, in their series the most common primary tumor reported has also been CCRC with similar demographics to our series (median age was 60 years, 55% were female, and 45 patients had symptoms at presentation). Untch et al.24 published 5-year survival of 56%, lower than our observed survival (77%) including all types of tumors. The reason of better survival might be related to a different in prevalence of tumor origin; (73% of CCRC in our series, vs 61% of non-CCRC) in the series published by Untch et al.24

Surgery has been proposed as the best therapeutic alternative for those patients.5,6,28,30 A total pancreatoduodenectomy should be indicated when multiple tumors are found. The total excision of the disease is the best oncological option but produces total endocrine and exocrine insufficiency; whose management evolved over the last 10 years, under multidisciplinary teams. In our series, morbidity and mortality after total pancreatectomy, were comparable to high volume centres in pancreatic surgery31,32 44% and 3.4% respectively. Vascular resections can be performed in order to achieve R0 resection; with comparable results to primary tumours (adenocarcinoma), when venous resections are necessary due to involvement of the porto-mesenteric axis.33–37

As we have reported, those patients with PM from CCRC had statically significant better disease-free survival and overall survival, compared with non-CCRC, in accordance with those reported by Reddy, et al.6 In that context, it is important to identify those patients who will be benefited with surgical approach. Most patients with non-CCRC PM, had a benign behaviour from the surgery of the primary tumour, up to the appearance of the PM, even if the PM appear during the first 5 years of follow-up. The type of primary tumour changes the type of adjuvant therapy indicated; but upon recurrence, there are no reports or consensus on the best oncological approach. Recurrence after pancreatic resection for a PM, has been mainly located in the bones (38%), and were treated with chemotherapy.

In conclusion, although PM has a low incidence, the appropriate diagnoses is required because CCRC PM had better long-term results than non-CCRC PM; when diagnosed, surgical resection remains as the preferred oncologic alternative, and adjuvant therapy, as well as closed follow-up must done under a multidisciplinary team.

None.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

©2022 n:, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.