MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6162

Mini Review Volume 6 Issue 1

Department of Visceral Surgery, Hassan II University Hospital, Morocco

Correspondence: M. Alila, Department of Visceral Surgery, Hassan II University Hospital, Morocco, Tel 212 662 632 625

Received: December 09, 2017 | Published: February 1, 2018

Citation: Alila M, Dkhissi Y, Merghich O, et al. Internal hernias: unusual causes of small bowel obstruction, about 11 cases. MOJ Surg. 2018;6(1):5-8. DOI: 10.15406/mojs.2018.06.00113

Internal hernias are rare and develop when one or more viscera protrude through an intraperitoneal orifice while remaining within the peritoneal cavity. The clinical diagnosis is always difficult and leads to an urgent operation for intestinal obstruction. The treatment is often simple and the results are generally excellent.1 In the literature, some case reports have been described, but rarely series.1,2 The aim of our study is to report 11 cases of internal hernia representing different anatomical types of the 11cases presently reported, the sex ratio showed a male prevalence with a mean age of 39years. Symptomatology was totally non specific and the preoperative diagnosis was possible only for tow cases by scan imaging.

All patients were explored urgently: 7 were hernias through a paranormal orifice (3 left and 2 right par duodenal, 1 intra-mesosigmoidal and 1 retrocecal), 4 were hernias through a pathologic orifice: 2 trans-mesenteric, 1 in the posterior cavity through a colo-omental dissinsertion hole and 1 trans-mental. Reduction of herniated viscera was simple, by gentle traction for nine patients, but requiring dilatation of the hernial orifice with resection of the ischemic small bowel in 2cases. So, internal hernias remain a rare cause of consultation on emergency. It must be evocated in patients with no medical history and consulting for acute intestinal obstruction. The CT scan suggests often the diagnosis that is confirmed at surgical exploration. The treatment is always surgery.

Keywords: internal hernia, acute intestinal obstruction, CT scan, laparoscopy

Internal hernia is defined as the protrusion of an abdominal organ through a peritoneal or mesenteric aperture. It is a rare cause of small bowel obstruction. The incidence of these hernias is estimated at between 0, 2 and 2% of abdominal hernias, and 0.2% to 0.9% of autopsies.1,2 It can be primitive or secondary to an abdominal intervention. Internal hernias are classified based on the location of the potential defect.3 The aim of our study is to report 11cases of primitive internal hernia, representing different anatomical types.

Eleven patients of a mean age of 39years (range 19-71) were admitted, on emergency, to our department of Visceral surgery, at HASSAN II university hospital of FEZ (Morocco), during a period of five years (from 2012 to 2016). We reported 7 males and 4 females. All patients denied any surgery or intra-abdominal inflammatory process. We reviewed the patient’s records, imaging modalities and operative findings of these cases. All patients were operated.

Incidence of these hernias in our series being 0.15% (11 of 7241cases) of laparotomies, 1,17%(11 of 935cases) of parietal hernias and 1,4% (11 of 790cases) of bowel obstruction. The sex ratio showed a male prevalence (7males/4 females), age distribution demonstrating the onset of internal hernias at all ages with a preference for the 4th decade and a mean age of 39years. All patients consulted on emergency. Table 1 shows the presenting symptoms of our patients. All patients were symptomatic: nine (81, 82%) presented a clinical picture of small bowel obstruction, two of peritonitis.

Other abdominal symptoms were found: abdominal pain (n=11), nausea (n=8), vomiting (n=9). The interval between the beginning of symptoms and hospitalization ranged from 24 to 72hours (mean: 48hours). The physical exam revealed abdominal distention in 6patients (54, 55%), abdominal tenderness in 2patients (18, 2%), and peritonitis in tow patients (18, 2%). Abdominal X-ray showed air fluid levels in nine patients (81, 82%). Ultra sonography examination showed peritoneal fluid in five patients. CT scan was done in seven patients on emergency. It suggested non specific internal herniation in five patients. In the other two patients, it suggested a specific internal herniation: a right parduodenal hernia in tow cases (Figure 1).

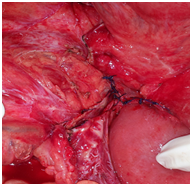

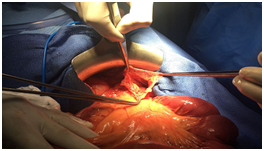

All the patients were explored urgently by midline incisions. The different types of hernia found were through: Paranormal orifice: 3 left paraduodenal (Figures 2) (Figure 3A) (Figure 3B), 2 right paraduodenal, 1 intra-mesosigmoidal and 1 retrocecal. Abnormal pathologic orifice: 2 trans-mesenteric (Figures 4A-4C), 1 in the posterior cavity through a colo-omental dissinsertion hole Figure 5 and 1 trans-omental. The Reduction of the herniated viscera was never a problem but a bowel necrosis was found in two cases, which required dilatation of the hernial orifice and resection of 1, 25m and 60cm of small bowel with immediate restoration of continuity. The closure of peritoneal fossae or an abnormal orifice was done easily with a resorbable suture (Table 2). We had no death in our patients. Two cases of wound infection were reported classified Grade I in the Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications. These patients were treated by antibiotics and had local treatment. The length of hospital stay was 8 days (3-11days). In the follow-up, there was no recurrence.

Figure 4C Closure of a trans mesenteric hernia’s orifice, after the resection of bowel necrosis and immediate restoration of continuity.

Figure 5 The orifice of a tran’s mesocolic hernia.

Internal abdominal hernias develop when one or more viscera extrude through an intraperitoneal orifice but remain within the peritoneal cavity. The orifice may be normal (Winslow's foramen) or paranormal (peritoneal fossae: paraduodenal, ileocecal, inter- mesosigmoidal, paracolic, and fossae of the large ligament of uterus). All these hernias possess a sac and are true hernias. The orifice may also be abnormal: pathologic origin if formed in a mesentery or an omentum (trans-mesenteric, trans-mesocoloic, trans-omental, by colo-omental disinsertion) or in the form of an anomalous orifice if it occurs in a congenital anomaly of a ligament (falciform ligament of liver) or a mesentery (mesentery of Meckel's diverticulum): all these hernias lack a sac and are "internal prolapses or procidentia.1,2"

Incidence of these hernias reported in the literature is between 0.2 and 0.9% of autopsies and 0.2 and 2% of parietal hernias, findings in our series being 0.15% (11 of 7241cases) of laparotomies and 1,17% (11 of 935cases) of parietal hernias. As traditionally described by Meyers4 and according to the literature on internal hernia of 1871cases described in the occident or near occident , 160(8.55%) were hernias through Winslow's foramen, 1035(55.31%) through a para-normal orifice (para-duodenal hernias are the most frequent, then the retrocecal, and only 5% of intra meso-sigmoidal or pararectal hernia). And 676(36.1%) through an abnormal orifice (pathologic and anomalous).1,2

Some series reporting that the primitive internal hernias have no sex predilection and the age distribution demonstrating the onset of internal hernias at all ages with a preference for the 5th decade and a mean age of 46years.1,5 But our series reflected a male prevalence with: 7males/4females. Clinically, it presents from intermittent and mild digestive complaints to acute intestinal obstruction. Sometimes, this condition may be silent if spontaneously or easily reducible. Majority often present with epigastric discomfort, periumbilical pain, and recurrent episodes of intestinal obstruction features eg. Nausea, vomitting, tenderness, abnormal bowel sounds, palpable mass. Internal hernias are clinically apparent only when strangulation +/- ischaemia results.1,5 Symptom severity relates to the duration and reducibility of the hernia and the presence or absence of incarceration and strangulation.5

Imaging studies often play an important role in the diagnosis of internal hernias because of the non specificity of clinical signs. CT is the first-line imaging technique in these patients because of its availability, speed, and multiplanar reformatting capabilities. CT could show the hernia sac and its anatomic relationship to the surrounding organs and vasculature. It can also find mesenteric vessel abnormalities, with engorgement, crowding, twisting, and stretching of these vessels commonly found and providing an important clue to the underlying diagnosis.6–8 In our series, it showed no specific signs suggesting internal hernia in five cases, but in the other two cases, it confirmed the exact type of the hernia.

The treatment of these herniations depends on the surgical findings. In the absence of necrosis, it consists of a reduction of the hernia, with closure of the defect when it is possible. The reduction of the hernia is generally not a problem, except through the foramen of Winslow where the reduction must be bimanual and atraumatic,9,10 Closure of a sac is easy when one is present, or closure of an abnormal or paranormal orifice; a problem one may face is, what to do with a normal orifice such as the foramen of Winslow : most authors don't close it because of the risk of portal vein thrombosis,1,9 perhaps the greater omentum should be used. This procedure can be done, depending of the patients and the experience of the surgeon, by laparoscopy or laparotomy.3,5 Approximately 50% of the patients developed morbidity after surgical procedures. Age, delayed laparotomy time (>3days after the onset of the symptoms) and the presence of a comorbidity were related to morbidity.9–11

An internal hernia remains a rare condition, pre operative diagnosis is practically impossible. In the presence of intestinal obstruction or peritonitis, an urgent surgical intervention is the rule, preferably through a midline incision to allow a thorough inspection of the abdominal cavity. While treatment is often uncomplicated, the foramen of Winslow remains problematic. In the absence of peritonitis, results have been excellent and without a recurrence.

Mohammed Alila, wrote the paper and gathered referenced data Yassin Dkhissi, Omar Marghich gathered referenced data, contributed equally in organizing them, and took the photos K. Ibn Majdoub Hassani, H. Elbouhaddouti, O. Mouaqit, A. Ousadden, K. Ait-Taleb, participated in the follow up. E. Benjelloun reviewed the final paper.

Authors declare there is no Conflict of interest towards this manuscript.

©2018 Alila, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.